By Alexandra Kouroutaki

Alexandra Kouroutaki is a member of the Laboratory teaching staff (EDIP) at the School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete. She holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, a Postgraduate Diploma in French Literature from the School of Humanities of the Hellenic Open University, and is an honors graduate of the Department of French Language and Literature of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Introduction

Introduction

The Crucifixion of Jesus as part of the process of salvation and victory over death is of central importance in Orthodoxy. The iconography of the Crucifixion and the Holy Passion, as depicted in icons and frescoes of historical churches in the city and the prefecture of Chania, provides an interesting journey in local iconography.

The aim of this study is to examine representative works of religious art from the thematic cycle of the Holy Passion which illustrate the evolutionary course of local religious painting. The iconography and technique of the works are characterized at times by elements surviving from the Byzantine tradition or of Western art influences. Historical and social factors are also highlighted, as well as the iconographic types that marked the aesthetic orientations of visual hagiographers. The critical analysis is based on the specific terminology of Art History.

The study consists of three parts: The first examines icons of the 17th century depicting the Crucifixion and the Epitaph, painted by the prominent post-Byzantine iconographers of Chania, Konstantinos Paleokapas and Theodoros Poulakis, considered as successors to the tradition of the Cretan School; the second part refers to important local iconographer-painters who followed western standards and lived at the turn and the early decades of the 20th century. In particular, the study explores the successful integration of Western elements in their work; the third part examines the return of iconography post-1950 to the Byzantine tradition, with frescoes of the Crucifixion painted by native icon painters, students of Kontoglou and successors to the Cretan school tradition.

Depictions of the Holy Passion in post-Byzantine icon painting of the 17th century

The introduction of western art standards in Orthodox religious painting in Crete took place progressively under the influence of the Venetians since the second half of the 15th century. The integration of western elements in orthodox visual hagiography continued into the 16th century with the leading icon painters of the Cretan School who developed a particular style of icon painting, combining Byzantine tradition with elements of realism and naturalness[1] that were characteristic of Western painting.

The journey depicting representations of the Crucifixion begins with two 17th-century portable icons, painted by Konstantinos Paleokapas and Theodoros Poulakis. In their multi-faceted compositions, various episodes of the Crucifixion are dramatically and intensely narrated. The icon of The Crucifixion by Constantine Paleokapas (Museum of the Monastery of Our Lady of Gonia or Monastery of Panagia Hodegetria, Kolymbari, about 26km from Chania), presents an interesting mix of Byzantine and Western motifs.

The figure of the Crucified Christ commands the centre of this composition, with the two thieves to his left and right. Christ is depicted leaning to the right, wearing only a white loincloth around, whilst the Archangels Gabriel and Michael encircle the top of the cross. Following Byzantine standards, the painter depicts the rocky peak of Golgotha where the Lord’s Cross stands and beneath it a cave where the skull of Adam can be seen[2]. To the right of the Cross stands the Virgin Mary gazing at her Son and expressing her pain stoically, while to the left of the Cross we see John. There are also Roman soldiers, a crowd of Jews, and the walls of Jerusalem are depicted in the background.

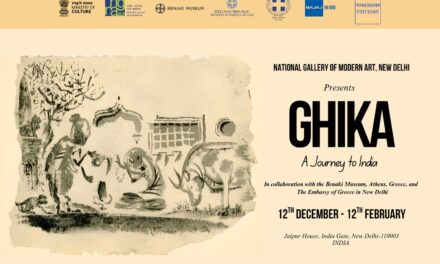

Left: K. Paleokapas, icon of The Crucifixion, 1635-1640, Museum of the Holy Monastery of Odigitria, Gonia Kolymbariou, Chania http://www.libraryoac.gr/el/. Centre and Right: Jan Sadeler, The Crucifixion, 1582, Copperplate engravings[3](Wikimedia commons)

Left: K. Paleokapas, icon of The Crucifixion, 1635-1640, Museum of the Holy Monastery of Odigitria, Gonia Kolymbariou, Chania http://www.libraryoac.gr/el/. Centre and Right: Jan Sadeler, The Crucifixion, 1582, Copperplate engravings[3](Wikimedia commons)

In his composition, Paleokapas deals creatively with two subjects that derive from 16th century Flemish copperplate engravings: the Roman centurion Longinus piercing the side of the crucified Lord with his lance and the tearing of His clothing. These issues are also addressed by Jan Sadeler in his copper engravings of the Crucifixion[4]. Regarding the technique, Paleokapas maintains the Byzantine portable icon tradition depicting the scene against a golden background.

Noteworthy also is the case of the progressive post-Byzantine iconographer Theodoros Poulakis (1622-1692) from Chania[5]. In the iconography and style of his religious compositions he follows the Byzantine and Italian traditions, but there are also influences from Baroque art[6] and the Naturalism of Flemish Painters.

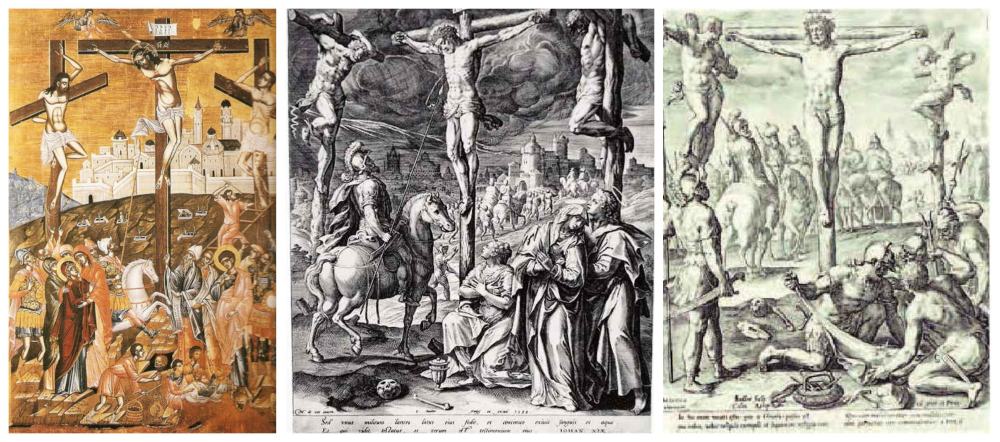

Left: Th. Poulakis, The Holy Trinity, The Descent into Hades, Christ in Paradise and the Epitaph, second half of 17th century. Byzantine & Christian Museum of Athens https://www.byzantinemuseum.gr. Right: Th. Poulakis, The Crucifixion, Holy Monastery of Panagia Chrysopolitissa, Larnaca, Cyprus, second half of 17th c. (Source)

Left: Th. Poulakis, The Holy Trinity, The Descent into Hades, Christ in Paradise and the Epitaph, second half of 17th century. Byzantine & Christian Museum of Athens https://www.byzantinemuseum.gr. Right: Th. Poulakis, The Crucifixion, Holy Monastery of Panagia Chrysopolitissa, Larnaca, Cyprus, second half of 17th c. (Source)

In his portable icon The Holy Trinity, the Descent into Hades, Christ in Paradise and the Epitaph, Poulakis creates a rhythmic composition. The Epitaph depicts the Virgin Mary with contained sorrow to the right of Christ and two female figures accompanying her. Marie Magdalene, the mourning Myrrhbearer and apostle, is depicted in a bright red garment lamenting inconsolably. On the other side of the Cross, young John is depicted along with two other male figures.

The icon painter presents the theological and dogmatic concept of the event. As is often the case in Orthodox iconography, it does not narrate the facts independently, but presents them in sequence. The Crucifixion is part of the process of Salvation. The Cross that dominates the composition is placed and rooted as a tree of life in the dark cave of Hades (see Descent into Hades) while Christ is depicted standing on the crumbling gates of the cave of Hades to abolish him forever.

Both in the icons of the Epitaph and of the Crucifixion, Poulakis’ influences from Western art are evident, and the figures depicted acquire substance through their expressive positions and movements. In this context, it is worth noting the dramatic tension of the whole scene, the psychological penetration, the first attempts of restoring perspective of space and the use of bright and glistening colours. However, Poulakis uses egg tempera on wood, the traditional technique of Byzantine art and is not interested in oil painting. He contributed decisively to the integration of European aesthetics in Orthodox religious painting, a tendency followed by the Ionian School of iconography.

The Holy Passion in Chania’s western-style icon painting towards the 20th century

After the occupation of Crete by the Turks in 1669, the iconographic styles of the Cretan School of icon painting survived with Cretan iconographers who did not leave the island and continued their creative work under difficult conditions. With the proclamation of Crete as an independent Cretan state in 1898, a period of development began for the Cretan people who tried to heal their wounds after two centuries of subjugation. Following the union with Greece (1913) and during the Interwar period, there was significant creative activity in Chania, where local iconography preserved the western style that was established.

An important Western-style icon painter who was active in Chania was the Reverend John Kalliterakis (before 1878 – after 1924)[7], educated[8] at the School of Arts[9]. The western influences on his work are evident in the portable icon The Deposition (1893) which adorns the Metropolitan Church of the Presentation of the Theotokos (Mother of God) in Chania.

For this composition, Kalliterakis used as a model the Baroque style of the French painter Jean-Baptiste Jouvenet in his oil painting La Déposition de Croix[10]. The paintings depict the scene of the deposition of Jesus’ lifeless body from the Cross. In the multifaceted scenes of both compositions, with groups of men and women to the right and left of the Cross, the dominant elements are sadness and lamentation, and on the Cross, the icon painter depicts the vigorous efforts of the disciples to hold the limp head and body of Christ.

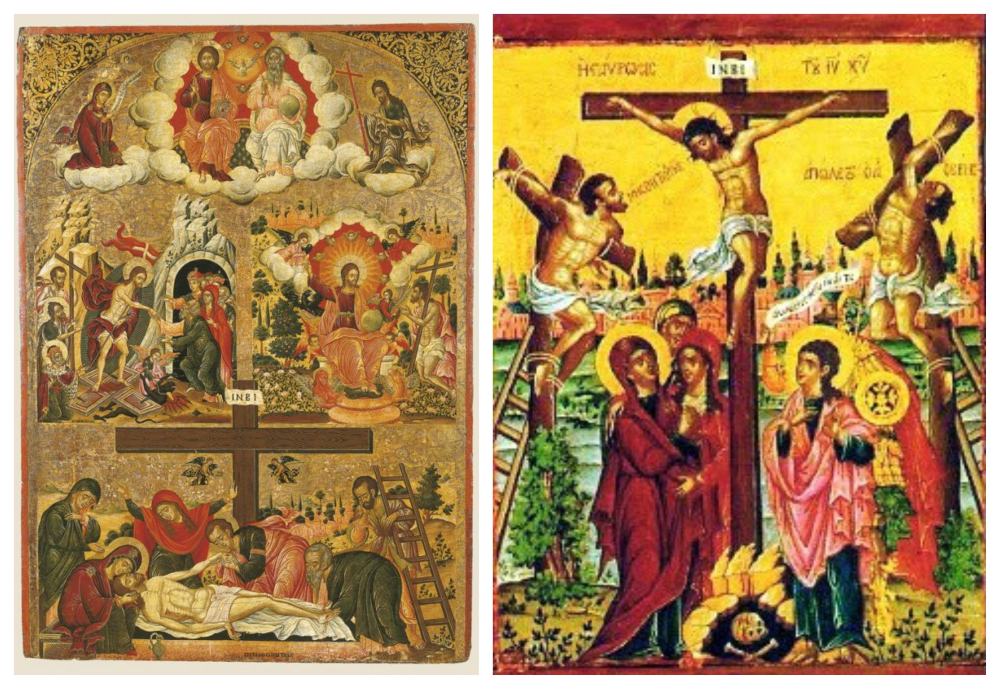

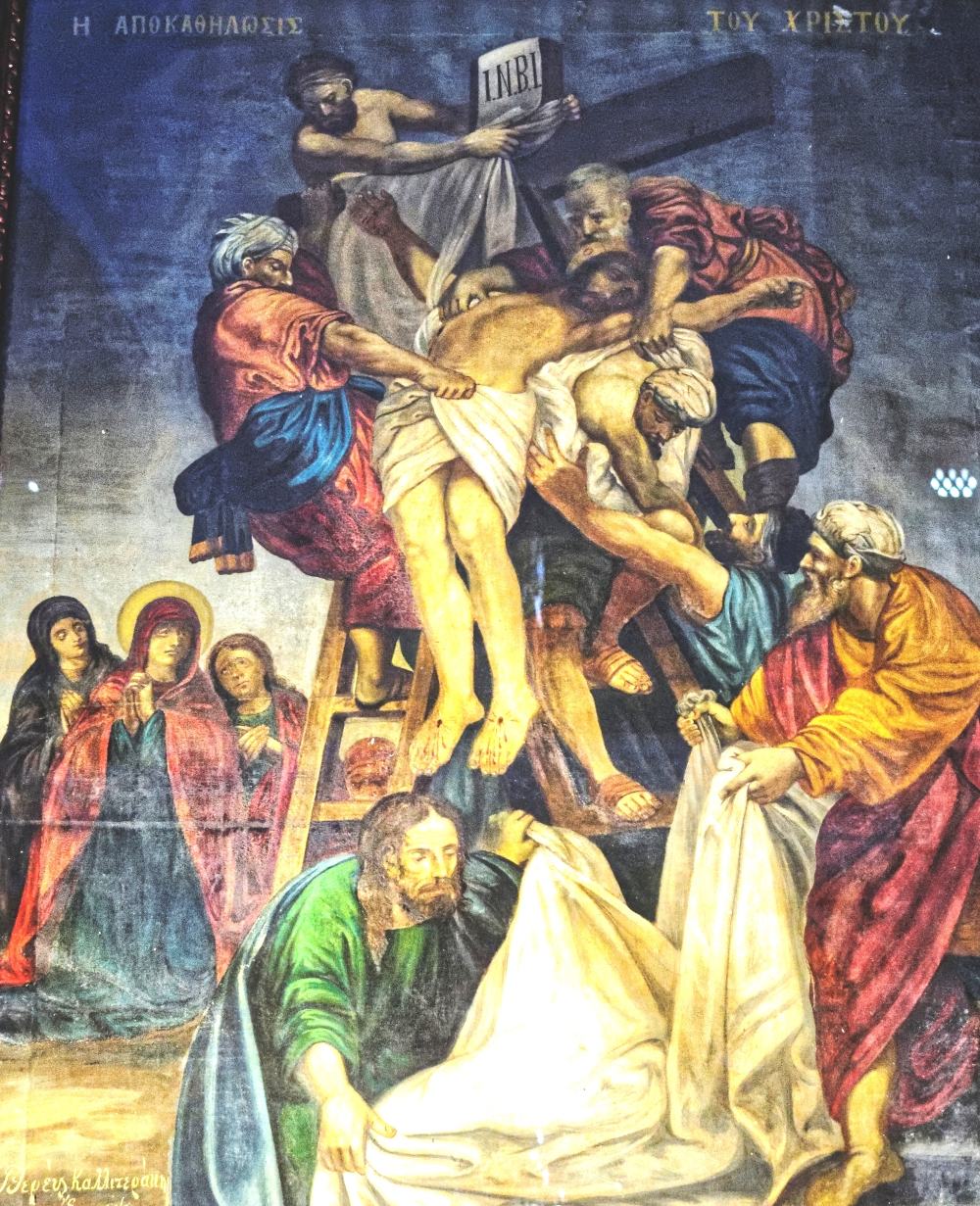

Reverend I. Kalliterakis, The Deposition, 1893, Church of the Presentation of the Theotokos (Mother of God), city of Chania. Photo by M. Kimionis

Reverend I. Kalliterakis, The Deposition, 1893, Church of the Presentation of the Theotokos (Mother of God), city of Chania. Photo by M. Kimionis

The culminant point of the composition of Kalliterakis is the figure of the Lord that has just been deposed and is represented with the full weight of a lifeless body. The Virgin Mary and the Myrrhbearers are presented on the left side of the composition, as is often the case in post-Byzantine iconography[11]. The dramatic element and the intensity of the movements of the figures are impressive. To achieve this, the iconographer presents a laboriously detailed composition emphasizing the interchange of light and shadow and the use of vibrant and harmoniously combined colors.

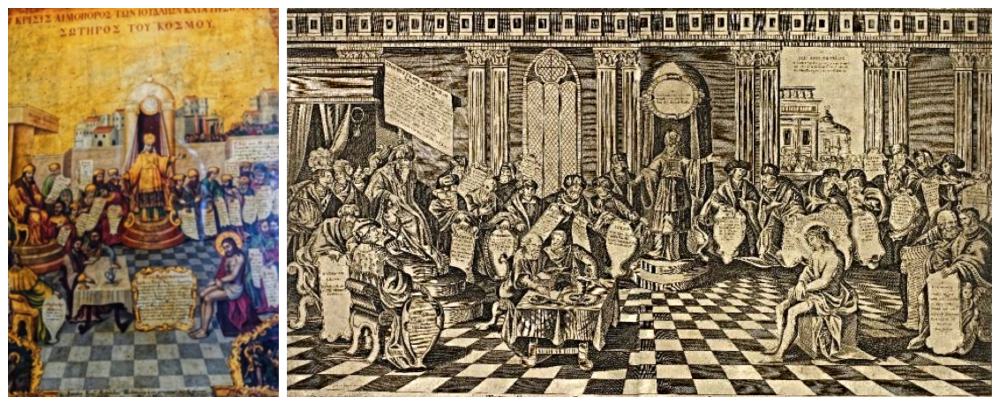

Εmmanuel Papadakis was an important western-style scholarly icon painter in the early 20th century. The icon Bloody trialagainst Jesus Christ the Saviour of the World (1903) at the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Presentation of the Theotokos in Chania is an impressive example of his art, combining popular style elements with Western influences. The standard for this composition by Εmmanuel Papadakis was an 18th century copperplate engraving of the trial of Jesus[12]. The composition depicts Pontius Pilate and Caiaphas on a throne.

Christ, on the right side of the composition is on the stand. The pictorial space is depicted in perspective and reminds of a stage setting with the help of the architectural elements of the composition. The Jewish people are also a part of the composition, attending the trial from the gallery as the judges have written their verdicts for the accused on scrolls. Naturalism and Idealism are intertwined in a unique way in Papadakis’ works. The icon painter renders the figures in realistic detail, in an icon that is flooded with vibrant and shimmering colors.

Left: Emm. Papadakis, Bloody Trial against Jesus Christ the Saviour of the world (1903), oil on wood. Church of the Presentation of the Theotokos, Chania. Photo by M. Kimionis, Right: Copperplate engraving The bloody sentence of the Jews against Jesus Christ the Saviour of the World, 1760-1775, British Museum

Left: Emm. Papadakis, Bloody Trial against Jesus Christ the Saviour of the world (1903), oil on wood. Church of the Presentation of the Theotokos, Chania. Photo by M. Kimionis, Right: Copperplate engraving The bloody sentence of the Jews against Jesus Christ the Saviour of the World, 1760-1775, British Museum

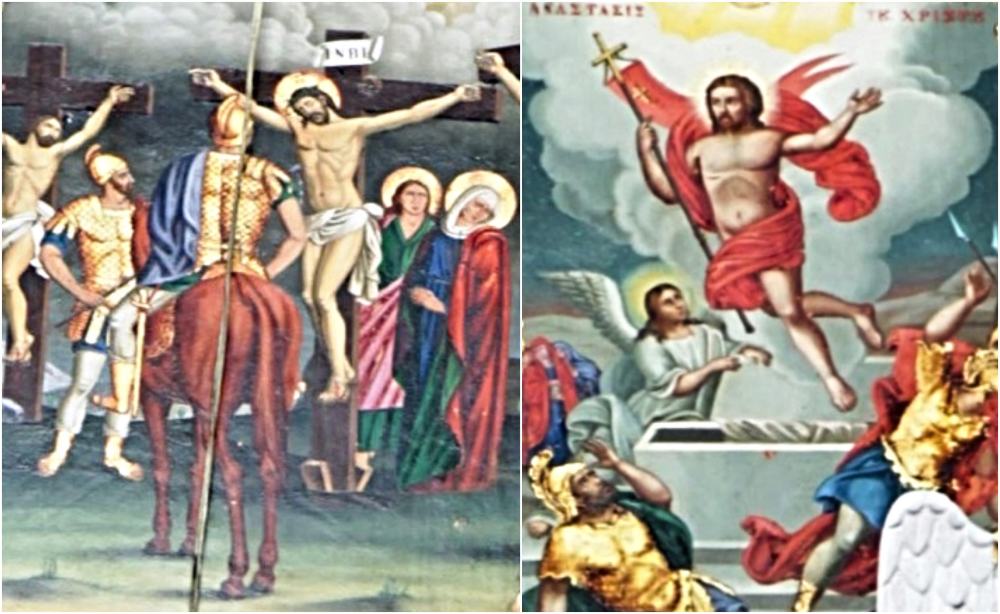

The scene of the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ is depicted in two more western style portable icons that adorn the eastern iconostasis of the Church of Saint Eleftherios, in Gerani, Chania. The icon painter and the date of the works are unknown. In the image of the Crucifixion, Jesus is at the centre of the composition, on the Cross, calm but emaciated from all his suffering. The spearing of Christ by the Roman soldier Longinus is shown once again here. To the right of the Cross the Penitent Thief is portrayed looking pleadingly at Jesus.

The Impenitent Thief is not depicted, we only see his hand. Behind the Cross stands the lamenting Virgin Mary, supported by John. The icon painter adopts the naturalistic approach, rendering the figures with realism. He emphasizes the contrast of light and shadow, prefers bright and harmoniously combined colours, uses oil paint and renders the pictorial space with perspective.

Anonymous, portable icons of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, Eastern iconostasis, Church of Agios Eleftherios, Gerani, Chania http://www.libraryoac.gr/el/

Anonymous, portable icons of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, Eastern iconostasis, Church of Agios Eleftherios, Gerani, Chania http://www.libraryoac.gr/el/

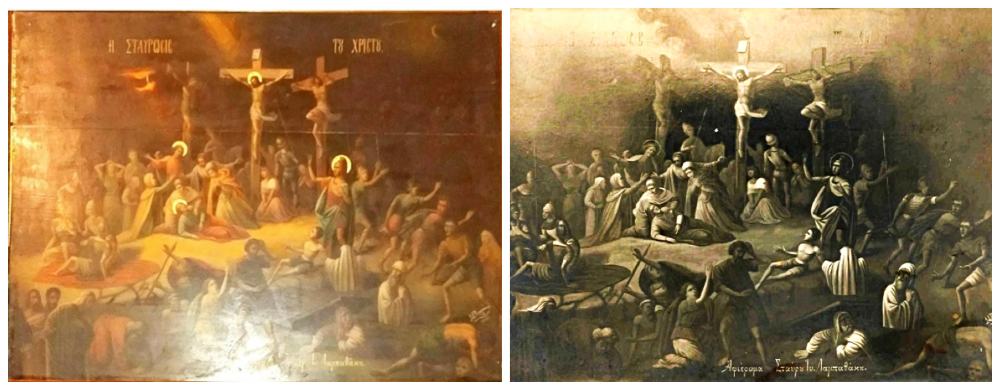

In Crete, and particularly in Chania, the shift towards neo-Renaissance perceptions was reinforced through the instruction of many local icon painters at Mount Athos during the first three decades of the 20th century. In the art of Mount Athos, iconographic styles and the colour scale were influenced by Nazarene painting[13] and western style Russian art. Many icongraphers from Chania, including Stylianos Perrakis[14], followed the western Nazarene path and the western style idiom of Mount Athos that was current. They also adopted the academic approach in the context of the so-called “improvement or correction” of Byzantine art prevalent at the time.

Left: St. Perrakis, The Crucifixion of Christ, 1935, Church of Evangelistria, city of Chania, Markos Perrakis Archive. Right: St. Perrakis, The Crucifixion of Christ, black and white photo of the image, 1935

Left: St. Perrakis, The Crucifixion of Christ, 1935, Church of Evangelistria, city of Chania, Markos Perrakis Archive. Right: St. Perrakis, The Crucifixion of Christ, black and white photo of the image, 1935

In Perakis’ composition of The Crucifixion of Christ, many Western influences are identified in terms of both the materials he uses and the treatment of forms and space. The icon painter depicts the crowds gathered around Christ on the Cross and the two thieves crucified alongside Jesus, along with the various activities on site. The painter also renders the suffering of the Virgin Mary, as well as the episode with the Roman centurion Longinus admitting his faith in the divinity of Christ, astonished by what he witnessed:

“And when Jesus had cried out again in a loud voice, he gave up his spirit.”

51 At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. The earth shook, the rocks split52 and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life.53 They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and[c] went into the holy city and appeared to many people.

54 When the centurion and those with him who were guarding Jesus saw the earthquake and all that had happened, they were terrified, and exclaimed, “Surely he was the Son of God!” (Matt. 51-53, Mark the 38 and Luke 45-46).

The icon of the Crucifixion is an excellent example of Perrakis’ art and it bears his signature. The composition combines colour richness with the dramatization and intensity of movement and gestures. His work is characterized by technical perfection in the execution of the design, synthetic harmony and sensitivity in the use of the colour palette. In terms of style, Perrakis follows the western tradition of the Nazarenes. For the realistic rendering of the composition, he uses shadow and light that gives the composition an academic sophistication. Finally, Perrakis works with oil, replacing the egg tempera of the Byzantine and post-Byzantine tradition.

The return of religious painting to the sources of Byzantine tradition post-1950

The return from naturalistic art concepts to Byzantine standards has been taking place in Greece and Crete since the 1950s, with the catalytic presence, in this direction, of Fotis Kontoglou who cultivated a revival of Byzantine visual hagiography. This was accompanied by the return to the egg tempera technique which replaced oil painting.

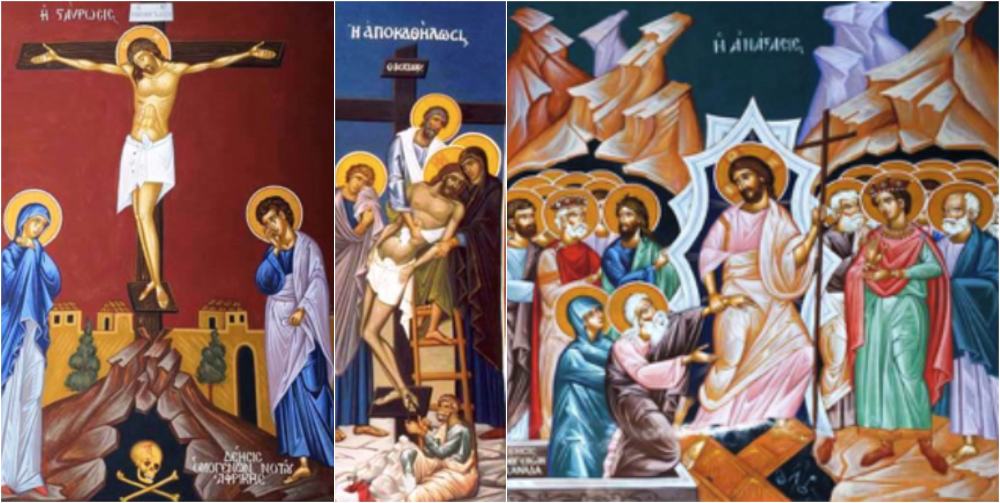

Kontoglou was the point of reference for young icon painters of his time who faithfully followed the standards of their teacher. Among them are the Cretan icon painters Stylianos Kartakis (1912-1988)[15] from the village Plakalona of Kissamos, and Georgios Kounalis, who was active in Chania. They created Byzantine-style frescoes and adorned churches in Crete. We can see the frescoes of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection by Kartakis in the church of Agios Nektarios in the city of Chania, and the fresco of the Deposition by G. Kounalis in the Church of Agios Nikolaos in Souda. Their compositions are distinguished by their meticulous design, colour harmony and elaborate contrasts of warm and cool tones.

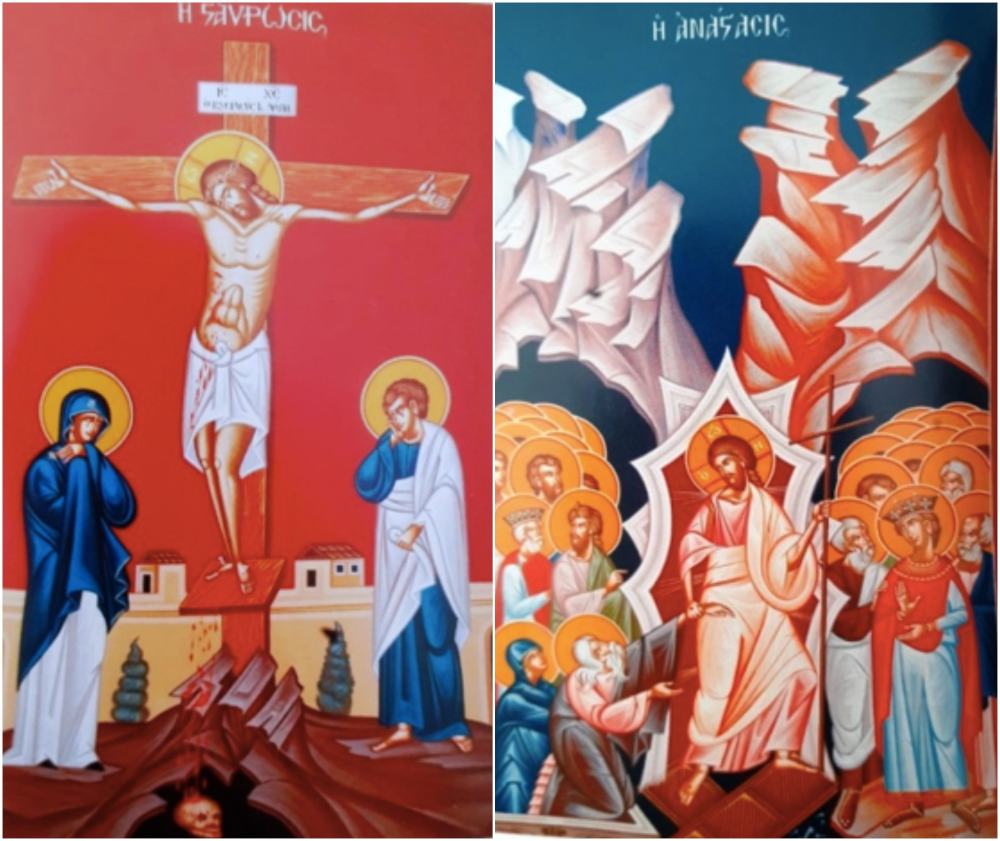

Left: St. Kartakis, The Crucifixion, fresco, Church of Saint Nektarios, city of Chania (source), Centre: G. Kounalis, The Deposition, fresco, Church of Agios Nikolaos, Souda, Chania. Right: St. Kartakis, The Resurrection, fresco, Church of Agios Nektarios, Chania (source)

Left: St. Kartakis, The Crucifixion, fresco, Church of Saint Nektarios, city of Chania (source), Centre: G. Kounalis, The Deposition, fresco, Church of Agios Nikolaos, Souda, Chania. Right: St. Kartakis, The Resurrection, fresco, Church of Agios Nektarios, Chania (source)

In the fresco of the Crucifixion, Kartakis follows the iconographic style of the Byzantine tradition. The figure of the Crucified Christ dominates the centre of the composition, depicted with his eyes closed and head slightly slumped to the right. Although he is dead, he stands on his feet as if he were alive. Dressed only in a loin-cloth, his thin body is overemphasized while his arms are outstretched with his palms open, “as if he were praying and as if he were opening his arms to all people”[16]. “And his legs together, the knees slightly bent, the feet supported on the wood board”[17]. Blood and water are running from his punctured rib. To the right of Christ stands the Virgin Mary looking at her Son, trying to control the expression of pain.

The Divine Drama takes place in front of the walls of Jerusalem. Golgotha is depicted as a rocky place of execution. The cross is placed on the top of the rocky hill, where a cave with Adam’s skull can be seen. As K. Kalokyris notes, the icon painters who narrate the story according to the Byzantine tradition “subject’ realism to the general transcendent dimension of their composition”[18].

The journey into local icon painting ends with a brief reference to the modern painter-iconographer Nikos Giannakakis, a student of Kartakis, from Gramvousa, Kissamos. He studied painting and Byzantine iconography at the Athens School of Fine Arts, as well as mosaic in Florence. In his iconographic painting work he harmoniously combines Neo-Byzantine and Cretan traditions[19].

Left: N. Giannakakis, The Crucifixion, fresco, Church of Agios Panteleimon, Makris Tichos, Chania, 2005. Right: N. Giannakakis, The Resurrection, fresco, Church of the Annunciation, Kastelli, Kissamos, 1992

Left: N. Giannakakis, The Crucifixion, fresco, Church of Agios Panteleimon, Makris Tichos, Chania, 2005. Right: N. Giannakakis, The Resurrection, fresco, Church of the Annunciation, Kastelli, Kissamos, 1992

In the fresco of The Crucifixion, Giannakakis depicts the Crucified Christ in the centre of the composition. His arms are gently extended on the Cross and his palms remain open. The body is naked, but still sacred, lifeless, but rendered as living. He is covered only with a white loin cloth, which, with its beautiful pleating, emphasizes the harmony of the whole composition. The walls of Jerusalem appear in the background, so as not to disturb visually the main subject.

Giannakakis maintains a creative relationship with the Byzantine tradition. The peculiarity of his hagiographic art is due to the finest design and mainly to the intense expressiveness of the look and the movements of the sacred figures, as well as to the use of colour as the main medium of expression that conveys an emotional load[20].

In conclusion

Through this tour of compositions of the Holy Passion as depicted in portable icons and frescos adorning churches in Chania we find that local religious painting is a vivid means of expression of ecclesiastical experience. It is thus strongly influenced by the wider historical context and developments in the arts.

The post-Byzantine icon painters of the 17th century, K. Paleokapas and Th. Poulakis, followed the Byzantine style but also incorporated several Western elements in their works. The iconographic types of the Cretan School were preserved during the Turkish occupation in Crete, although the icons acquired a more naïve expression.

Αt the turn of the 20th century, important icon painters from Chania, such as I. Kalliterakis and Emm. Papadakis, painted portable icons that present an interesting mixture of cultural traditions, a combination of academic, folk and Byzantine elements. Perrakis, a profound connoisseur of the tradition of Byzantine and post-Byzantine art and the Cretan school, soon created a personal artistic idiom in which Western influences were incorporated, mainly of the Nazarene school. The Neo-Renaissance style and academic trends further distanced local religious painting from the traditional Byzantine style. However, this religious art was particularly appreciated by people of faith, thanks to its excellent technical and its idealistic character.

In the 1930s, Kontoglou launched a fierce struggle to restore religious art to Byzantine tradition sources as Byzantine art was considered to be the only one capable of expressing the Orthodox doctrine. Following in the footsteps of Kontoglou, icon painters St. Kartakis and G. Kounalis adopted a purely Byzantine style. Continuing as well as renewing the tradition of the Cretan School, the modern painter N. Giannakakis maintains a creative relationship with the Byzantine and post-Byzantine tradition.

The images of the Holy Passion presented in this studyeloquently mark the course of Orthodox painting in Chania and allow the faithful to perceive and experience religious art both aesthetically and worshipfully: the transition from the Crucifixion to the Resurrection is at the foundations of the Christian religion. Death and Life coexist on the Cross. Have a Happy Easter!

Translated by Marianna Varvarrigou and Magda Hatzopoulou (Intro image: Stylianos Perrakis, The Crucifixion of Christ, 1935, Church of Evangelistrias, Chania city, Markos Perrakis Archive)

[1]Alevizu Deniz-Chloe, The Artists’ Crete – 19th 20th century: Hagiography – Painting – Sculpture, Dokimakis Publications, Heraklion, 2010, p. 20.

[2]See Kalokyris, K., Twelve festivities, Religious and Ethical Encyclopedia, vol. 5, Athens, 1964, p. 752.

[3]The copperplate engravings of Jan Sadeler depict the lancing of Jesus on the Cross & the tearing of his clothes.

[4]For the Flemish standards in Post-Byzantine painting and the iconography of the Passion, see Rigopoulos Ioannis, “The Crucifixion of Christ and its Flemish Standards”, available at https://www.academia.edu

[5]Th. Poulakis mentions Chania in Crete as his place of origin on the icon Epi Si herei (All creation rejoiceth in thee).

[6]See Lydakis St., Dictionary of Greek Painters and Engravers, Melissa Publications, Athens 1976, p. 362. See also Rigopoulos, Ioannis K., The iconographer Theodoros Poulakis and the Flemish copperplate, published by Grigoris, 1979.

[7]For biographies of the iconographer priest I. Kalliterakis, see Graikos, N., “Academic trends of ecclesiastical painting in Greece in the 19th century. Cultural and iconographic issues”, Doctoral Thesis, Thessaloniki 2011, p. 574.

[8]Graikos, N., op. cit., pp. 275, 547. In his doctoral dissertation, N. Graikos ranked the Reverend I. Kalliterakis among the “Academic hagiographers who paint in a western way, but also use folkloric elements.”

[9]For biographical information about the iconographer priest I. Kalliterakis, see Alevizu Deniz-Chloe (2010), 103, (pp. 83, 84).

[10]See Jean – Baptiste Jouvenet, La déposition de la croix, Louvre. SeeGraikos, N., (2011), p. 547

[11]See the icon of The Deposition by St. Stavrakis (18th century) at the Benaki Museum.

[12]See copperplate engraving The bloody sentence of the Jews against Jesus Christ the Saviour of the World (1760-1775), British Museum. See also Frederick Kemmelmeyer, The Bloody Sentence of the Jews Against Jesus Christ the Lord and Saviour of the World (1788-1799)

[13]See Georgiadou Kountoura E., “Religious issues in Modern Greek painting, 1900-1940”, doctoral dissertation, Thessaloniki, 1984, p. 24. See. also Alevizou, (2010), 60.

[14]For biographical and other data on the hagiographer S. Perrakis, see Alevizou (2010), p. 213. See also Grigorakis Michalis, “Chania and their visual artists”, Provoli publication, Haniotika Nea newspaper, 1999, p. 36: “St. Perrakis was born in 1875, was the son of an iconographer, worked extensively with oil and left many works with a distinctive combination of colours. His work bore influences at times from the West and others from the Byzantium. He was a noted artist for a considerable time.”

[15]For biographical and other data about the icon painter Kartakis, see Lydakis St., (1976) p. 167 and Alevizou, (2010) pp. 265 – 268

[16]Kontoglou, Fotis, Expression of Orthodox Iconography, vol. A, Papadimitriou Publishing, 2000, p. 174

[17] Ibid.

[18]K. Kalokyris, The paintings of Orthodoxy: Historical, Aesthetic and dogmatic interpretation of Byzantine Painting, Pournara publications, 1972. p.139

[19]See Giannakakis Nikos, To the Glory of God: Neo-Byzantine and Cretan History, Prefecture of Chania, 2005. The images come from this book

[20]Filis Giannis, Nikos Giannakakis: I am an icon painter, Regional Unit of Chania, Chania, 2015, p. 47