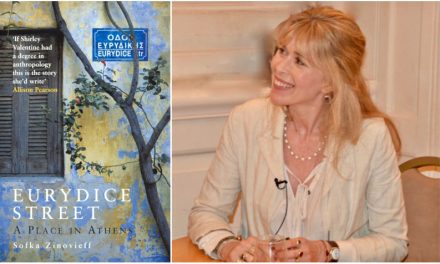

Eleana Ziakou graduated from the Department of International and European Studies of Panteion University and the Department of Literature and Albanian Language of the University of Tirana. She holds a Master’s degree in Environmental and Energy Law from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and a Master’s degree in Theatre Pedagogy from the Open University of Cyprus.

Since 2009 she lives in Brussels and is also active in the field of cultural journalism and literary translation from Albanian to Greek and vice versa. Her first poetry collection is soon to be published in Greek by Saixpirikon.

How did your involvement with literary translation begin? Which continues to be your driving force?

My initial involvement with translation on an amateur level dates back to the time I was a high school student in Albania, when the neighbours in my apartment building asked me to translate the Greek subtitles into Albanian whenever Latin American soap operas were broadcast on the Greek satellite channels. Their obsession was so great, to the point that they often asked my teacher for permission when the broadcast times coincided with those of my courses. Although Greek is my mother tongue and the language of my family, I did not have the opportunity, like the other Greek children living in the Greek-speaking villages of Albania, to attend primary school in Greek. I owe the learning of reading and writing in Greek at the age of six or seven mainly to my grandfather and less to my parents. However, oral Greek has always been an integral part of my linguistic formation and I never cut the umbilical cord with my Greek identity.

My first professional experience was during my internship at the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the Department of South-Eastern European Countries (2007-2008), where I translated the Albanian press into Greek. Before 2013, mainly due to a busy study schedule in three different countries, I did not have the chance to seriously engage in literary translation. Once I settled in Greece and after many years in Belgium, I had to deepen my linguistic knowledge simultaneously in Albanian, Greek and English within twelve years. Perhaps for these reasons I entered the literary translation field quite late.

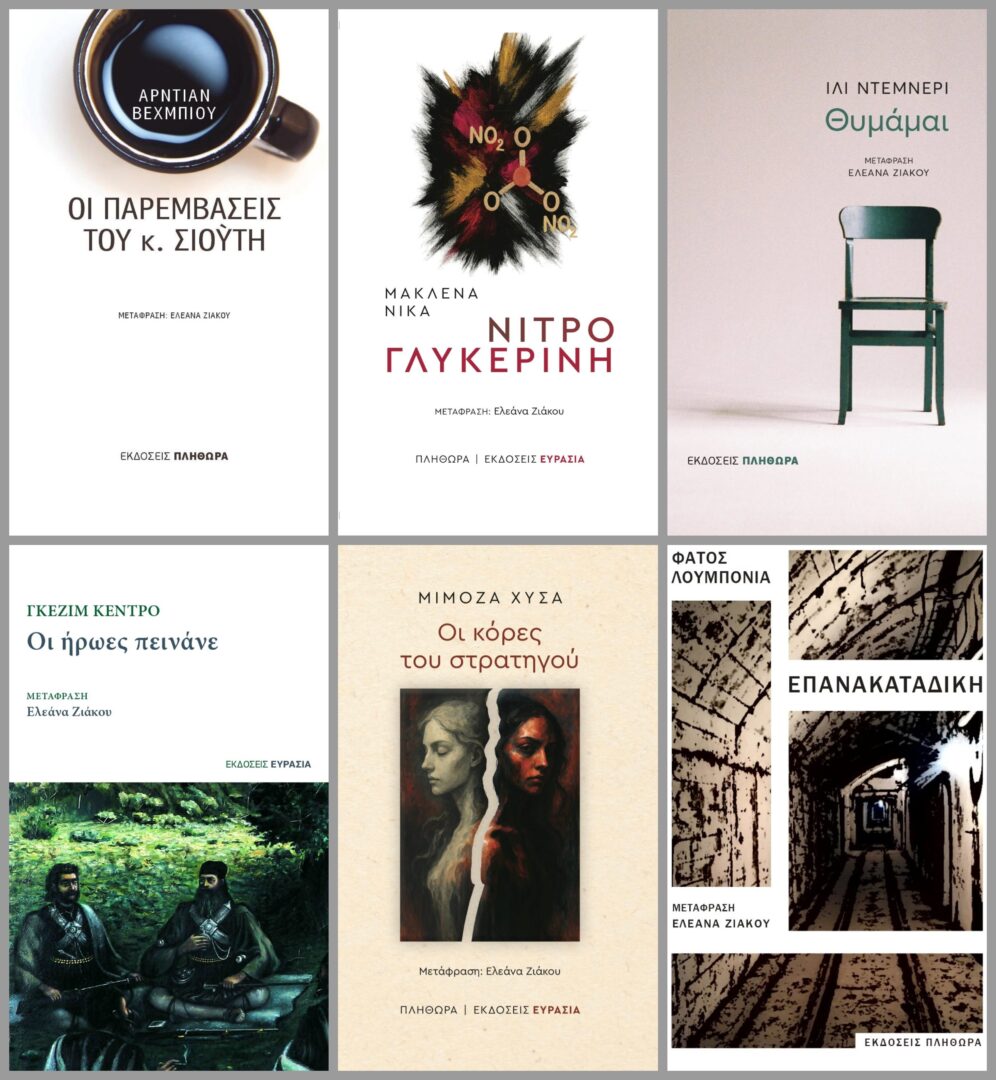

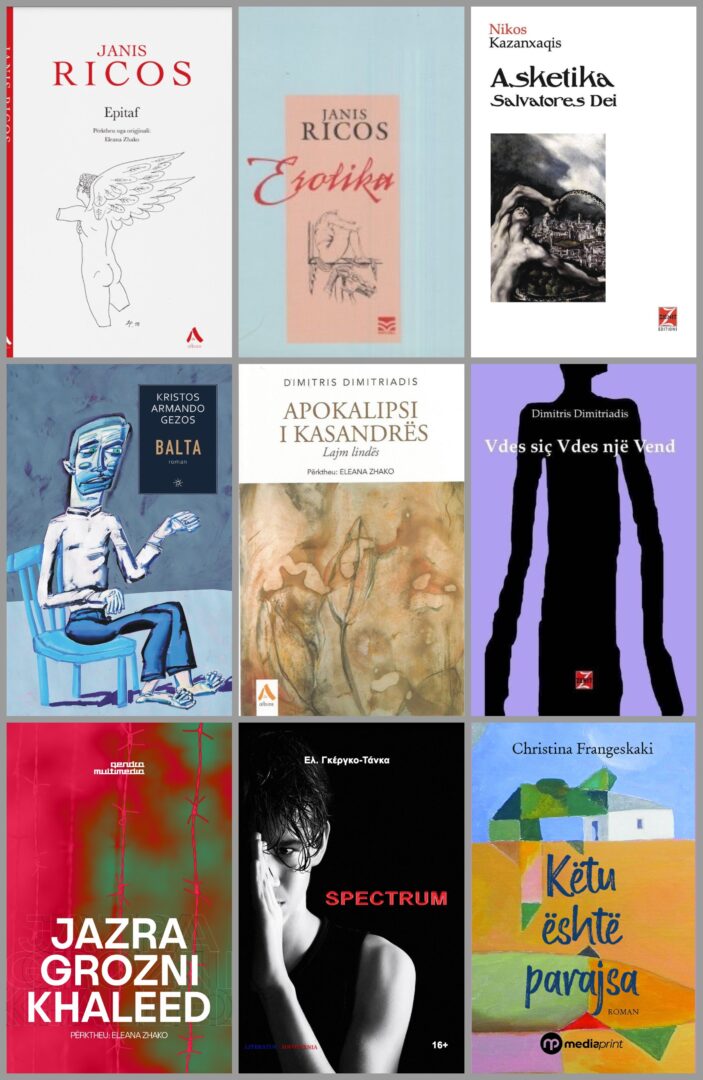

My first literary translation came completely out of the blue, and certainly not after prior thought and research. Dying as a country by Dimitris Dimitriadis is the first book I translated into Albanian. Due to the difficult nature of the book, I made a bet with my former supervisor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs whether I would succeed and after 1.5 years, in the midst of childbirth and after the birth of my daughter, I was able to complete the translation and set sail for its publication. Many translations of Greek and Albanian authors into both languages followed. Love for literature and languages is my driving force. Every time I want to break this deeply complicated relationship with translation, the wave rises and drags me into the vast sea of literature.

Being a translator of Greek literature in Albanian and vice versa, which have been the major challenges you have been faced with?

When working in two linguistic fields, serving the literatures of both countries, the main difficulties are related to the interaction of the two languages in the translation process and the difficult task to identify the Albanian linguistic interference into the Greek language and vice versa. The Greek language, due to its longer written tradition and the continuous close interrelation between ancient, Byzantine Greek, ‘katharevousa’ and the demotic language, carries more substrates than the Albanian language, sometimes making the translation work more demanding. Of course, the challenges in both languages are inherent to the nature of the task the translator is called upon to carry out. In poetry, and especially in metrical poetry, the difficulties are evenly balanced and the richness of a language is estimated quite distinctively compared to other fields.

As for translation challenges on a personal level, the impact on the Albanian language was greater, because some of the Greek writers I chose to bring into Albanian, such as Ritsos and Kazantzakis, are major names in domestic and world literature, so their works could not go unnoticed. Nevertheless, other writers I have translated, such as Dimitris Dimitriadis, Christos Armando Gezos and Christina Frageskaki, have enjoyed considerable success with Albanian readers. The difficulties of each translation vary, but Dimitriadis’ Dying as a country and Cassandra’s Annunciation, Gezos’ The Mud and Ritsos’ Epitaphios have been in a way a school of translation for me. Both Dimitriadis’ Dying as a country and Gezos’ The Mud consist of extremely long, high-density sentences with very few punctuation marks, which is not so common in Albanian literature. As for Ritsos’ Epitaphios, which is written in decapentasyllabic verse, the Albanian translation was quite demanding since I had to sacrifice either meter or rhyme; I chose the middle way, preserving Ritsos’ lyricism.

I have experienced similar difficulties in my Greek translations, which so far include seven books by Albanian writers published by Eurasia, one by Literatus Publications, two small poetry anthologies by Teflon Magazine and two important bilingual editions by the Centre for Albanian Diaspora. I will mainly focus on the latest translation of Maklena Nika’s poetry collection Nitroglycerin, which was recently published and presented at the Thessaloniki Book Fair. Due to the particular medical vocabulary used by the poet, I had to maintain the intricate balance between poetry and medical terms, not at all easy to achieve. In addition, the historical and artistic essay “Heroes are Hungry” by Gezim Qendro (Eurasia Publications), presented translation difficulties related to the essay’s language. I believe that my university studies at Panteion University helped me in this direction.

What is that make Greek literature appealing to Albanian readers, and, vice versa, in what ways does Albanian literature attract the interest of a Greek audience?

The long-lasting interest of Albanian readers in Greek literature is mainly due to the universality of Greek literature, i.e. its well-known authors, ancient and not, who have left their indelible mark on the course of world literature. As is the case in other foreign countries as well, it is mainly the global and international Greek writers who offer modern Greek literature its contemporary prestige. In the case of Albanian literature, the path that leads to Greek readers is harder to reach, due to the reduced interest in regional literatures and especially in Balkan literature.

The prominence of some Balkan writers in Greece, whether older or contemporary, is a result of the international fame they have achieved; a case in point is the famous Albanian writer Ismail Kadare. Nevertheless, it is rumoured that after the mass arrival of Albanians in Greece, Kadare’s popularity experienced a significant decline, which means that sometimes literature is also defined by geopolitical factors and trends change. Although there have been plenty of Albanian writers translated into Greek, both prose writers and poets, the question is whether Greek readers are aware of any contemporary Albanian writer, or even older, apart from Kadare.

Last year the poetry collection Child of nature (Plethora – Euroasia Publications, 2024) by the internationally renowned Albanian poet Luljeta Lleshanaku, translated by Andrea Zarballa, was published, and went completely unnoticed. In addition, the book Second Sentence (Plethora – Euroasia, 2022) by the well-known Albanian intellectual and writer Fatos Lubonja, which narrates his experience of his long-term imprisonment in the political camps of the communist regime, did not attract the interest of Greek journalists, political scientists and the reading public in general. The same book has enjoyed considerable success in the United Kingdom. It seems pessimistic, but the reduced impact should not discourage the translation of literature from the neighbouring country, even if only a few readers benefit from it.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

I was confronted with this dilemma in my first official translation into Greek of the book The interventions of Mr. Shyti (Plethora-Euroasia Publications, 2018) by Ardian Vehbiu. When the book was published and posted it on the social media, I remember a comment made by a well-known translator of Bukowski in Albanian with a good knowledge of the Greek language, which wondered why I chose not to follow the grammatical rules related to the transcription of foreign surnames. She thought it was a trick to the Greek reader so that I could hide the non-Greek origin of the protagonist in the title. I replied that since the same surname is found in both countries and the translation is intended for the Greek reader, there was no reason to identify Mr. Shyti on ethnic grounds. After all, the name of the author and the inclusion of the book in the category of translated books spoke for themselves of the “foreign element”. Although the book belongs to the literary genre because the author is a well-known linguist in Albania, it is distinguished by an abundance of linguistic puns and proverbial phraseology. If Fatlum, one of the characters in his nano-stories, had remained Fatlum in Greek, it would have retained its original form, but the reader would not have understood the author’s ironic choice, which in Greek is ‘Καλομοίρης’ [’ fortunate’ in Greek].

For this kind of issues, names and appellations, various slang words and proverbs with vulgar nuances, I found refuge in footnotes; yet, I did not want to burden the reader with too many explanations, which would make reading tedious. So, I sacrificed some things from the original for the sake of better understanding. This is just one case because in too many of my translations into both languages, I had to be more creative, culminating in the translation of Dimitris Dimitriadis’ Cassandra’s Annunciation, whose text was full of word formations and I had to invent something similar in Albanian.

I consider that a translation can be unethical when translators do their ‘stunts’ without exhausting all other means, when the various changes they make are not for the benefit of the author, but for their thirst for self-reward and originality, feeling that they are the exclusive, intellectual property owners of the translated work.

Would you say that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value, or is translation inextricably linked to its surrounding socio-political and cultural environment?

I would say it is both, given that translation is an autonomous act that strives to be independent of its original context, and acquire its own artistic and aesthetic value regardless of time. It is no coincidence that many translations, despite having been made under completely different socio-political and cultural conditions, retain their immediacy and timelessness. Clearly, translation is a product of the socio-political environment to which we belong in the present as well as that to which we belonged in the past. Had I not spent many years in Athens – considering not so much my studies as my everyday life, the contact with people from all social strata, the daily vocabulary – it would have been impossible for me to translate into Greek. It is very important for the translator to have a practical knowledge of the language of the country or countries he or she is translating and not just through schooling and books. However, there are projects where an experiential knowledge of current affairs and domestic reality is a prerequisite for the successful completion of a translation.

How important is the role of translation in the dissemination of a literature beyond national borders? In general, could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries;

Translated literature can significantly contribute to a better understanding of different cultures, as well as to a deeper perception of a country’s inhabitants of their own country. Yet, how many readers in today’s world are inspired by literary works to delve deep into the culture of another country? Most people move through tourist guides and their stimuli are mainly fed by digital and television images.

In an earlier collaboration with French photographer Michel Setboun, he told me that one of the main reasons he wanted to visit communist Albania in the early 1980s was to see the country described in Ismail Kadare’s book The general of the dead army. Kadare became widely known in France in the 1980s since he was translated into French at a time when the borders of communist Albania were tightly closed and no one could travel outside the country, with very few exceptions. Its translator was the French-speaking Jusuf Vrioni, a descendant of a large family of landowners and a former political prisoner in Hoxha prison. After his release from prison, he worked on translating Enver Hoxha’s political texts and Ismail Kadare’s books into French. If Kadare had not been published in French, which formed the basis for his translation into other languages including Greek, his fame would probably not have gone beyond the borders of national literature. Kadare’s case is worth mentioning because it demonstrates the mediating and decisive role of the translator as an ambassador of cultural values under conditions of political stifling.

Translators are the invisible hand that ensures the perpetuation of the author’s name and work beyond national borders. A world without translators would resemble the setting of the Tower of Babel, doomed to incoherence.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE