Nicholas Doumanis is currently Associate Professor of History at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. He is a recipient of the Stanley J. Seeger Fellowship at Princeton University and was awarded the Fraenkel Prize in Contemporary European History for Myth and Memory in the Mediterranean. He has written several books on Greece, Italy, the Ottoman Empire and the Greek diaspora, among them, Italy, Inventing the Nation (translated into Italian as Una Facia Una Razza), A History of Greece and Before the Nation: Muslim-Christian Coexistence and its Destruction in Late-Ottoman Anatolia. He is currently writing a book on the the Eastern Mediterranean for the Wiley Blackwell History of the World series. After teaching for 22 years at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, he will be Hellenic Foundation Chair of Hellenic Studies and Professor of History at the University of Illinois Chicago.

On the occasion of the publication of the book The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, 20th and Early 21st Centuries: Global Perspectives, co-authored with Professor Antonis Liakos, Nicholas Doumanis spoke to Rethinking Greece* on how his diasporic identity has shaped his perspective as a historian, the significance of global -and local- factors in the shaping of Greek history, why a small country on Europe’s periphery has so often been in the forefront of global historical developments, the way diasporic communities (or as he calls it, a “transnational Greece”) continue to live on, the way Greeks and southern Europeans understand Europe, and finally, on Greece’s perspectives at the end of this “long Greek 20th century”.

You were born in Australia to Greek parents. Did your identity as a Greek-Australian and your experience growing up in Australia, a multicultural society par excellence, shape the way you approach modern Greek history?

Growing up in the diaspora has been critical to my development as an historian. It was the fact that I was Greek at home and Australian outside of home. Every day I moved between two worlds. Each world had different social rules and a different language. And yet I and my generation of Greek Australians were never full members of the Greek world or the Australian world. Our parents were a different species. They lived, thought and acted differently. They had been conditioned by Greece and Cyprus of the 1940s, 50s and 60s. My generation was conditioned by the Australian education system, the workplace and public life in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Australians looked at us as outsiders and were often unwelcoming.

But there were benefits to being half inside and half outside. You notice differences and then, if you happen to be interested in history, anthropology or comedy, you might try to explain the differences. But not many are interested, even historians! The modern Greek diaspora has not attracted much attention from scholars. There is a curious assumption that only Greece is a legitimate historical subject and the diaspora is seen as not very interesting. This has partly to do with the fact that historians have been trained to read the past through national frameworks, and partly because diasporas eventually disappear. Yet if you read all periods of Greek history, you will find that migration is an intimate feature of it.

Finally, my education as an historian prepared me for the way I approach Greece. In the United States, Canada, Britain and Australia history students usually enrol in courses that are not about their own country. In Australia, most students do not study Australian history. I didn’t study either Australian or modern Greek history. I took courses mainly in European history, but when I became an academic in the 1990s, I wanted to know the general meaning of all these different histories. I was greatly influenced by historians like Fernand Braudel, who looked at history within bigger timescale and spaces, and I became an early disciple of global history. When I became a teacher at universities I taught courses in global history, and then I began to think how that might affect our understanding of Greece.

Obviously, Antonis (Liakos, the volume’s co-author) wrote as a Greek ‘insider’, but the reason why we worked very well together is that he has always been very interested in international and global historiographical developments. His work has always been transnational in nature, and very historiographically informed.

Τhe Edinburgh History of the Greeks as a series aims to examine Greek history in the context of global change and international relationships. How is that goal implemented in the current volume on the 20th and 21st centuries?

You must begin with the big picture. The twentieth century witnessed accelerating change. In previous centuries change was slow and barely noticed. The average Greek in 1890 still lived in a premodern village, and he or she was not very different to a Greek in 1750 or 1250. But after 1890, each generation was different to the one before. There was no ‘normal’. But what I just said applied to many peoples and cultures. The whole world was changing together. Greece was caught up in these global changes, but the changes were led by powerful centres like northwestern Europe and the United States.

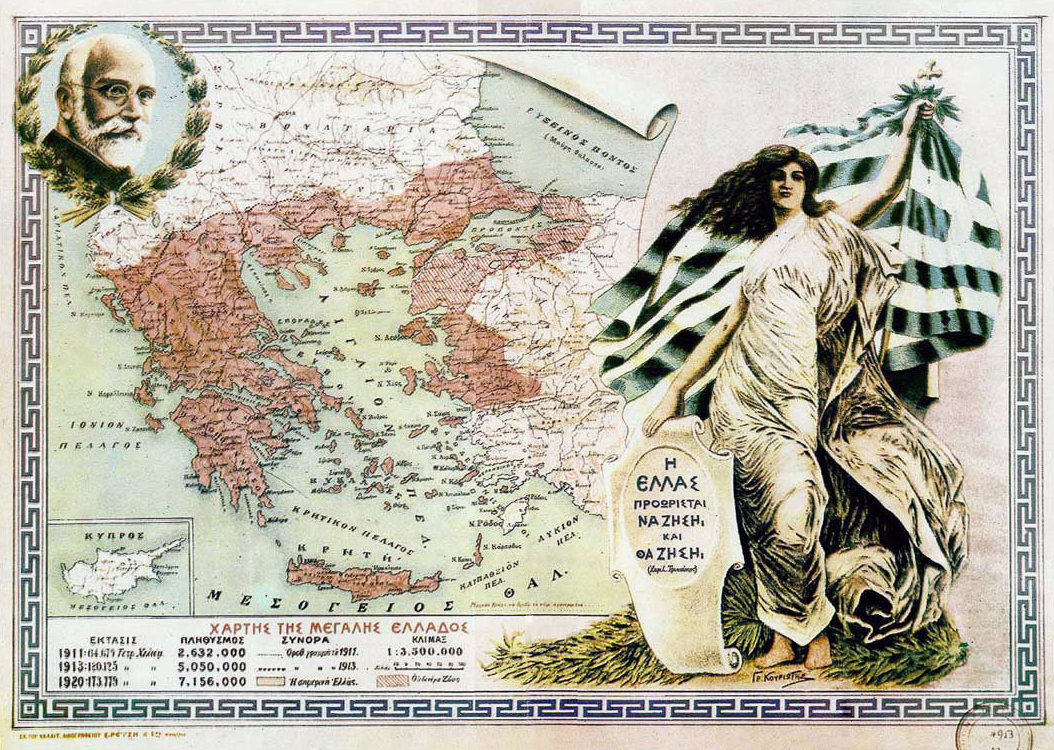

Greece was always forced to respond to international political changes as well. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Greece was located on the fault lines between empires. It tried to manipulate these fault lines to achieve its ‘Megali Idea’, but these fault lines usually presented problems. In 1940 Greece was forced into a war for which it was not responsible, but which turned every Greek life upside down. In 2008 the Greek political elite revealed that the country was left fully exposed on a global financial fault line, and then Greek society was left to pay the bill.

It is important to the writer of any national history to read global history books too. I am greatly influenced by such works as Christopher Bayly’s brilliant Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914 (2006), and the books of William H. McNeill, Eric Hobsbawm, and Charles Maier, is very important. To understand Greece in recent years it is obvious one must know something about the global financial crisis, and the most important influence on me was Adam Tooze’s Crashed (2018), especially because he recognises Greece and its place within that crisis.

In this volume Antonis and I tried to establish the significance of global factors, but we also considered the local factors, and the agency of the Greek people, including Greek women, youths, minorities etc. Greeks often did things in particular ways, as exemplified by the plebiscite of 2015, which much of the world found very confusing.

Geography has always played a big role placing Greece and Cyprus in the middle of international problems. Imagine if Cyprus was closer to Rhodes than to Syria? What if Greece swapped its location with Portugal? Cyprus would have had a history more like that of Crete. Greek history and Portuguese history would be very different.

Consider the First World War. Because of its geographical position, Greece was not permitted to be neutral. It was Greece’s location in the eastern Mediterranean that made it Europe’s Cold War front line in 1945. And yet because of geography, Greece was also a bit too hard to control. The Germans and their allies could not bring it under their control. The Allies had the power to stabilize western Europe in 1944-1946, but not enough to control and stabilize a country like Greece (or Yugoslavia). Therefore, Greece was the only part of Europe that could become a military battleground of the Cold War.

Greece’s central role in the Global Financial Crisis was just bad luck. In the book we explain the domestic origins of the Greek economic crisis, but the idea that Greece’s financial instability could bring the global economy crashing down said a lot more about the structural problems of the international financial system. That Greece should have been the focus of the Eurozone crisis said a lot more about Eurozone’s internal political and structural issues.

Despite being a small country, and a minor economy, it has managed to draw more attention than most of its neighbours. This has partly to do with the role ascribed to Ancient Greece in the Western Tradition, as the USA and Europe see Greece as its ancestral home. Countries of a similar size, like Romania, Bulgaria, Finland or the Czech Republic have lower recognition. In the book Antonis and I talk about Greece as a ‘brand’ and that people generally recognise Greece for its culture and beaches. The Greek diaspora has also played a role in drawing international attention to Greece, as we saw with the Greek Revolution of 1821. The Greek American diaspora almost produced two presidents, Agnew and Doukakis. Greece is a brand.

The 20th century history of Greek diaspora reflects the global transition from multi-ethnic empires to nation-states, as well as the waves of economic migration. Do you believe that we can still talk of a Greek “Oikoumene,” in the sense of a transnational Greek world?

Yes, there is a transnational Greek world today, but it is changing. First generation Greek immigrants consciously created a Greek world that was framed by ‘spaces’, such as ‘Greektowns’, church parishes, brotherhoods, Greek language newspapers, Greek shops (sweetshops, delicatessens, cafes) and neighbourhoods. They created structures to build a new Hellenic world. When this generation of immigrants got old and moved to the suburbs, the neighbourhoods disappeared, their brotherhoods declined in membership, and the newspapers found fewer and fewer readers.

But the diasporic communities continue in a more organic fashion. Greeks still like to marry other Greeks, they maintain Greek friendships, they observe the Greek holidays, weddings, baptisms, etc. Most of the children of first generation immigrants are emotionally tied to Greece, and many of them hold senior positions in government and major institutions. Most of the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Greek emigres do not speak fluent Greek or enrol in Greek language classes, but a huge number like to go to Greece, listen to modern Greek music, and feel a strong connection to their ancestral country. If you attend a Greek wedding in Sydney today you will see that this generation knows and loves its Greek dances, and they all seem to know some recent songs, like Paschalis Terzis’ “Δεν θέλω τέτοιους φίλους.” Therefore, there is a big diaspora that still seeks its connections with Greece.

Remember too that the diaspora has also received a recent wave of immigrants caused by the Crisis. Some of them are sadly part of the brain drain, but many are also just young Greeks and in need of work, often with passports as they are the children of returned migrants. Naturally this new emigrant wave has strong ties to the homeland and usually mixes with other emigres socially. The question is whether they stay or go back. And if they stay, how did they connect with other Greeks.

Historians are not good at predicting the future. Unexpected contingencies like the September 11 attacks, the Bush Administration’s decision to invade Iraq, Covid-19 and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, pushed international politics and global conditions along unexpected pathways. In 2009 I finished a different book on the history of Greece from ancient times to the present, and I made a very positive prognostication. By the time the book appeared I knew I was very wrong, but the reviewers seemed to understand. My excuse is that I didn’t fully grasp the implications of the Global Financial Crisis for Greece and did not expect the EU’s punitive approach to the Greek situation. I am hoping to revise the chapter one day.

All historians can do is predict possible futures. Comparisons between the present and the 1920s and 1930s, when we also saw a rise in populism and an apparent willingness of citizens to support authoritarian rule, are extremely illuminating. But the evidence so far is that Greek society has resisted that path, perhaps because many still remember the Junta, and what happened in 1973 and in 1974.

Greece is a success in some important senses. Democracy has so far survived the Crisis. Women have more choices and much greater freedoms than their mothers and grandmothers had. Greeks no longer live in fear of political repression as they did for much of the twentieth century. But economically the outlook is less optimistic. The austerities have not worked in the short term. They still seem to be a form of punishment rather than measures that will prepare the country for growth. Will the changes imposed by the EU and creditors provide a form of ‘creative destruction’ (i.e. the removal impediments to progress)?

What I do know as a student of history is that Greeks are resilient and resourceful. They have always had to be mobile. They have always had to work with less.

TAGS: MODERN GREEK HISTORY