Greece has long been identified as synonymous with unique archaeological sites and beautiful summers, yet maybe the country has more to think about while trying to build a new image in the post-COVID-19 world and its globalised challenges. This was one of the points stressed during the first PD Talks (Public Diplomacy Talks), launched on June 18 by the Secretariat for Public Diplomacy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs. The shaping of a reliable country image passes through listening and dialoguing, building long-term strategies, talking about realities and understanding complex identities, encouraging cooperation and exchange, rethinking modern history, asking rather than answering, Professors Nicholas J. Cull (University of Southern California) and Stathis Kalyvas (University of Oxford), stressed, among others, while addressing the questions during the first online “Greek PD Talks” titled “Turning the Tide: How to reverse a negative image – The case of Greece” (June 18th, 2020), organized by the Secretariat for Public Diplomacy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and moderated by Reuters correspondent Renee Maltezou.

Opening remarks by Greek Foreign Ministry officials

Inaugurating the forum, which is meant to kick off a series of events on public diplomacy topics, Deputy Foreign Minister for Diaspora Greeks, Konstantinos Vlasis, stressed that public diplomacy is an important aspect of international politics and a state’s diplomatic outreach. Yet, perceptions being dynamic and volatile, promoting one’s image demands constant efforts and specific strategies.

Inaugurating the forum, which is meant to kick off a series of events on public diplomacy topics, Deputy Foreign Minister for Diaspora Greeks, Konstantinos Vlasis, stressed that public diplomacy is an important aspect of international politics and a state’s diplomatic outreach. Yet, perceptions being dynamic and volatile, promoting one’s image demands constant efforts and specific strategies.

The host of the event, Secretary-General for Public Diplomacy, Religious and Consular Affairs Kostis Alexandris said that the forum, scheduled to take place on an annual basis, aims at exchanging views and best practices on public diplomacy issues and then referred to Greece’s image in the recent years as covered by the international media. Leaving behind a decade long austerity & financial crisis, 2019 is the first year in a decade when positive comments outweigh negative ones, Mr. Alexandris said, based on data analyzed by the Ministry. Also, effective COVID 19 management by Greece so far, has brought positive media coverage to the country, uplifting its international image. So one of the main questions is how to maintain this momentum, said Mr. Alexandris, stressing that Secretariat’s goal is to leave behind times of introversion and bring forward the image of a country that innovates, grows, and regains its active role internationally. [Inaugural speech by K.Alexandris available here]

Nicholas Cull: Public diplomacy is about listening and interacting based on realities

Nicholas Cull: Public diplomacy is about listening and interacting based on realities

In his introductory remarks, Professor Nicholas Cull stressed that reputation is part of a country’s security, and this is what makes public diplomacy important. Yet, in his view, this is only built on partnering and working with others.

As regards the foundations of public diplomacy, he said that the public is central to foreign policy, and explaining the reasons why we live in the era of “reputational security”, in the sense that countries’ images can play a role in shaping international relationships.

Yet, he stressed, public diplomacy today is quite different than in the ’90s when the challenge for a state was to tell a good story about itself and communicate it. Nowadays it is very important to be engaging with the public and empower other people or entities to speak on a state’s behalf. “So we’re moving to a public diplomacy based on empowerment and collective, team activities” he stressed, as “the problems we face such as the virus, mass migration climate change, etc, are too big for any country to deal with on its own.”

Laying out his view on the main issues coming up within public diplomacy strategies, Professor Cull stressed the failure to listen (i.e. twitter accounts of Foreign Ministries or embassies’ accounts not following anybody) and failure to cooperate with other countries, while also stressing as problematic the use of public diplomacy as a tool for governments’ domestic promotion. Public diplomacy strategies shouldn’t serve for domestic political purposes, but should “engage foreign audiences for their own shake, not just to seek legitimacy for whatever the government is doing at home”, professor Cull said.

Another issue when deciding on public diplomacy strategies is the tremendous mismatch between the historical identities people have and the translational realities they actually live in. In a world of mobility, where people immigrate and may have complex multi-state identities, we need to think international relationships from this angle too, not only through the nation-state prism, he said.

His next point was that “public diplomacy cannot be all about you, it can’t be all about a government saying «my country is great»: it has to be about addressing issues, addressing shared problems” as he put it while stressing “I see a great danger in Foreign Ministries talking about «winning»: relationships are not about winning, they need to be about mutual success. In this respect, the ability to collaborate could be one of the goals of a public diplomacy strategy, he said, concluding this chapter of his presentation with general points.

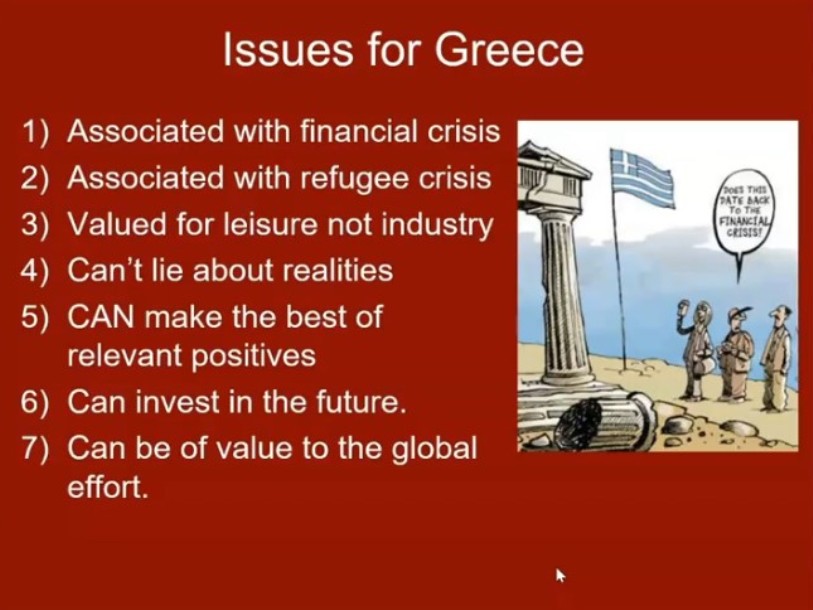

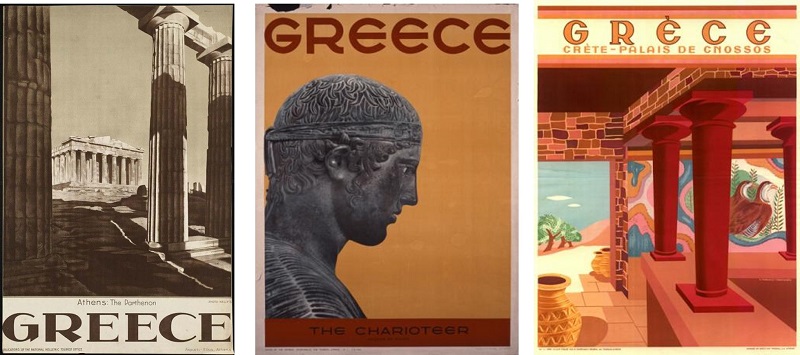

Passing on to issues concerning Greece’s image, in particular, Professor Cull found problematic that the country is mainly associated with the financial and refugee crisis, while valued mainly for leisure: “Positive images of Greece are mainly associated with beaches and historical monuments; we are not thinking of Greece, for example, as a country helping solve shared problems in the world or as a reliable partner on global issues”, he characteristically said, adding that Greece cannot lie about realities: there are problems in the country that have to be talked about, while also trying to make the best of relevant positive facts. Looking for long term strategies, and ways in which Greece can be of value to a global effort trying to solve global matters that people care about, are some ideas for Greece’s image building, according to Cull.

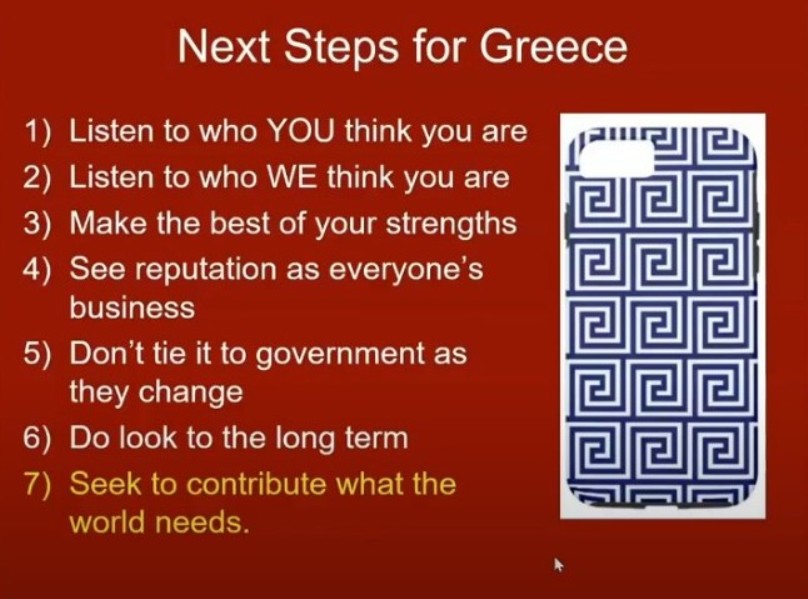

In this context, the next steps for Greece’s public diplomacy should be about listening (both in Greece and abroad) and basing its image on the long term issues, while also building country-specific strategies. For Cull, efforts should also be made to involve different communities as public diplomacy advocates while not linking the national strategy to governments, as governments change. “To me, the best idea for a public diplomacy strategy for Greece is to seek out and contribute to the things the world needs right now, look at the big issues and think about which parts of these issues Greece can be seen to make a difference in,” he said.

Giving some examples, as part of brainstorming, he said that essential values could be presented in new ways or less known aspects of culture be showcased (Pnyx as the birthplace for democracy or Kos as the birthplace of Hippocrates, etc).

As regards the new media, he said that countries and foreign ministries often fail to segment their social media with topic-specific feeds. Professor Cull concluded that public diplomacy offers “no magic answers”; it is a long-term strategy building process, that starts with listening and engaging over time.

Stathis Kalyvas: Greece as a pioneering nation and center of a balanced life

Stathis Kalyvas: Greece as a pioneering nation and center of a balanced life

Professor Stathis Kalyvas started by saying that any conversation on Greece’s image should start from its own people’s self-understanding. He went on challenging the idea that Greece’s image during the financial crisis was an entirely negative one, saying that the country was also seen with some sympathy, as a “victim” of policies imposed by the Eurozone, Germany, international capitalism, etc. By the same token, Greece’s image during the refugee crisis was also somewhat positive, identified with people being very generous and helpful; yet this wasn’t entirely truthful since most Greeks saw refugees positively only because they thought they were only crossing the country, Professor Kalyvas stressed.

All the above were said in order to emphasize the element of contradictions when talking about national images, Professor Kalyvas explained, as in his view there is not a homogenous positive/negative image of Greece -even when we think there is –yet, he recognized, there is work still to be done on the actual negative dimensions of Greece’s image.

Passing on to the Covid-19 crisis, Greece projected effectively the narrative of good management and generated a positive image in the international media. But the problem in Kalyvas’ view is that this image is not connected to a particular aspect of Greek identity and thus it cannot be long-lasting. The reason is that “performance and effectiveness are not necessarily Greece’s strong points and with an economic crisis coming in, this will threaten whatever positive stems from the pandemic. So I would argue, COVID in itself is not necessarily a «golden ticket» for Greece to move forward.”

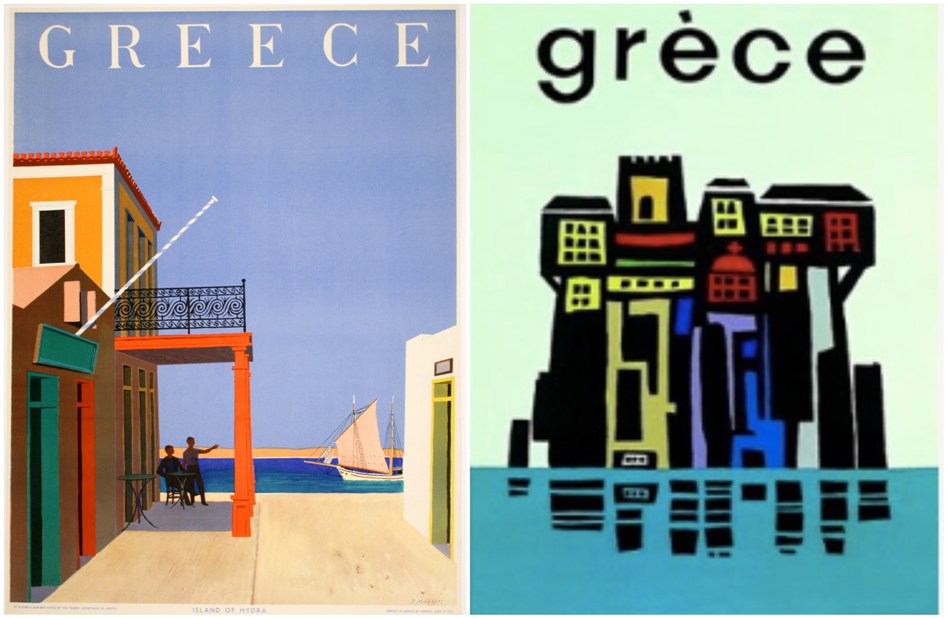

Posters by Yannis Moralis. Source: GNTO (Greek National Tourism Organisation)

So what could be the foundation for rethinking Greece’s image?

In Professor Kalyvas’ view, Greek identity should go beyond its two pillars, archaeology and tourism, and the new core of public diplomacy should be linked to a self-understanding of what Greece today stands for, from a global perspective. In this context, he mentioned two ideas worth considering as foundations of a new Greek identity:

A) The first one relates to a reassessment of modern Greek history focusing on the pioneering dimension (that has been emphasized by historians like Mark Mazower): Greece is one of the very first post-colonial nations which have actually made it to the core of modern European nations, -not completely, but it did succeed.

B) The second one relates to the ability to deliver services (such as education) in a setting that is ideal due to a deeply rooted sense of balances, a life that goes back to the antiquity ideals of «metron». Greece is a place where people come to re-center, to find themselves, to “reconnect”, not only with themselves but also with nature and with others.

Summing up, Professor Kalyvas argued that the element of a pioneering new nation on one hand, and that of balance, on the other, could constitute two poles of a new image that could become the basis of a variety of interventions and exchanges globally.

Greek National Tourism Organisation Posters. Source: GNTO

Q&A Session

Answering a relevant question, professor Kalyvas said that there are aspects of handling Covid19 in Greece that could be highlighted, for example, the flexibility and down to earth approach of its people, which again goes back to his idea of balance, in the sense that people in Greece can manage effectively something which is very adverse. “It is very important to have a general narrative, from which specific narratives on issues can emerge”, he stressed. Professor Cull agreed, adding “the point is to be known about things that are real and true.”

About the 2021 bicentenary from the Greek revolution, Kalyvas said it is a unique opportunity to talk about less-known aspects of Greek history. Regarding the role websites and social media in shaping a country’s image, Cull said we tend to overemphasize their value, whereas the most important aspect in building a reliable image is talking about realities. “Although social media do contribute in shaping and changing images, I believe we shouldn’t overstate their role. It is one of the things you can work with, but do not think they can work miracles” he said.

Watch the video of the event here: https://pdtalks.dmh.gr/

Read more: Join the first “Greek Public Diplomacy talks” webinar: the new initiative of the Sec-Gen for Public Diplomacy; “Public Diplomacy in Practice”: Inaugural seminar of the Secretariat General for Public Diplomacy; Sec-Gen for Public Diplomacy, Religious and Consular Affairs Constantinos Alexandris on building the new image of Greece; The practice of Greek Public Diplomacy and its contribution to the country’s image abroad

Text by Magdalini Varoucha, edited by Florentia Kiortsi.