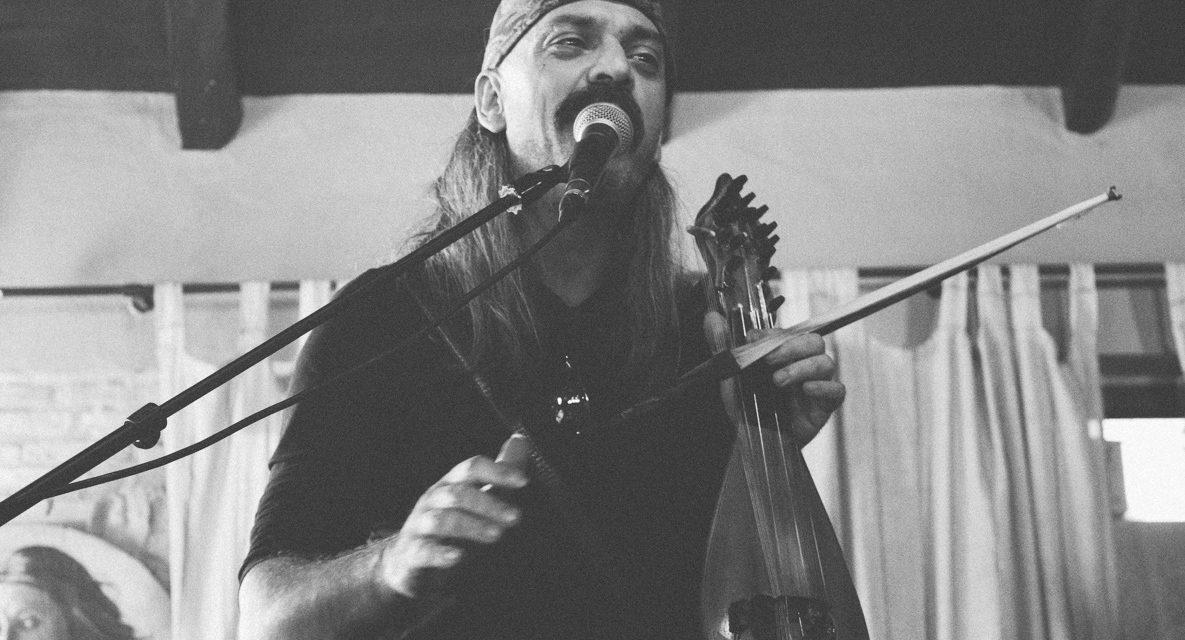

Lyra player, singer, songwriter and theoretical physicist “Chainis” Dimitris Apostolakis is a founding member of Chainides, a Cretan music group formed in 1990 by a group of friends, most of them students then at the University of Crete. The group’s name comes from the world ‘chainis’ meaning the fugitive rebel in Cretan dialect. The group are inspired by the vast legacy of traditional Cretan music and their lyrics are in the Cretan Greek dialect. Their discographical debut, titled “Chainides” released in 1991 was warmly received by the public.

Over the years, Chainides have collaborated with several well-known musicians and singers, performed extensively in Greece around the world and recorded 11 studio albums. In their live performances, Chainides blend their own compositions and songs with new arrangements of themes and songs from traditions such as those of Turkey, Afghanistan, Bulgaria and the wider eastern Mediderrenean region.

Chainides’ latest album “Pera apo ta synora” (Beyond Borders), was released in 2014 with the participation of legendary lyra player Psarantonis and traditional music group Mode Plagal, based on the lyrics of Lorca, Borges, Sultan Abdal, Rilke and Pushkin and blending Cretan music patterns with motifs from flamenco to rock and jazz.

Chainis D. Apostolakis, along with Psarantonis, Chainides and modern dance troupe “And yet it moves”, re-interpreted the 17th century Cretan poem Erotokritos as a mixed spectacle with music, acrobats and references to medieval folk festivals. The performance was first presented in 2014 as part of the Athens and Epidaurus Festival and has been re-run every summer since. His most recent endeavour is the publication of a collection of short stories called “Ftou xeleutheria gia olous!” (Everyone get free!, 2015).

Chainis talked to Greek News Agenda* about how Cretan music has evolved through the years, the anthropological and geographical uniqueness of Crete, the tradition of Anogia, the forgotten role of the lyra player as a master of ceremonies and how Erotokritos was the last European epic saga to be sung by the people.

One of Chainides’ biggest hits is ‘O Akrovatis’:“The Acrobat” (1994), Lyrics & Music: Dimitris Apostolakis: “Everybody, take a look at how the acrobat tries to balance Everybody, take a look at how the stranger doesn’t get dizzy. Take a look at the acrobat; even if he falls he laughs and never cries. Take a look at the bird of the desert that has a bleeding wing. It’s still flying against time, even if it’s going to suffer the shot of death. When time is against you, the price you pay in order to fly is to be left alone. Everybody, take a look at me, I’m asking for nothing else. (look at me) that I have broken wings on my back and I am trying to keep the balance like an acrobat. The day has passed and you still are not there, don’t cry my beloved one.”

Why do you think Cretan traditional music has remained alive for so long and is still evolving?

I consider labels like “traditional” to be tricky. Let´s start from the beginning. In the old days, people played instruments and sung without knowing that what they were playing was Cretan music. In each village there were musicians and enthusiasts that sung and danced all kinds of music: rizitika from the Lefka Ori mountains of western Crete, syrta from Chania, kontylies from eastern Crete, rembetokritika or tampachaniotika -as they are called- from the urban north coast of Crete, songs from Kalamata and Smyrna and religious psalms, without knowing what kind of music it was. They just knew them as tunes.

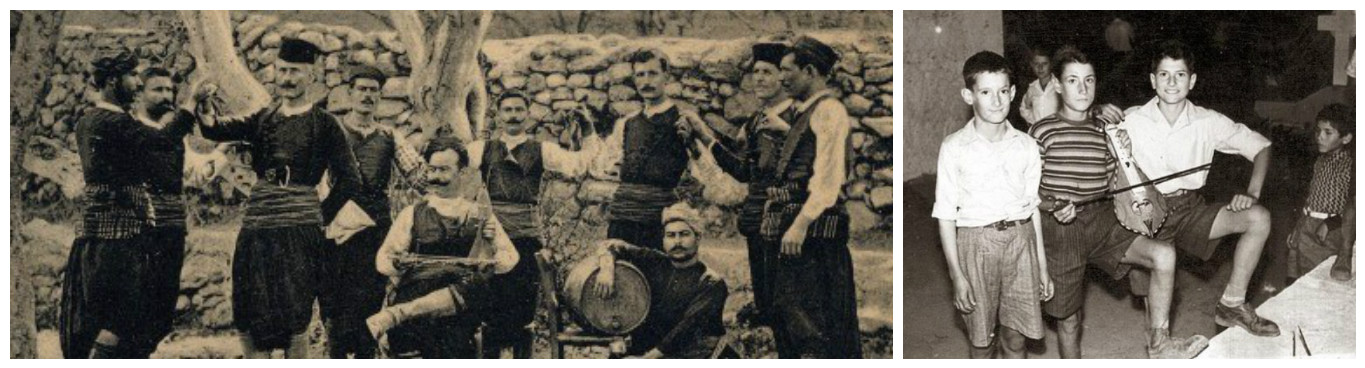

Furthermore, because of the rugged terrain of Crete, each small region had its own instruments. For example, in the times before and after WWII in eastern Crete, you could find groups (zygiés) who used a violin and a guitar, or a lyra played with a bow with bells and a daouli drum. In western Crete you had the lute and violin, played differently from the eastern parts of the island. In the north coast cities you could see boulgariá, an instrument like tabmouras or saz. In central Crete you had lyras escorted by mandola or mandolin. The mandolin was a fundamental instrument, played along with askomandoura, a type of bagpipe and a daouli drum. That is to say, people played whatever was available.

After the 70s and 80s you have a stylization of Cretan music. If you play pre-war recordings to young people involved with music now, they will not recognize it as Cretan music. When I met the first woman who sang Cretan songs, Lavrentia Bernidaki, sister of the great lute player Giannis Bernidakis or Baxevanis, she told me that in their group, Andreas Rodinos played viololyra (an instrument that’s a cross between the violin and the lyra), her brother Giannis played the lute, and they also had an accordionist and a clarinet player. This combination of instruments would be considered unthinkable in today’s Cretan music.

In the last couple of decades there’s an ever increasing number of young people playing lyra, lute, mandolin – it’s crazy! However, especially during the last decade, and perhaps because Cretans feel that they are being culturally besieged by fundamentally different ways of life, Cretan music has become self-referential. While thousands of youngsters are playing and singing it, Cretan music became very extroverted, very masculine, it lost its female element, its introspectiveness and diversity.

In the last couple of decades there’s an ever increasing number of young people playing lyra, lute, mandolin – it’s crazy! However, especially during the last decade, and perhaps because Cretans feel that they are being culturally besieged by fundamentally different ways of life, Cretan music has become self-referential. While thousands of youngsters are playing and singing it, Cretan music became very extroverted, very masculine, it lost its female element, its introspectiveness and diversity.

So, you are saying that Cretan traditional music has been homogenized.

Yes, it has been homogenized and standardized. This “return to tradition” that everyone welcomes with joy is not a return to self-reflection. It is a chauvinistic, narcissistic return; I believe in what the poetess Katerina Gogou said, that “our roots are not there for us to return to them, but so that we can grow branches”. I would add that tradition has deep roots in a specific time-space, so that its branches can potentially spread across multiple places and times. Also, I believe that tradition is what can be paired to something else. The sterile, obsolete version of tradition that is displayed as an exhibit in a folklore museum is doomed to perish. In reality, what remains of tradition is only what is necessary, and the necessary is always a product of composition; and composition could never contain similar things. Good compositions are made from something that we consider our own, and something that we consider foreign, things that are opposed but yet complementary.

There is, however, something special about Crete that relates to why this very old music is still being played, isn’t there?

Yes, of course there is. Crete is one of the last quasi-closed societies. Why? First of all, because it is surrounded by sea, and therefore has a very definite geographical boundary, and secondly, on account of the land: Crete has three huge mountain ranges, with hundreds of peaks over two thousand metres high, and an impressive biodiversity, ranging from chestnut trees to palm trees. This gives the island self-sufficiency in food, but at the same time, an extremely uneven terrain. Due to this ruggedness of the land, always interrupted by mountains, allotments in the lowlands have always been small, and since there were no large farming plots, there were no feudal lords, so Crete has been a relatively classless society. This anthropological and geographical uniqueness makes it one of the last places in Greece where the continuity of musical expression has never been interrupted.

And of course Crete has some amazing people. Look, Cretans are a war tribe in decline. So, in the absence of wars, they engage in displays of masculinity, in displays of wealth, in illegal activities and so on. But nevertheless, there are minorities of Cretans who are real poetic warriors. There are people with soul, with self-denial, amazing warriors and citizens, in the sense of assuming responsibility for all; with all the hospitality, the openness towards diversity, the eternal enthusiasm, the self-abnegation, all this wonderful graceful exaggeration. This is unique. Truly unique. But these are minorities, as they always were, only now these minorities are even smaller.

And of course Crete has some amazing people. Look, Cretans are a war tribe in decline. So, in the absence of wars, they engage in displays of masculinity, in displays of wealth, in illegal activities and so on. But nevertheless, there are minorities of Cretans who are real poetic warriors. There are people with soul, with self-denial, amazing warriors and citizens, in the sense of assuming responsibility for all; with all the hospitality, the openness towards diversity, the eternal enthusiasm, the self-abnegation, all this wonderful graceful exaggeration. This is unique. Truly unique. But these are minorities, as they always were, only now these minorities are even smaller.

What about the village Anogia in particular? It seems to produce an endless string of talented musicians.

I have collaborated with many musicians form Anogia. When I was learning Cretan music, several years ago, I played at weddings and festivals in Anogia, so I have played with Psarogiannis Xylouris, brother of Nikos Xylouris and the best lute player in Crete – along with Markogiannis. I’ve also been collaborating in albums and performances with Psarantonis for 15 years. Psarantonis is the greatest lyra player alive now, he is a narrative gravitational centre, he lives like a lyra player should. Quite a unique person.

I have worked with many other musicians from Anogia as well. It is a very beautiful village, people have a special sense humour, are quick-witted and they support each other, they have strong social bonds. For example, when a new lyra player makes his first appearance, half the village will show up to support him. They have a strong sense of solidarity. However, Anogia, like Crete itself, is not excluded from the nationwide and global decline. Do not forget that at this point in time, the entire world, from Western liberal democracies to Arabic theocratic regimes, lacks meaning. Right now there is no vision in the world. People cannot dedicate their actions. They cannot give meaning to existence. What kind of vision for the future do we offer young people? Most suggest trying to find a job to make money, but that is not a vision. That is the common meal of the prisoner. So the world is at an existential impasse. Neither Crete nor Greece can be excluded from that.

“The Tiger” (2000), Lyrics & Music: Dimitris Apostolakis, First version: Psarantonis: “I have a ravenous tiger within me which always waits for me and I for her, I hate her and she hates me, and she wants to kill me but i hope that she will become friendly with time. She has her teeth on my heart, her claws on my mind and for my own sake I fight for her And she makes me hate all the good things in this world so that i can sing to her with the deepest of sorrows. She forces me to cross mountains, valleys and chasms in order to embrace her in the wildest of dances, And when, at cold nights, she remembers her cages she lends me her pelt to wear. And when sometimes we lie drunk, almost in peace, so that each one can sleep, this still silence is like the one before the storm, like the final moment before she attacks.”

You mentioned living “like a lyra player”. What is the role of the lyra player in Cretan music? How does the concept of ‘parea’ (gathering) and revel fit in the whole picture?

There are tons of lyra players around, but no one lives like a lyra player. No one expresses the objective of their role, which is to be a narrative centre of gravity. Something similar to what bards-narrators of Homeric epics were; in ancient Greece, there were thousands of them, wandering from place to place and narrating the epics while playing their instrument. Later on, the bard-narrator became a lyra player in Crete, and the lyra player became a rapper in New York.

Now, this narrative centre of gravity is basically lost. And along with it we lost the ring, the turf were musicians would play out their role. In the older days in Crete, the lyra player sat in the middle and the people around him danced. The lyrics (mantinades) were improvised, in a give-and-take between musicians and dancers, it was a whole theatrical undertaking. Now the lyra player is up on stage, separated from the people dancing below. The whole of Europe is plagued by the death of ceremonies, big and small. Christmas for example, was the celebration of nature’s new seed and was associated with the passage of time, but at the same time many people -consciously or unconsciously- were swept away by the river of the ceremony, experiencing the joy and deep mourning at the same time.

Of course ‘parees’ are still going strong, you can see “parees” forming spontaneously and they are often more successful than organized festivals. For example, in October during “rakokazana” celebrations, all hell breaks loose. But I rarely go to these things anymore; I miss this sacred weight of mourning. Up until some decades ago in these ceremonies, celebration was intertwined with mourning, birth with death, yin with yang, creation with destruction. The joy did not emerge from the prosperity and the abundance of meat and cakes. It was basically borne out of frugality, and the fact that everyone was present in the celebration, all the living along with all the dead and all the unborn. Joy sprung as flowers grow from dung, it came through death. And the people who took part in these celebrations were like sacred dancers balancing on the rope between the tragic and the ridiculous – a sacred intermediary between the primitive and the divine. This is lost now. Revels have lost their ancient, eternal weight, and therefore have lost their lyra player – Hierophant.

Lyra players no longer improvise, they play with a kind of exaggerated high energy that says we are here, we are the best men, our land is the best, so there is not room for anything else; in essence the whole thing becomes self-indulgent. Of course there are resistances. Crete is an amazing place. Even by imitating ceremonies, at some point, some people may manage to create actual ceremonies. I believe that with so many young people playing music today, something new will be born; something will spring up. At all times and places around the world, anything of beauty, spiritual works or artistic creations, have been products of a small but grand ‘holy minority’, as Shelley called it.

How has Erotokritos, the romance poem composed by Vitsentzos Kornaros in early 17th century Crete, influenced Cretan music and lyrics?

How has Erotokritos, the romance poem composed by Vitsentzos Kornaros in early 17th century Crete, influenced Cretan music and lyrics?

Erotokritos, up until recently, played the role that Homeric epics played in antiquity. This means that people knew Erotokritos by heart and sang it in gatherings, while doing agricultural work, when they were alone and felt longing, and everyone had a particular passage they liked. Lines from Erotokritos were also used as maxims, proverbs and generally the poem served as a value system. Just like the Homeric epics valued beauty, bravery, and honour, Erotokritos valued beauty, courage and wisdom.

Moreover, these poems share another distinctiveness, in that just as the Homeric epics in ancient Greece sustained the Greek language during the so-called ‘dark centuries’, Erotokritos passed the language to the newly established Greek state. For a language to be spoken it must be realized poetically and epically. This is the method of the epics. We should not forget what Borges said, that the highest kind of literature is poetry and the highest kind of poetry is the epic, because, like he said, only in an epic poem can a happy ending be justified. Erotokritos was the basic living manual of every Cretan, every shepherd in his sheepfold had a copy of Erotokritos.

Psarantonis and I learnt Erotokritos from the oral tradition. We are the its last narrators and we had the pleasure of presenting it in a performance with the group Hainides, many musicians, as well as the exceptional modern dance and acrobatics team “And yet it is moving.” So I learnt this poem from listening to people reciting it; it is the last epic poem in Europe that up to at least 20 years ago was being sung by the people. For example, Nibelungenlied, the German epic poem, has not been sung for ages. That is what Erotokritos was and its function in Crete. It incorporated all of popular wisdom and was thus embraced by ordinary people.

*Interview by Ioulia Livaditi

Erotokritos – The Dreary Tidings: Lyrics

TAGS: MUSIC