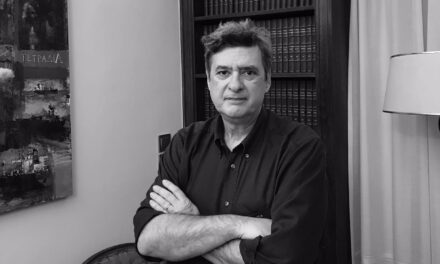

Christos Asteriou was born in 1971 in Athens. He studied German and Greek philology in Athens and Würzburg. He was head of the German department of the European Center for the Translation of Literature. Since 2008 he works in education. He has been teaching at the Chair of Modern Greek Studies in Freie Universität Berlin for the last four years. He was a literature scholar of the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin and the Fulbright Foundation at Columbia University. He has published one short story collection and three novels and has translated literary and philosophical texts from German. The therapy of memories (Polis, 2019) is his latest book.

Christos Asteriou spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book, which tells the story of Michalis Bouzianis, a renowned writer “confronted with a number of personal and professional crises”, a novel which “delves into issues such as humor, technology and political correctness”. As for the relation of literature to the world it inhabits, he comments that “there can be no literature outside the real world” given that “even good fantasy literature has a realistic background”.

Asked about the new generation of Greek writers and their potential to move beyond national borders, he notes that although “easy transports, the internet, the speed and easy of information, access to new titles of world literature have definitely influenced younger writers…there is observed a fixation to stories that have been heard a thousand times before as well as a reluctance to deal with contemporary issues”. He concludes that “there are many of [his] peers who write books that could easily stand at the international publishing market. What is required, however, is state support, as well as promotion and advertising mechanisms, which unfortunately are non-existent”.

Your latest writing venture The therapy of memories received rave reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The main character of the book Michael Bouzianis, a former stand-up comedian and now a renowned writer, is confronted with a number of personal and professional crises: an unexpected divorce, a writer’s block and his increasing alcohol addiction. During an event to commemorate 25 years since his first appearance in literature, he undergoes a panic attack and collapses before the audience. The book is divided in three parts: the first chronicles his fall, the second comprises parts of Bouzianis’ memoir titled “Notes on my life”, while the third part narrates the protagonist’s trip to Greece in an attempt to sieve through family secrets.

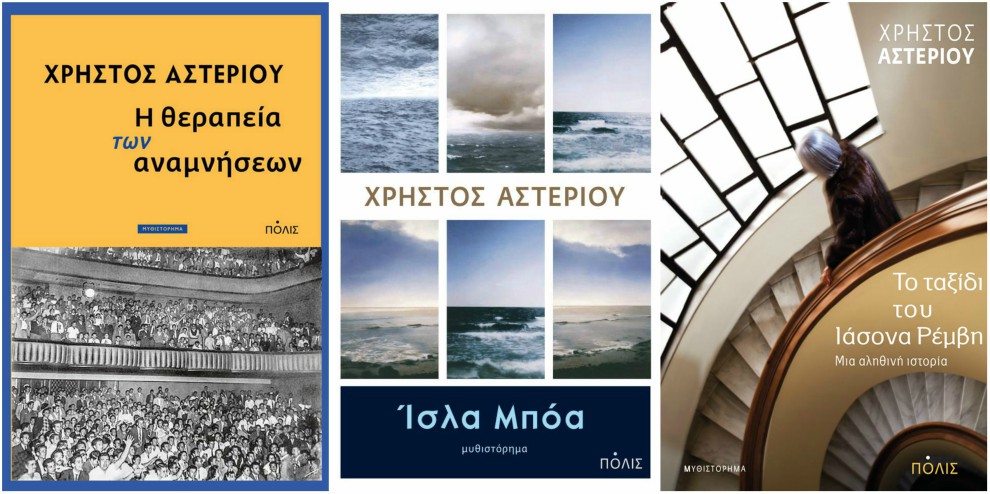

From The story of Jason Remvis in 2006 to Isla Boa in 2012 and The therapy of memories seven years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

My first two books belonged to fantasy literature. On the other hand, Isla Boa was a realistic novel with social and political connotations written prior to the crisis. The therapy of memories is a much more personal book which delves into issues such as humor, technology and political correctness. Undoubtedly there are ‘hobbyhorses’ and recurrent themes but I try not to analyze my books and detect specific traits.

What would you say is the relation of literature to the world it inhabits? Where does the world of fiction meet the real world in your writings? Are there auto-biographical elements in your books?

There can be no literature outside the real world. Even good fantasy literature has a realistic background. I draw inspiration for my books from my everyday life and my readings. There are auto-biographical elements in all my books. In The therapy of memories, for instance, I touch upon the thorny relationship I had with my father, yet I narrate it as something my main character experiences. This is usually the method I opt for: the invented myth is “stuffed” with numerous auto-biographical elements, which make it convincing.

“In a country like Greece where is art is considered a luxurious hobby, a writer is a person is who lays claim on even the last second in the unequal battle against the monster of the daily routine”. Τell us more.

In Greece, involvement in art is considered a noble hobby. As for literature, there is no interest whatsoever on the part of the state or private partners, which have focused their attention on other forms of art, mainly the theater, music and dancing. Greek writers are obliged to write on their spare time under quite adverse financial conditions.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

There is indeed a turn towards short form, which appears to attract readership as well. There is also a return to ethography with bucolic stories written in languages of past eras. Although I admit a genuine sensitivity in some of them, I opt from other types of books.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek writers is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. How do they relate to world literature? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

Easy transports, the internet, the speed and ease of information, access to new titles of world literature have definitely influenced younger writers. When my generation was making its first steps, everything arrived to us with delay. And yet, there is observed a fixation to stories that have been heard a thousand times before (the civil war, lost homelands etc) as well as a reluctance to deal with contemporary issues. Of course the local can become global; we have so many cases in point. On the other hand we must note that there are no limits and readymade recipes in art.

And, in turn, do Greek writers have the potential to move beyond national borders and attract foreign audiences?

What we lack in Greece are writers of worldwide caliber. We have no Saramago, nor a Claudio Magris, a Kundera, a Pamuk or a Javier Marias; that is a steam engine to pull the carriages forward and thus decisively determine the character of Greek fiction. Yet, we have major writers of an older generation as well as exceptional younger writers. There are many of my peers who write books that could easily stand at the international publishing market. What is required, however, is state support, as well as promotion and advertising mechanisms, which unfortunately are non-existent.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Zyranna Stoikou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE