Thanassis Hatzopoulos was born in Aliveri (Evia), Greece in 1961, where he lived until 1978. He studied medicine at the University of Athens, specialising in child psychiatry, and now practises as a psychoanalyst for children and adults. He is a member of the Sociètè de Psychanalyse Freudien (SPF, Paris) and the International Winnicott Association (IWA, Sao Paolo).

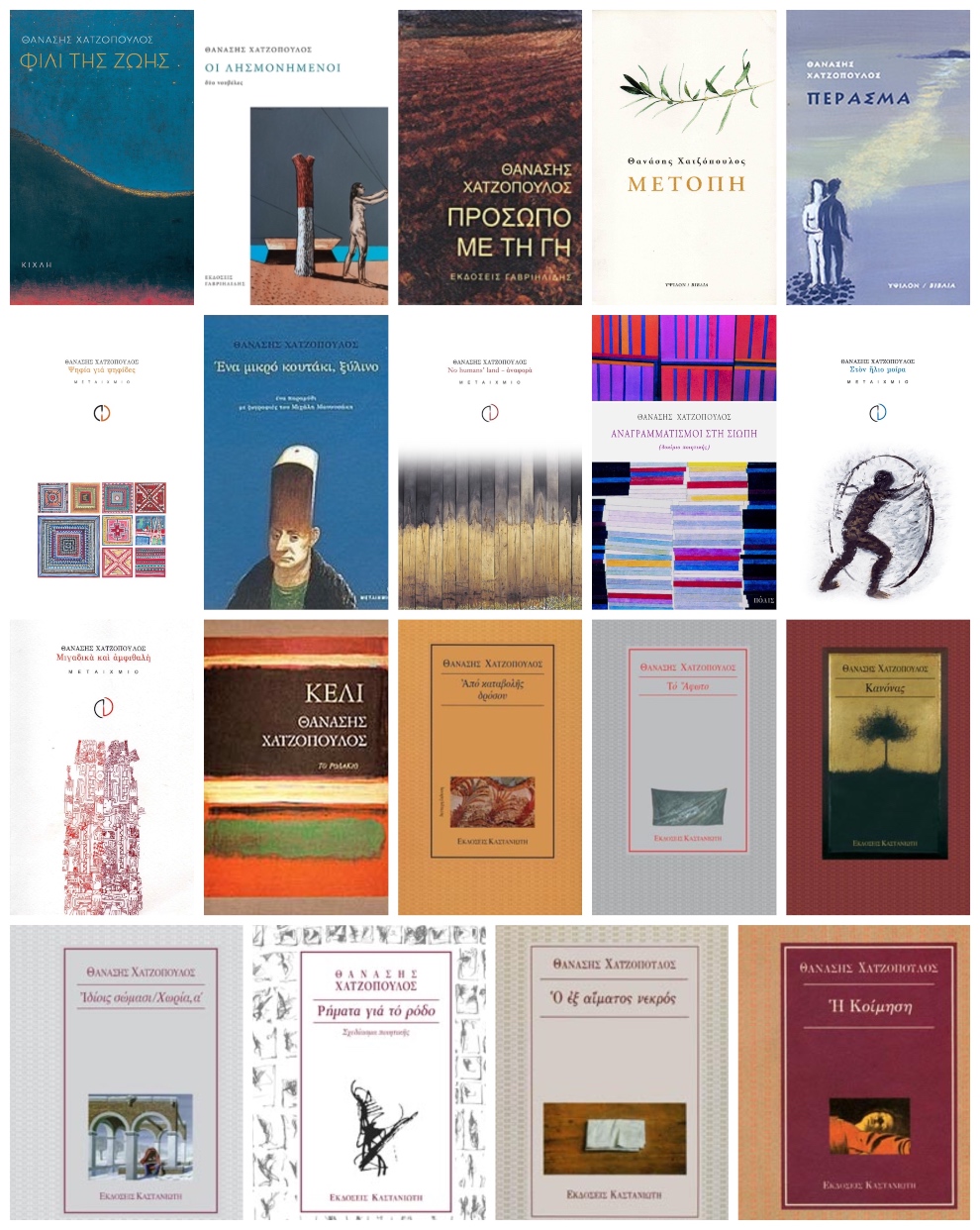

He has published the following collections of poetry: With Our Own Bodies (1986), Excerpts I (1987), The Formation (1988), The Unlight (1990), From the Dawn of Dew (1991), Dead By Kin (1994) [French translation 2000, Italian translation 2003], Fate in the Sun (1996), As If Present (1997), Canon (1998), Cell (2000) [French translation 2012], Incommensurable and German (2003) [French translation 2019], No Humans’ Land – Reference (2005), Letters for Tessera (2006), Passage (2007), Metope (2007), Face To the Earth (2012) and Kiss of Life (2016).

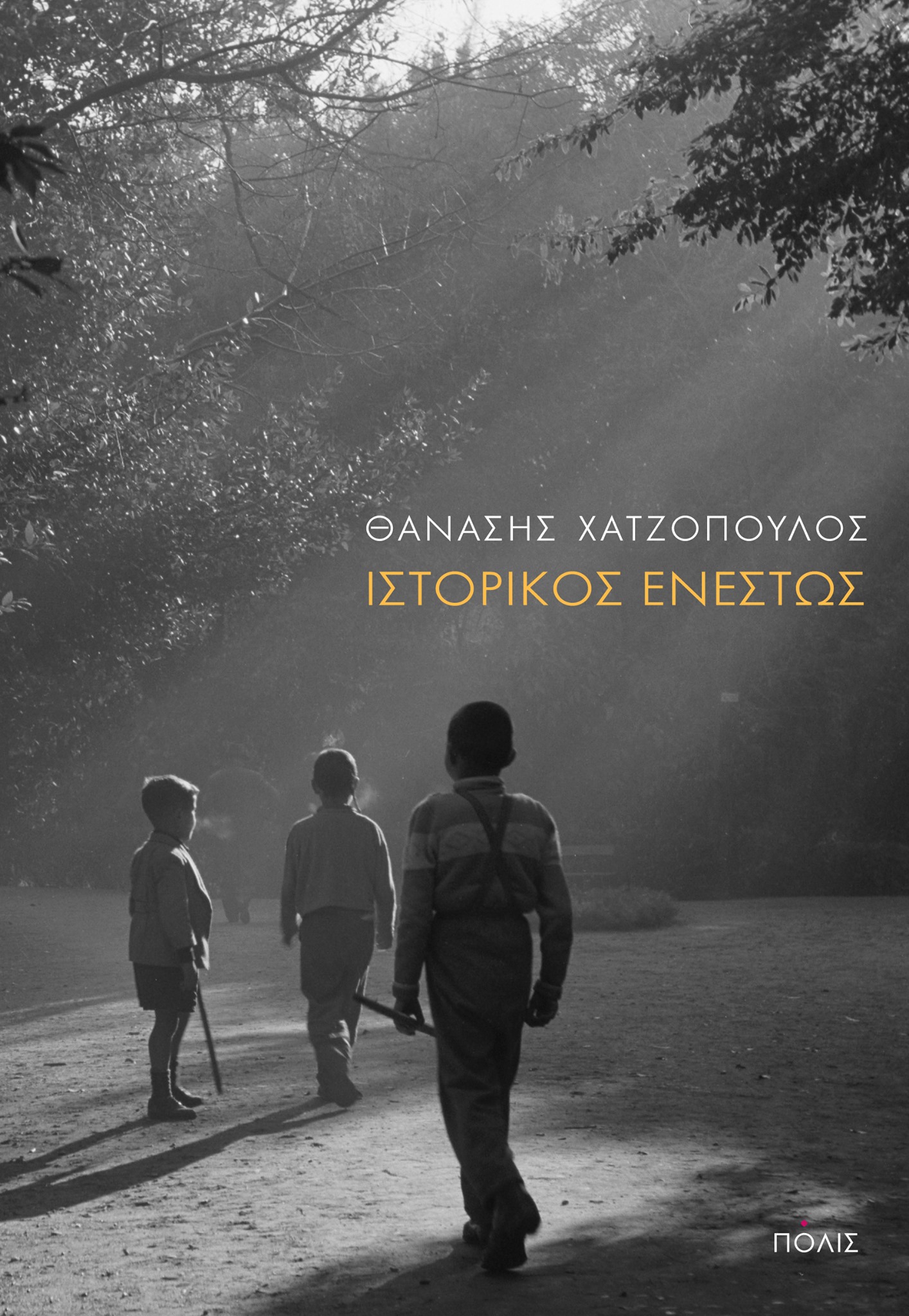

He has also published two books of poetics entitled Writings on the Rose (1997) [Spanish translation 2002] and Anagrams in Silence (2002), a tale for children, A Little Box Made of Wood (2004), two novels, The Fallen Into Oblivion (2014), a collection of short stories, Historical Present (2020), an anthology of Seferis’ Journals entitled Matters of Light (1995), and an anthology of the work of Karyotakis entitled Like a Bouquet of Roses (2001). He also contributes essays and articles to prominent literary journals and newspapers.

His poetry collection, Cell was awarded the Prix Max Jacob Ètranger 2013 in France, and his work, Writings on the Rose was awarded the National Translation Prize for 2003 in Spain. The body of his work was honoured with the Athens Academy Prize for Poetry in 2013. In 2014 he was deemed a Knight of Letters and Arts by the French Democracy. He has translated works by Jouve, Char, Claudel, Cioran, Tournier, Jaccottet, Valery, Chateaubriand, Bonnefoy, Dupin, Du Bouchet and Viriginia Woolf. He has also translated works by the British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott, Hanna Segal and Otto Rank.

Thanassis Hatzopoulos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest writing venture Historical Present, which comprises “stories of ordinary people”, who “appear not to have contributed to the course of great History”, while also “unable to give meaning to their own life”. Asked about the main themes his poetry touches upon, he mentions, among others, “the human being and its existence, their passions and misfortunes…the body and its mournings, myths born out of disasters, the frugality and magnitude of nature”, commenting that what’s important for him is the “interrelation of these themes and the way in which they leave their imprint on language”. As to whether poetry and psychoanalysis are communicating vessels, he notes that “their meeting point is speech”, which, “in its flowing process, creates cracks, even fissures, in places where there was previously only solid rock and thus helps unearth new conditions”.

Your latest writing venture Historical Present [Ιστορικός Ενεστώς] was critically acclaimed upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The book comprises stories of ordinary people, the way they lived throughout their course of life, whether long or short, eventful at times, almost dull at others. People who appear not to have contributed to the course of great History. People who left almost no imprint at all. Yet, even those who lived an almost fugitive life or those whose presence was far from remarkable, those whose imprint was barely distinguishable so that it was erased the moment it was carved, have contributed to the course of History. Even if you classify them in the inert part of life, they function as a form of resistance. In other words, they cause imperceptible changes or delay changes that are to occur. Those invisible people who express no opinion on what happens in their life, and life in general. Most of them possibly fall within the category of people who don’t vote in the elections. People whose lives don’t flourish but are rather drowned or latent. Those for whom life, starting from birth, never actually counts. A great number of people who define through their own indeterminacy the future of us all. I wanted to shed light on all those lives which don’t always succeed in leaving their imprint or to give meaning to the word life; in essence people who are unable to give meaning to their own life. They are born and die as if life were solely a natural phenomenon. These stories aim to provide an imprint, meaning, depth, weight and soul to this natural phenomenon. To let us know that there were people who lived and will live these lives. Themselves being forms of life.

“We cannot conceive ‘normality’ without taking into account its variations/exceptions“. Could you elaborate on the way the notion of normality is employed in the book? What purpose does the alternation between katharevusa and demotic language serve?

This phrase comes from my interview to Michaela Hartoulari (published on 11 March 2020 in Efymerida ton Syntakton), during which reference was made to the dipole normality/non-normality. Yet normality extends over a wide spectrum, with a great number of exceptions and variations. That isn’t something I had in mind when I was writing the book. For me all the characters are normal and, if you like, so normal that they are uninflicted by this normality, which to others may appear as not normal and from which, for example, the writer who gave them voice would also suffer. After all, the materials that make up this so-called normality and what is considered not normal -usually connected to averages and social conditions- are exactly the same. Let’s not forget the way homosexuality was treated in the West a few decades ago, but also today in certain parts of the planet, and how this stance has changed in most of the western countries today. Or what the position of women was a century ago.

Even words themselves suffer in accordance with the era, regarded, from a spelling point of view, as normal at certain times and abnormal at others, subjected to an obligatory change of form. On the other hand, creation and destruction are also made up of exactly the same materials. What differs is the aim and the course. Psychoanalysis has, if you like, blurred the distinction between what is normal and what isn’t. Showing that there is a continuum. On the one end of the dipole “normal/not normal” one could find disease yet, on the opposite end, over-normality could be proven equally ill. Fortunately man is not a machine, and can neither be fully controlled by any system nor completely subjected to it. He possesses freedom safeguards which lead to diversity and creative exception. The same applies to language. Even through a language that is conventional or bureaucratic, literature can trigger emotions.

The alternation observed in the language of my texts was imposed by the content itself of each story so that the reader is at the edge of emotion, the dramatic element in turn appearing and disappearing so as to simultaneously bring about both identification and distancing. This is the balance I tried to achieve through the use of mixed linguistic elements, at times closer to katharevusa, at others closer to the demotic language, drawing upon a language which, in its historic depth, allows for much flexibility and offers a great richness, enabling us to present the most subtle and lost senses and emotions. The Greek language possesses an ontological ability for rebirth, much greater perhaps than other languages, due to its historical past.

After 14 poetry collections so far, which would you say that are the main themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

In retrospect I have come to realize after these 14 books, and some others still unpublished, over a period of almost 35 years, that there are recurrent themes, as well as others that have come to pass. The human being and its existence, their passions and misfortunes, their stories, their falls and rebirths, their moments of ecstasy, life that overflows and flourishes, the body and its mournings, gratitude towards life itself, myths born out of disasters, the frugality and magnitude of nature, could be some of these themes. Though definitely rather commonplace, what’s important for me is the interrelation of these themes and the way in which they leave their imprint on language. What matters is the poetic excavation where language has reached its limits and the way these limits are poetically put to the test. And, alongside this, the extent to which the core is also refurbished and from which something renewed and extremely deep may emerge in the simplest way. Experience constitutes a barricade, a bridgehead which excavates and is excavated linguistically, that is poetically, taking the human condition even further, said “further’ constituting both an extension and a deepening. This could, as far as I am concerned, be a point of reference.

Would you say that poetry and psychoanalysis are communicating vessels? What is their meeting point?

I like your metaphor of communicating vessels given that speech indeed flows like water. Water, as an element, has a penetrating strength which no other natural element possesses. It doesn’t merely search for imperceptible cracks through which to pass, but also has the power, through time, to create them. I see a similar strength in speech, which unfolds and at times is presented in various forms, from poetry and narration to myths and fairytales. This mainly occurs in everyday life, though at a microscopic level, in a way that becomes evident only through its consequences and results, which most of the time keep their sources well hidden. In this respect, speech, in its flowing process, both in poetry and in psychoanalysis, creates cracks, even fissures, in places where there was previously only solid rock and thus helps to unearth new conditions. Nothing remains impermeable. Simply this gestation is long, with time as a necessary prerequisite. Without it, speech can no longer flow. Similarly, the time for a poem to be written, or for a change in psychoanalysis to be achieved, is so long that one cannot discern either the how or the when.

A symptom may require two or three generations in order to appear. And I could claim the same for a poem. The subject of the generation that will heal the symptom could be similar to the one that will write the poem. There are half-hidden stories both in symptoms and in poems. Which are equally half-apparent. Speech is similar to an iceberg. There is the visible part, and the hidden one that involves even the links and associations of one word accompanied by a respective constellation of other words. In short, speech and language constitute both for poetry and for psychoanalysis the structure and operation of a system on which our psychosomatic life and history is based. Both the structure, that is the anatomy, and the operation, the physiology, to use medical terms. Psychoanalysis de-constructs and re-constructs through the speech addressed to the analyst, while poetry re-composes and re-creates through its verse addressed to the reader. Their meeting point is speech. But this is the core of life, as long as there is a material background. Because speech, too, is in need of embodiment.

What is the relation of literature to the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to debunk stereotypes about your ancestry and past and help ‘re-brand’ our national image?

Literature has always been a child of its time, its era. This is one of its aspects, where a small part of an era is reflected. Texts are born on the sharp edge of their times interweaved with a future either distant or immediate. Like children who are born to live under different conditions to those of their parents. Of course the distance they are meant to cover depends on their potential to map personal truths within historical, philosophical, anthropological contexts. On their strength not so much to visualize a future but to carve out anew the human condition in its past. In this respect, indeed literature aims to liquefy stereotypes. To provide plasticity to what has become rigid and restricts movement instead of allowing its evolution and unfolding. To offer new form to what has been shrunk; since every stereotype constitutes a kind of shrinkage.

The national image may just be an elusive aspect of identity, of every national identity. Necessary, yet up to a point. The national identity, which is far from static, cannot be limited to the image. When it becomes static, it is restraining. Not that there aren’t stable elements in national identities. Just this stability is dynamic. They are constantly re-constructed and re-created. This being the purpose and duty of every generation. This means that each generation searches for and uses the materials of the previous ones to form its own identity. The Greek identity certainly wasn’t the same at the beginning of the new century to what it had been in the 1980s, neither was the former the same as the present one. The lies every generation adopts for itself should not merely be shaken off by the future ones, but reconstructed as well. Behind every such identity, either counterfeit or plausible, lies a specific opinion -or the lack of an opinion- as to living, life and the place we have been bestowed with, and must live in. And every generation is judged on this, the work it fulfills within its specific time and place.

Could a multi-faceted socio-economic phenomenon trigger a poetic ‘cosmogony’ and possibly a ‘new generation’ in poetry? If so, based upon which poetic and aesthetic criteria?

Cosmogonies, poetic or otherwise, don’t come about every few years. Neither are we taken aback when they do. The turn of Greek poetry attributed to Seferis, an outstanding poet, gradually unfolded in the years preceding 1930 with the pivotal contribution mainly of Cavafy, Sikelianos and Karyotakis, three considerably different poets. Papatsonis also falls within this category. On the other hand, Palamas, from whom it was basically necessary for distance to be taken, is also a part of this turn, if one considers the massive change in times. And behind him there is Solomos, an inalienable point of recovery and distancing as well. Without the breakthroughs they all achieved, there would be no Seferis. And this regardless of his own points of reference. This means that social and economic changes, alongside them poetical, are, prior to their occurrence, gestated and in preparation for years and years, either in a destructive or creative way, without excluding the element of the coincidental. After all, every creation presupposes some destruction, without which it couldn’t exist.

The poetic and aesthetic criteria are also configured on the basis of the way in which they are received at any given era. For instance, photography and the cinema drastically changed these criteria in poetry, in the same way painting did. Nowadays, the invasion of technology coupled with the transgression of the boundary between in and out, private and the public, interior and exterior, as well as the change in the subjective dimensions of time and place with speed, have caused the world to diminish or grow respectively, in a digital manner I mean, bringing closer that which stands at a distance. These constitute cosmogenic changes in the perception of the ‘natural’ and the human. Their transformation into poetry and impact on the aesthetic sphere remain, in short, unknown. Only in retrospect, as usual, will we be able to discern it. After all what is at stake is what will remain steady in the face of these sweeping changes or how the human psyche and societies will react or be altered. Even the notion of death may change, as man seems to become more and more comfortable in the illusion of almightiness thanks to technological advances, at the same time that wear and tear continues its own work. Of course, there are circumstances, such as the current pandemic or wars and terrorism, both in the past and nowadays, which leave no place for complacency given that what characterizes humans in essence is their vulnerability. This vulnerability along with the fantasy of almightiness constitutes the core of literature.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE