Where is the limit between fiction and reality in a documentary? How does one compose the portrait of a dear friend when he has stepped into the hereafter? In her recent documentary “Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope“, director Eleni Alexandrakis portrays Kostis Papagiorgis, an important essayist and translator. Avoiding sentimentality, her film is a refreshing exercise of intertextuality, in which excerpts of his texts along with testimonies coming from important representatives of the Greek intellectual scene compose an image of the late essayist.

Eleni Alexandrakis was born in Athens in 1957. She studied film at the Sorbonne University, Paris I and at the National Film and TV School of England. She has written, directed and produced several fiction films and documentaries, among which: “A Drop in the Ocean” (fiction, 1995), “Easter is in the air” (documentary, 1999) “The Woman who longed for Home” (fiction, 2004) “Angel and the Weightlifter” (fiction, 2008). She has received several prizes in Greece and abroad.

Alexandrakis talked to Greek News Agenda* about her latest documentary “Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018) that won the Greek Association of Critics Award at the 20th Thessaloniki Documentary Festival. As there was scarce visual material of Papagiorgis, Alexandrakis stresses the difficulty of composing his image from scratch based on the testimonies of the intellectuals, artists and people close to him. A dear friend of his and his wife, Alexandrakis says she was compelled to reread his books after his death, which was the inspiration for the film. Alexandrakis also talks about the inextricable link between his course of life and spiritual evolution which is reflected in his works.

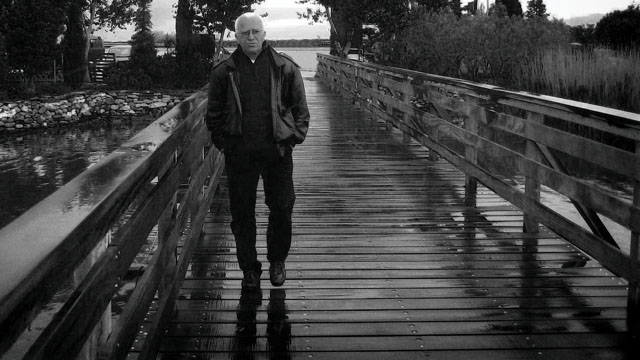

Photo of Kostis Papagiorgis in “Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018)

Your documentary undertakes the difficult task of visualizing the absence of an important intellectual like Kostis Papagiorgis. Papagiorgis avoided appearing in the media. How did you deal with the absence of visual material depicting him?

Kostis Papagiorgis avoided self-exhibition like the plague, so one can’t find any live pictures of him anywhere. The only live images that exist and that I used in my documentary are various home movies, and some silent shots of him that Nikos Perrakis had filmed in 1994 for his documentary “Polis” (shots that he ultimately never included in the his film). So I had to compose a jigsaw puzzle of Kostis’ personality through the images that his texts inspired in me, combined with the words of the people who knew him. That was extremely challenging for me as I felt that I was rebuilding his image from scratch and that I was creating a ‘musical score’ of the ‘notes’ that compose his life. Intellectuals, artists, relatives or ordinary working people added their own touches to the portrait.

What prompted you to do this film and what was the influence of your friendship with him on the final product?

I was friends for 20 years with Kostis Papagiorgis and his wife Rania. Missing him after his death plunged me into rereading his books so as to “bring him back” or, at least, to shorten the distance between us and the “beyond”. Very soon, without realizing it, I started imagining a film, which was inspired by his words. I was also impressed to discover, in a different way now, how similar his life was to his writings. Without being autobiographical he writes about life and the “human condition” through his own experience with an incredibly clear insight. His texts are very personal, he has a very particular use of language and his approach to passion and philosophy is totally unconventional. The fact that I was seeing his features so clearly in his books gave me the urge to narrate in a film the story of his life through his thinking.

“Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018)

Although Papagiorgis did not pursue an academic education, he attended philosophy courses freely during his stay in France. To what extent do you feel that this “French period” influenced him?

Papagiorgis was self-taught as he always despised academic education and positions. He was too much of a rebel to be a classic student. He had such self-discipline and a brilliant mind that he managed to learn French entirely on his own and to study philosophy by himself. While Kostis lived in Paris, locked up for days and nights in his little “chambre de bonne” he read Heidegger’s “Being and Time” forty times, among the many other books that he also studied. Papagiorgis admired western civilization, and as he used to say, he really started to understand Plato through reading Heiddeger. This of course influenced and inspired his thinking, as well as the 19th century novel, which he adored. But all this served mostly to make him look inside his heart and soul and through this inner gaze to look clearly at the particularities of his own personality and country. After returning to Greece he felt he should stop writing “with his hand on the library” but he should be writing “with his hand on his heart” which led him to write experientially on passion, drunkenness, jealousy, misanthropy, death, sympathy, Greek history, Papadiamantis Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche and a multitude of other subjects. Writing through his own experience he expresses himself on the universal problems of humanity and mankind. After living for eight years in Paris, he translated 54 books from French of the biggest thinkers of western civilization.

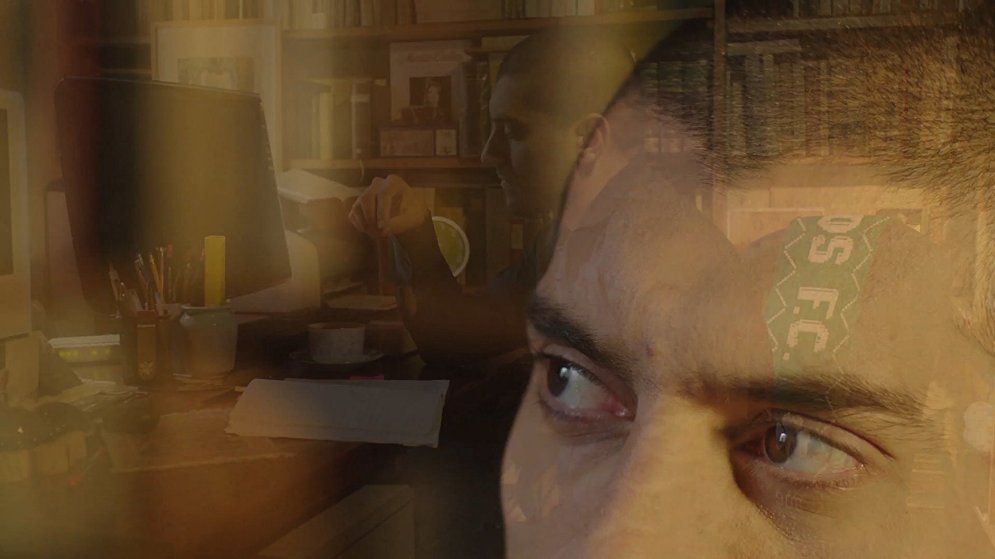

Agyris Pantazaras in “Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018)

Papagiorgis’ rich oeuvre of translation includes works by Βalzac, Foucault, Cioran, Lyotard, Pascal, Sartre, Bergson, Derrida etc. Who were his favorite thinkers?

I believe Balzac, Cioran, and Pascal are probably among his favorites. To show his love of Balzac I give you below a small extract of Papagiorgis’ introduction to his Balzac Anthology of “The Human Comedy”:

“Including in his capacity as a novelist the historian, the physiologist, the alchemist, the psychologist and the sociologist, Balzac achieved the impossible for today’s circumstances: he became the mirror of a society that had been struck from the effects of French Revolution, the Napoleonic wars and the Restoration.[…] It would not be inappropriate to think that this hypothetical interview* with Honoré de Balzac allows us to sketch the features of the 19th century itself.”

*Kostis means here that the anthology that he has made of Balzac’s phrases is like a hypothetical interview

Akilas Karazissis, Agyris Pantazaras in “Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018)

Which aspects of his personality did you focus on?

Kostis always said that to write a book he needed to have experienced a stirring fact or event. He needed something that would create a shaking turmoil in his heart. While preparing the script and during the shooting of my documentary, I was permanently looking through his writings to discover those stirring moments and details of his life that made him write each one of his books and the crucial points that made him go so deep in the research of his subjects. I kept trying to understand what was his relation to misanthropy and to negativity, as he proves to be especially accurate in describing those concepts. I tried to find in every book of his the extract that I thought reflected his character in the best way. I also wanted to show that, regardless of the fact that he wrote so often about the dark side of things, he was a very sweet man who never thought highly of himself. In fact, Papagiorgis is characterized by a duality. That is the reason why in this documentary / portrait of his, I chose to have two different actors reading his texts. Argyris Panzaras reads extracts from Kostis’ notebooks and rare interviews in the press, and Akilas Krazissis reads extracts from his books.

“Kostis Papagiorgis: The Sweetest Misanthrope” (2018)

Poetry is often mentioned in your documentary. What was Papagiorgis’ relationship with poetry and how did you balance between poetic vision and realistic depiction, fiction and reality in your film?

The poet Michalis Ganas says in the film that although Kostis pretended not to like poetry, in fact he understood and loved poetry very deeply and selectively and actually Papagiorgis’ writings are so poetic that any poet would envy them. In my documentary / portrait of Kostis Papagiorgis, who is one of the most important essayists of contemporary Greece, I spontaneously followed the inspiration that my late friend and his writings gave me. This ended up necessarily as a poetic approach: I set up images that I mixed with the people who speak about the essayist, respecting a rhythm and a melody that, I believe, makes this film true and non-academic, and possible to follow even for those who are not familiar with Kostis’ books – and, I hope, enjoyable.

* Interview by Florentia Kiortsi with the contribution of Magdalini Varoucha.

Κostis Papagiorgis, the sweetest misanthrope | Trailer