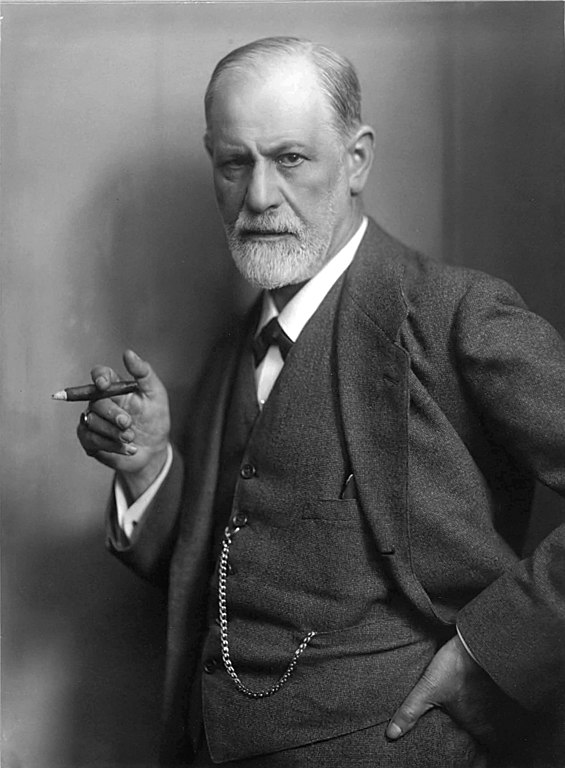

Sigmund Freud was already “a man of mature years” when he travelled to Athens for the first and last time in 1904, accompanied by his younger brother, Alexander. Greek history and mythology deeply inspired him since childhood, but the trip was the result of unexpected changes to his travel plans that year.

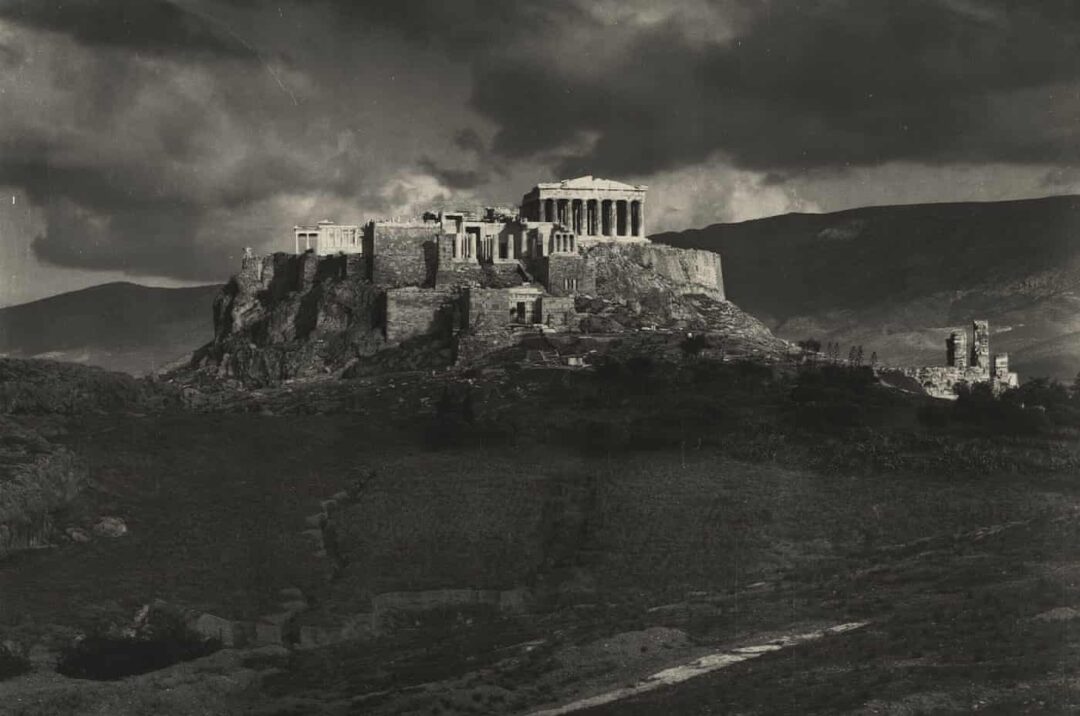

Located on a limestone hill high above the city, the Acropolis of Athens in Greece is one of the most important archaeological sites in the world. Over time, the site has been a fortress, a religious centre and a major cultural monument strongly associated with ideas of beauty and eternity.

When Freud reached the top of the Acropolis hill, gazing toward the sea, he experienced a feeling of astonishment and disbelief that puzzled him for decades. In 1936, he wrote about his experience in an open letter to French author Romain Rolland – the text, titled ‘A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis’ is now considered a key point of reference.

The exhibition Tracing Freud on the Acropolis opened on July 26, 2023 and will run until 7 January 2024 at Freud Museum London bringing together archives, images and objects exploring Freud’s journey to Greece, and his encounter with the Acropolis. This exhibition is organized with the kind support of the Acropolis Museum, the Hellenic Society for Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Group Psychotherapy and the Institute for Digital Archaeology.

The exhibition’s curator, Marina Maniadaki, writes for the Athens News Agency, exploring the father of psychoanalysis’ relation to the Acropolis and to ancient Greek thought*:

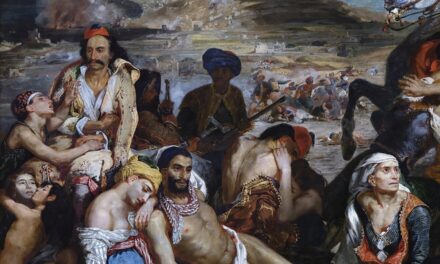

Autumn of 1904: In Athens, September has arrived warm and civil engineer Nikolaos Balanos is carrying out extensive restoration work on the Acropolis; recently a systematic excavation revealed the sacred rock’s stunning antiquities. Scores of famous people from the all over the world flock to Greece to admire its monuments.

In the morning of September 4, a middle-aged man climbs the rock slowly, almost piously. Despite the posture of his body, which shows impatience to reach the top, his steps are steady and every now and then he raises his head to see what is being revealed to him. Another man, obviously younger, is walking with him. It is his brother, Alexander, ten years younger than him. “For this visit to the sacred rock I wore my good shirt” the Austrian neurologist-psychiatrist Sigmund Freud will later confess to his wife, talking about fulfilling of one of his life’s dreams. He visits the brilliant exemplar of ancient Greece, from which he borrowed the core of his scientific theory. The methodology of psychoanalysis like that of archaeology, you dig into the past to interpret the future, according to Freud’s definition of the technique, which he himself has invented. In fact, in his work “The Etiology of Hysteria”, he will articulate that “just as archaeologists discover hidden ruins, so the psychoanalyst can excavate a person’s past, conducting an archaeological investigation of the mind”.

History will show that Freud’s relationship with Greece and Greek thought is deep and multidimensional. He himself knows about ancient Greece from the texts of ancient Greek literature and through his contact with the cultural currents of the West. His psychoanalytic theory stems from this relationship.

As a Jew, he is proud of his Judaism because he belongs to the people who gave the Bible to the world, but he renounces dogma and religion, which allows him be open to different cultures and theories. He passionately searches for and studies the sources that reveal the roots of ancient civilizations. His office in Vienna is full of finds, mainly from excavations in Egypt and Greece. His collection includes about 2,500 thousand pieces, among which several phallic symbols from Pompeii. His inspiration, however, as he says in his circle, is a bust of the tragic Sophocles, the “father” of the legendary Oedipus.

Freud, looking for answers on human sexuality, believes that it can be better understood through myths, because they are closer to the unconscious. Myths, he says, can describe things unknown to the person about themselves. Every myth is a focal point around which many of our fantasies and desires are woven; what is more, a myth acts as a carrier of elements of collective memory. But every myth also has a dark side, which can be explored by the psychoanalytic process. This process does not just investigate the obvious elements of the myth, but also delves into in the latent and its relationship with the obvious. For Freud, who persistently and devotedly studies ancient Greek literature, the ideal reservoir from which to draw myths is that of ancient Greek tradition.

According to the interpretation of the late doctor of Philosophy, fellow at the International Council of Psychologists and founder of the Hellenic Center for Mental Hygiene and Research, Anna Potamianou: “Freud, by selecting the ancient Greek myths of Narcissus and Oedipus, in fact suggests to us some forms, which organize our mental life. With […] the help of Narcissus, who let himself die admiring his image, he presents us with two courses that we could follow in life. One is to move slowly through ourselves into relationships of recognition with the other, of the different, and to finally arrive at the recognition of our own diversity, our sexuality, etc. The other course is to burn the bridges with the outside world and concern ourselves only with ourselves, denying and distancing ourselves from external reality, thus falling pray to this internal self-destructive drive, that Freud calls the ‘death drive’”.

A far as the myth of Oedipus is concerned, Freud chooses it as a form through which to demonstrate that ultimately, the human psyche needs certain fundamental representations that provide the concept of the difference between generations, the sexes, and how the law works – or does not work – in relation to hubris.

Of course, the scientist’s relationship with the ancient Greek imprint is not limited to the two emblematic figures of Greek mythology (Narcissus and Oedipus), which he borrows to establish his theory. He has long been studying the basic question of the ancient Ionian philosophers: how the world arose from the universe, that is, how we came from chaos to a world organized with law and order. On this same question he will base his scientific conception of the birth of beings: how a child starts from the point, when it does not distinguish between the “I” (that is, what we call our consciousness of ourselves) and the “non-I” (i.e. the rest of the world), to differentiate between the twο, having in the meantime internalized certain values from its identification with parents and other persons in its environment.

“By the evidence of my senses I am now standing on the Acropolis, but I cannot believe it”

Sigmund Freud, 1936

His awe for the thought of the ancient Greeks and his admiration for their achievements keep him constantly connected to the place, which he has not yet been able to visit. Until the fall of 1904, that is, when he has lived 48 years of his life. This September, finally, here on the Acropolis, he will live an experience, which he will “dare” to describe only 32 years later in a text entitled “‘A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis“. The text will be addressed to the French essayist and art historian Romain Rolland and will be included in an honor volume for his 70th birthday. As Freud himself tries to explain to his French friend, that visit to the Acropolis made him experience a passing hallucination or perhaps a dream, a “strange and as of yet inexplicable split personality.” At the beginning he will monologue “so, all this does exist, just as we learned in school!” and later he won’t believe his senses… “by the evidence of my senses I am now standing on the Acropolis, but I cannot believe it” . In the end he exclaims “no, what I see here is not real!”

“Attributing decisive importance to the event of 1904, which haunted him for years, Freud in 1936, perceives it mainly as a conflict between presence and absence” is the interpretation of Ilias Papagiannopoulos, adjunct professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Piraeus and writer of the book “Froyd the the Acropolis. An a-topography” (2019, in Greek).

*translated and abbreviated from original text in Greek

I.L.

TAGS: ACROPOLIS | ANCIENT GREECE | PHILOSOPHY | TRAVEL