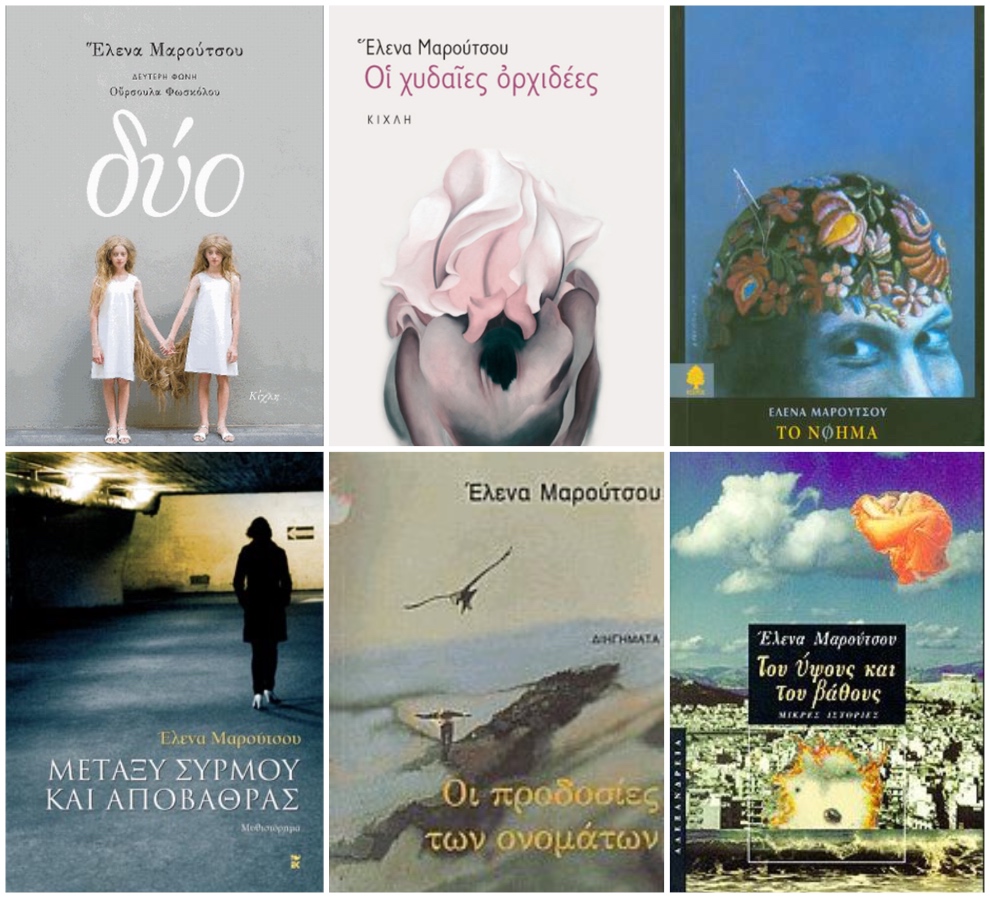

Elena Maroutsou was born in Athens in 1967. She studied History at the School of Philosophy (University of Athens) and pursed postgraduate studies in Literature and the Visual Arts at the University of Reading, UK. She teaches Modern Greek Literature and Creative Writing, while her book reviews appear regularly in the Greek press. She has published the following books: Toυ ύψους και του βάθους (High and Low, Αlexandria, 1998), Οι προδοσίες των ονομάτων (The betrayals of names, Αlexandria, 2004), Μεταξύ συρμού και αποβάθρας (Between the train and the platform, Κastaniotis, 2008), which received the Athens Prize for Literature Award for Best Novel in 2009, Tο νόημα (Τhe meaning, Kedros, 2010), Οι χυδαίες ορχιδέες (Indelicate Orchids, Kichli, 2015), shortlisted for the ‘Anagnostis’ Award, the National Literary Award for Best Short Story and the Academy of Athens Award), Δύο (Two, Kichli, 2018 shortlisted for the National Literary Award for Best Novel) and Θηριόμορφοι [Beast-like, Polis, 2020).

Elena Maroutsou spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest writing venture Beast-like, which is based on the idea that “even the most sophisticated, mild-mannered and civilized person hides a ‘beast’ within, which under specific circumstances may be brought to the surface“, and comments on her inclination “towards experimentation with form” given that “intertextuality always finds a way through almost all [her] books in the form of conversation with other texts or works of art“.

Asked about the relation of literature to the world it inhabits, she notes that although “reality constitutes the primary mold“, “the moment a work of art is born, it acquires its own autonomy“, while, as for the potential of Greek writers to move beyond national borders, she concludes that “a literature of high quality and great diversity is produced in Greece nowadays, that foreign readers would be more than willing to discover“.

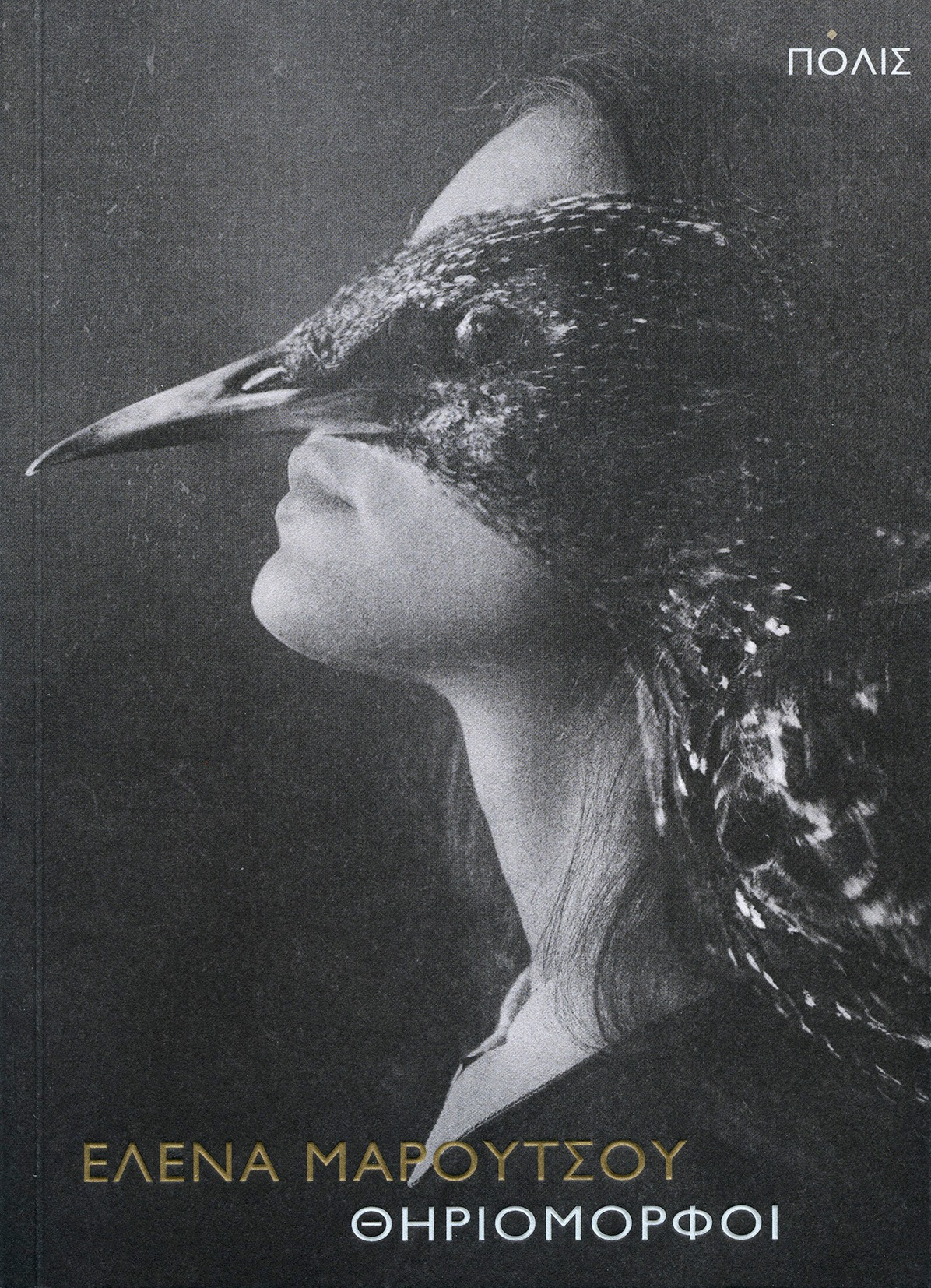

Your latest writing venture Θηριόμορφοι (Beast-like, Polis, 2020) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The novel is based on the following idea: even the most sophisticated, mild-mannered and civilized person hides a “beast” within, which under specific circumstances may be brought to the surface. These ‘bestialities’ appear throughout the plot at various levels: love, family, education, religion, history. After all, since part of the narrated events take place in Krakow, there is a scene unfolding in Auschwitz, a camp-symbol where one of the major contemporary historical atrocities took place.

You have characterized the co-existence of text and image as a form of conversation, a kind of polyphonic song. Could you elaborate on this interesting experimentation away from conventional forms? In this respect, what purpose does language serve?

While I have for long been interested in the issue of boundaries between man and animal, what triggered the writing of the book was my acquaintance with the work of Polish photographer Laura Macabresku. Her photos dictated the atmosphere of the novel and inspired numerous elements of its plot. After all, it’s not the first time that one of my books relies on the synergy of text and image. In Between the train and the platform (Kastaniotis, 2008), which received the Athens Prize for Literature Award, there were integrated 45 works of Rene Magritte, while in Two (Kichli, 2018) there is reference to the photos of Diane Arbus, sketched by painter Evi Tsaknia.

The language of visual arts is both familiar and attractive to me due to my short creative engagement with the art of photography and my post-graduate studies (Literature and the Visual Arts, University of Reading). It may as well stem from the way I think and express myself through metaphors and thus the connection of speech and image comes naturally as a conversation between the various instruments of an orchestra, which perform the same melody.

Since your first book in 1998 what has changed and what has remained the same in your writing? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your books?

What remains the same – if I am allowed to comment on my own writing – is my inclination towards experimentation with form, the playful element in combination with that of drama, as well as a reflective mood and a care for language. Intertextuality always finds a way through almost all my books in the form of conversation with other texts or works of art. I am particularly interested in the role of art as a reflection of reality. In my latest novels, one could observe an attempt to interweave personal with collective experience, not so much in the form of a traditional social novel but in the way this is achieved by myths, mostly through the use of symbolic elements.

What is the relation of literature to the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to describe what could potentially be radically different realities?

The way literature relates to reality is far from one-dimensional. I do not share the opinion that art is a product of social structures. Of course reality constitutes the primary mold: writers have not come out of nowhere; they were born within a concrete historical and social conjuncture, which has left its imprint on their work in more or less conscious ways the same way a family tree leaves its imprint on a person’s traits. Yet, the moment a work of art is born, it acquires its own autonomy, initiating a dialogue both with the past and the present and thus helping form through its expressive means a new, parallel reality, which may reflect, comment, turn its back on or deride the current reality, play with it like a child, dynamiting it like a revolutionist or fertilize it like a lover.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

Greece has a long and rich tradition in short stories while in recent years there are indeed published short story collections with shorter and shorter stories given that contemporary writers tend to experiment with short form in its most concise form, such as micro fiction and bonsai story telling. I am in no position to analyze the phenomenon apart from the obvious observation that the internet and social media have fostered this concise means of expression and have created a type of ‘touring’ reading, which has minimized the time of concentration on a text. Yet, the majority of readers (and thus publishers) continue to opt for novels, which achieve higher sales. Personally, as a reader I enjoy both the long and short form, while as a writer I have experimented with both.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure activity and thus earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

Indeed, in Greece there is only a small minority of writers who manage to earn a living through their books. Thus, writing becomes a ‘side employment’, with little or no profit at all while at times it burdens the writers since there are publishers who ask the writer to contribute financially to the publication either in part or entirely. This phenomenon has partly been triggered by certain objective difficulties, such as the small book market in Greece. Moreover, the economic crisis of the last decade has further limited the purchasing power of readers, with several publishing houses and bookstores going bankrupt, while others just strive to survive, usually sacrificing the percentage on profits a writer is entitled to.

I am not sure that the situation could be reversed; yet specific state planning and policy is required. A primary goal should be to strengthen love of reading in education, establish more public libraries, promote the Greek book abroad, allocate money for the translation of Greek titles, create a social security institution for writers and translators etc.

The new generation of Greek writers has been characterized as multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. How do they relate to world literature? How does the local/national interweave with the global?And, in turn, do Greek writers have the potential to move beyond national borders and attract foreign audiences?

It’s true that the majority of contemporary Greek writers belong to a generation that has learned foreign languages, studied or pursued post-graduated degrees abroad, travelled, gained access to the internet and thus their identity has been forged by a multicultural aura. The quest for a national identity is no longer a major issue; neither is the aspiration to belong to a literary ‘generation’ with common traits and goals given that contemporary writers form a diverse mosaic both in terms of content and form. As for the potential of Greek books to move beyond national borders, it depends not only on the plan and policy that is implemented within the country but also on the interests and openness of foreign markets. I reckon that a literature of high quality and great diversity is produced in Greece nowadays that I am sure foreign readers would be more than willing to discover.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE