In the framework of the initiative “Exhibits of the Month”, the National Archaeological Museum presents in 2025 the cycle “Priests, Rituals, and Magic in Antiquity”. Twelve “biographies” of objects from the permanent exhibitions of the Museum’s Collections, one on the 25th of each month, are presented to the Museum’s online followers and invite them to come and see these objects up close in the Museum.

Man’s anguish to explain the world around him, his desire to appease nature and to become familiar with death, has been an integral part of his existence. Over the centuries, the boundaries between rationality and superstition have often become blurred, while a complex network of gods and demons have enriched the art and mythology of all cultures, ultimately demonstrating their worldview. Representations of deities, priests and rituals unknown to us, have been preserved in wall paintings, votive sculptures and figurines. (Source: National Archaeological Museum)

Neolithic clay figurine from the Neolithic settlement of Sesklo in Magnesia, Thessaly, Early Neolithic (6500-5800 BC), height 6,5 cm, Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities, National Archaeological Museum

A peculiar clay figurine of a «centaur» from the Neolithic settlement of Sesklo, 15 km SW of the city of Volos, at the foothills of Mt Pelion seems to reveal a supernatural aspect to the perception the Neolithic inhabitants of Thessaly had of the world. Among the clay Neolithic figurines from that area, the homeland of the Centaurs in historical times, this non-natural being, stands out.

The prehistoric settlement of Sesklo, located on Kastraki hill, spans an area of 100,000 m², encompassing both the hill and the surrounding plain. It was initially excavated by Chr. Tsountas in 1901-1902. The settlement was occupied from the 7th millennium BCE. In the Early Neolithic, houses with stone foundations and mud-brick walls were built. The Sesklo culture emerged in the Middle Neolithic, known for advanced pottery firing techniques. It grew but was abandoned by the end of the 6th millennium BCE, then was reoccupied in the Late Neolithic, but only on Kastraki hill. (Source: odap.gr)

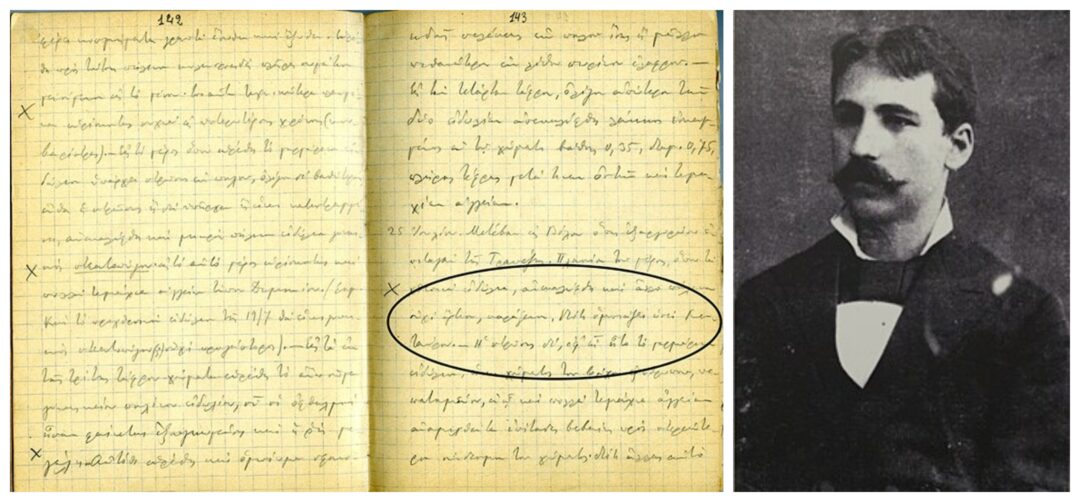

The characterization «centaur» of the clay figurine was assigned by the excavator himself, Christos Tsountas, in the excavation notebook and further discussed in the publication, where the figurine is illustrated in drawing. It depicts a figure whose upper body is human -probably male- and the lower one that of a four-legged animal, not though of a horse, as in historical times. After all, no bones of equines have been identified in Neolithic Thessaly. The hybrid form of the «centaur» magically combines the human with the animal force of Nature, necessary for long-term survival, but also an opponent to be reckoned with, probably of apotropaic character, as well. (Source: National Archaeological Museum)

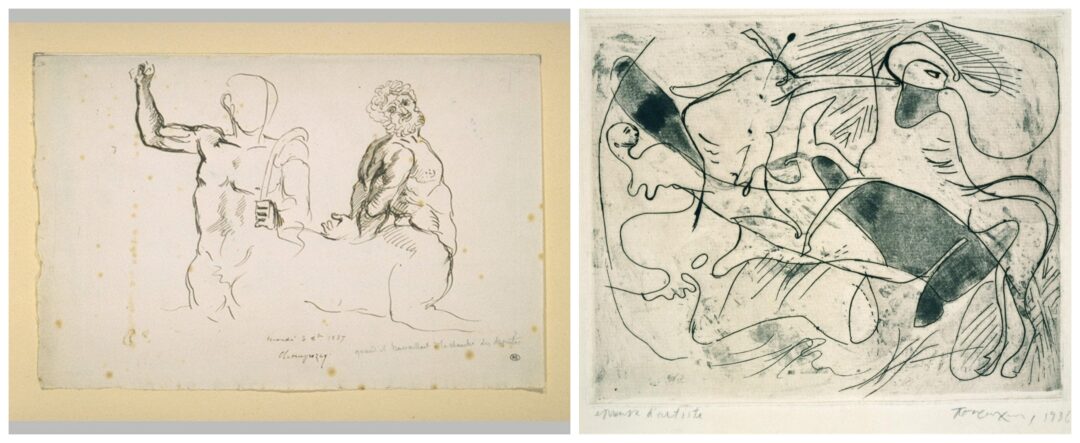

Christos Tsountas’ Sesklo excavation notebook (25.7.1901) with reference to the unearthing of the “centaur” figurine, HNAM Archive (left), Christos Tsountas photographed in 1879 (right). Christos Tsountas (Stenimachos, Thrace, 1857– Thessaloniki, 1934) is considered a pioneer of Greek archaeology and has been called “the first and most eminent Greek prehistorian”. He conducted the first archaeological survey of Thessaly, excavated several Mycenaean tombs in Laconia, and led the first formal excavations of the citadel of Mycenae. In the late 1890s, with his discoveries in the Cyclades he coined the term of Cycladic culture. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christos_Tsountas)

Clay statuette of seated male figure, known as the “Thinker”, from the district of Karditsa, Thessaly, Late Neolithic (4500-3300 BC), National Archaeological Museum (left), Neolithic clay figurines of seated on stool male figures with the hands on the thighs, from Sesklo Magnesia (middle), and Pyrasos Magnesia (right), Archaeological Museum of Volos (Source: National Archaeological Museum)

The “centaur” figurine resembles those of seated on stools, usually male, figures with the hands on the thighs, from Thessaly, in which the human legs merge completely with the front legs of the stool. A stronger resemblance appears in the cases where the back legs of the stool, instead of straight, are arched. However, there are certain differences: in the human figures, seated on stool, the body is clearly delineated from the seat and the four legs are equal in height.

The village societies of Thessaly have left behind a large variety of miniature human figure representations. The emphasis on the features of the human body that relate to fertility (pregnancy, breast-feeding, phallic symbols) indicates the primary purpose of society, its survival and proliferation, to overcome, among other things, the physical dangers and limitations. In this effort, supernatural and magical powers are evidently mobilized, judging from the hybrid creatures depicted on figurines. (Source: National Archaeological Museum)

Bronze Centaur figurine, 550-525 BC, Height: 6.8 cm, Length: 6.5 cm, Acropolis of Athens, Metalwork Collection, National Archaeological Museum – “…that monstrous host of double form, man joined to steed, a race with whom none may commune, violent, lawless, of surpassing might…” Sophocles, Trachiniae, lines 1095-1096 (http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/trachinae.pl.txt)

The Centaurs, half human, half horse, are among the strangest creatures created by the ancient Greek imagination. From the union of the king of the Lapiths Ixion with Nefele, a cloud made into the likeness of Hera, the first Centaur was born. The latter mated with the mares of Mount Pelion and so emerged the tribe of Centaurs. Most of them lived in the forests of Pelion; they were unrestrained like the forces of nature, aggressive, ready for riots and quarrels. On the other hand, there were bright exceptions among the Centaurs, such as Chiron who was a connoisseur of the healing properties of the plants, an excellent hunter, as well as a healer and a teacher of gods and heroes. With their image and their actions the Centaurs symbolize the duality of human nature and reveal the lower instincts that coexist with the high spiritual values of the human beings. (Source: National Archaeological Museum)

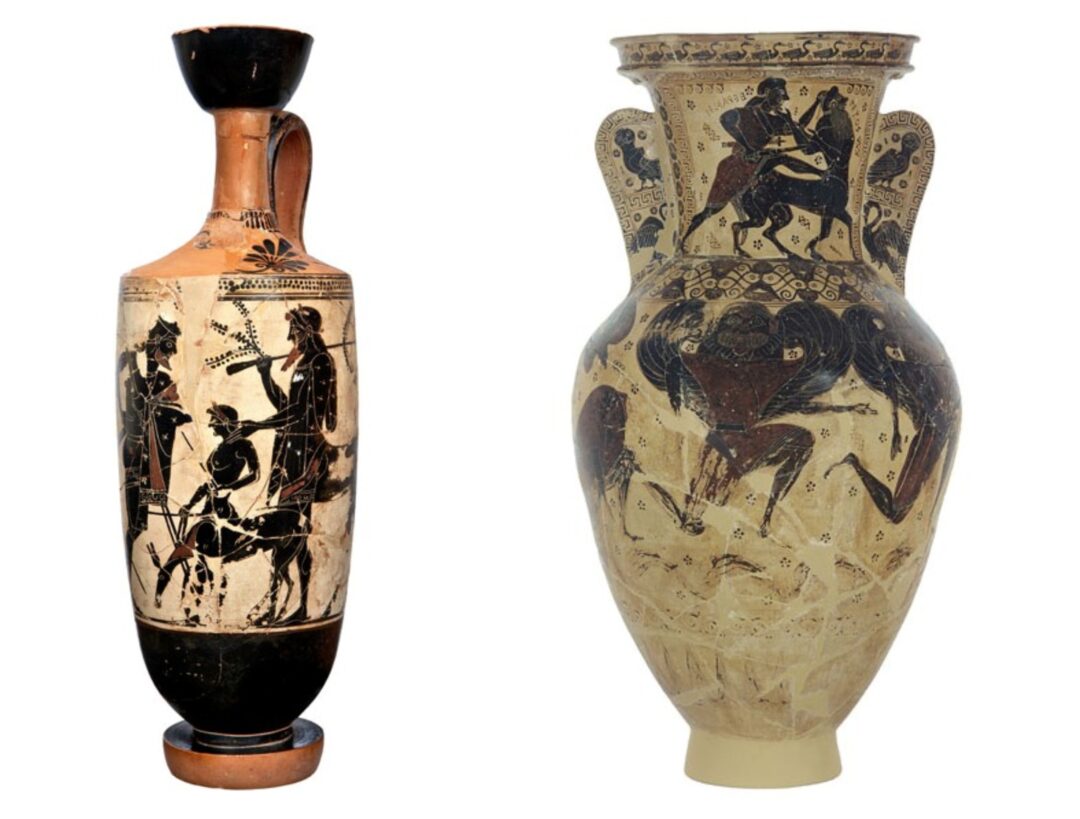

White-ground lekythos by the Edinburgh Painter, ca 500 BC. Black-figure representation: Peleus delivers Achilles to Centaur Chiron (left), Attic black-figure burial amphora by the Nessos Painter, 620-612 BC. Portrayed on the neck is the fight of Heracles against Centaur Nessos and on the belly the pursuit of Perseus by the Gorgons, headless Medusa’s sisters. From a grave at Peiraios St., Athens (right). Vase Collection, National Archaeological Museum.

Depictions of centaurs on ancient Greek pottery and architectural sculptures often show them in violent struggles with humans in the Centauromachy scenes. Centauromachy reflects man’s struggle against the wild elements of nature and his personal fight to maintain moderation and sense. In a different context, it symbolizes the conflict of the civilized Greeks against the barbarians.

Parthenon Metope 1, A Centaur grips a Lapith by the neck while he prepares to strike him a hard blow with a tree branch, Pheidias Workshop, 445-440 BC (left), Marble from Penteli, Height: 1.345 m Length: 1.305 m (left), Parthenon Metope 12, A Centaur grabs a Lapith woman and draws her forcibly towards him, Pheidias Workshop, 445-440 BC (right), Marble from Penteli, Height: 1.08 m Length: 1.22 m Width: 0.15 m, The Parthenon Gallery, Acropolis Museum.

The main theme of the 32 metopes on the south side of the Parthenon is the Centauromachy, the mythical battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs. The Centaurs, while attending the wedding feast of king Peirithoos in Thessaly, close friend of the Athenian hero Theseus, became drunk and attempted to carry off the Lapith women. The Acropolis Museum houses metopes 1 and 12 as well as fragments of 9 further metopes, which were found scattered on the Acropolis and the surrounding area. Their reconstruction was achieved with the help of the drawings attributed to the painter Jacques Carrey, who visited Athens in 1674, just thirteen years before its bombardment by Morosini. 15 out of the 18 best preserved metopes were forcibly detached by Thomas Bruce, lord of Elgin, when Greece was under Ottoman occupation, and ended up in the British Museum in London (nrs. 2-9 and 26-32). Smaller fragments have been dispersed in other museums abroad.

West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470-456 BCE, parian marble, pentelic marble, length: 26,39 m (pediment length), height: 3,47 m (maximum). According to the myth, the god of Light and Reaso, Apollo (at the centre) determines the outcome of the dramatic engagement between Lapiths and Centaurs. Archaeological Museum of Olympia (Photo: visit-olympia.gr)

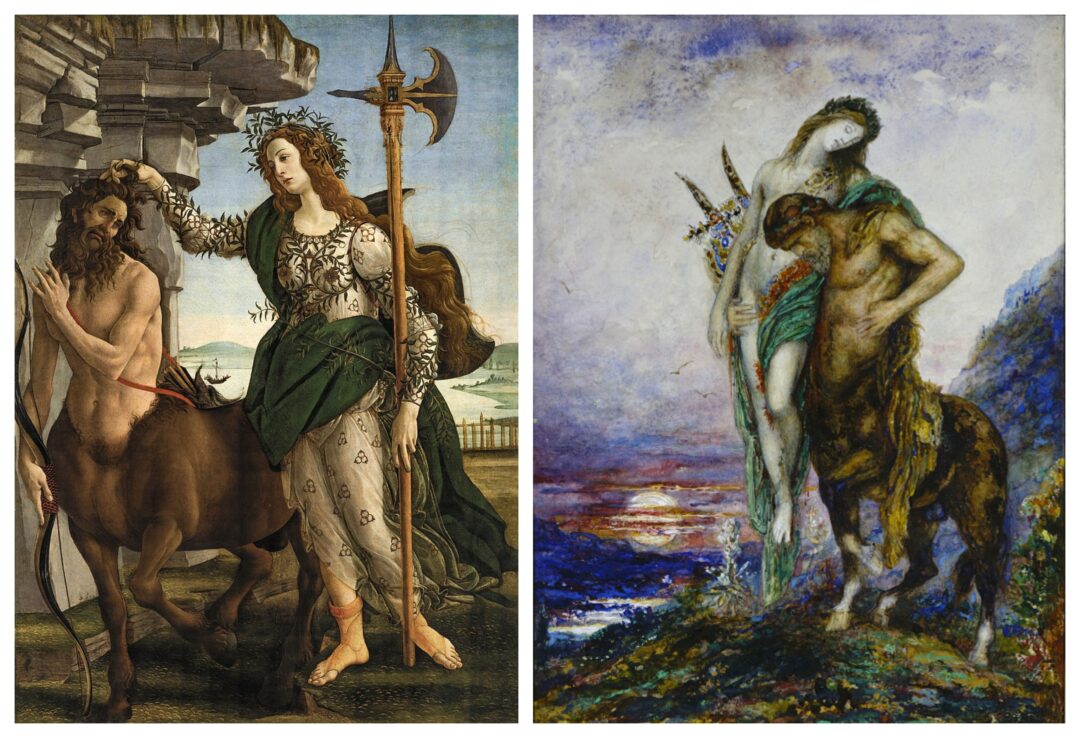

During the Renaissance, artists like Sandro Botticelli, who was influenced by the Neoplatonists, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci depicted centaurs in a more refined and intellectual manner, representing them in a more balanced and heroic light, reflecting the era’s fascination with human potential and mythological symbolism.

The depiction of centaurs remained popular in art throughout the centuries and centaurs continue to be influential to the present day as representations of primal human instincts and the ongoing human endeavor to balance these impulses with societal norms.

Sandro Botticelli, Pallas and the Centaur, 1482, Tempera on canvas, 204 × 147.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Pallas/Minerva is a major deity, representing wisdom, trade, and more. Centaurs are associated with uncontrolled passion, lust and sensuality. The painting’s meaning is clearly at least in part about the submission of passion to chastity and/or reason (left), Gustave Moreau, Dead poet borne by centaur, c.1890, gouache, watercolor, paper, Musée National Gustave Moreau, Paris. This painting by Gustave Moreau was made when Alexandrine Dureux, his best friend died (right)

Eugène Delacroix, Deux études de centaures, 1837, H. 0,2 m ; L. 0,299 m, encre brune à la plume, The Louvre Museum (left), Yannis Tsarouchis (1910 – 1989), Centaurs and Lapiths, 1936, Copperplate engraving (proof), 14 x 18,7 cm, Athens National Gallery (right)

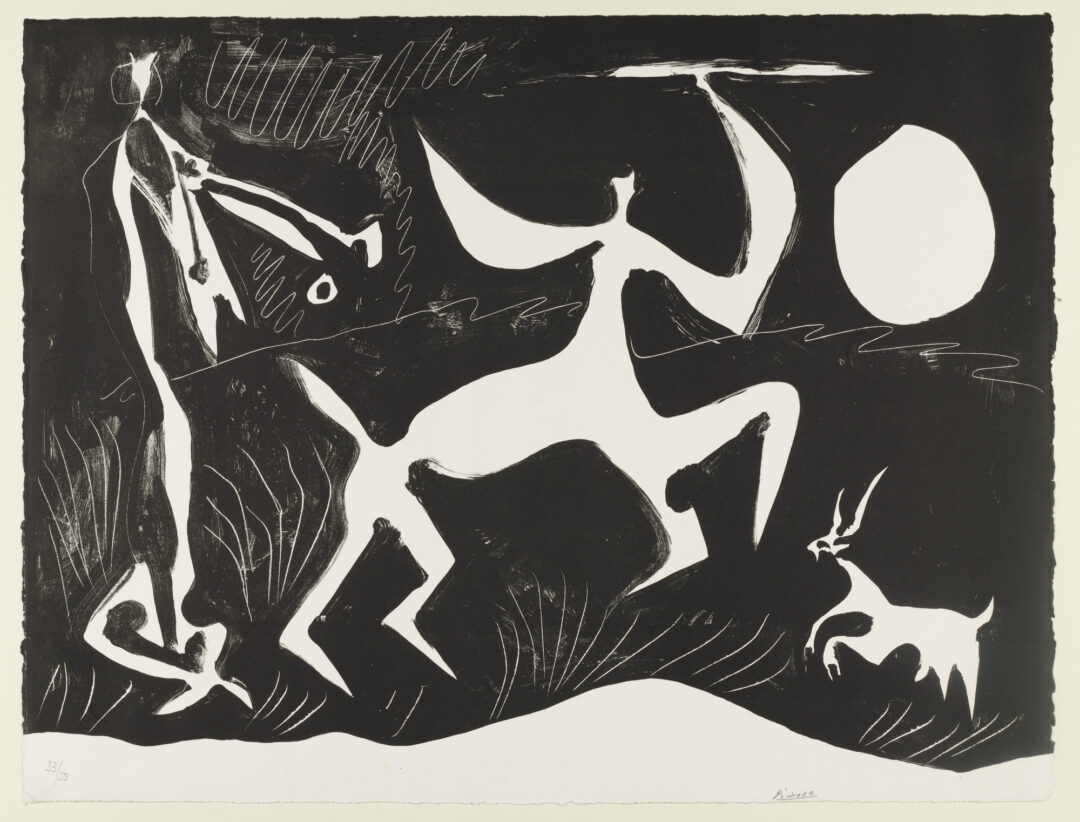

Pablo Picasso, Centaur Dancing, Black Background (Centaure dansant. Fond noir), 1948, Lithograph, 49.7 x 65.1 cm, Mourlot, Paris, © 2025 Estate of Pablo Picasso, MOMA

Also read:

Discover Foloi | The forest of the mythical Centaurs

The industrial and cultural heritage of the city of Volos

Exhibition: “Picasso and Antiquity”

I.A.

TAGS: ARCHAEOLOGY | CENTAUR | NEOLITHIC | THESSALY