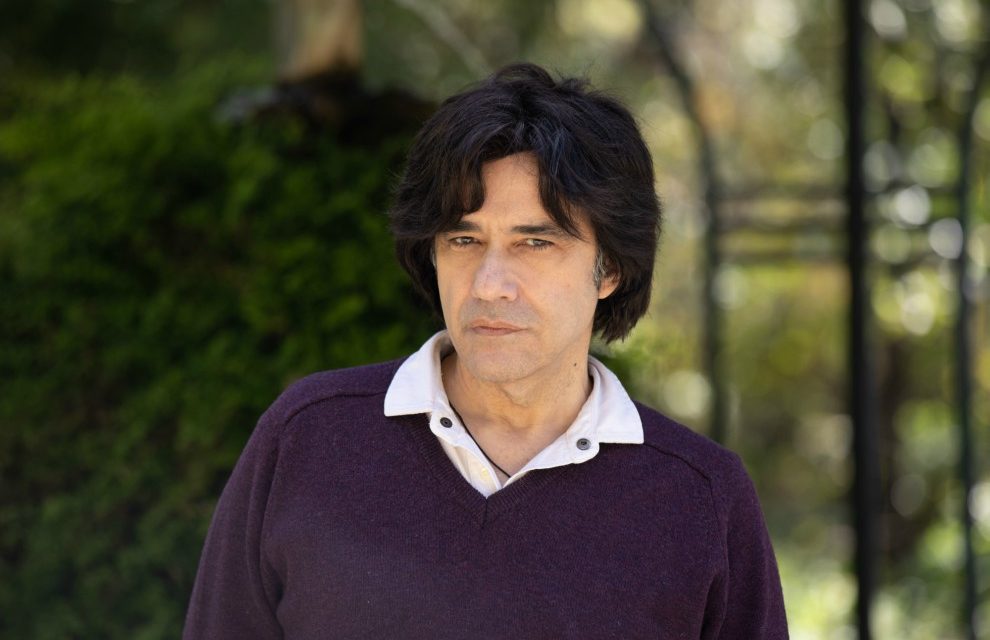

Alexis Stamatis was born in Athens. He studied Architecture at the National Technical University of Athens and received post-graduate degrees in Architecture and Cinematography in London. He is the author of twenty eight books. His work has been published in nine languages. His first novel The Seventh Elephant was published in Great Britain. Bar Flaubert was published in Great Britain, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Serbia and Bulgaria. American Fugue was awarded an International Literature Award from the US National Endowment for the Arts and was published in the USA (Εtruscan Press). His first book for children Alkis and the Labyrinth received the first award by the International Board on Books for Young People. His theatrical plays have been staged in numerous theatres in Athens, including the Greek National Theatre and the Greek Art Theatre Karolos Koun. He writes for the newspaper “To Vima”.

Alexis Stamatis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book Innocent Creatures, “an existential submersion in almost all fundamental human issues, mainly Love and Death”, delving into “the adventure of human existence; the nature of morality, the way people act according to what’s going on in their heads, where their most hidden secrets, their bottled-up feelings, are kept”. He also comments on how things stand as far as literary production in Greece is concerned, the role of social media in the promotion of new books and whether the essence of writing has changed in this respect, as well as on the challenges Greek literature is faced with in order to move beyond national borders and attract foreign readership.

Your latest writing venture Innocent Creatures received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book was inspired by a certain incident: a plain middle-aged woman visits the main hero, a private investigator, and tells him “Follow me”, This phrase triggered the whole book. It was the only thing I had in mind when I started writing. The title refers to all of the book’s heroes, who may get involved in shady adventures leading to devious acts, yet remaining somewhat confusingly innocent.

A noir and at the same time a deeply existential book. Which are the main themes it touches upon? Would you say that it is a book of ‘maturity’?

What I was mostly interested in while writing this book was an existential submersion into almost all fundamental human issues, mainly Love and Death. This dipole either swings as a menacing pendulum or casts its shadow over events, leading the story to an unexpected journey that leaves its indelible mark on all the people involved. It’s a novel I have been wanting to write for a long time. The people close to me who read the book told me how different it is from all the others. Yet, I believe that in its essence it touches upon the same issues as the previous: the adventure of human existence; the nature of morality, the way people act according to what’s going on in their heads, where their most hidden secrets, their bottled-up feelings, are kept.

As I write in the book: “There is a secret crypt in all people’s life that is kept seven-sealed. They know that this crypt exists inside them, they know that they can enter whenever they want but they never dare. Why? Because they are sure that all the things they were afraid since they were born will tear them apart”.

Stories, hidden marks, gaps are places where this part of ourselves that we keep secret flourishes. The novel offers the chance to shed light on all theses places and lead to journeys that it’s up to the reader to follow or not.

Does the plot unravel in the streets of Athens? Would you say that the Athenian urban landscape is ideal as a literary setting?

The plot has not so much to do with Athens; it rather unravels in a big city that could be anywhere in the world. Yet, many of my books are strongly influenced by the city I live in, which has left its indelible mark on me. The way Athens was planned, or rather not planned, or wrongly planned, has created gaps, unorthodoxies, discontinuities that are extremely interesting for a careful observer. There are so many such places, whole neighborhoods, that constitute genuine “literary settings”. They are so interesting that they could be treated as “characters” themselves.

From The Seventh Elephant in 1998 to Innocent Creatures more than twenty years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

In my first writing attempts, I used to spend so much time preparing and unraveling the plot and the characters. It’s been a long time since I neither lay out the plot nor do I spend time on preparation. The existing ideas are implemented when they are ready to be put on paper. These ideas may be triggered out of simple and everyday reasons. In my latest book, the idea came up as a result of the phrase “follow me”. The title Innocent Creatures is allegoric, ironic and at the same time literal. Based on a broadly accepted moral code, none of the book’s creatures is innocent. Yet, there is no soul void of darkness, instincts, hidden forbidden desires. What matters is whether they are brought to the surface or not. Innocent Creatures came out on bookstores less than a month before the corona virus crisis turned to the worse. Yet the book can be bought online at the following link: https://www.kastaniotis.com/book/978-960-03-6684-6.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

There is indeed a generation of young Greek writers who excel in short form. I think they are great and I am really proud that we have so many good writers. Greece has a long tradition in exceptional short form writers. Yet this in no way means that we don’t have equally great novelists. Quite the opposite. I read great Greek novels, which are additionally quite different from each other.

How do things stand as far as literary production in Greece is concerned? Has the crisis been a stimulus for artistic creation?

“The crisis constitutes a chance” is a mantra that we have been hearing for over ten years. Now with the pandemic, we will probably hear it for another ten. This enduring crisis may lead to new ways of expression, it may, hand-in-hand with technological advances, offer new terrains of creation; yet what it deprives the artist of is an independence to concentrate solely on his/her work, not being obliged to drift here and there. However, to be realistic, as things stand nowadays – this is almost self-evident. Let’s take writing, for instance: to do my work the way I want it and at the same time be secure –especially in this country – is utopian. Yet, it was in no way imposed. It is one of the few – if the only – decision of my life that I feel comfortable with. Regardlessoftheresult. After all, in art, as in life, what is important is the journey and not the result. I chose to take this risk, this insecurity, maybe because it constitutes my only hope. Andmylifecyclecorroboratestothis. By constantly reacting to perpetually changing conditions we come to create every conjuncture; and safeguard its authenticity. There are facts and there unpredictable events. Your fingerprint may always be the same, but who knows what kind of agitation runs under the skin?

In the era of online communication, what role do the social media play in the promotion of new books? Has the essence of writing been transformed in this respect?

The social media play an increasingly decisive role in the promotion of books. Whether, however, narration is adjusting itself to this new reality is something that remains to be seen in the future. What I don’t like is books that are written “in situ”, that is in a way that satisfies predefined demands. This instrumentalization – to use a fashionable word – of literature deprives art of its oxygen. An artist is transformed into a producer of wishes and desires; which, in turn, irreversibly leads to artistic death.

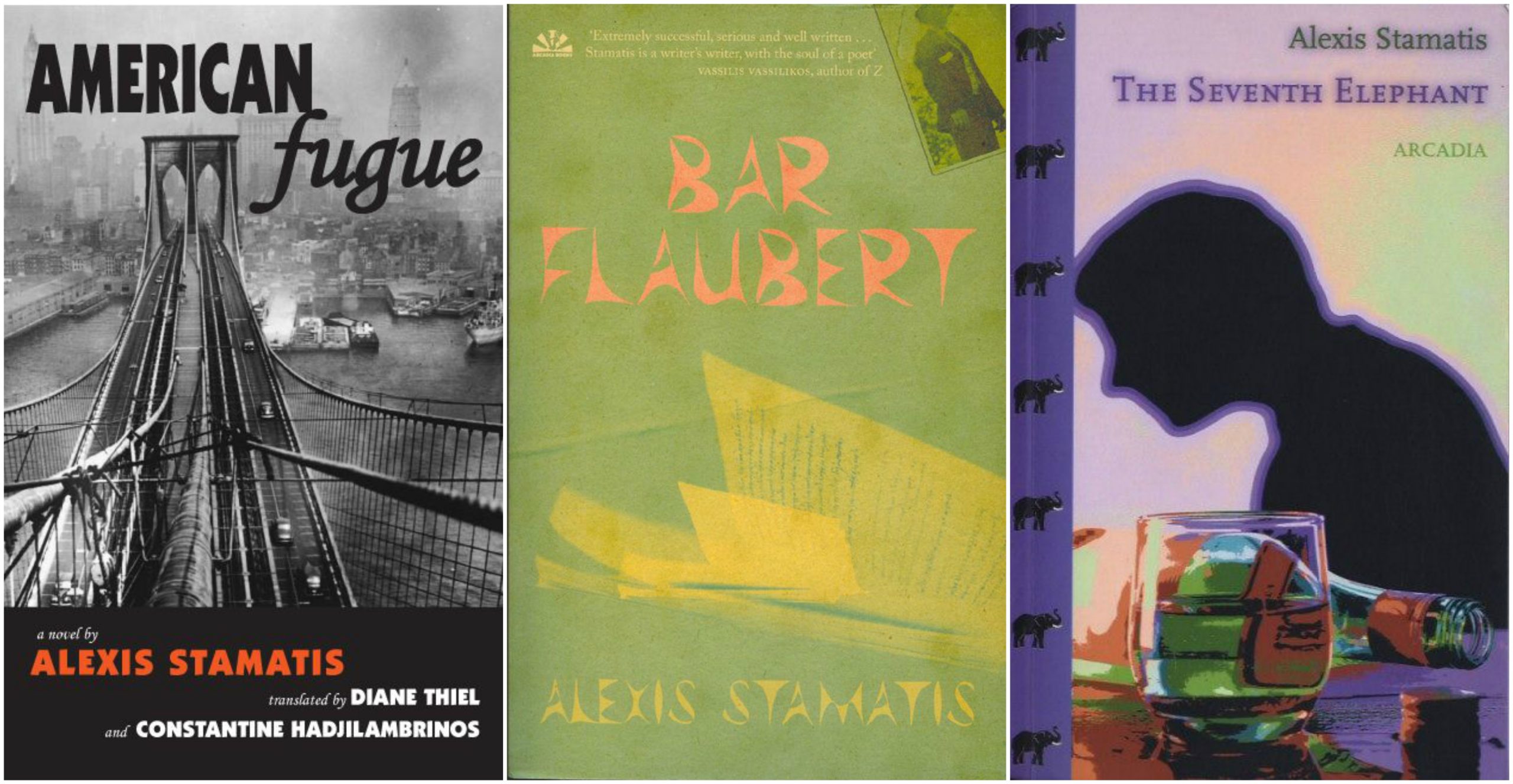

Since some of your books such as The Seventh Elephant, Bar Flaubert and American Fugue have been translated in English among others, what would you say is the ‘recipe’ for a Greek novel to attract foreign readership? How challenging is for Greek literature to move beyond national borders?

I was fortunate enough to have both my first and second book translated and published in English at a time when there was real interest in promoting the Greek book abroad. For the next fifteen years I went around the world participating in literary festivals: from Sydney to Montreal, from Shanghai to Riga, Latvia. Yet, this was mainly due to my personal contacts and the books of mine that were translated in English. Since then, things for most of us have been quite stagnant. When participating in international book fairs, Greek editors are not so much interested in selling books but rather in buying books. Modern Greek literature, delving into a panspermia of themes and issues, doesn’t seem to attract foreign readers, which would be interested in a book they could identify with “Greece”, as they envision it, that is an old-fashioned Greekness. And this is rather coercive; and yet quite conceivable since the profile Greece itself promotes has to do with its “glorious past, the sea and having fun”. In other words, ouzo, Zorbas and bouzouki, even in 2020!

Thus, a Greek writer should consider himself/herself lucky if his/her book is published abroad. On the other hand, Greek writer Christos Ikonomou has stated: “From what I have discussed with people related to the book market abroad, I get the feeling that there isn’t so much interest in national literatures anymore. What there are mainly interested in is finding good books. After all, are Greek writers really interested in such extroversion? Books are neither Greek olive oils nor Corinthian raisins; you cannot just take Greek writers and tell them we are now going to promote you abroad; not to mention that we are on a different wavelength with a significant part of foreign readers. I have heard so many different versions, “we are waiting for the next Zorba”, and my answer was that you will have to wait forever”.

Let’s wait for this terrible pandemic to end and I am hopeful that since nothing will be the same as before, the Greek book policy will be strengthened acquiring anew an international orientation. Unfortunately throughout all these years I feel I am writing as a hobby and not as a professional writer.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE