Nick Malkoutzis is the editor of MacroPolis, an analysis service providing daily information on political, economic and social issues related to Greece. He was the deputy editor of the English Edition of Kathimerini, a leading Greek daily, between 2004 and 2016. He currently writes a weekly column for the newspaper. His work has also appeared in Bloomberg Businessweek and other international publications such as Die Zeit and The Guardian. He has written several papers about Greece and the crisis for the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Germany. In 2015 he was awarded the Ernest Udina prize for European journalism.

Nick Malkoutzis spoke to Greek News Agenda* about his long experience as a journalist, MacroPolis, his latest venture, how challenging is to practice independent journalism in Greece, the way the Greek crisis has been presented in the Greek and international media as well as about the current state of affairs in Greece and the country’s future prospects.

You have been the deputy editor of the English Edition of Kathimerini, while your work has also appeared in Bloomberg Businessweek and other international publications. Tell as a few things about your experience as a journalist for both the Greek and international media.

The last few years have been an incredibly intense, worrying, enlightening and exhausting period. As for many of my colleagues, this has entailed much hard work and personal sacrifice, regardless of whether you are representing local or international media.

Writing for outlets outside Greece, it has been strange to see a country that nobody used to pay much attention to thrust into the international spotlight. Naturally, this has led to some misperceptions that it has been important to address through balanced and accurate reporting. On the domestic front, the sheer pace and frequency of developments has been incredible. There have been times when it was impossible to keep up with everything that was going on. I think our colleagues abroad who are now covering the fallout from Brexit are getting a taste of what it was like. Saying that, I’m very appreciative of the knowledge that I have acquired and the friends that I have made along the way. It has been great compensation.

In 2013 you founded MacroPolis, an analysis service providing daily insight on key political, economic and social developments in Greece. Three years later, how things stand with your venture? Which are the main challenges you have faced so far?

Our aim with MacroPolis was to achieve two goals: a) To provide the context and data needed to make sense of developments in Greece and b) To become a trusted source of analysis. I think that we have done very well on both fronts thanks to the efforts of a very talented and experienced team.

However, starting anything independent in n negative business environment, like the one we have in Greece, is a real challenge. We face the same complications that other start-ups here do, which include the difficulties accessing funding, the increases in taxes and the significant levels of bureaucracy.

Thanks to the trust placed in us by our subscribers we have been able to meet these challenges and keep building on what he have achieved. Getting people to put their faith in you as reliable source of information involves a tremendous amount of hard work and application. It is difficult sometimes to be the one speaking in a calm, steady voice when everyone around you is shouting but that’s exactly what MacroPolis is there for. There has been a positive response to this approach and this gives us great encouragement for the future.

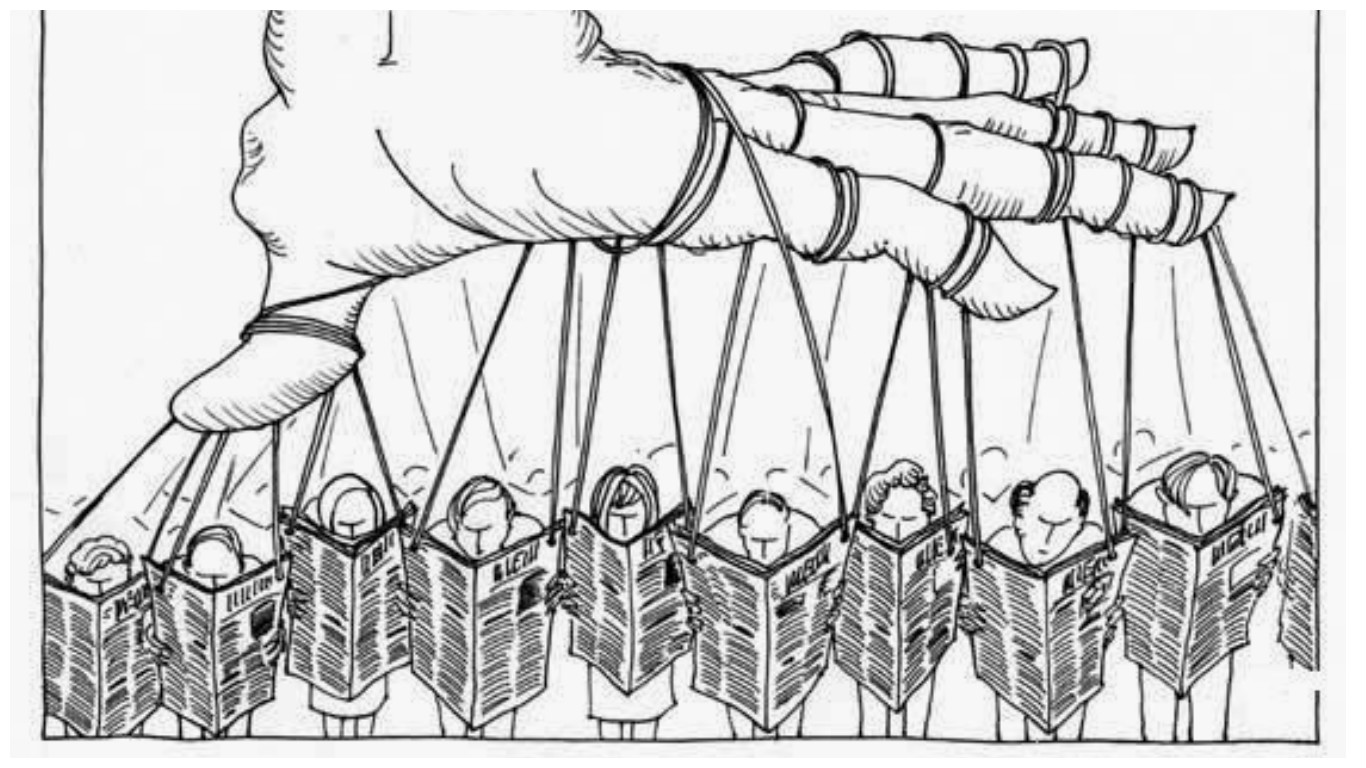

You have stated that MacroPolis’ mission is to “provide its readership with impartial and pertinent analysis that puts Greece in perspective”. How challenging is to practice independent journalism in Greece?

Although what we do is analysis rather than journalism, I think the principle is the same. There are two key elements to being independent – one is the financial aspect, the other is editorial.

Maintaining your financial independence, particularly in the current testing circumstances, is obviously very difficult. In our case, since our content is aimed at an audience that follows Greece for professional reasons, it was important that we made it clear to subscribers that what we write is not open to the influence of business or political interests. That’s why we intended from the start to adopt a subscription model. In this way, we felt that we could secure our financial and editorial independence.

Saying that, I would like to point out that just because a media outlet is independent, or defines itself as independent, does not necessarily also mean that it is accurate or worthwhile. There is a lot of excellent output from the mainstream media and some very poor content from independent outlets, as well as the reverse. This is the case in other countries, not just Greece. Quality and independence do not necessarily go hand-in-hand. You have to fight separate battles for them.

During the last few years Greece has received wide media coverage due to the economic crisis and more recently the refugee/migrant crisis. How has Greece been presented in the international media? Which are the main differences compared to the Greek media coverage?

Greece is a small country that has made a lot of noise in recent years. Separating the signal from the noise has been the big challenge for foreign journalists who had to follow developments. There are a number of reasons that the Greek crisis has been a difficult one to cover: Greece is a complex country with many competing interests, it experienced an economic collapse whose magnitude was unprecedented for a developed country, the management of the crisis involved lots of actors with contrasting motivations and interests (Greece, European institutions, eurozone member states, IMF), and it was a crisis that stoked strong passions and arguments over political ideology, economic thinking and even visions for the European Union.

As a result, the quality of the coverage has been mixed. Some of the reporting and analysis on Greece has been excellent but a lot of it has been restricted to very stale narratives that either skimmed the surface of what was happening or fitted a particular pre-determined view. Similarly, the domestic media has also had a mixed time in covering events. While there has been excellent, probing work, there has also been a lot of coverage whose sole purpose was to strengthen the “pro-memorandum” or “anti-memorandum” argument, which has created such a cleavage in Greek society over the last few years.

You have stated that “to know [Greece] thoroughly is impossible; to understand it requires genius; to fall in love with it is the easiest thing in the world”. In your estimate, how things stand at a political level at the moment? Which may be the country’s future prospects?

While I would very much like to take credit for that quote, it does in fact belong to the late American author Henry Miller, who spent some time in Greece. I think it perfectly sums up what a lot of people feel about the country, regardless of whether they are Greek or foreigners, which is a mixture of frustration and perplexity that is overcome by an enduring passion for the place and its inhabitants.

I don’t expect that Greece will become any more straightforward in the coming months or years. Despite completing the latest bailout review, the government has a tough task ahead of it. It needs to implement further structural reforms and keep public finances on track, while hoping that the economy will start to recover. At the same time, the eurozone’s relationship with the International Monetary Fund has yet to be defined. Given that Greece’s lenders have yet to detail their plan for debt relief, clarity regarding the IMF’s future role is an important piece of the puzzle for Athens.

In this rather unstable environment, Brexit was the worst thing that could have happened. While it may yet lead to a faster and deeper integration of the eurozone, which would protect Greece to some extent, I expect that it will trigger very conservative reflexes among policy makers. I don’t think anybody will be willing to take the risk of supporting further burden-sharing and less sovereignty due to fears about giving the nationalists and populists in their countries more ammunition.

Also, we should not forget that the Greek economy faces a long, hard slog ahead of it. The IMF, for instance, expects that it will take around 30 years for the unemployment rate to drop to single digit figures. This will obviously have a painful social impact as well. So, the onus is on Greek decision makers to develop a clear vision about the way forward, particularly when it comes to growth, innovation and job creation. Greece has many talents and much potential. They have to be harnessed so we can start putting this period of devastation behind us.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: CRISIS | GOVERNMENT & POLITICS | MEDIA