In the context of the 2020 “Year of Melina Mercouri” and the vision for the reunification of the Parthenon sculptures

By Dr. Alexandra Kouroutaki

Alexandra Kouroutaki is a member of the Laboratory teaching staff (EDIP) at the School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete. She holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, a Postgraduate Diploma in French Literature from the School of Humanities of the Hellenic Open University, and is an honors graduate of the Department of French Language and Literature of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

What sorrow it would have been – my God –

what sorrow

if my heart was not consoled

by the hope of marbles

and the prospect of a bright sunray

which shall give new life

to the splendid ruins[1]

Nikos Engonopoulos

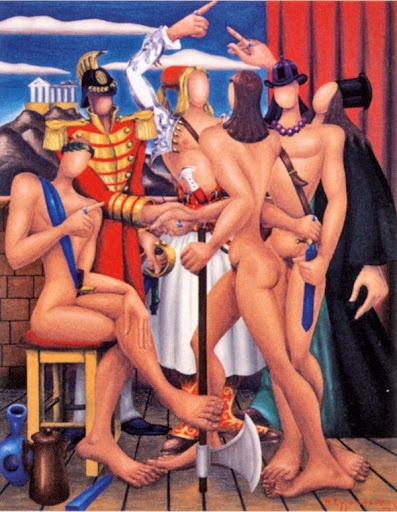

Nikos Engonopoulos, The oath of members of the Society of Friends, 1952, oil on canvas, Municipal art gallery of Rhodes

Introduction

A diachronic symbol of Hellenism and the fundamental principles and values of European civilization, the Parthenon is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This essay endeavors a study of the Parthenon, which is present as a symbol in modern Greek art, both in landscape paintings of the early 20th century as well as in artworks of the interwar years, in compositions with historical and mythological-allegorical subject matter, in portraits and still lives.

In the first part of the study, the focus is on landscape paintings of the 1910-1930 period that have the Acropolis as their subject matter and the direct, dialectical relationship between the Parthenon and the Attic landscape is explored. The sight of the monument gives Greek artists the opportunity to capture in their paintings the “spirit of the place” that inhabits these rocks, the hills, the natural qualities of the landscape, the curves on the ground, the brightness of the natural Mediterranean light and the blue of the sky. Here, in the natural setting which shaped this aesthetic model, the building blocks of the monument, the marbles, converse with history.

In the second part, the study focuses on paintings produced in the interwar years. Compositions of the celebrated “Generation of the ‘30s” in whose depictions the Parthenon functions as a symbol of national as well as world heritage are examined. The Monument on the one hand becomes the mirror of the cultural consciousness of the Greek nation, whilst it is also inextricably linked with a broader symbolism that includes the ideals of Athenian democracy, the achievements of rationalism and dialectical philosophy as well as humanitarian values.

Apart from the symbolic function of the Monument however, the study aims to highlight the ideological background of the pursuits of Modern Greek art, according to the historical context and broader developments in arts. In particular, emphasis is given on the Greek transformations of Modernism. There is reference to the influences of Symbolism and Post-Impressionism in early 20th century landscape paintings and to the influences of Cubism and Surrealism on works by important artists of the interwar generation.

1. The Parthenon in landscape paintings and the unbreakable unity between the Monument and the Attic landscape

At the beginning of the 20th century, landscape painting was the major event in the development of Modern Greek art, pointing to new directions[2]. Innovative Greek landscape painters moved away from conventional representation, releasing themselves from the mainstream aesthetics of Academic Realism of the Munich school. Their interest at that point turned to the pioneers of Modernism and the avant-garde movements of Paris[3].

The historical and political context in Greece was favorable to this development. The policies of Venizelos contributed decisively to the reorientation of the Greek intelligentsia towards European Modernism. In 1917, and in the spirit of “Venizelismos” that was associated with the need for modernization and the cultural and civic regeneration of the Greek state, the “Art Group” (Omada Technis) was established with the purpose of transplanting new ideas onto the conservative Greek artistic landscape[4].

Landscape painting in the years 1915-1930 was astonishingly uniform. It was a post-impressionist, subjective art[5], with several influences from Symbolism. Important Greek artists of this generation, who were members of the “Art Group” such as Konstantinos Parthenis, Konstantinos Maleas, Nikolaos Lytras, Periklis Vyzantios, Nikolaos Othonaios, Othon Pervolarakis, Lykourgos Kogevinas, as well as Michael Economou and Spyros Papaloukas, approached landscape portrayal insightfully, investing it with symbolic dimensions. M. Stefanidis points to this evolution in Greek painting towards subjectivism: “One could say that our artists are dazzled by their discovery of the landscape, its energy, the uniqueness of the bright summers and the strict contours of the mountains … and approach it in an exploratory and insightful way[6]“.

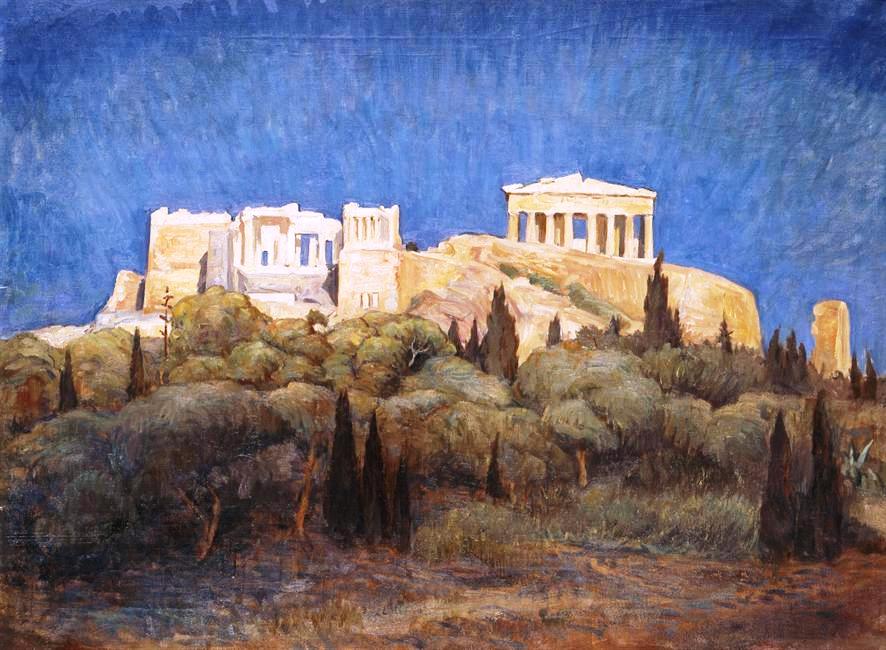

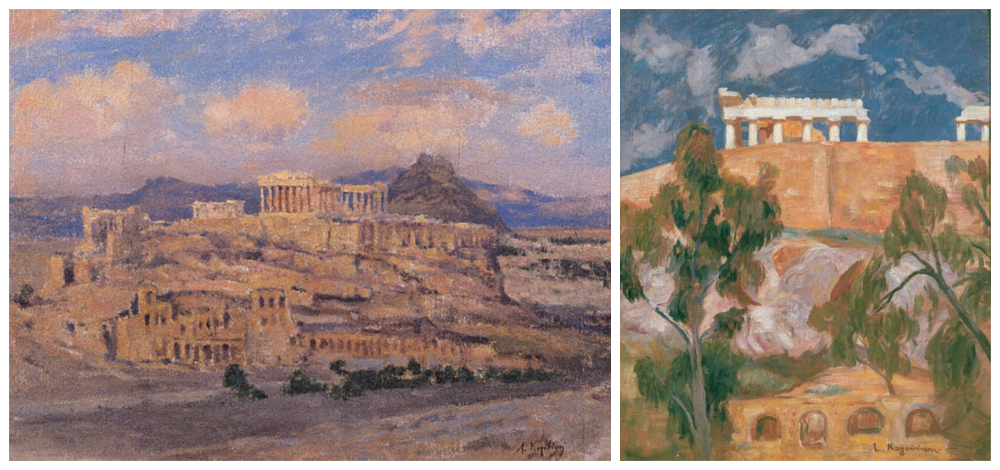

Fig. 1. Kogevinas (1887-1940), Acropolis, Oil on canvas, National Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

Fig. 1. Kogevinas (1887-1940), Acropolis, Oil on canvas, National Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

Subjectivism in landscape imagery and the tendency towards symbolism characterise the oil paintings of the Acropolis and the Parthenon by Lykourgos Kogevinas. His landscapes (figs. 1, 2) observe the principles of anti-naturalistic representation, as indicated by the flat portrayals, the shaping of surfaces and the general rendering of natural elements. The solid masses, in their immobility, bear witness to the influences of P. Gauguin and M. Denis[7]. In any case, we must underline the impression made by these landscapes. The prevailing feeling is that we are not just seeing an accurate representation of a natural or structured space but a Monument that’s a symbol. The theatrical, anti-realistic lighting connects the Parthenon with its unique cultural burden and renders life to the memory of the eternal Mediterranean light.

Fig. 2. Lykourgos Kogevinas (1887-1940), Acropolis, oil on canvas, Averoff Museum; Fig. 3. Lykourgos Kogevinas (1887-1940), Parthenon, oil on canvas, Averoff Museum

Fig. 2. Lykourgos Kogevinas (1887-1940), Acropolis, oil on canvas, Averoff Museum; Fig. 3. Lykourgos Kogevinas (1887-1940), Parthenon, oil on canvas, Averoff Museum

We get the same feeling of the symbolic function of the monument in the landscape paintings of Konstantinos Maleas (figs. 4, 5) of the Acropolis. In the landscape background, the Monument’s shapes are rendered austerely and abstractly, under the blue or golden sky of Athens. In the foreground, we can see the dense vegetation of the region which consists mainly of pine and cypress trees. All the elements of the composition, the monument, the rocks, the trees, the ground and the sky are stylised, with flat colors on the surface[8]. Antonis Kotidis points to the influence of the French painters Gauguin and Bernard on the aesthetics of Maleas’s landscapes and notes the influence of Symbolism in the subjective rendering of nature and the “correspondence” (according to Baudelaire) between colors and emotions, in path lines and the development of musical phrases.

In conclusion, the landscapes of the innovative painters of the “Art Group” depict the Parthenon as a symbol, emphasizing its inseparable unity with the Attic landscape. This unity is pointed out and invoked by Le Corbusier, in a 1933 lecture, stating characteristically: “The Acropolis made me a rebel. This belief has remained with me. Remember the Parthenon pure, clean, intense and bursting with a superior economy. This cry that erupted in a landscape full of joy and terror. Strength and purity[9]“.

Fig. 4. Konstantinos Maleas (1879-1928), Acropolis, oil painting 1918-1920

Fig. 4. Konstantinos Maleas (1879-1928), Acropolis, oil painting 1918-1920

Fig. 5. Konstantinos Maleas (1879-1928), Acropolis, oil painting 1918-1920

Fig. 5. Konstantinos Maleas (1879-1928), Acropolis, oil painting 1918-1920

One hundred years after it was founded, the “Art Group” continues to arouse the interest of scholars and art lovers as it was identified with the beginnings of Modernity in modern Greek art. It was a Greek Modernism that looked for global characteristics[10]. However, in the mid-20s, the demand for a move towards tradition gained strength, giving a new twist to the Greek version of Modernity. The “Art Group”, and Parthenis especially, had prepared the ground for the appearance of the painters of the legendary “Generation of the ’30s”, a generation that produced works with greater ethnocentric ideology[11].

2. The Parthenon in the realm of “Greekness” and the artistic “Generation of the 30’s”

Important modern Greek artists of the interwar generation, such as Gerasimos Steris, Giorgos Gounaropoulos, Konstantinos Parthenis, Nikos Engonopoulos and Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, created paintings in which the Parthenon is depicted as a symbol of the Greek spirit and a universal symbol of civilisation. In the interwar years, artistic creation in Greece entered a new phase, between Modernism and Tradition[12]. The turn to Tradition became imperative following the traumatic experience of the Asia Minor Catastrophe that created the need for national self-affirmation, which was also expressed in the arts. The “Generation of the ’30s”, known as the most characteristic wave of Modernism in Greece, created an art with an ethnocentric ideology whose central tenet was the quest for “Greekness”, while at the same time it adopted and assimilated creative elements of the European artistic avant-garde.

The case of Gerasimos Steris is indicative of the developments that took place in Modern Greek art in the course of the interwar years. He introduced significant change in Greek painting by way of his abstract forms and the freedom of his painting style, together with its symbolic and metaphysical extensions. In Landscape with the Acropolis (fig. 6) the idealistic character of the composition is intensified by the progressive elimination of color and decorative logic of the design. Once again, the Monument that dominates the sacred rock, functions as a symbol that “shapes” the ideal.

Fig. 6. Gerasimos Steris (1898-1987), Landscape with the Acropolis, 1931-1935, Oil on canvas, National Gallery –Alexandos Soutzos Museum

Fig. 6. Gerasimos Steris (1898-1987), Landscape with the Acropolis, 1931-1935, Oil on canvas, National Gallery –Alexandos Soutzos Museum

The influence of Symbolism in Greek art is also found in paintings with mythological and allegorical subject matter. In 1938, Giorgos Gounaropoulos painted a mural in oil and wax covering a total area of 113 m² in the grand chamber of the Athens City Hall where the Municipal Council met (figs. 8, 9)[13]. The mural is a micro-historical composition[14] depicting various episodes from the mythology and history of the city of Athens, such as Athena’s dispute with Poseidon over the name of the city, the struggle of Theseus with the Minotaur, Aegeas waiting for the return of his son Theseus’s ship from Crete, Socrates drinking the poison, the naval battle of Salamis, the Persian wars, and the scene of the death of Georgios Karaiskakis, a hero of the Greek war of independence[15].

In the central scene of the mural, the Parthenon is depicted in the background, atop the sacred rock of the Acropolis. The figure of Pericles is rendered idealistically and spiritually (fig. 7). He is the charismatic leader of the “golden age” of Athenian democracy. The composition obviously aims at connecting the Monument with the ideals of democracy.

Fig. 7. Giorgos Gounaropoulos, The apotheosis of Pericles, Mural section, Oil and wax, 1938-1939. Old Town Hall, Athens

Fig. 7. Giorgos Gounaropoulos, The apotheosis of Pericles, Mural section, Oil and wax, 1938-1939. Old Town Hall, Athens

Fig. 8. Giorgos Gounaropoulos (1890 – 1977), The Struggle between Athena and Poseidon, mural, Oil and wax, 1938-1939. Athens Town Hall; Fig. 9. Athens City Hall. The municipal council chamber with the mural by Giorgos Gounaropoulos. Photo: Paris Tavitian, Lifo

Fig. 8. Giorgos Gounaropoulos (1890 – 1977), The Struggle between Athena and Poseidon, mural, Oil and wax, 1938-1939. Athens Town Hall; Fig. 9. Athens City Hall. The municipal council chamber with the mural by Giorgos Gounaropoulos. Photo: Paris Tavitian, Lifo

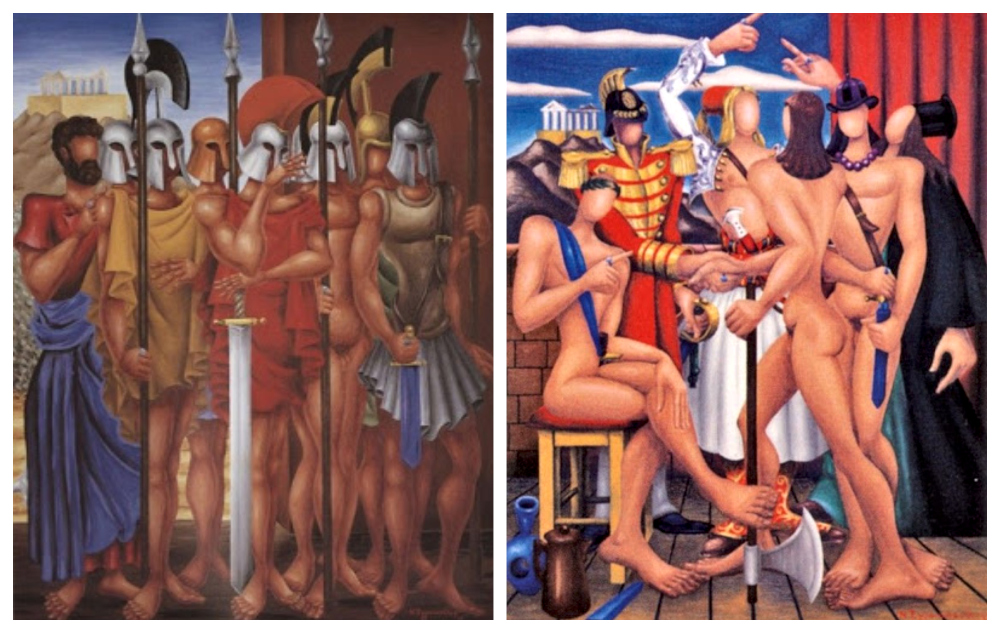

Also symbolic is the presence of the Acropolis and the Parthenon in the compositions of the poet and painter Nikos Engonopoulos, where Surrealism and metaphysical painting intertwined in a unique way (figs. 10, 11). Engonopoulos creates an anarchic montage of images, working with his imagination and memories. He creates theatrical scenes with his famous anthropomorphic mannequins (borrowed from Giorgio De Chirico) depicted either naked or dressed in vintage costumes. Engonopoulos’s enigmatic compositions are strewn with many diverse objects – symbols that refer to different periods of history, including antiquity, the medieval West, the Renaissance, but also Greek tradition and art. In the background of his compositions, Engonopoulos depicts the Acropolis in the Byzantine style. The Parthenon dominating the Acropolis functions as an allegorical bridge that connects modern Greece to its glorious past and at the same time highlights Greece’s intercultural relationship with the West.

Fig. 10. Engonopoulos Nikos, Alexander, Son of Philip, and the Greeks apart from the Spartans, oil painting, private collection, 1963; Fig. 11. Engonopoulos Nikos, The oath of members of the Society of Friends, 1952, Oil on canvas, Municipal Art Gallery of Rhodes

Fig. 10. Engonopoulos Nikos, Alexander, Son of Philip, and the Greeks apart from the Spartans, oil painting, private collection, 1963; Fig. 11. Engonopoulos Nikos, The oath of members of the Society of Friends, 1952, Oil on canvas, Municipal Art Gallery of Rhodes

Fig. 12. Yannis Moralis, By the outdoor photographer, 1934, oil in canvas; Fig. 13. Yannis Moralis: By the outdoor photographer (detail), oil on canvas, National Art Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

Fig. 12. Yannis Moralis, By the outdoor photographer, 1934, oil in canvas; Fig. 13. Yannis Moralis: By the outdoor photographer (detail), oil on canvas, National Art Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

The Parthenon is also depicted in a composition by Yannis Moralis with the title By the outdoor photographer (figs. 12, 13) emphasizing the special significance of the monument for the sense of national pride of modern Greeks, as confirmation of their cultural continuity. In this composition, the painter presents three portraits – of two women and a boy – as they are posing for a photo, outdoors. In the background lies the Acropolis, sketched abstractly, in simple lines. The relationship between the people and the monument is emphasised, as is the moral right of every people to enjoy the aesthetic perfection of their country’s monuments and to reconnect through them with their cultural heritage and tradition.

The Parthenon as a subject appears in the still life compositions of Konstantinos Parthenis (fig. 14), in a cerebral, spiritual, ideocratic and at the same time emotional art that employs elements from Cubism. The geometric rendering of the patterns takes place within recognisable frames of clarity. It should be noted that the morphology of Cubism does not prevent the artist from attempting to bestow a spiritual content to his painting and to express his philosophical perception of the world. The viewer is confronted with the spiritual meaning of the elements portrayed, while the artist attempts to transfer the “ideal” (Parthenon) to the realm of the human (still life).

Fig. 14. Konstantinos Parthenis, Still life with the Acropolis in the background, oil on canvas, before 1931, National Art Gallery Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

Fig. 14. Konstantinos Parthenis, Still life with the Acropolis in the background, oil on canvas, before 1931, National Art Gallery Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum

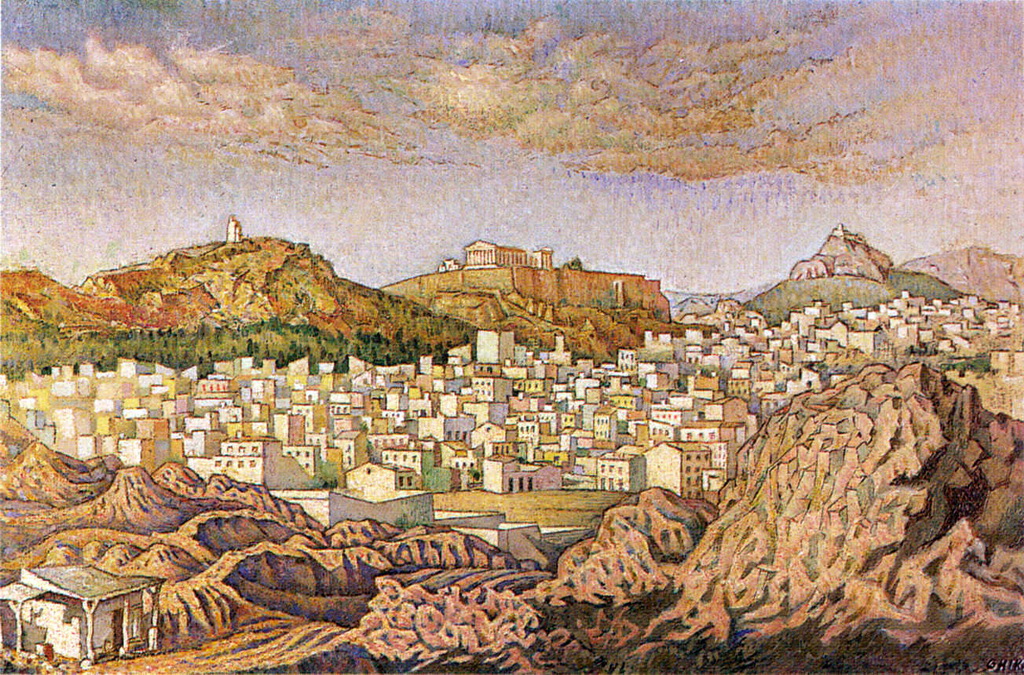

The presentation of the paintings depicting the Acropolis in Modern Greek art concludes with a composition by Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, View of Athens (fig. 15). With his particular Cubist style, Ghika depicts the three hills of Athens: the Acropolis, Lycabettus and Philopappos. The sacred Acropolis rock, the humble Greek homes, the golden light and nature are the ingredients that make up the Attic landscape. The Parthenon becomes the symbol of Athens, the bridge that unites the past to the present and future of the city.

Fig. 15. Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, View of Athens, 1940, oil painting, Private Collection

Fig. 15. Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, View of Athens, 1940, oil painting, Private Collection

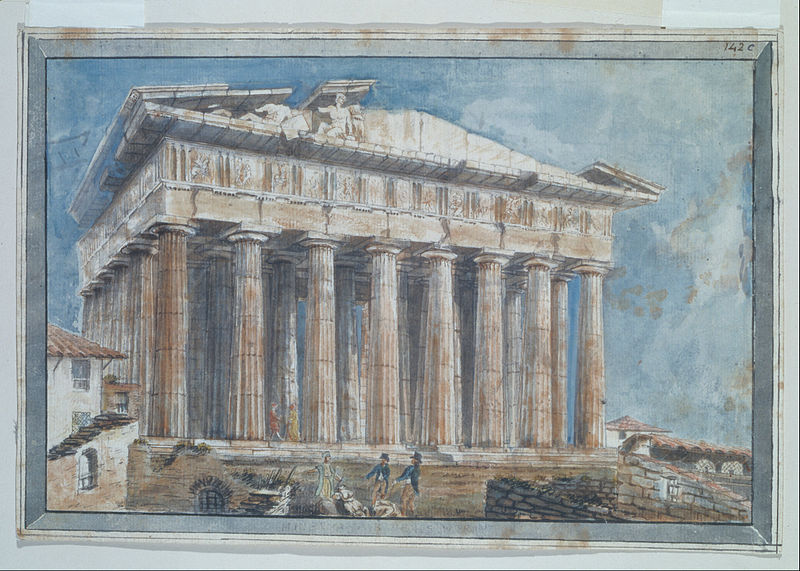

Fig. 16. Sir William Gell, The removal of the Sculptures from the Pediments of the Parthenon by Elgin, 1801, Watercolor on laid paper, Benaki Museum

Fig. 16. Sir William Gell, The removal of the Sculptures from the Pediments of the Parthenon by Elgin, 1801, Watercolor on laid paper, Benaki Museum

Epilogue

In conclusion, the Parthenon, which dominates the top of the Acropolis hill, often appears as a subject in the landscape paintings of the early 20th century, as well as in compositions with historical and mythological themes, still lives, even portraits. It functions as a landmark of our national identity and as an emblem of the Greek spirit, carrying the message of an enduring civilization, democracy, free-thinking and open society. Melina Mercouri’s words seem more applicable than ever: “This is what Greece is, its heritage and its wealth, and if we lose this, we are nothing.[16]“

Stylistically, Greek artists were undoubtedly influenced by developments in European art and the modernist movements. The compositions analysed in the present study highlight the profuse influences from Symbolism, Post-Impressionist painters, Surrealism, Cubism and Abstract art. Besides, these works were created in the general context of the emergence of a cultural vision where Greek art could coexist and converse on an equal basis with the West[17].

The Acropolis and the Parthenon stand out in Modern Greek art as symbols of national and world heritage. Greece’s call for the reunification of the sculptures of a Monument with universal symbolic value and unifying power is becoming universal. And this day will come soon, as the strong support from international public opinion indicates. The sculptures that were violently removed from the Parthenon (image 16) are not self-existent works of art. They form an indivisible, natural, aesthetic and semantic unit with the looted Monument and for this reason they should be reunited historically and aesthetically as one. The role of art in international awareness is important. The reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures is an ongoing European cultural and moral issue.

Translated by Marianna Varvarrigou and Magda Hatzopoulou

Read also via Greek News Agenda: 2020: Year of Melina Mercouri; Exploring the Acropolis #MuseumFromHome; The first photograph of the Acropolis and its history; Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Erotokritos’ intercultural substance and influence on Greek painting

[1] Engonopoulos, N., “Tram and Acropolis”, from the poetry collection Don’t talk to the driver (1938), Poems A’, Icarus, pp. 11-12.

[2] Kotidis, A., Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar period, University Studio Press, Thessaloniki, 1993, pp. 182, 192.

[3] Papanikolaou, M., Greek Art of the 20th Century, Paintings – Sculpture, Vanias, Thessaloniki, 2006, p. 49.

[4] Kouroutaki, A., “The beginnings of Modernity in modern Greek art in the spirit of ‘Venizelismos'”, Cretan Center, volume 15th, (2014-18) periodical edition of the Historical Folklore and Archaeological Society of Crete, Typokreta, Heraklion, 2018, p. 271.

[5] Kotidis, A., Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar period, op.cit., p. 182.

[6] Stefanidis, M., “Ellinomouseion, Seven centuries of Greek painting”, Vol. C. Light Engineers Free Press, 2009, p. 85.

[7] Kotidis, A., Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar period, op.cit., p. 182.

[8] Ibid, p. 196.

[9] Le Corbusier, «C’est l’Acropole qui a fait de moi un révolté. Cette certitude m’est demeurée: Souviens-toi du Parthénon, net, propre, intense, énorme, violent, de cette clameur lancée dans un paysage de grâce et de terreur. Force et pureté » dans « Air, son, lumière », conférence publiée dans les Annales techniques, 15 octobre-15 novembre 1933 (Le IVe Congrès international d’architecture moderne), Athènes, 1933, p.1140. See also Lucan J., «Athènes et Pise: deux modèles pour l’espace convexe du plan libre. Les cahiers de la recherche architecturale et urbaine: Le Corbusier, l’atelier intérieur », n. 22/23, 2008, p.66.

[10] Kouroutaki, A., “The beginnings of Modernity in modern Greek art in the spirit of ‘Venizelismos'”, op.cit., p. 271.

[11] Lambraki-Plaka, M., (ed.), 2001, “100 years National Gallery – Four centuries of Greek Painting”, from the Collections of the National Gallery and the Euripides Koutlidis Foundation. Athens: National Gallery and Museum of Alexandros Soutsos, pp. 122-123.

[12] Kotidis, A., Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar period, op.cit., p.15.

[13] Skaltsa M., Gounaropoulos, Cultural Center of the Municipality of Athens, Athens, 1990, p. 55.

[14] Kotidis, A., Modernism and tradition in Greek art of the interwar period, op.cit., p.118.

[15] Skaltsa M., Gounaropoulos, pp. 140, 141, 145 – 147 and Kotidis, A., op.cit., p.118.

[16] Melina Merkouri about the Parthenon Marbles, 2009. iPedia (2016) Melina Merkouri and the British museum director (YouTube).

[17] Kouroutaki, A., “The beginnings of Modernity in modern Greek art in the spirit of ‘Venizelismos'”, op.cit., p. 249.