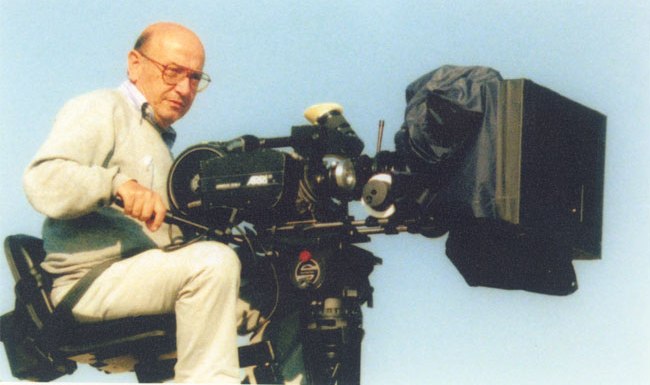

It has been fifty years since the emblematic in Greek cinema history film “Reconstruction”/ (Anaparastasi) (1970) by Theodoros Angelopoulos was released, described at the time by film critic Vassilis Rafailidis as the first “grown-up” film of Greek cinema. The ‘last Modernist’, internationally acclaimed filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos was born in Athens in 1935. Following film studies at the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC) in Paris, he worked as a journalist and film critic for the Athens newspaper “Dimokratiki Allaghi” from 1964-1967 and for the “Modern Cinema” magazine. He made his first short film “The Broadcast” in 1968. From the 1970s onwards, he ranked amongst the most important European auteurs. His films dealt with historical and existential themes and ancient Greek myths in modern Greece. Angelopoulos died in 2012.

His impressive filmography of multi awarded films consists of Forminx Story (1965), The Broadcast (Ekpompi) (1968, 22’), Reconstruction (Anaparastassi) (1970, 98’), Days of ’36 (Meres tou 36) (1972, 105 min.), The Travelling Players (O Thiassos) (1974-’75, 230’), The Hunters (I Kynighi) (1977, 168’), Alexander the Great (O Megalexandros) (1980, 210’), Athens, Return to the Acropolis (Athina, epistrofi stin Akropoli) (1983, 43’), Voyage a Cythera (Taxidi sta Kithhira) (1984, 120’), The Beekeeper (O Melissokomos) (1986, 122’), Landscape in the Mist (Topio stin Omichi) (1988, 127’). The Suspended Step of the Stork (To Meteoro Vima tou Pelargou) (1991, 143’). Ulysses’ Gaze (To Vlemma tou Odissea) (1995, 176’), Eternity and a day (Mia Aioniotita kai mia Mera) (1998, 137’), Trilogy I: The Weeping Meadow (Trilogia I: To Livadi pou Dakryzei) (2004, 170’), Trilogy II: The Dust of Time (2008, 125’).

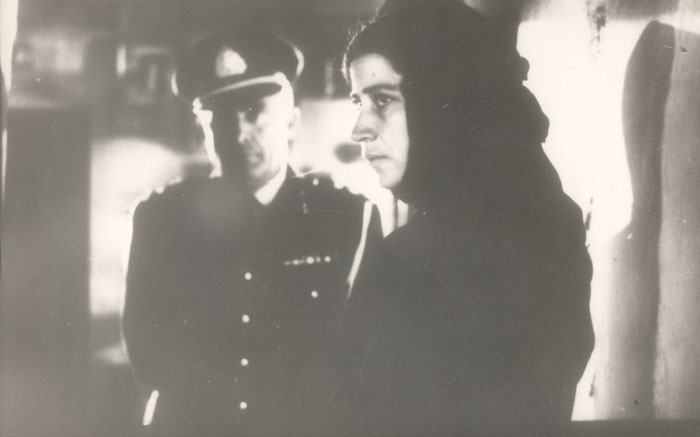

Yannis Balaskas, Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

Yannis Balaskas, Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

“Reconstruction” won Best Director, Cinematography and Actress awards as well as the Critics Prize at Thessaloniki Film Festival (1971), Best Foreign Film award at Hyeres Film Festival (1971), Georges Sadoul Award (1971) and Special Mention, FIPRESCI (Federation Internationale de la Presse Cinematographique) at Berlin International FF (1971), and it was screened February 2020 in the framework of the Berlinale Forum 50 years celebration programme. It has been voted (in 1986 and 2006) by the Panhellenic Union of Film Critics (PEKK) as one of the best Greek films.

The film is based on an actual event, the murder in a remote village of Epirus, in Northwestern Greece, of a migrant Greek worker on his return from Germany by his wife Eleni and her lover Christos, who upon examination by the police eventually accuse each other of the crime. The reconstruction of the events is led by a magistrate, although the actual crime is never depicted on screen. Meanwhile, a TV crew (including the director himself) conducts its own investigation, documenting circumstances of the crime and local societal values. From the very first sequence, the audience knows who was killed, how and who did it. The film closes as it began, cutting back to the husband’s return to indicate an order which has been ruptured.

Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

Tymphaia is a village on the foothills of the Pindus mountain range in Greece, and people have lived heresince classical times. The population was about 1250 people in 1939, but by 1965, only 85 remained. The film begins with a sober voice-over description of the setting, whilst Theo Angelopoulos presents a sober reconstruction of a crime committed here, seemingly a crime of passion. Is this a retelling of the timeless story of Clytemnestra murdering her husband, or is this act of violence connected to the socioeconomic conditions in the barren mountain village described in the film’s beginning? Jumping between past and present, Angelopoulos’s virtuoso feature debut explicitly avoids answering this question, allowing it to hang in the air instead by juxtaposing the crime with documentary-like impressions of living conditions in the village. Giorgos Arvanitis’s black-and-white images lend additional austerity and bleakness to the wintery impression of a dying community.

Toula Stathopoulou (centre), “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

Toula Stathopoulou (centre), “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

As Angelopoulos mentioned in an interview, he was not interested in the real story per se, it was not the first time he read in the newspaper that a Greek woman had killed her husband. In the Epirus region, the most underdeveloped in Greece, it was fairly common. He wrote the script, after conducting on the spot journalistic research, talking with the villagers and relatives of the murderess. The murder serves Angelopoulos solely as the inciting incident for a report on a Greek village in this region. He wanted to attempt a double reconstruction, i.e. a reconstruction of the facts that he was either told or as informed through court documents, as well as a reconstruction of the events conducted by the police with the guilty parties. “The film functions on these two levels: on the level of the police’s reconstruction of the events, and of my reconstruction in the form of interrogations. The film shifts back and forth between these two levels, without giving rise to a logical continuity. The film thus ends, for instance, with a scene that should have been at the beginning: the murder. But it’s the murder as it appears from the outside”. Angelopoulos was interested in the gradual death of a region, a process that can be extended to the whole of Greece, not in the story as a criminal case.

Visually the film is in stark contrast to the illusionistic approach of cinema. The muddy roads of an Epirus village constitute a metonymy of the harsh realities of life in post war Greece. The film offers a different portrayal of Greece, which was usually depicted as an idyllic tourist attraction. The long takes which have their own rhythm, minimal editing and the absence of close ups were a trade mark of Angelopoulos distinct film style. “Recontruction” was the first film in the New Greek Cinema Movement.

Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

Toula Stathopoulou, “Reconstruction” (1970) – source: Theo Angelopoulos official site

As Vrassidas Karalis (“A History of Greek Cinema”, 2013, p.154) noted: “By representing the structures of power that permeated the consciousness and the unconscious of their characters, the new directors wanted to raise awareness of and even to denounce established “truths” and to incite action. By doing so, they avoided all forms of psychologization, melodrama, or emotional plethorism. The conflict between a human being and its social environment was depicted in its ordinary manifestations: as an inability to find personal fulfillment, emotional reciprocation, or interpersonal understanding rather than as grand moral dilemmas, heroic acts or superhuman virtues. The anti-Hollywood aesthetic of the movement would be its dominant parameter until its demise”.

The female protagonist is an example of the antihero formed by New Greek Cinema: “not the common man or the sympathetic rascal, but the unintentional criminal, the confused bystander who rejected the positive values of society and felt existential dysphoria within the negative values of his subconscious. From Angelopoulos’ assassins to Ferris’ transcendental murderess, it was the conditions around criminal behavior that interested the new directors. It was not the criminal as a human being, but the crime as the end result of many imponderable factors beyond the understanding or control of the specific character that the directors wanted to represent” (ibid). New Greek Cinema changed Greek film thematology and narrative codes and became dominant in Greece for the next 15 years.

Special thanks to Foivi Oikonomopoulos for pemitting the use of photos from Theo Angelopoulos official site.

F.K.