The Hellenic Parliament Foundation organizes the exhibition “Feminism and Transition to Democracy (1974-1990): Ideas, collectives, claims”. Photographs, newspaper’s headlines, prints, manuscripts, posters and audiovisual documents, books and magazines present the ideas, the claims, the formation of dynamic collectives of an active feminist movement, which, in the 1970s and 1980s influenced Greek society, and brought to the fore of the struggle for women’s liberation. The exhibition runs from June 7 to December 17, 2017 at the Foundation’s exhibition center (Athens, Vass. Sofias 11)*.

“I’m not my father’s, I’m not my husband’s, I want to be myself,” “Woman without a man, fish without a bicycle,” “Women, turn you fear into rebellion,” “The personal is political.” These slogans summarize the emerging understanding of the social and political nature of relations between the two sexes in the context of the Metapolitefsi feminist movement.

After the collapse of the military junta in 1974 and during the period of transition to democracy (Metapolitefsi), new collective subjects emerge in the public sphere actively claiming their political visibility. Feminists of the time attempt to highlight the political character of gender hierarchies both in the private and public sphere by denouncing male dominance as an underlying condition of all social relationships. The slogan “The personal is political” summarizes in the best possible way the significance attached to uncovering the social and political aspect of gender relationships. Many women participate in movements that denounce discrimination against women, claim gender equality and seek to ensure women’s presence in politics.

In its unprecedented diversity and contradictions, the feminist movement of the Metapolitefsi lasted from 1974 until the end of the 1980s. During that time, the role of women, feminism and gender relationships emerge as urgent issues that both unite and divide.

Meanwhile, the State starts to acknowledge feminists issues by establishing institutions responsible for gender equality and attempts to reduce institutional discrimination against women. The Constitution of 1975 establishes full gender equality for the first time. This constitutional recognition of equality brought about later changes to family law, labour law and laws on education, social security, maternity, health, and criminality.

From women’s organizations to autonomous women’s groups

Following the restoration of democracy, the structure of the female movement became quite diverse. Women’s organizations, whose operation was interrupted due to the military junta, were reestablished. The Greek League for Women’s Rights (Syndesmos gia ta Dikaiomata ton Gynaikon/SDG) is an illustrative example. The SDG was founded in 1974 and participated actively in women’s activism during the period 1974-1990. It also played a crucial role in establishing the new institutional framework on gender equality.

At the same time, nation-wide women’s organizations were established in connection to, or as part of, political parties. This category includes three large-scale nation-wide women’s organizations: The Democratic Women’s Movement (Kinisi Dimokratikon Gynaikon/KDG) politically linked to the Euro-communist party (KKE Interior), the Federation of Greek Women (Omospondia Gynaikon Ellados/ OGE) linked to the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and the Union of Greek Women (Enosi Gynaikon Elladas/EGE) politically linked to PASOK. During the same period, political parties, youth wings and trade unions gradually establish women’s sections, or committees with a focus on working women’s issues.

Independent women´s organizations and groups also emerge as an alternative to the prevailing political landscape where political parties employ, educate and guide women through their organizations or party mechanisms. Independent initiatives by women attempt to think and act beyond parties and male influences, arguing that this way of operation is a precondition for feminist policies. The first independent feminist organization is founded in Athens in 1975 under the characteristic name “Movement for the Liberation of Women” (Kinisi gia tin Apeleftherosi ton Gynaikon/KAG), an initiative of left-wing women. In 1978, the KAG starts publishing the newspaper For the Liberation of Women (Gia tin Apeleftherosi ton Gynaikon). The following year, women’s groups are established in the Law School, the Faculty of Philosophy, the Medical School, the Faculty of Biology, the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, higher technical schools etc. During the 1980s, there is a proliferation of independent women’s groups in districts of Athens or in major provincial cities that will create the diverse and dynamic feminist movement of the period of Metapolitefsi.

Women’s Claims

The demands of women during the period of Metapolitefsi were largely structured around three important subjects: family, women´s right to control their bodies and participation in political life.

As far as was family and family law were concerned, the period was quite favorable, given that the State was also seeking to adapt family to the new constitution of 1975 as well as to harmonize Greek institutions with the rest of the EU. Most of all, this was an issue of concern for all women from different backgrounds and emerged as a crucial demand of women’s organizations. At the same time, the issue of family was at the core of second-wave feminist discourse, given that this is an area where power relationships between genders are primarily displayed.

Law 1329/83 modernized family law and adapted it to the constitutional principle of gender equality. The law, which brought about significant changes in several institutions, abolished the concept of the patriarchal family -in which the man was the head and the leader of the family; the institution of dowry; the obligation of women and children to take the father´s last name, while instituting that both spouses are compelled, depending on their strength, to contribute to the family needs; that children’s upbringing and education should be done “without discrimination of sex”; the possibility of spouses to claim participation “in the property acquired during marriage”; consensual divore; equal rights of children born in and out of wedlock and special provisions for single mothers.

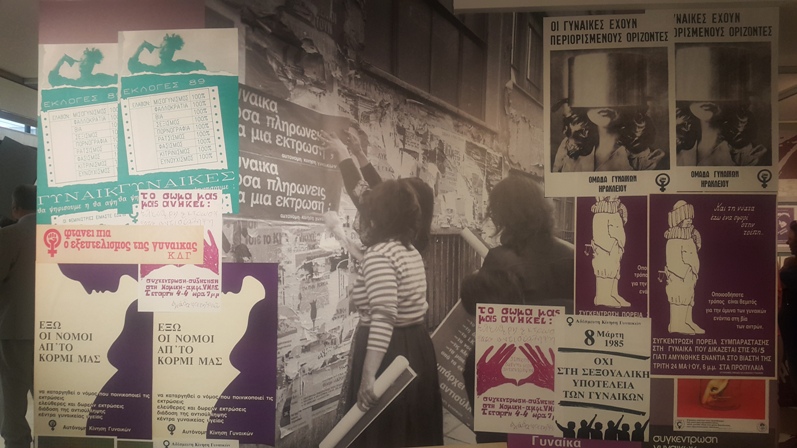

In the matter of the self-determination of women, feminist groups argued that male control over the female body is a key factor in perpetuating male dominance. The right of women to have control over their bodies, their ability to decide whether and when to have children, the freedom of sexual orientation, and the defense of the female body against all efforts to violate its freedom emerge as central demands in the context of radical feminist theory. The heart of the matter is women’s unimpeded right to contraception and abortion.

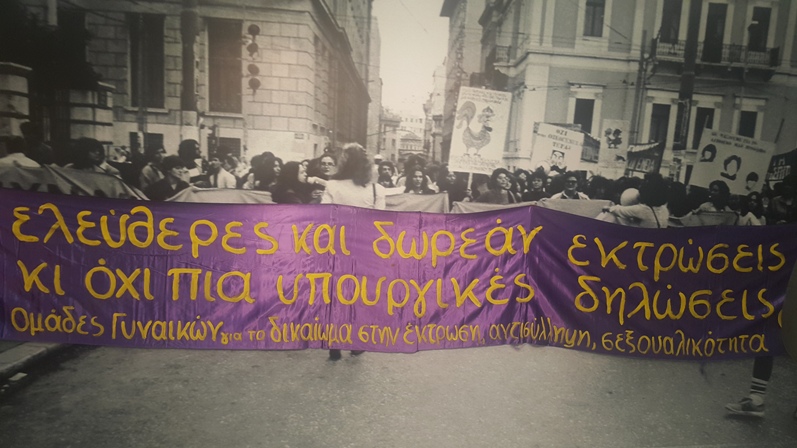

During the Metapolitefsi women were, to a large extent, unaware of contraception methods and tended to resort massively to illegal abortions. Feminists, including the Movement for the Liberation of Women (Kinisi gia tin Apeleftherosi ton Ginaikon) and the Movement of Democratic Women (Kinisi Dimokratikon Ginaikon) argue that contraception is a precondition in order for women to have control over their body and, through a campaign initiated by the Autonomous Women’s Movement (Aftonomi Kinisi Ginaikon), they demand the unimpeded right to free-of-charge abortions — this demand was also expressed by the Women’s Union of Greece (EGE) and many women’s groups, albeit with some differences. In the same context, the Women’s House (Spiti ton Ginaikon) took the lead on protests regarding the condemnation of rape, sexual harassment and all forms of gender-based violence both inside and outside of the family. Abortion was finally legalized in 1986.

In the matter of participation in politics, towards the end of this period, the consistent and extreme lack of representation of women in decision-making centres, and especially in the Parliament, is regarded as a significant democratic deficit by the feminists. Therefore, as is the case elsewhere in the Western world, arguments regarding the participation of women in political life through quotas become more and more relevant. The League for Woman’s Rights (Syndesmos gia ta Dikaiomata tis Gynaikas) and large-scale women’s organizations, as well as party sections, demand the adoption of legislative measures that will oblige political parties to stop ignoring women when drawing up their candidate lists. This situation causes various and diverse reactions: men politicians react as this would limit the number of male candidates and some women politicians disagree arguing that their careers should not be based on positive discrimination. In addition, not all feminists agree on this claim they believe that the elimination of gender-based discrimination is not necessarily related to the physical presence of women in politics. The demand fails to be addressed in the 1980s and is only settled in the early 21st century.

Activism

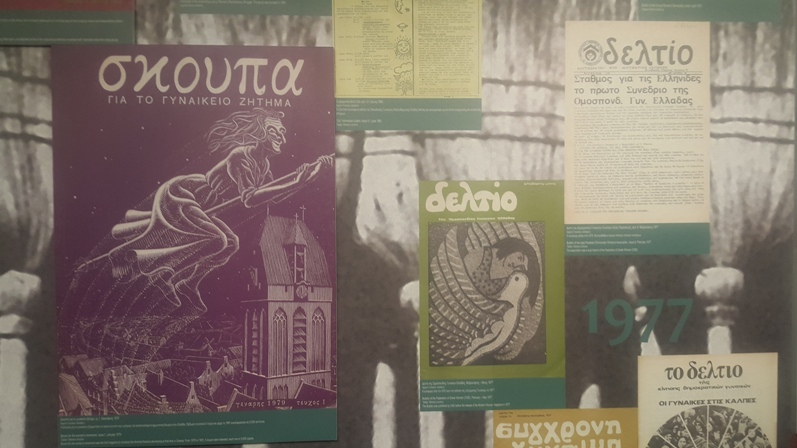

Feminist activism of the time comprise a wide range of publications and demonstrations, public gatherings, exhibitions, debates, meetings to coordinate feminist action, film sessions, music events, excursions. Through these activities, the feminists are attempting -and will manage- to acquire a distinct political presence. By publishing theoretical texts or manifestos on feminist politics, the women’s movements express their desire to establish themselves as collectives, to disseminate their concerns and to contribute to the creation of a public space for the exchange of views and ideas.

At the same time, these publications attempt to link the women’s movement with theoretical discourses and international trends and to present the movement’s history. Skoupa (Broom) (1979-1981), is probably the most important feminist journal of the first feminist period: Its articles informed readers on the history of women’s demands in Greece, the processes taking place within the feminist movement and the relevant concerns voiced by women in other countries.

The Editorial Team of Women (Ekdotiki Omada Ginekon) also founded in 1979, published five books which, along with the books translated and published during the same period by other Greek publishing houses, form a relatively rich corpus of theoretical and political feminist texts. Its pages reflect the feminist movements of the time: socialist feminism, radical feminism, equality and difference feminism.

Books and brochures were used to shape and propagate the ideas of feminism during Metapolitefsi, denouncing sexism and male dominance, misogyny in the media, the importance of the struggle to change the female consciousness and the fact that the movement concerns all social classes.

Ideas are also cultivated and disseminated in spaces that women create in order to meet, discuss and have fun. Women’s houses, bookstores, cafes and hangouts host feminist activities and become reference points for post-transition feminism.

Women also propagate their ideas on the streets. They use posters, pamphlets or the collection of signatures. The feminists hold demonstrations to struggle against all issues in their agenda: beauty pageants, family law, abortion, violence and rape, the right of women to circulate freely etc. These demonstrations will go down in history for their colourfulness, their fanciful slogans and their dynamic nature.

Towards the end of this period, feminists are clearly focused on feminist studies. The focus on women’s or feminist studies -regardless of their name- demonstrates the tendency of the feminism of the Metapolitefsi -and second-wave feminism in general- to turn to science in order to identify and denounce its profoundly gendered character and its role in perpetuating power relationships between genders.

After the 1980s

Towards the end of the 1980s, feminist demands had achieved considerable success. At the institutional level, the laws on equality had steeped into the legal culture of Greece, despite some remaining inequalities. The feminism of Metapolitefsi managed to identify discriminatory behaviors and to link them with the power relationships between men and women and influenced some sexist perceptions and practices… However, for large part of the population, discrimination against women remained in place as the ideological and social rule. As regards social practices, tendencies to perpetuate gender hierarchies co-existed with attempts to change or overturn them.

By the 1990s most feminist voices of the Metapolitefsi had gone silent. Many autonomous groups had dissolved, feminist journals stopped being published and the presence of women’s demonstrations in the streets of Athens and other major cities became increasingly scarce. Feminists started to refer to a “crisis” of the feminist movement. Women’s organizations continued to operate, influenced to a greater or lesser extent by feminist discourse and practices. In that period, actions to address women’s issues were taken under the initiative of the European Union (EU) and international organizations. A series of directives on equal opportunities between men and women were adopted by the EU and programmes for raising awareness, preventing and combating violence against women and promoting equality policies were put in place. In this context, it is worth noting that women’s networks were created at the EU level and that support was granted to studies on gender and equality in Greek Universities.

*Source Material: Texts by Maria Repoussi and Angelika Psarra, members of the Expositions’s Scientific Committee, translated by Marilleia Tilly

I.L.