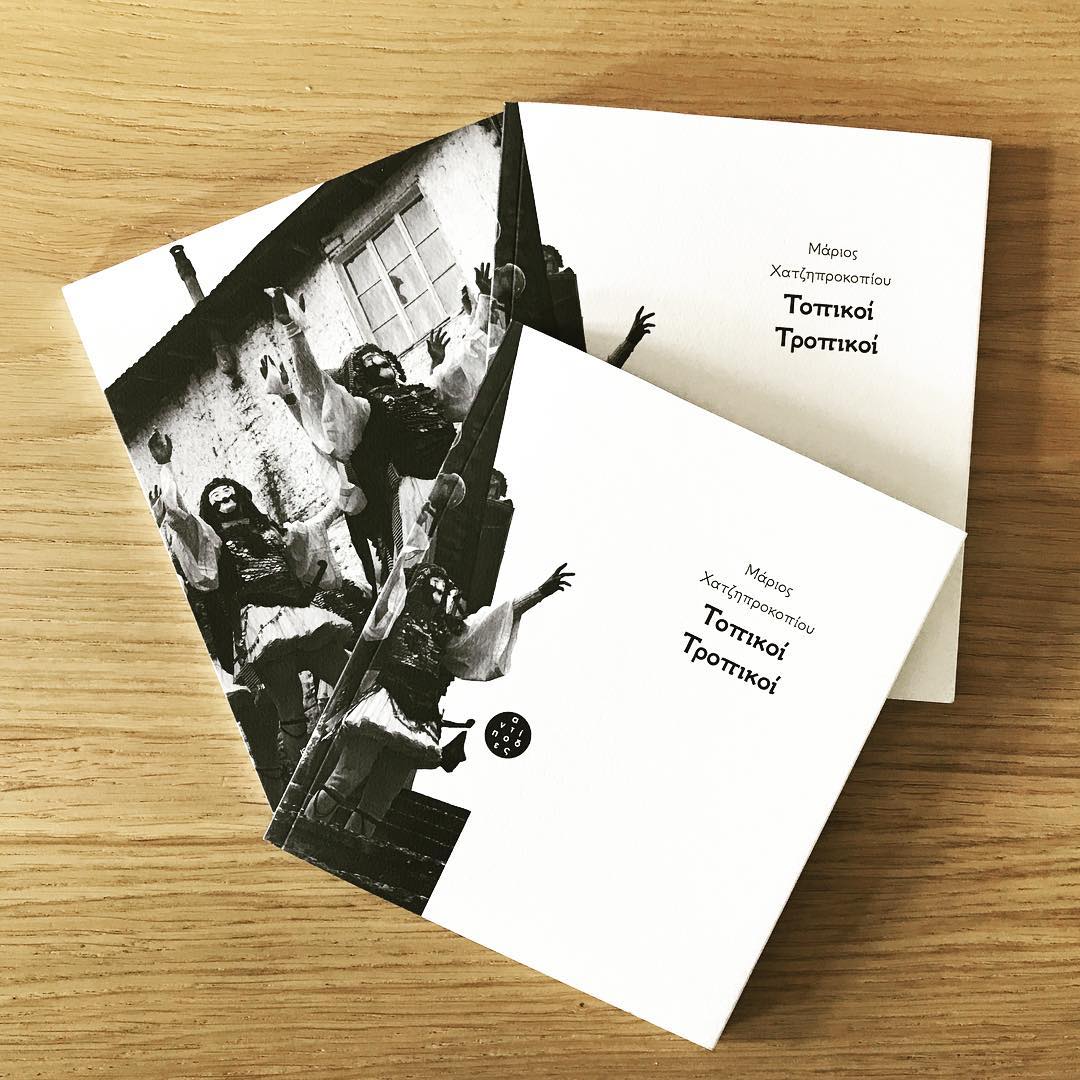

Marios Chatziprokopiou (b. 1981, Thessaloniki) has studied and worked in Spain, France, Brazil, and the UK. A poet-performer and performance studies scholar, he is currently living and working in Greece as a teaching fellow and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Thessaly. His first poetry book, Topical Tropics, is publishedfrom Antipodes Editions, Athens (2019). His poems have appeared in several reviews and edited volumes, and have been translated into English and French. He has presented his performance work in numerous cultural and academic institutions internationally. He translates Clarice Lispector from Portuguese to Modern Greek.

Marios Chatziprokopiou spoke to Reading Greece* about Topical Tropics, in which “demotic songs in a 15-syllable iambic verse and dirges in an eight-syllable verse co-exist with poems that deconstruct language, encapsulate foreign words and/or experiment with the sound of etymology”. He notes that he is interested in “the relation between poetry and performance, the connection of words to the voice and the body”, and adds that in this way poetry is transformed into “a collective experience in a shared time and place”. He also comments that “it’s urgent that poetry expands its vital space beyond the printed page […] to the extended text of the city”, and concludes that “resistance to a marketizing and marketable notion of ‘right now’, to which we are obliged to respond at a pace that is most of the time far beyond our control, may raise the issue of the political in poetry under reconsidered, and emancipated terms”.

Your first poetry collection Topical Tropics received rave reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

Within the framework of a fictional narrative – which resembles the structure of a theatrical play – there appear:

– Three characters: the father, the son, and the grandson.

– A heteronym: Dr. Nisefor Errantes.

– A – philological and at the same time family – “story”

In Athens 1914, scholar N.G. Politis publishes his “selections of songs of the Greek people”. Yet there is an unpublished manuscript comprising demotic songs that the father of modern Greek folk studies tries to hide. The manuscript is revealed by his renounced son, Alexandro Jorge de Carvalho de Polites. While kicked out of his family home, the prodigal son steals the manuscript. He starts travelling around the world, dispersing his prey, and at the same time writing verses in Greek. He finally settles in Brazil. In São Paolo of 2019, his son João Nikolao Polites da Silveira, a modern Greek studies scholar as his grandfather, undertakes a research project in order to safeguard the manuscript and make it known to the world. His partner Dr. Nikiforos Errantes undertakes the publication of thesilenced songs [father’s file], in counterpoint with the poems of Alexandro himself [son’s file], as well as a poem by Prof. da Silveira [grandson’s file]. The poems constitute the core of the book. They are framed by an introduction, comments and a glossary.

What was though the content of the manuscript’s songs and why, in our story, N.G. Politis so eagerly wanted to hide them? These texts refer to homosexual desire. They trace the multiple transformations of gender and sexuality, they celebrate the protean fluidity of eroticism, while lamenting and honoring all those who were considered unworthy of mourning. Similar quests cut across the free-verse poems that Alexandro wrote on the way. This is a book that puts together the voice of the father and the voice of the son, focusing on forbidden desire, gender as becoming, and mourning for ungrieved lives.

To use Yana Bukova’s words, “Topical Tropics is a poetry collection with literary mystification elements […] the most inspiring use of the demotic song’s technique I have ever encountered in a modern writer”. What role does language play in your writings?

I’m interested in a writing style that incorporates heterogeneous linguistic layers drawn from a wide time span; not necessarily monolingual. In Topical Tropics, demotic songs in a 15-syllable iambic verse and dirges in an eight-syllable verse co-exist with poems that deconstruct language, encapsulate foreign words and/or experiment with the sound of etymology. In fact, language and its boundaries constitute the very driving force of my endeavour: before I even invented the “Politis manuscript”, my attempt to write in a demotic song form came while translating the theatrical play Agreste, Malva Rosa, by the Brazilian author Newton Moreno (2004). There, during a traditional mourning ritual for a peasant, his female biological sex – unknown even to his female partner – is revealed. The mourning ritual is abruptly interrupted; mourners refuse to continue with their laments. Outraged, they ask the local religious and political authorities to intervene and they end up burning the house with the widow inside. In my search for a language that could transfer the idiomatic elements of the Portuguese source text in Greek, I repeatedly failed in all my attempts for a “faithful” translation. Consequently, I resorted to the poetic form of demotic songs, and ended up freely adapting the Brazilian play in order to create a totally new text.

“What I translate, translates me as well”, writes Alexandro, the prodigal son, in his travel notes: this initial presence of a demotic song in my writing impelled me to compose more, always inspired by secondary texts and/or more extended narratives. I thus gradually composed an archive of queer laments: dissonant, translingual, intertextual; sexually, but also culturally queer. Practicing with both familiar and restrictive rhythms and poetic meters offered me an opportunity to move beyond my personal feelings and experiences, a liberating chance to move away from myself. It was also a chance to channel my personal pursuits – infiltrated by the present – towards traditional modalities and rhythms. The modality of demotic poetry has always interested me for the additional reason that these songs manage to condense whole stories, complete dramas, in so few words. Their dense, verb-driven narrative finally influenced my free-verse poems as well.

Working on the poetic tradition, the bet was to disconnect it from the various formal discourses which were at times articulated in its name (folklore, school textbooks etc) and to make it familiar anew, paying tribute through its sounds, images and symbols, to the nation’s outcasts: all those excluded from dominant national narratives, those whose desires and losses have always been considered delinquent; and thus punished. To honour all those excluded from official memory. This writing venture has started out of a two-fold need: to apprentice into folk poetry and at the same time incorporate in this special language experiences that might at first hearing sound unfamiliar. Through this familiar language -especially for the older generations-, I also wanted to bring forward desires and losses which would in any other language sound unacceptable and unheard of. My writing in this case is ruled by a need for reconciliation, a demand for forgiveness (in the Greek sense of making place for). And it is crucial that those who can now forgive are the unappreciated ones.

Your poetry and the performance of your works constitute a successful example of experimentation away from conventional forms. Could this combination of dramaturgy and narrative be a way to bridge the gap between the writer and the reader?

All in all, I am interested in the relation between poetry and performance, the connection of words to the voice and the body, the poem as an oral and thus live experience. I reckon that it is important to keep in mind that the thread of orality unfolds in an extensive poetry spectrum: from bards and troubadours to the experimentations with sound, voice, and corporeality in the 20th and 21st centuries. I wouldn’t so much talk about a combination of dramaturgy and narrative but rather about a connection between narrative and performance. Dramaturgy permeates the two so as to create narrative fragments in a live event. Such a gesture indeed brings poetry closer to its audience, transforming it into a collective experience, in a shared time and place. And I feel there is an increasing vital need not only to hear a story – through the language of poetry! – but to hear it through the bodies and voices of poets.

In the last few years such initiatives are becoming more and more frequent in Greece as well, a country where, still, poetry is often considered a ‘noble’ genre, not to be performed in ways other than the conventional recitation or a silent reading. In this respect, I would like just to mention, and in no way aspiring to a thorough review, a number of such collective moments of poetic performance (without touching upon the work of individual poets): karaoke poetry bar (back in 2007!) by intothepill team, an initiative of Katerina Iliopoulou and Yiannis Isidorou; the 1st prostíbulo poético (2011) again by a team which was later to publish the [frmk] journal, as well as the 2nd prostíbulo poético, co-organized in the occupied theatre Embros in February 2013; the polyphonic reading of TETTIX by Phoebe Giannisi at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (2012); several events of [frmk] such as, for instance, “The Six Paths: a night of literary divination” (2016); the poetry and performance relay race Exulat curated by Vassilis Amanatidis at the Dimitria Festival (2015); the literary performance festival which took place in the Monokeros Hall during the International Book Fair (2018-19) organized by Pavlina Marvin; Poetry on Stage: Multimedia poetry performances by Greek poets at the University of Brighton organized by Patricia Kolaiti; several slam poetry nights organized by the publishing initiative queer ink; the international festival Sardam, organized since 2013 in Cyprus by Maria Ioannou.

While participating in Sardam three years ago, I had the chance to meet the Hungarian poet and performer Katalin Ladik. I think of her because the organic continuum among the word, the voice, and the body in her work defines the way I understand performance poetry. In my view, it’s not about a “dramatization” of language on theatrical terms, neither about ‘framing’ poetic recitation by visual acts. It’s not about an alleged lack of poetry that, in order to bridge the gap with the reader, is supplemented by other means. It’s not an additive process. Rather, it’s about words themselves as a starting point and as the core, about their sound moving towards certain modalities of voice, about the voice making the body vibrate. Or, to use the words of my beloved Federico Garcia Lorca at a lecture about Granada during which he played the piano and sang: “yo no canto como cantante sino como poeta” (“I don’t sing as a singer but as a poet”).

Modern Greek poets have quite different attitudes toward the Greek visual arts and to music. How is this overwhelmingly visual conception of the world that Greek poets have to be explained?

Although I appreciate this analysis for its historic overview which goes way back, I am not sure as to whether it accurately reflects the present. Most contemporary Greek poets, as V.L. himself has correctly pointed out elsewhere, are not restricted to just one artistic field, but are rather moving between different arts and means. They are in between mediums – the same way as everyday communication, especially the distant and online communication we are called to live with during the current pandemic. They are influenced from, or already incorporate in their work sounds, voices, moving or fixed images which are continuously recorded by the most user and pocket friendly means, and they mediate the present. If I could think of a respective preference of poets for visual arts on the expense of music today or maybe a more open communication between the two fields, I would rather put it down to the expanded field of contemporary art itself, and its openness to a broader spectrum of means, including the text, the voice and the body.

You have translated The Passion According to G.H., The Hour of the Star, and the Family Ties, by Clarice Lispector (Antipodes Books). Which were the main challenges while translating this major Brazilian writer?

«The unsayable can only be given to me through the failure of my language”, says Lispector, through the words of G.H.; and to translate her novels poses challenges and opens room for failure, as with a philosophical text or an extensive poetic work. L. uses a language of her own, “strange even in her native language”, deconstructing both syntax and grammar rules. She disrupts, to an extent often unthinkable for translators and editors, the obvious punctuation in order to serve her own rhythms. “With only one way to punctuate, I juggle with intonation”, says, through the words of the hero-writer, in The Hour of the Star. Thus my main concern was to try to safeguard the ruptures and freedoms of her language, not to smooth her idiosyncratic writing into “normal” Greek. I had to invent a new and strange language in my own mother tongue, to test its limitations, and to expand it.

“Words”, says the writer/Lispector in The Hour of the Star, are “sounds transfused with unequal shadows that intersect, stalactites, lace, transfigured organ music”. Translation is in its turn a score reading, a transfusion of music. Herein lies the pivotal importance of reading the text aloud while translating it, over and over again, in an attempt to transfer not just the meaning but the rhythm of the original. After all Lispector herself referred to the importance of “an exhausting loud reading” for her own work as a translator, while she considered that “every writer is born an actor”. And she manages, despite her recognizable writing style, to change her linguistic costume in each of her books, forming quite different idioms: different costumes, which the translator is called to invent, and be dressed, in his/her turn.

L. constitutes a voice so strong that you sometimes get the impression it inundates you, that it leaves indelible marks on your body. Her sound accompanies you like a second breath – which can be dangerous, especially if you are a writer yourself. This is the greatest challenge, and at the same time the biggest opportunity: to be in dialogue with someone who isn’t afraid of failing; and who, through the failure of her language, is offered the unsayable.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How would you comment on this strong civic awareness?

It’s urgent that poetry expand its vital space beyond the printed page: to the voices and bodies of poets and/or readers, to the time and place of a collective event but also, as a writing genre, to the various forms you mentioned, to the extended text of the city. My only reservation has to do with the use and transmission of poetic fragments by powerful cultural institutions, as has sometimes been the case in Greece during the last few years: I am afraid about whether such gestures “from the above” may annul the political and aesthetic sharpness of poetry, usually acting as an advertising spot.

Your remark raises at the same time the crucial and urgent issue of the broad appeal of poetry and poets. In the previous decade, we witnessed not only a plethora of new poetic voices but also an unprecedented public interest in these voices, usually in correlation to the political and financial vicissitudes the country was undergoing. Yet, I remain skeptical: during the so called “crisis”, poetry’s inherent political weight, which is intrinsically linked to its aesthetics, was not always emphasized in the public sphere. Instead, poetry was rather used to directly capture and/or reflect the political. I understand the underlying strategies behind such an approach. I am fully aware though of the risk, especially when one addresses a foreign audience, of being defined by the expectations of the others, and in this move exoticizing one’s self: a process which ends up falling within the transactional cycle of offer and demand.

In the aftermath of a decade of “crisis”, and with the international interest for Greece and its poets somewhat dwindling, but also on the threshold of a new, much more unprecedented and unpredictable, global crisis triggered by the current pandemic, I can’t help but wonder: how can a poet’s political vigilance be articulated without “faithfully” responding to “external” expectations? How can someone, writing within the contemporary framework of a world in a concurrent “live broadcast”, resist its persistent urge for an easily recognizable and consumable product? Resistance to a marketizing and marketable notion of “right now”, to which we are obliged to respond at a pace that is most of the time far beyond our control, may raise the issue of the political in poetry under reconsidered, and emancipated terms.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Panayotis Ioannidis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE