George Rorris is one of the most important representatives of figurative art in Greece. Born in the village of Kosmas of Kynouria (Arcadia, Peloponnese) in 1963, he was a student of Panagiotis Tetsis and Yiannis Valavanides at the Athens School of Fine Arts (1982-1987).

He went on to pursue his studies at the Parisian École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts under Leonardo Cremonini (1988-1991) thanks to a Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation scholarship coupled with a Bakala Brothers Foundation scholarship.

In Athens, George Rorris collaborated with the cultural centre Apopsi from 1996 to 2002. In 2002 he began working with the Art Group “Simio”, where he tutors painters. In 2001 he received the Academy of Athens award for new painters under the age of 40. In 2006 the Alexandros S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation conferred an honourable distinction for his work. He maintained a permanent collaboration with Medusa Art Gallery, in Athens, since his first solo exhibition there in 1988, until 2017. Works by him can be found in public and private collections. He lives and works in Athens.

George Rorris (Photo ©Elissavet Moraki)

George Rorris (Photo ©Elissavet Moraki)

The works of George Rorris have been described as theatrical; the way he approaches people and objects is said to be clearly evident in the portrayal of his models. As he has said, he is interested in leaving behind historical records of his own time for future generations, thus paying attention to details that put the painting within a particular historical context.

For Rorris, a painting is the sincere revelation of one’s soul – it is thus no wonder that his works are believed to start a dialogue with the viewer, evoking sensations through his faithful depiction of the visible.

In the summer of 2021 (4 July – 3 September), the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation presents a retrospective exhibition dedicated to George Rorris, by at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Andros. The large retrospective, titled The Nobleness of Purity, will span 35 years of creation by “one of the most important visual artists of his generation”.

On this occasion, the acclaimed artist spoke* to Greek News Agenda about his childhood, his introduction to the world of art, the man who played a key role in his decision to study at the School of Fine Arts, as well as about the way that the art of painting can “decodify the mysteries of nature by depicting them”.

Large study in cadmium red, 1987 – 1988, oil on canvas

Large study in cadmium red, 1987 – 1988, oil on canvas

Mr. Rorris, you are one of the most important representatives of representational art in Greece. What motivated you to choose painting as a means of expression?

Thank you for the question. I believe the reasons motivating someone to choose to paint are different for every individual. Painting was for me a means to change my destiny; something I knew not then but I know now. I was born in a village and I had a lovely childhood. I have many memories of a country that belongs to the past. I was born into a rural family and grew up with my grandfather, my grandmothers and my siblings, without facing serious adversities or disparities in the small closed environment of the village, where we all knew each other. I did not have any direct artistic stimuli that would come from visiting a museum for instance, and almost no indirect with high art either through, let’s say, the wonderful Melissa publications on Greek artists that everyone seemed to have at home.

I was not acquainted with the works of Gyzis or Vryzakis, save for some black and white images in our history book of a work by Leonardo Da Vinci, and one probably by Delacroix, The Massacre at Chios. However, I regarded the images in our schoolbooks as art, especially those in our first grade readers. In our exercise books for writing, we had to draw a picture on the top half of the page that was blank for this purpose and write at the bottom half the few sentences given us by the teacher.

In the first months of first grade, my mother, who had some drawing skills, would draw the pictures for me in the evenings after she got home from working in the fields and I was sleeping, in order to help me. When I’d get up in the morning my exercise book would lay open on the table with her drawing on the page right above my writing exercise.

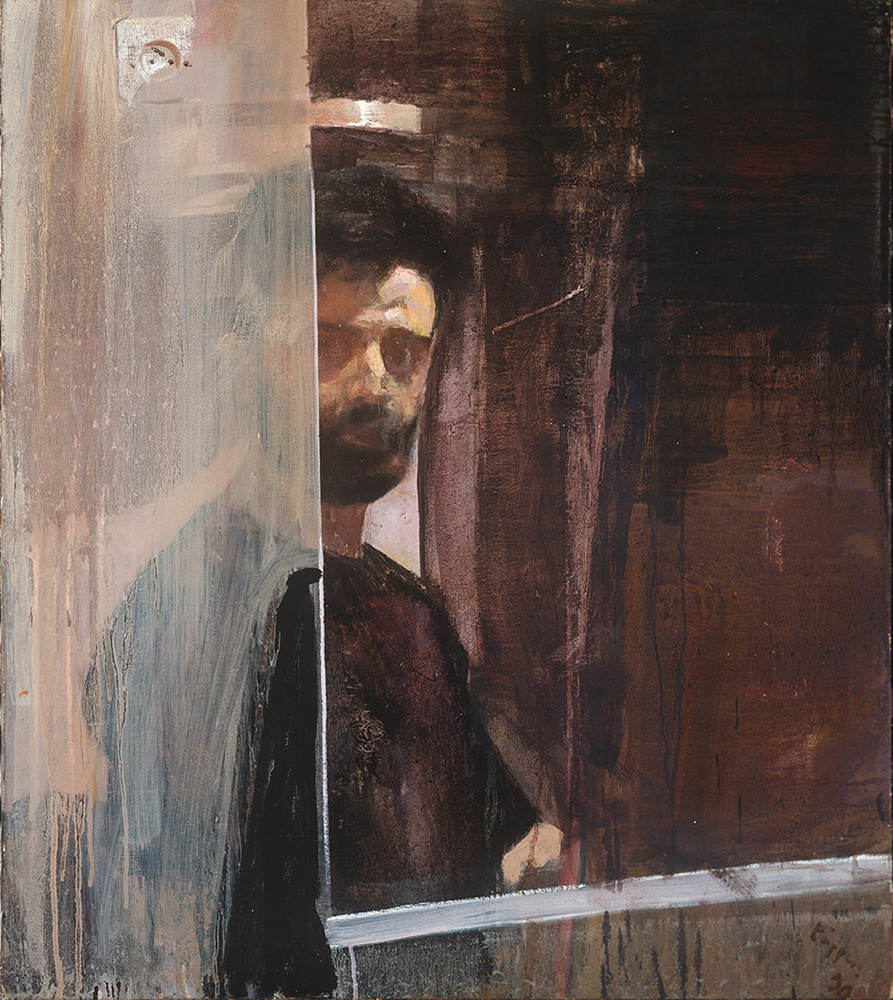

Half Self Portrait, 1989 – 1990, oil on canvas

Half Self Portrait, 1989 – 1990, oil on canvas

When I think of this in hindsight, I can see that it was in a way a “small miracle” as, without realizing it at the time, I knew that the drawing, while not as refined as those in my books, was nonetheless unique. The uniqueness of a work of art is a crucial aspect of art. The drawing existed in my exercise book alone, not in those of my friends; only in mine.

At the end of the school-year, sometime in April – May, my parents had to come to Athens for a medical visit. I stayed back with my grandparents and there was no one to draw for me, so I had to draw on my own. My mother has kept that exercise book. I drew a swallow’s nest. Crude, hesitant but it was a swallow’s nest. That was probably one of the first things I ever drew, and I continued to do so henceforth. I enjoyed it and the grown-ups around me commented that Ι had drawing skills. I would copy drawings from our readers using pencil and paper, as I had no other materials.

Given that our schoolbooks were largely illustrated with black and white engravings, I did not feel the need to obtain colored pencils in order to draw. A pencil was just fine. My way of drawing was simple but in the end my drawings bore a resemblance, let’s say, to the illustrated images of Kolokotronis or Katsantonis. The subject matter of many of those images in our textbooks was related to the Greek War of Independence (1821) or Greece in World War II, aiming to inculcate patriotism in children and instill pride in the past; other images obviously related to life in peacetime as well.

Young woman with painted lips, 1997, oil on canvas

Young woman with painted lips, 1997, oil on canvas

But the main reason I chose to paint was not related to the drawing skills I had shown. It was due to the encouragement of an authority figure, a person whose views I respected: that of my Greek language and literature teacher, a man of knowledge and culture, who perceived my inclination towards art.

In high school I was assigned artwork for celebratory occasions. Thus, for the festivities marking the October 28th celebration (when Greece entered WWII) I’d copy the cartoons by Fokion Dimitriadis depicting Mussolini, which I drew on large sheets of paper using a marker, not pencil. This teacher invited me to his house and advised me to not only take university entrance exams but to also apply for admission to the School of Fine Arts. That was huge encouragement for me, which also triggered intense emotions as what he did was actually induce me to try for something beyond my imagination.

