Kevin Featherstone is Eleftherios Venizelos Professor of Contemporary Greek Studies and Professor of European Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is currently the Head of the European Institute and was long-term Director of the Hellenic Observatory –internationally recognised as one of the premier research centres on contemporary Greece and Cyprus- and Co-Chair of LSEE-Research on South-East Europe within the European Institute.

In 2009-10 he served on an advisory committee to Prime Minister George Papandreou for the reform of the Greek government. He was the first foreign member of the National Council for Research and Technology (ESET) in Greece, serving from 2010-2013. In 2013 he was made ‘Commander: Order of the Phoenix’ by the President of the Hellenic Republic. His research has focused on the politics of the European Union and the politics of contemporary Greece; his work has been framed in the perspectives of comparative politics, public policy and political economy. On Greece, he has co-authored or edited books on divese themes such as political change after 1974; Greece after the Cold War; Greece and the challenges of ‘Europeanisation’; a history of the Muslim/Turkish minority in Western Thrace; and the prime ministers of the post-1974 period (arguing that there is a paradox between their formal position and the informal constraints on the centre of government).

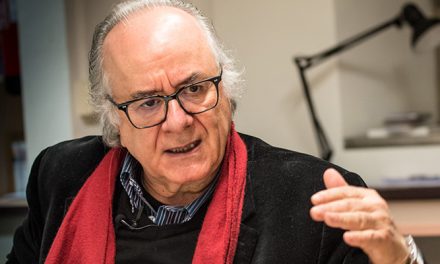

We spoke* to professor Featherstone, about the role of the Hellenic Observatory as a research hub for contemporary Greece and Cyprus, its contribution in the debate on Greece, the plans for its future, as well as on his perspective on the debt crisis and recent developments in Greece and the EU, the european economy, the refugee crisis and of course, ‘Brexit’. The professor stressed that the “the biggest current challenge is the lack of ‘burden-sharing’ between EU states and the limited ‘reach’ of EU governance at the domestic level. A ‘union’ needs burden-sharing across many fields, economics, migration, security, etc. A ‘union’ cannot be built on leaving another state to solve the problem.”

The Hellenic Observatory was established at the LSE in 1996 aiming to promote the multidisciplinary study of contemporary Greek politics, economy and society. In your opinion, what are its major achievements? What kind of difficulties has it faced in fulfilling its aims?

The main achievement, I think, is to create a major focus outside Greece or Cyprus for the study of the countries’ economy, society and politics. We are a platform that offers different audiences knowledge and information about their contemporary situation and we’re a hub that brings people together – academics, public figures, business leaders, journalists and the diaspora. We try to place Greece and Cyprus in a broader, international setting so as to attract wider attention.

As such, we’re ecumenical with regard to issues and opinions. We’re a neutral stage, on which to have serious and informed debate.

We have received much help and support, so our ‘difficulties’ should be seen in that light. Our chief limitation is our size – we’re much smaller than people often think. I guess this means we ‘punch above our weight’.

Traditionally Greek professors and students have had a strong presence in UK universities. Moreover, in recent years Greece has experienced a “brain drain”, as many young professionals and academics have left Greece trying to build their lives abroad. How have Greek scholars contributed to the Hellenic Observatory and to research institutes in the UK? How could the experience of young Greek academics abroad be used for the benefit of Greece?

As a hub, the Observatory provides opportunities for scholars of Greece (young and old) to hold visiting positions with us and their input into our activities is invaluable. But, as they’re with us for fixed periods, they usually return to Greece or Cyprus. Hopefully, they return with a valuable experience from a university like the LSE, with its international reputation.

How far has the Hellenic Observatory influenced public debate about contemporary Greece and reached wider audiences beyond the academic community?

We’re not here to advance a particular view or frame; rather, our task is to enhance knowledge and understanding of different opinions and approaches. And we reach a much wider community – beyond the diasporas – to our events. We do this by drawing links between our ‘Greek’ topics and a wider international agenda. Even our events in Athens attract many non-Greeks.

Each year, we have over 26,000 visitors to our HO website (‘hits’). Our publications have been downloaded on 30,000 occasions. Every year, we attract over 2,500 guests to our public events.

What are the Hellenic Observatory’s plans for the future?

To expand the opportunities for collaborative projects between academics at the LSE and their peers in Greece and Cyprus, thereby making an even stronger contribution to policy debates that link us.

Greece is gradually recovering from an unprecedented year-long debt crisis, which has been the subject of numerous publications and debates and left deep marks in the country’s economy, society and political system. In your opinion, what are the most important aspects of this transformation?

The straitjacket set by the Memorandum conditions on Greece’s finances is not conducive to a stronger growth model. Surely, most would accept that proposition. Within these confines, Greece must build broad support at home for far-reaching structural reforms. The objectives are clear: more effective public institutions, stronger social support for those who need it most, and measures to make the economy more competitive. ‘Reform’ is a term often used across the spectrum, but beneath the talk there needs to be serious and consistent implementation. Education is a sector crying out for reform – it’s simply not serving the country’s future needs. But, too often, good plans are made and are then thwarted. The ‘Troika’ didn’t help to move the focus to long-term planning. However, I’m mildly optimistic: one of the positive legacies of the crisis is the increasing acceptance of a reform agenda, the content of which is shared by a fairly broad consensus.

In many respects, the Greek crisis has been part of a wider eurozone crisis. What lessons did the EU learn from the crisis? Do you think that the EU is turning away from the austerity as a dominant paradigm? Also, are recent reform proposals (i.e. by the French side) an indication that the eurozone is heading towards fiscal federalism?

The most important lessons from the crisis are for Greece and Germany. For Greece, the lesson is to have effective institutions – across sectors – and to focus the economy on the supply-side conditions for growth. For Germany, it’s that its own paradigm of ordo-liberalism doesn’t work so good for others. In a very diverse currency union, it makes little sense not to have fiscal federalism. Economies that fall into trouble need support – not the clumsy hammer of the bailouts, but effective long-term support for reform.

Many analysts seem optimistic about the European economy, but less confident about the future of European politics. The outcome of the recent Italian elections as well as the rise of the far-right German AfD have given fresh ground for concern. What do you think are the main challenges for European party politics?

Populism has been a response to the international economic crisis. It offers easy answers – often promising to reconcile irreconcilable objectives. In the midst of a crisis, it’s difficult to defeat populism. But Macron has shown a way. And with better economic times, the base for populism weakens.

That said, Europe needs to be brought closer to the needs of its citizens. ‘Europe’ must be made the solution to many of the problems people face – jobs; growth; security; climate change, etc. Opaque debates about narrow issues don’t meet the needs.

Apart from the debt crisis Greece as well as Europe have dealt and are still dealing with a refugee crisis, with major consequences for Europe’s politics and societies. How does the migration crisis affect European unity? Do you agree with analysts that speak of the resurgence of a West-East divide, which tends to replace the North-South divide, mostly created by the debt crisis? What can the EU do to face this new challenge?

The biggest current challenge is the lack of ‘burden-sharing’ between EU states and the limited ‘reach’ of EU governance at the domestic level. A ‘union’ needs burden-sharing across many fields, economics, migration, security, etc. A ‘union’ cannot be built on leaving another state to solve the problem. Europe is full of member states that feel virtuous in distinct areas: a strong economy, but not paying enough for common security or refusing mutual obligations in a fiscal union, for example. At present, Europe doesn’t have enough reach – whether its support for systems needing reform or where its societies are succumbing to populism and veering away from its core liberal values. Some of the illiberal developments in central Europe are terrifying. They are the cost of not having a full ‘union’, one that remains too superficial.

Living in the UK, one is “blessed” or “condemned” to live in interesting times, with Brexit on top of the agenda. What could be done to minimise the cost of Brexit both for the UK and the EU? How could Brexit affect the relationship between Greece and the UK? And finally, what kind of implications could Brexit have for the Hellenic Observatory and the LSE and for the cooperation between universities and research institutes in Europe?

The uncertainties of ‘BREXIT’ are very troubling. Few economists would predict economic gains for the UK – some would argue the possibility in the long-term. The economic hopes of the young are being sacrificed by the largely cultural fears of older voters. It’s important that the negotiations minimize the damage. But, the bilateral relations between the UK and Greece are built on strong foundations, across many fields. Flows of tourists and students won’t stop; London will still be a major centre for finance and shipping, etc. It’s that the likelihood is that in many areas, the UK will perform less well. Britain will continue to have leading brands – and, I’m confident, the LSE will continue to be one of the foremost. ‘BREXIT’ is very unlikely to limit the purpose, scope or activities of the Hellenic Observatory. Our mutual interest will continue – and my personal obsession with the Greek world will be undiminished.

*Interview by: Press Office of the Greek Embassy in the UK / Read the the Press Office’s monthly newsletter

I.L.

TAGS: INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS