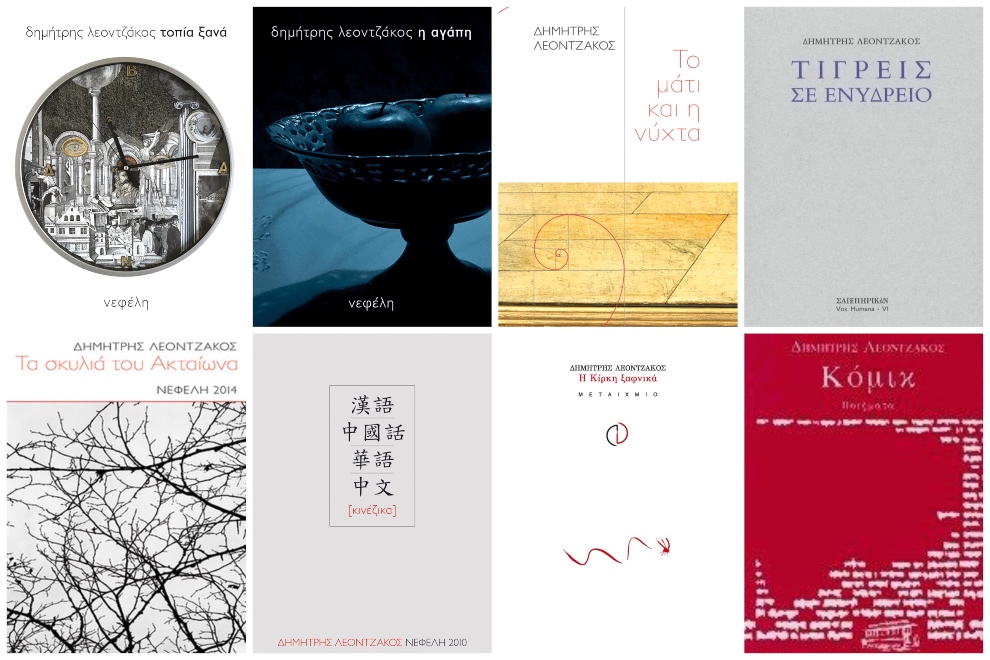

Dimitris Leontzakos was born in Kavala in 1974 and lives in Thessaloniki. He studied music in Thessaloniki, Munich, Rome and New York. He works as a musician. He has published seven books of poetry: Comic (Ta tramakia Publications, 2001), Circe, out of the blue (Metaixmio, 2004), Chinese (Nefeli, 2010), Aktaeon’s dogs (Nefeli, 2014), Tigers in aquarium (Saixpirion, 2016), The eye and the night (Nefeli, 2016), Landscapes again. Love (Nefeli, 2018). His poems have appeared in many literary journals, e-journals and anthologies both in Greece and abroad.

Dimitris Leontzakos spoke to Reading Greece* about the way his poetry evolved through the years, noting that although there are cycles of his books that “reveal, move around or delve into the same language or theme”, it happens that “the material leaves aside the old ways and opens up to other fields, deviating towards the other”. He comments that “a major issue in poetry is touch”, with poetry as “the skin of an impossible world on us”, he explains that “the moment of writing, that trice of creation, is, for [him] a kind of mystery than a treatise”, and adds that “the world is elusive, and, by writing, we make it even more real. By speaking we eliminate the light. By writing we enhance the dark”.

Seven poetry collections within a period of almost ten years. How has your poetry evolved through the years?

My first book was published in 2001 by Ta tramakia, a publishing house in Thessaloniki and was titled Comic.

Since then I have published six more books – that is seven in total – but actually eight poetry collections, given that my latest book titled Landscapes again/Love, published by Nefeli in 2018, comprises two collections of prose poems. Two books that stand autonomously, and yet are related, reverse and at the same time consistent with that same impossible deflection, popular orientation or imperative: towards the stars. Furthermore, three more extensive books of poetry are ready and will be published in the following months. It’s in this capacity that I address you.

I guess there are cycles or groups of my books that reveal, move around or delve into the same language or theme. Then – always elusive as to what happens or why it happens, what precedes and what comes next – the material leaves aside the old ways and opens up to other fields, deviating towards the other. In this respect, I would say that Chinese, Aktaeon’s dogs and The eye and the night share the same style and language. Although they are three distinct books written with completely different linguistic tools, they have something in common, which is articulated timidly, unfolds and evolves and in the end erupts deafeningly leading to what comes next. Landscapes and Love explore something else. I feel in some short of metaphysical way that they constitute the equator of my poetry. I don’t really know what that actually means. That’s why they were published together.

Aria – still unpublished – is a pivotal book in my poetic course. Ishouldstopatthispoint. Let me remain silent as to my next poetic works.

In his review of your poems, Vassilis Amanatidis notes “enigmatic poems, but not at all utilitarian, crystal clear, but not plain, as well as – I believe- in tune with our dry, but not desiccated present, therefore poems that are contemporary”. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

Mute language, vertical writing, timeless myths and the speaking existence, just to mention a few.

I reckon, however, that a major issue in poetry is touch. Poetry constitutes the skin of an impossible world on us. I strongly believe that. I may not always mention or articulate it or even think about it, yet this is the whole issue, at least the way I feel it. Our failure to remain close to that moment is called poetry. Let’s take Cavafy or Solomos for instance.

I would say that style – this elusive something – offers a poem the imperceptible puzzle of its vocalization, the thrill of its writing. The closeness and the dizziness of an unknown world next to and outside it. Yes, I am an enigma that never ceases to not be written and I like the condensation. The play, the timeless colors, the sharp falls. Since an early age I have been wondering whether we can have in language, in poetry, what we call chord in music. This is my impossible disability. Persistent, acoustic, existential and inconsolable. Almost like a childlike desire.

There are so many things that connect me to Vassilis. Like two strings attached – nailed – to the same spot. And as they vibrate, they deviate. And while deviating, they make sound. Yes, we make sound; though not in the same way but under the same touch, under the same darkness.

And with the same bow let me add. Which in life, as well as in poetry, is this flee called silence, lucidity or merciless time.

Ιn your poetry you seem to experiment both with form and language. Would you characterize this experimentation as a way to disorientate and at the same time re-establish reality through art?

I don’t consider myself experimental either by nature or by intention; I would say I am rather silent and inhibited and most of the times I get easily bored. I am a shy person with foolish outbreaks of courage, mostly verbal. Yet, this is something I appreciate. My stance towards writing is a stance of bewilderment. It’s a mystery one has so many things to talk about. I myself have tried it. After all, I love theory, philosophy, psychoanalysis and all the rest. But the moment of writing, that trice of creation, is, for me, more a kind of mystery than a treatise. My trust lies not with eloquence, but with spasm, with hiccup- like Aristophanes’ hiccups in Plato’s Symposium – with failure. After all one has to support that things fly unknowingly and indefinitely high in the air. And they fall. That fortune is the last goddess of poetry. And the meeting is the extreme raft of a, let’s say, hopeless, oral reality.

Up to this point I consider myself truly lucky. I have been utterly destroyed in innumerable poems. I have come across what I don’t usually write; which apart from a bit funny, it’s also kind of tragic. At the end of the road I find what cannot be written. At an existential level I feel more and more mundane – yet not desperate.

The road and the real could be a potential answer to your question. Given that as a poet I am totally indifferent towards reality; yet the opposite goes for painting. For me the real looks like color. At some point, in a kind of revelation, I realized that you can find nothing on the road. And at first I thought this was bad. Indeed. Poems do not frequent there. Yet where do they frequent? Today I would say something only slightly different. A bit shifted. Imperceptibly, unwittingly or slightly different.

You can find nothing real on the road. This nothing is the poem. After all the real could be identified as the one that is missing. Thus poetry is missing. We are interested in this nothing. Let’s, thus go light-heartedly, through speech, for a walk amid the wild night of the poem.

Ποίημα είναι η επινόηση μιας ανείπωτης αυγής στην ανύποπτη χλόη πάντα μιας νύχτας.

[A poem is the invention of an unspoken dawn in the unknowing grass of always a night]

Vassilis Lambropoulos has argued that Greek poets have always had an overwhelmingly visual conception of the world, adding that “this phenomenon has been changing dramatically with the new poetry, because many of its writers are excellent musicians too and many others have impressive musical sophistication”. Is it possible, after all, for poetry and music to converse? Or else, where does the musician meet the poet in your work?

As I already mentioned, I consider Aria a pivotal book in my poetic course. First of all, because I was startled to realize that it started to unfold around an entirely musical idea and an existing musical work. Things I try to avoid. That is, the Aria from Goldberg Variations by J.S. Bach. Music was finally brought to light and its relation to my language was delineated. Or else, the borderline between letters, light, color and sound. That is the wall of the real.

In addition, in the book – which I hope will be published soon – I tried to articulate a question: to which extent can a poem be shortened, be minimized? Not how long or how short a poem can be. But rather how minimal. Short and minimal are two entirely different things. And there lies a crucial question for art. I don’t know if I can explain myself but for me this is a highly important issue.

This spectacular prison we are nowadays obliged to live in can only broken free through such minimal, imperceptible blind spots. A work of art as a rupture. The image has become suffocating in an unpleasant, unbearable, even totalitarian way. Just to offer some insight as to what I have in mind, let me mention the musical miniatures of Anton Webern, the color dots of Paul Klee or the fireflies (lucciole) of Pier Paolo Pasolini, as they are still glittering in the dark of the 26th canto in Dante’s Inferno.

The world will become an image, in the prophetic words of Giorgos Chimonas. The world is elusive, and by writing, we make it even more real. By speaking we eliminate the light. By writing we enhance the dark.

You have characterized poetry as “that impossible way out of a continuous crisis, in the sense of discontinuous lack or discontinuous poetry”. How does poetry relate to the world it inhabits?

Indeed, I reckon that poetry should remain focused on the impossible; that is, nailed and spoken as a tree. Not visual. In the extravaganza that prevails nowadays, poetry should try to remember, to close its eyes. To set sail anew. Speaking, flying, lacking and void.

Within the same framework, I would say we should let things free, to raise them up on the air. Poetry should nowadays become groundless anew. This is its small, minimal revolution.

After all, it’s lack that constitutes poetry’s essence. The simple air. This is where a great opportunity for poetry lies nowadays. These have always been its materials. And at times nothing is a material too. Let’s not forget that. And this nothing acquires its primitive dimension again through the poem. A dimension or existence it has always had. Like in the dream. In the dream, not in dreams. Because poetry should not be concerned with happiness, the same way reality isn’t. Poetry doesn’t make us happy. If poetry creates a space, it’s not a space of happiness, nor of unhappiness in this respect. Poetry is an area of desire. Or even better an area of deviance; that is a small, minimum distortion. Where this lack becomes what has always been, namely language. And a white bone out of the invisible; that is, something. Something real.

It creates the poem out of nothing, that is from words, a hole in the world. And this is indeed important. Think of the gates in the walls of the unbearable defeat which shines at the beginning of poetry and is called Troy. It still flaps interminably. Think of the Seven against Thebes.

How would you comment on current literary, and more specifically poetic, production in Greece?

Interesting, multi-thematic, unexpected, thriving. Thatisunknown.

Note that this nothing constitutes the prerequisite of every creation.

Let me conclude with some verses from the unit Every angel is awful/ Sixteen points on poetry and the crisis. Verses written, through an erratic lens, in a positive way so as to provide strength even in the most difficult times. I cite them as a kind of wish for all of us.

10.

Στη ρωγμή της απόλυτης φρίκης, της καταστροφής και της έλλειψης ανθίζει το ποίημα. […]

[It’s in the crack of the absolute horror, total destruction and lack that a poem flourishes. […]

6.

Ποίηση είναι η εμπειρία του ακόμα χειρότερου.

[Poetry is the experience of the even worse.]

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE