Nestled in the mountains in the south of the Greek island of Evia, the small, remote village of Antia is known for its unique whistled language, used for centuries by its now ageing population. But what is a whistled language?

Whistled languages in the world

A whistled language is a system of communication using whistles, encountered throughout the world but only in environments where whistling is more effective compared to ordinary speech (mainly mountains and dense forests). In 2009, the Silbo Gomero, a whistled language from La Gomera (Canary Islands), was inscribed by UNESCO on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO, the Silbo Gomero is the only whistled language in the world that is fully developed and practised by a large community (more than 22,000 inhabitants). In 2017, the whistled language of Kuşköy (Turkey) was also inscribed on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.

As of 2018, as many as 70 whistled languages had been recorded around the world, including the Mazatec and Chinantec whistled languages in Mexico, the Gavião in the Amazon, the whistled languages of the Akha and the Hmong in Southeast Asia, the Béarnais Ossalois in the Pyrenees and others. It should be noted that each of these languages is not an independent language but an extension of the local dialect. Research is underway (Meyer 2004, Carreiras 2005, Lopez 2005) to better understand the intimate mechanisms of this whistled speech while linguists such as Julien Meyer have created networks of intercultural collaboration on the subject.

World map of the most documented whistled forms of languages (J. Meyer and B. Gautheron [Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics])

World map of the most documented whistled forms of languages (J. Meyer and B. Gautheron [Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics])

According to the conclusions of existing research, the whistled speech relies on phonetic elements of the original spoken language to convey information at a distance or in a noisy environment, while providing high intelligibility of the sentences under these circumstances.

A comparative study of spoken speech, shouted speech and whistled speech has shown that whistling is an effective way of transmitting sound against a noisy background as the communication distance increases. It therefore allows human speech to naturally develop properties which form a real telecommunications system. (Meyer, 2005)

From the antiquity to the present day

Already in the 5th century BC. J.C, in Melpomene (book IV of The Histories), Herodotus mentions the existence of Ethiopian troglodytes who “speak like bats”.

Several navigators of Antiquity also report that the Guanches, the aboriginal inhabitants of the Canary Islands, used, in addition to their usual speaking, a whistled language which enabled them to communicate from valley to valley at a distance of several kilometers.

The classic Chinese text Xiaozhi (c. 8th century AD by an anonymous author, later identified as Judge Sun Guang), describes the art of transcendental whistling, an ancient Daoist technique. Its title could be interpreted as “Principles of Whistling” or “Directives on Whistling”. The Xiaozhi preface begins with a definition that semantically expands xiao from “moan; call out” and “call back (a soul)” to a new meaning of “communicating (with the Daoist gods and spirits)”. This is one of the earliest works of phonetics: it describes how to practice whistling and also gives twelve specific whistling techniques, with directions regarding the placement of the tongue and lips, control of breathing etc.

The first historical undisputable historical proof of the existence of a whistled form of a language dates back to the written testimony of two Franciscan priests who accompanied the French explorer Jean de Béthancourt who set out to conquer the Canary Islands in 1402. In their logbook, published under the title Le Canarien, Bontier and Le Verrier mention that the islands’ inhabitants spoke “with two lips as if they had no tongue”. Thanks to other testimonies, we now know that what they had witnessed was a whistled form of the local Berber language then spoken by the Guanches (Meyer, 2015).

The whistled language of Greece: The story of Antia

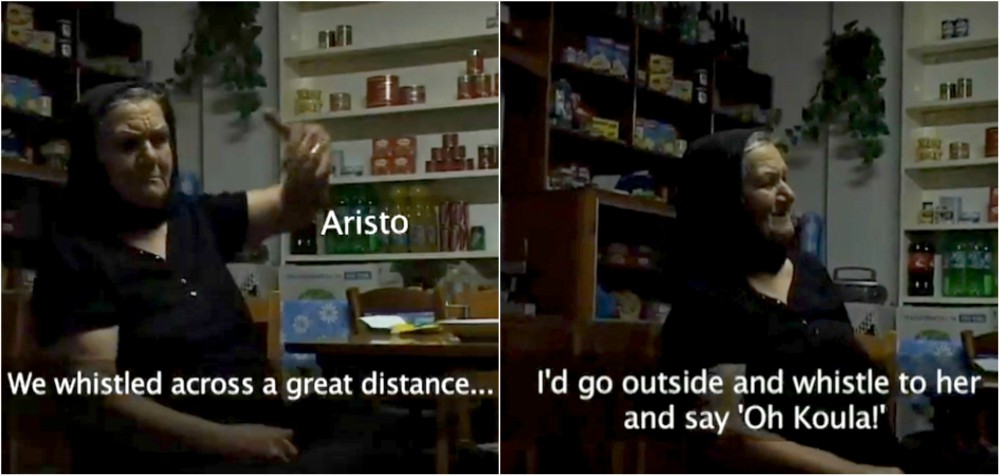

The only whistled language in Greece (and one of the only two in Europe) is still used in Antia, a small village in the south of the island of Evia (Euboea), where the locals call it sfyria (from the Greek sfyrizo “to whistle”).

Sfyria has a centuries-long history, and has always been used by the inhabitants of mountain-encircled Antia, especially the shepherds, who are believed to have used the whistled language to communicate with each other and with their families across enormous distances. The high-pitched sound combined with the mountainous terrain helped the sound travel even further.

General view of Antia, Source: (Meyer, 2005)

General view of Antia, Source: (Meyer, 2005)

However, the actual origin of this form of communication remains uncertain; according to one theory, it originates from Persian soldiers who had been guarding Greek prisoners in the Karystos area, and later fled into the highlands following their defeat in the Battle of Salamis in 480BC. These soldiers would then have developed a whistled language to avoid revealing their position and the content of their discussions, a practice subsequently picked up by the locals. Another theory suggests that the language was created by the inhabitants of Evia in the Middle Ages, as they moved inland to protect themselves against Sicilian and Venetian pirates. According to this theory, they invented this method to warn each other of further attacks and hide.

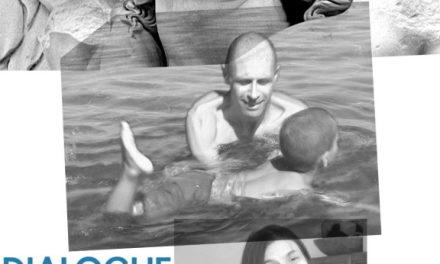

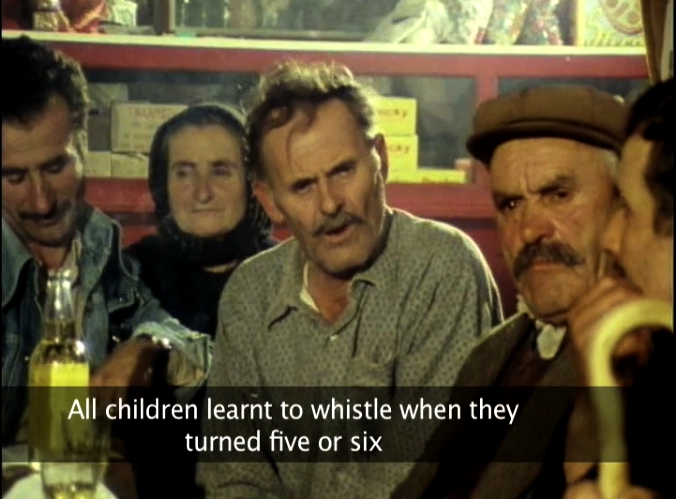

Source: The Village that Whistles by Katerina Zoulas (2010)

Source: The Village that Whistles by Katerina Zoulas (2010)

According to Dimitra Hengen, a Greek linguist who spoke to BBC Travel, sfyria is effectively a whistled version of spoken Greek, in which letters and syllables correspond to distinct tones and frequencies. Because whistled sound waves differ from speech, messages in sfyria can travel up to 4km across open valleys, roughly 10 times farther than shouting.

What is striking is that sfyria was only discovered by the rest of the world in 1969, when an aeroplane crashed in the mountains behind Antia. While the crew was searching for the missing pilot, they witnessed the shepherds exchange messages across the canyons in this way.

Source: The Village that Whistles by Katerina Zoulas (2010)

Source: The Village that Whistles by Katerina Zoulas (2010)

There are no more than six people, among the only 37 remaining inhabitants of Antia, who can still “speak” -or rather whistle- this language today. Although it has not yet been registered in the UNESCO heritage list, sfyria is considered to be older and more structured compared to many other whistled languages, while also being the most critically endangered. In fact, according to the Unesco Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, no other language in Europe – whistled or not – has fewer living speakers than sfyria.

Originally written for Grèce Hebdo by Magdalini Varoucha in French & adapted into English by Nefeli Mosaidi

Also watch

The Village that Whistles, Documentary by Katerina Zoulas (2010)

Greek Odyssey, documentary series by Joanna Lumleys (2011)

Whistle language speakers (Alpha omega translations)

Greece’s disappearing whistled language (video) and article by Eliot Stein, BBC Travel (2017)

TAGS: HERITAGE