The rural setting I grew up in was defined by two mountains, Parnon and Taygetus. When we descended to another village to spend the winter, there were just the two mountains, Parnon to the north, Taygetus to the west, and nothing else beyond. The rest of Greece existed only in my imagination. I realised that my teacher’s inducement meant that I could go to Athens, study and become an artist.

Nude pose in the studio, 2001, oil on canvas

Nude pose in the studio, 2001, oil on canvas

It all seemed magnificent, but it was also a source of anxiety. At first, I was concerned over my family’s reaction, of how my mother would take it, if they’d agree or put obstacles in my way. To their credit, they placed none. At that time -I am talking about 1981- meaning 40 years ago, we did not stress over finding employment.

If you were not admitted to the university there was always agricultural work in the fields. In other words, questions such as “if I gain admission to university, how long will it take me to find work, what job will I find, what salary will I get?” simply did not exist. For better or worse, these anxieties were not there. Thus, I cannot claim that my family didn’t put any obstacle in my way just because they were so cool. They did not stop me because they did not have any other expectations of me, to be admitted for example to Law School or to study to become a teacher so as to have a stable job and salary.

Either way, my inclinations towards Humanities were visible. From the age of thirteen, I’d buy the weekly Epikaira magazine. It was a great news magazine that reproduced pieces from world magazines such as Time, Spiegel, Stern, Nouvel Observateur, L’Express, and Newsweek. It contained topics related to foreign affairs, domestic news, science, society, art and art criticism, it contained everything. Every Wednesday, the magazine was available in the small shop of my village and I’d wait with my five drachmas to buy it.

Woman standing in a pink room, 2007, oil on canvas

Woman standing in a pink room, 2007, oil on canvas

It was a way out for me, because I’d read Epikaira and there I’d find out about books of interest which I ordered from Sparta. Via this route, I acquired the History of Modern Painting, published by Ypodomi, the History of Modern Sculpture, the History of Music and the History of Theatre. Thus there was no way for me to be accepted by a prestigious faculty, because it was these books that I studied. I had learnt the History of Modern Painting by heart.

When I began taking lessons in order to take entrance exams for the Athens School of Fine Arts, I was not unprepared. I already had knowledge of the history of modern painting. Of course, I had no knowledge of old art because I had learnt about modern art first. That knowledge came after I gained entry to the School of Fine Arts and in time I became aware of the complexity of art.

Why did you choose representational art?

I will tell you what I think. I entered the Athens School of Fine Arts in 1982. If that had happened in 1970, I would probably be doing abstract painting. If I was eighteen in 1970, I would be conscious of the fact we had a dictatorship (1967-1974), I would be studying in a School that by its nature is distinguished by the quest for the original, the avant-guard, the innovative.

Girl in the mirror, 2009 – 2010, oil on canvas

Girl in the mirror, 2009 – 2010, oil on canvas

What’s more, the reason why abstract painting was the style in practice at the School in the seventies was not because it was adopted as a style with a delay of several years, but because of prevailing circumstances.

I believe that they practiced a defensive mode of art as if they did not want –probably unconsciously– to paint in a comprehensible and readable fashion in an environment where there was a dictatorship. It was as if they were telling censors that they could not comprehend anything about the art there.

In ’81 we were freer to express ourselves the way we wanted. Thus we studied and worked mostly with live models. We tried to paint what we were observing and we’d be corrected by our instructors. So the style and method was representational. We had a democracy, PASOK party had come to power gaining huge support from the Greek people and we knew and felt that in a democratic country we were free to paint whatever we wanted; that our work would not be censored, that I could paint what for example a girl holding a bouquet or a worker holding a trowel.

Ioanna, 2010 – 2011, oil on canvas

Ioanna, 2010 – 2011, oil on canvas

The painting style of my teacher at the studio, Panayiotis Tetsis, was representational, not realist. He painted the rocks of Hydra, the sea of Hydra, the street market. He was not one who would initiate his pupils, unawares, to the abstract format. After a while, as was his way with his pupils, we became friends, but we obviously treated him with due respect. I had the honour to be his friend to the end of his life in 2016. He played an important role in my artistic formation and he never stopped me from doing anything, on the contrary he encouraged me.

What is a painting to you?

It is the sincere revelation of one’s soul. At least this is what I try to feel when I enter a museum and see works which probably predate me by 300 or 400 years. Behind the web of codified shapes, colors, rhythms and contrasts in a painting that, for example, depict the Judgement of Paris or the Abduction of Europa, I try to understand the soul of the artist who created the work. If I were to give a more poetic response, I’d say that a painting for me is a prayer.

Nektaria, 2019, oil on canvas

Nektaria, 2019, oil on canvas

A favorite subject in your paintings is women. Why do you choose to paint mainly women?

I will answer in a way that is currently fashionable. I did not choose women as a subject, but merely followed my instincts. I already know that I want to paint the women of our time, who fleetingly pass me by. I also know that the only way to pass on to future generations an idea, mine at least, of what a woman of my time is like is to paint her.

This is my way of doing this. Another person may write a novel, while another perhaps a poem. I can see how different women are today from those, let’s say, of the generation of the Polytechnic School uprising in 1973. Painting is a silent art form, interested in affairs that perhaps other arts take no interest in; in the way women, for example, occupy public and private space, the way they move, cross or do not cross their arms, the way they cross their legs, not to mention the way they dress.

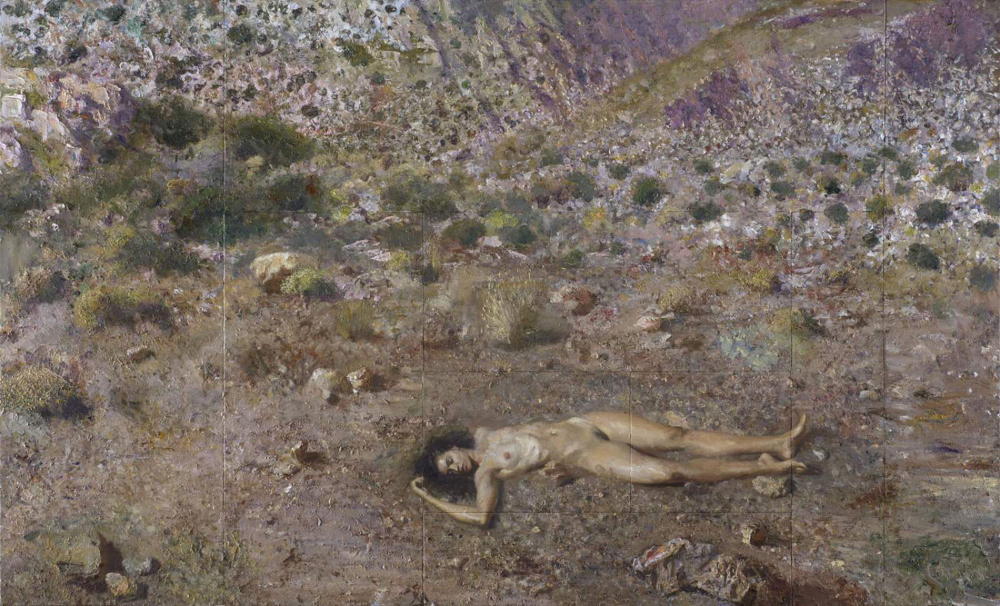

A rugged land, 2019, oil on canvas

A rugged land, 2019, oil on canvas

I believe that even the naked body has changed. When Georgios Iakovidis, for instance, painted a nude –Springtime– he had no concerns over how to paint the different skin tone of breasts and buttocks, since the model did not go sunbathing at the beach in summer. I, however, will paint it and it is a matter of concern as it is, in a sense, a record of time. I will also paint a navel piercing, because, rather than a pointless detail, it too depicts a point in time. When someone paints an electricity pole in a landscape, one understands that the landscape was shaped thus after electrification.

Moreover, women’s world and thus the condition féminine, woman’s nature, remains a mystery to me. The only way that painting can decodify mysteries is by depicting them; otherwise they remain elusive, mutating, constantly moving, and if not captured, nothing will remain and will finally be lost.

Yannis Moralis had painted some portraits of middle-class people in the 1950s. Whatever I may read, newspapers, financial statistics, advertisements or anything for that matter, I will not understand what a well-dressed woman looked like at the time. Moralis’ portraits faithfully depict the Greek middle-class in the 50’s. These alone are enough for one to understand what both men and women were like. This is what I want to leave behind for coming generations. My aim is that when two people stand in front of one my works in a hundred years’ time to be able to say: “This is what Greek women looked like back then”.

Mr. Rorris, are you preparing something for the future?

Yes, I am. The B&E Goulandris Foundation is doing me the honour of organizing for next summer a three-month exhibition of my works from 1982 to 2020, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Andros.

Portrait of Basil and Elise Goulandris, 2017 – 2018, oil on canvas

Portrait of Basil and Elise Goulandris, 2017 – 2018, oil on canvas

During all this time of continuous lockdowns for more than a year on account of the Covid19 pandemic, what was the source of your subjects?

During the first very strict lockdown of March-April 2020, when no one knew what this pandemic actually was or how dangerous it was, I did not go to my studio. I brought some materials home and I actually worked more than I do now; I had a good set of colored pencils that I rarely used, which proved excellent companions in difficult times.

Objects that had always been in front of me and which I bypassed, precisely because they were in front of me, objects that I had never thought of seeing as subjects of art, became my subjects; in other words, I painted a pepper, a piece of bread, a piece of cake, a pear, an iris, a glass of wine, a corkscrew. I did approximately twenty-five paintings.

At first, I made one a day. As time went on I became more demanding. And in the end, a painting of a packet of spaghetti took me eight days. The only problem was that within a month, I ran out of some colors and I waited impatiently for the shops to reopen to buy new ones. The lockdown ended on May 4 but I continued drawing these objects throughout May and I still had not finished. There are still many of those objects that I intend to paint and I hope to do so one day, especially a comb which I feel has been left out and may feel neglected.

Drawing of still life, 2020, colored pencil on paper (from the artist’s personal archive)

Drawing of still life, 2020, colored pencil on paper (from the artist’s personal archive)

Has the way you paint changed?

When I began to paint, I needed to set the scene, to tell the model what to wear and how to sit. I needed to embellish the world in order to paint it. Over the years, this tendency receded while I became increasingly skeptical over it, until I gave it up entirely. There is no need to beautify the world in order to paint it but to train the eye to see the ubiquitous beauty of reality.

Now I believe that if I am confined to my studio for ten years, I have things to paint for ten years. Besides, I have been painting in this room over the last twenty years and more or less the same subjects, usually a human being.

Drawing of still life, 2020, colored pencil on paper (from the artist’s personal archive)

Drawing of still life, 2020, colored pencil on paper (from the artist’s personal archive)

What changes in your opinion?

What changes? We live in a time when everyone asks what you paint while nobody asks how you paint. Depending on the question, you understand if the image is prioritised over the art of painting. Image and painting are two different things: The image is the result of painting and it differs depending on the form of painting. In this sense, the image does not change: I paint a human being.

Green Night (Portrait of E.S.), 2019 – 2020, oil on canvas

Green Night (Portrait of E.S.), 2019 – 2020, oil on canvas

The way I paint cannot be described in words because it concerns the diverse language of painting, which has its own grammar and syntax, it has to do with the warm and cool colors, the sharpness or bluntness of shapes, the dilution or density of colors, the intensity or moderation of rhythms, with the huge vocabulary of this language. The problem is that increasingly less people prioritise the art of painting over the image, which leads to confusion.

The intangible image of photography is confused with painting, which is a result of material elaboration. The shaping of form in paintings is not so different from the creation of man, according to the Book of Genesis. God created Adam from clay and breathed life into him. This is exactly what painting is. When the color in the palette becomes a stain, the painter needs to breathe life into it; every stain then connects to another, shaping the form which will be full of life, if the painter is good.

*Interview by Marianna Varvarrigou. Translation into English by Sofia Dimopoulou, edited by Magda Hatzopoulou. (Intro image: Marielena with Walkman, 1994, oil on canvas)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Discover the National Gallery of Athens; Painter Dimitris Tzamouranis: “Art’s ultimate objective is the pursuit of beauty”; Artist Stavros Kotsireas: “Creativity is part of our humanity”; Anna Grigora: “I only paint what makes me feel good”

TAGS: ARTS | GLOBAL GREEKS | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS