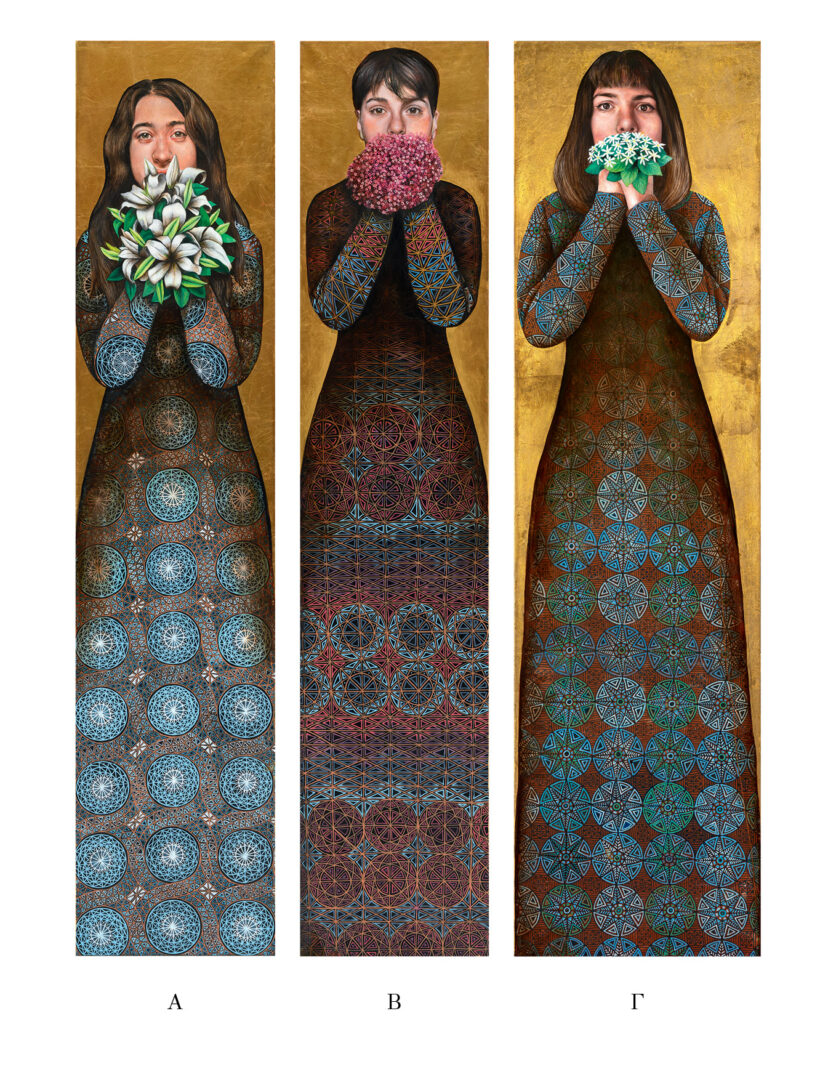

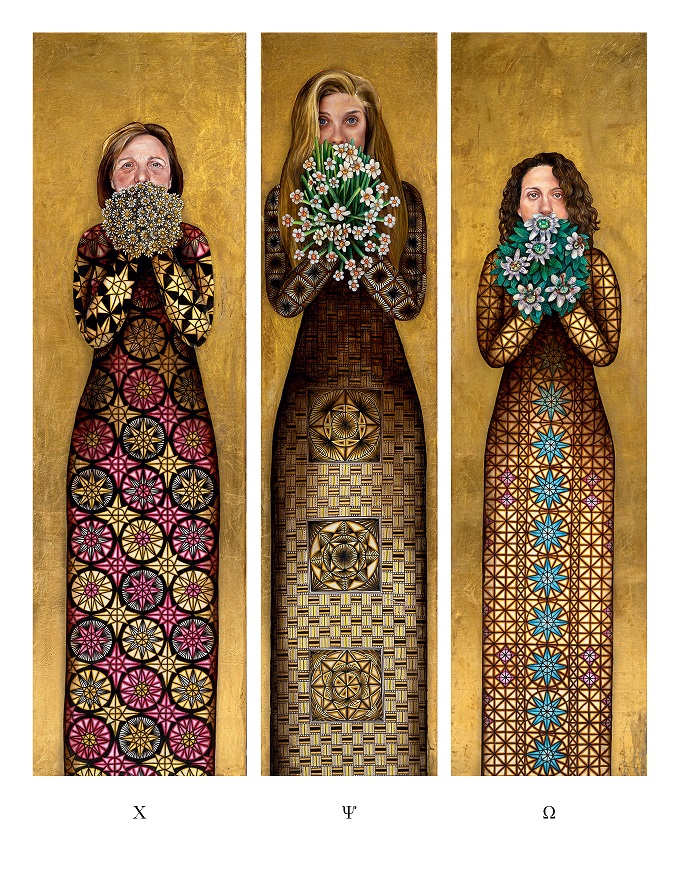

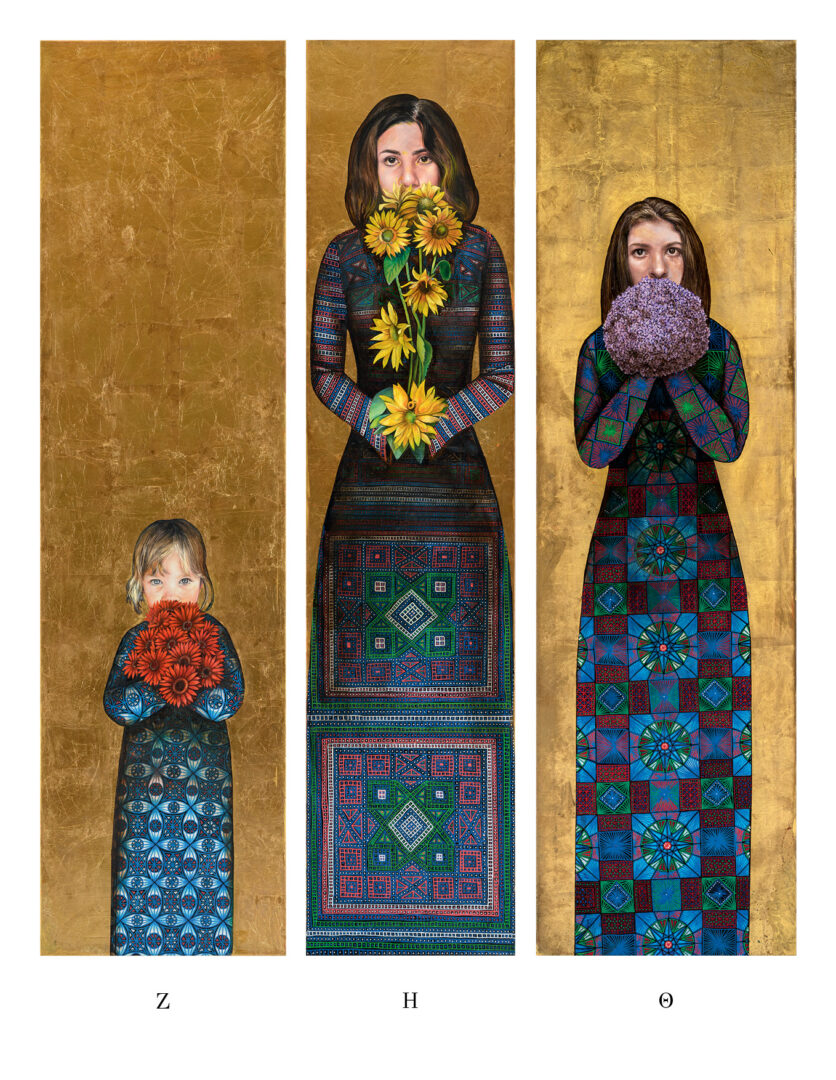

Elena Papadimitriou’s art unfolds as a tapestry of symbolic and mystical elements, depicting life as a collage of beauty and inner pain. Through her mysterious, silent women, she highlights the role of women in today’s society, a society that expects them to fit into roles dictated by the past. Although her figures appear dynamic and captivating, their mouths are sealed with flowers (violets, roses, jasmine, rosemary, thyme, chamomile, dahlia, lavender, hibiscus). Their penetrating gaze tells stories and carries memories and pain. Trapped in their otherworldly reality, they do not dare to speak the truth about their lives.

Papadimitriou uses a metaphysical and fragmentary narrative structure to create a powerful visual aesthetic experience. Her latest exhibition, Bouche Fermée, alludes to a choral music term that refers to a technique used by choristers to produce a soft sound with their mouths closed. This technique creates an ethereal and gentle sound. Elena Papadimitriou transforms this musical term into a powerful visual experience, depicting 24 female figures essentially deprived of their voices.

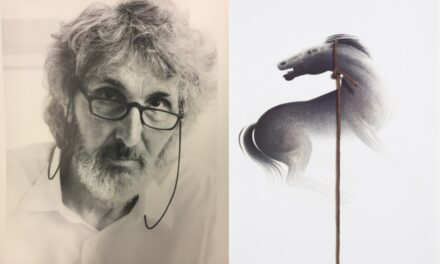

Elena Papadimitriou was born in Athens. She studied painting at the Vakalo School of Applied Arts, the Athens School of Fine Arts under professors Panayiotis Tetsis and Chronis Botsoglou, and at the Facultat de Belles Arts, Universitat Politècnica (Valencia, Spain). She has held six solo exhibitions and has participated in international fairs and several group exhibitions in Greece and abroad. Her works are part of prestigious private collections. She has also worked in advertising and has worked as a scenic designer for theatrical productions.

Elena Papadimitriou talks to Greek News Agenda * about her psychoanalytic approach to art, her sources of inspiration, and the role of symbols in her paintings.

The female figure has always been central in your paintings. How do you approach women in your art?

In my art, I approach women as if I paint different sides of myself. I see painting as psychoanalysis; a dialogue with myself and potential versions of myself. To paint is to write about life. And life includes current affairs, as well as all the social and political issues. In that sense, my art is a dialogue with myself on the issues that are important to me at any given time.

What are the issues that concern you as a visual artist?

I am interested in many and diverse issues. In the past, I used to be concerned with more personal situations. The ‘I’ in relation to my surroundings. My first exhibitions had a rather internal, more psychoanalytical approach. Lately, my themes are more social, seen always from my own perspective. In my previous exhibition, I focused on migration and the role of women in it. The idea was triggered by the huge migration flow, but I tried to give a more timeless interpretation.

My current exhibition focuses on the oppression of the modern woman. Gender equality, albeit institutionally established, is still far from reality, especially outside the Western world. The #MeToo movement and the rise in gender-based violence were the reason for this exhibition. Perhaps I finally realized that the problem is not me, but the society, and I find it interesting to focus more on it.

Women in your works appear silent and introverted. How do you perceive their position in Greek society?

I am not aware of all the reasons that even today, women are still trapped in roles and perceptions of the past. Certainly, religion plays an important role and in our country, it remains strong. So are close family ties. In Greece, we never really cut the cord. The family is supportive but, at the same time, oppressive. The economic crisis has forced many people to remain within the family, and therefore trapped in outdated perceptions.

Could you tell us more about the motifs you use in your works, especially in the costumes of the women depicted?

I often use patterns to tell a story; they function as symbolic elements that add depth and narrative to the work. In particular, I draw inspiration from motifs that carry memories, social or cultural references. Through textures, colors and details, I attempt to explore the entrapment of women in a society that expects too much from them. Furthermore, the contrast with the static nature of their bodies reinforces the dimension of an inner conflict.

What is the role of reflections in your art?

This has been an issue of concern for me for many years. Me and the others. My figures are trapped in their rigid outline, while the rest of the world, as a reflection, lays outside. At the time, I was strongly concerned with loneliness, isolation and alienation. Later on, I focused more on social issues. However, the idea of the human figure within his closed outline is still very much alive in my work.

You often use symbols in your works. Tell us about them and, in particular, about the flowers that play a central role in your latest exhibition.

I love hidden messages. I like to hide symbols in the works and give them multiple readings. In my current exhibition, I used flowers to close the mouths of the women I depicted. In Victorian England, the exchange of floral arrangements was a code of communication known as floriography. Flowers had symbolic meanings and could carry secret messages, especially at a time when social rules prevented the direct expression of emotions. When I was once given a book on the subject, I found especially intriguing the idea of my women being silenced behind flowers that concealed a reason for oppression.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi

TAGS: ARTS