Dr John Kittmer, British Ambassador to Greece from 2013 to 2016 and passionate Hellenist left the British Diplomatic Service in 2017 to complete his PhD on the Greek poet Yannis Ritsos at King’s College London. He learned ancient Greek at school, and studied Classics at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford, while he obtained an MA in Modern Greek Studies in 2007 at King’s College London. After completing his PhD in 2019 Dr Kittmer is now working on several publications based on his doctoral researches. He is also Chair of The Anglo-Hellenic League, a charity dedicated to the promotion of friendship and understanding between Britain and Greece, and a Member of the Board of Okeanis Eco Tankers.

Last February Dr Kittmer, who is a fluent speaker of Greek, was in Athens to give a lecture titled ‘Anglo-Hellenism: Adventures in Cultural Exchange’ -organised in collaboration with the Centre for Hellenic Studies, King’s College London in honour of Niki Marangou- where he spoke in Greek about the powerful cultural and educational bonds between Britons and Greeks. [A full video-recording of this lecture can be found here].

Dr Kittmer recently spoke to Greek News Agenda* about his admiration for the ancient and Modern Greek literature, his impressions of Greece as a British Ambassador, the role of social media in cultural diplomacy and the future of anglo-hellenic cultural exchanges. Dr Kittmer has a personal Twitter account (@JohnKittmer) and a blog titled “ανταποκρίσεις-correspondences” writing in English or Greek about the things that interest him, including his academic studies, his charity work and the maritime sector.

It is not a secret that you are a lifelong admirer of the Greek classics with a deep knowledge of the ancient, but also Modern Greek literature. What exactly do you admire the most in Greek culture or in Greece in general?

My admiration for Greece and the Greeks has several dimensions but is founded on the Greek language. I started to learn ancient Greek nearly forty years ago and modern Greek not long after that. Longevity, flexibility, complexity, nuance, elegance: these are good reasons to keep returning to this enchanting language. In all its forms it is something to be savoured, enjoyed and, occasionally, wrestled with. It always pays back. It is the well-spring of our civilisation, the source and medium of a profoundly rich literary culture. Thinkers in Greek posed all the great questions; probed, shaped, stored and transmitted knowledge; gave voice to the ineffable; articulated philosophy, theology, poetry, history, rhetoric, mathematics, drama, liturgy, song. And it has maintained its prestige across time, producing two Nobel Laureates in the twentieth century. The language of Homer, Plato, Euclid, the Bible, the Akathist Hymn, Cavafy, Seferis… Once you start to learn it and fall in love with it, there is no going back: you can’t put it down.

Yiannis Moralis “Classical Athens”, 1966. Source: nikias.gr

You were the ambassador of Britain in Greece for the period 2013-2016 right in the middle of the Greek financial crisis, but you are still connected with the country. How do you see the future of Greece after the country’s gradual economic recovery? Do you feel that the crisis has affected the spirit of Greeks?

I was British Ambassador at a traumatic time for Greece, when the arguments over the first and second memoranda pushed Greek society and politics close to a breaking point. Life was economically difficult for very many Greeks, as you know better than I. I was disturbed by the pervasiveness of national self-criticism, by the palpable sense of national embarrassment, anger and shock; it seemed dangerous to me – as if Greeks had lost all confidence in the ground on which they stood. I tried to do what I could to support, to express my admiration for the Greek people, and to reflect back the good things I saw in Greece, among its entrepreneurs, its professionals, its artists, its students and many others. Knowing what I do about Greek history, I believed strongly in Greek resilience: in the solidity of the Greek family and of Greek society. I saw good reasons for long-term optimism: in your respect for education, in your spirit of enterprise, in your profoundly democratic and generous instincts, and in your mutual solidarity.

I am therefore delighted, but not surprised, to see Greece emerging from its economic difficulties and its existential anxieties. Of course, we are all being tested now by Covid-19. The Greek response to this extreme challenge is impressive. The Government and people appear to trust each other. No doubt all our economies are encountering a short-term shock, but your spirit – your kefi – is inextinguishable. I see no reason why Greece shouldn’t bounce back, as you continue to develop your great strength (the tourism sector) and take steps to diversify your economy.

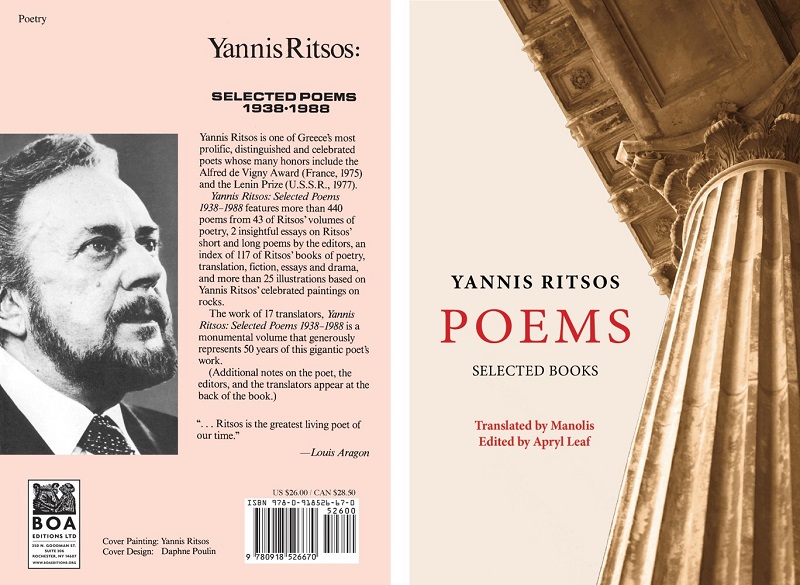

You have recently been awarded a PhD in Modern Greek literature at King’s College London for your thesis on the poet Yannis Ritsos. Why did you choose this Greek poet?

My PhD thesis is a very small token of my very high esteem for a great poet and a great man. I started to get interested in Yannis Ritsos in the late 1990s. The more I read his poetry and the more I learned about him, the more fascinated I became. On the one hand, his career as the poet laureate of the Greek Left is remarkable. Having come under Communist influence in his late teens, Ritsos lived the tumultuous history of the Left. His life and work were marked by suffering, illness, courage and prolific creativity, and are a good way to understand important aspects of the torments of the Greek twentieth century.

But on the other hand, his poetry is something apart; it speaks for itself. As an engagé poet Ritsos is, I think, a paradoxical figure: he was Communist but had metaphysical instincts. He paid some attention to Socialist Realism in the 1930s and 1940s, but his influences were eclectic – Symbolism, Russian Futurism, Surrealism – and he maintained a defiantly Modernist aesthetic, despite the Party’s disapproval. His imagination was deeply rooted in traditional images of Greekness, but his mind explored world literature (he was a prolific and underappreciated translator). Complexity, paradox and a Protean character lie at the heart of his poetic greatness. Ιn my view he is a very great poet, who lived the vocation of a poet as few others do. Can you understand Greece without knowing Romiosyne, The Lady of the Vineyards, Petrified Time, The Moonlight Sonata, Orestes, Testimonies, Repetitions, Gestures, Corridor and Stairs?

You are an active social media user and you were also making use of this tool of communication, while you were ambassador in Greece. What do you think about the role of digital technology in cultural diplomacy or in public diplomacy in general?

I would say that I’m a selective user of social media! Over the past twenty years, social media – for better or for worse – have become part of our lives. Personally, I am hostile to the business model of the main platforms and their commercial harvesting of personal data. I have a personal Twitter account and a blog, and I am attached to them, but that’s it. I use them as a source of news and to communicate about the things that interest me in Greece and the UK: literature, travel, culture, economy, politics, environment, religion, shipping.

Professionally, my Embassy used Twitter, Facebook, Flickr and Instagram, and we blogged in English and Greek. In an age when people get their news from many sources, diplomats need to engage widely and to have modern communication skills. Elements of diplomacy require secrecy, confidentiality or unobserved action behind the scenes. But Governments also want to explain themselves to non-governmental audiences. I also wanted to demystify elements of embassy and consular work. We were, I think, one of the most active embassies and I’m proud of what we did. I tried to be careful: diplomats talking publicly overseas are walking on a high wire. You are paid and instructed to transmit your own Government’s policies and positions, but you have to be sensitive to the audience. I didn’t want to become a by-line for propaganda. Personal authenticity and integrity matter. I was also aware of the risk of provoking hostility: on the social media, it is easy to stir up cynicism, insult and abuse. For me, the best moments were the positive interactions that helped us understand Greece better. Some of my Twitter followers from that period have since become good friends.

You are chairing the Council of the Anglo-Hellenic League. How do you see Anglo-Hellenic relations over the years, especially in the post-Brexit era?

The Anglo-Hellenic League was founded in 1913. We are a charity promoting friendship between Britons and Greeks. Since our foundation, Britain and Greece have shared together triumphs and moments of darkness: not least moments when we were at odds with each other. I had the privilege recently of giving, in Athens, the second annual lecture in honour of Niki Marangou and spoke at length in Greek about British-Hellenic relations, particularly (but not only) our cultural relations.

Political and commercial relations between our countries are good and, while Brexit poses some challenges, I don’t see that position changing. Since the 1950s, however, the most important relations between Greece and Britain have not been political or commercial but cultural, educational and personal: Greek students studying in the UK higher-education system, British students of Hellenism (ancient, Byzantine and modern) studying at home and in Greece and Cyprus; Greek writers, artists and musicians who have been inspired by Britain; Britons whose creativity has flourished in Greece and Cyprus; our travellers and tourists who every year fall in love with each others’ country.

This cultural and personal dialogue is a huge success. Much of it rests on individuals, their talents and their visions. But much too rests on institutions, foundations, sponsors, publishers, galleries, conservatoires, universities. None of us yet knows what impact Brexit will have on the quality and intensity of these exchanges. Much is to be decided in the months ahead. I hope our politicians will make the right decisions: those which foster friendship, mobility, co-operation and exchange between Brits and other Europeans, including of course Greeks and Cypriots.

Next year, Greece will celebrate its bicentennial. The League will be playing its part in London and we are now working out our ambitions for the celebration. This is a great opportunity for Anglo-Greek cultural exchanges. I am thinking not just about 2021. For British philhellenes 2024 (death of Byron), 2027 (Navarino), 2030 (Treaty of London) are all important parts of the bicentennial. If we plan properly, we have a decade to promote Anglo-Hellenic cultural exchange, to raise funds, build legacies, create endowments and build a strong platform for the future. It is an exciting prospect. And in the process, I hope we will inspire more young Britons to engage with Hellenism and, as I did forty years ago, to fall in love with Greece and the Greek people.

* Interview by Ioulia Elmatzoglou

Read more via GNA: UK Ambassador to Greece John Kittmer’s farewell |Between peasants & intellectuals: Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Greek friends | Lecture: Lord Byron and the bailouts | Rethinking Greece: Roderick Beaton on the study of Greece and modern Greek achievements | The works of the “Greece 2021” Committee are launched

TAGS: GREEK LANGUAGE | HERITAGE | HISTORY | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | LITERATURE & BOOKS