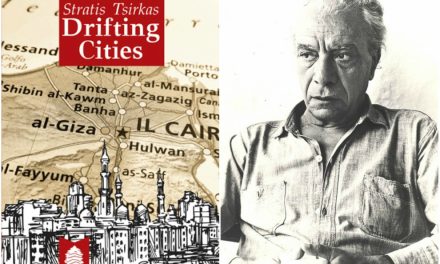

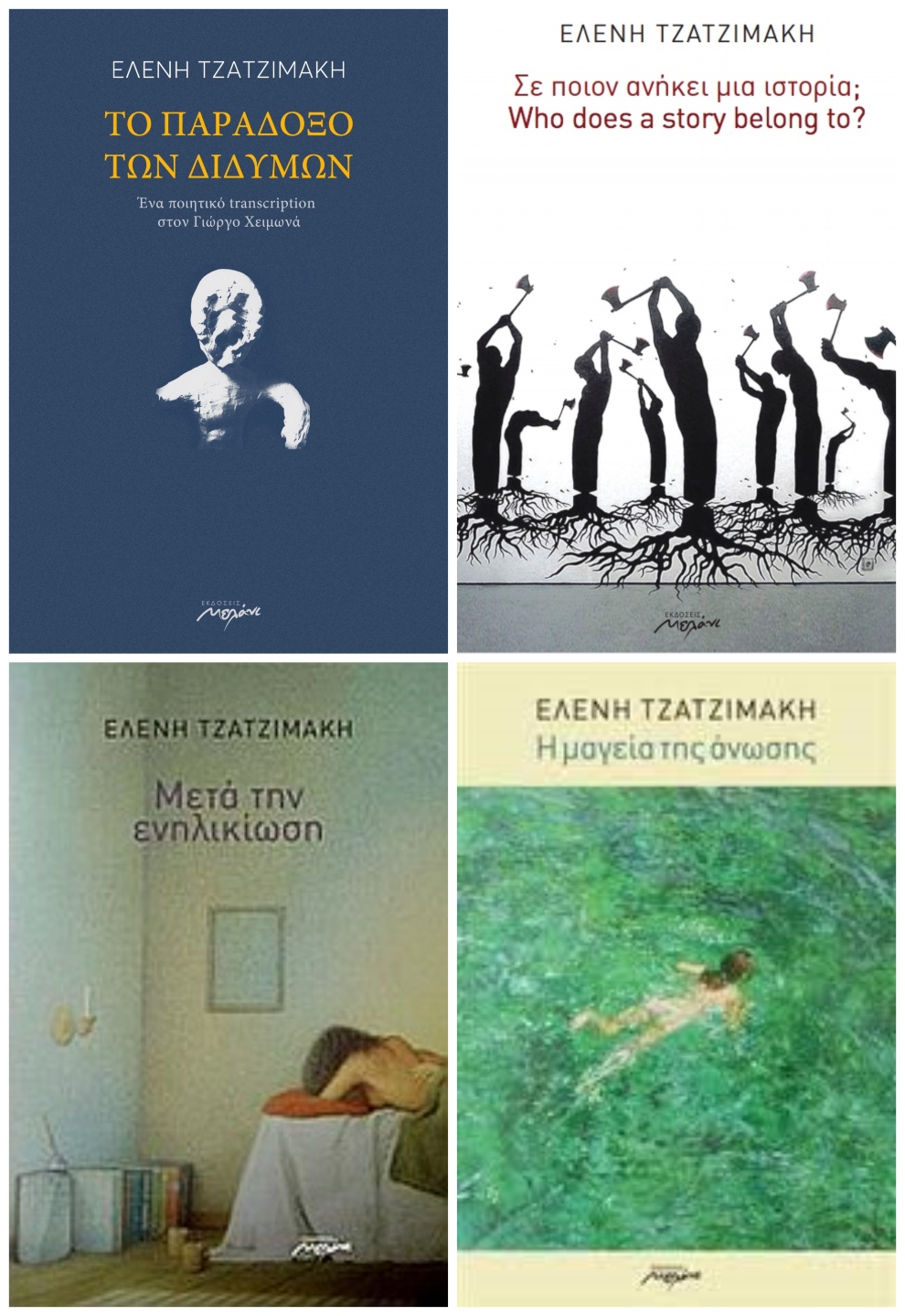

Helene Tzatzimaki was born in Athens in 1986. She is a PhD candidate at the Department of Modern Greek Literature. She has published four poetry collections, all by Melani Editions: The magic of upthrust (2009), After adulthood (2012), Who does a story belong to? (Bilingual edition, translated by David Connolly, 2015) και Twin Paradox-a poetic transcription to Yiorgos Cheimonas (2018). Her poems have been translated into English, French, Italian, Slovenian and Romanian. She has translated modern Palestinian poets (in cooperation with Ismat Sabri), as well as modern European fiction. She is also a professional musician (modern and jazz vocalist).

Helene Tzatzimaki spoke to Reading Greece* about the way her poetry evolved from one book to another, noting that among the main themes her poetry touches upon is “a systematic return to the issues of memory, dream and revolution”. As for language, she commented that as years go by, she years “for the simplicity and frugality of verse, where meaning is powerful in itself”, while she also explained that “poetry meets music at the pivotal point of rhythm, which is a prerequisite in both”. “With the primordial immediacy of both speech and sound, they cast their spell on their recipient before they become products of his logic, and this is what makes them such powerful arts”.

You have published four poetry collections within a period of ten years. How has your poetry evolved from one book to the next? Which are the main themes your poetry touch upon?

It’s not so easy for me to define the changes that occurred from one book to the next, given that it would require taking a safe distance from myself. What I can say for sure is that each book refers to a specific period of my personal life, which is indeed reflected in my poems both in terms of subject and style. At a second thought I could say that through the years my poems stopped being self-referential and confessional. I no longer felt that need: poems ought to be useful to the reader, and not just a chance to look through the keyhole. As for the themes I am most interested in, apart from a recurring reference to the issues of love and death, I notice a systematic return to the issues of memory, dream and revolution.

Kostas Papageorgiou has commented on the way you use language as a malleable material for the poetically drastic depiction of volatile thoughts and emotions, consolidating this volatility. What role does language play in your writings?

As far as I am concerned, language constitutes a vehicle and not an end in itself. I reckon that the poem, as an experience, a testimony and an artistic construction, has been shaped long before it is put into words. This in no way refutes the predominance of language and the way one treats language poetically. As years go by, I appreciate and yearn for the simplicity and frugality of verse, where meaning is powerful in itself.

Your poems are permeated by a strong lyricism, bearing at the same time the traits of the present era. How does your poetry relate to the world it inhabits?

Every creative act, including the writing of poetry, is also a product of our existence as social beings. It not quite easy to honestly be our true self towards the poem. We are a product of our era, which, whether we want it or not, permeates us not always in a positive way. I don’t really know whether my poetry is reflective or the world or the era we were born in. Yet, as a person, I am very interested in what happens around me both at an individual and social level, as well as in terms of their political, social and cultural transformations.

“Revolt constitutes an open scheme, as well as an urgent demand. Yet it should first turn against its own self, that is against the crudeness it defines itself amid the ideological pulp of our days”. Tell us more.

Revolt, as a concept, constitutes or should constitute a constant demand and tool for our societies given that it is the only way to bring forward their negative aspects – which have always existed and will continue to exist. Yet, for a revolt to bear fruit and thus become an early manifestation of a revolutionary process, it should be not just a revolt of affect but rather arise from a deep knowledge and understanding of the essence of things. You cannot change a society if you have not rejected it in all its aspects; yet you should be aware of these aspects in terms of individual and collective responsibility. Every social noise is necessary; yet for noise to become music, it requires knowledge, awareness, work and subversion. I am against a superficial approach of things.

“Poetry and music constitute different aspects of the same need: the need to express my self”. Where does the poet meet the singer in your work?

At a technical level, I reckon that poetry meets music at the pivotal point of rhythm, which is a prerequisite in both, whether poetry is in verse or free. Rhythm constitutes the deep internal vibration of the text, even of a prose text. It is the balance, an irrefutable proof of a good writer who knows how to control his words, what he wants to say and how he says it. Personally speaking, I have always felt and still feel I need both music and poetry as my unique ways to share things that I could in no other way express.

Nikolas Evantinos has characterized poetry as the deepest music of language. Is it possible, after all, for poetry and music to converse? What is it that binds them together?

Music invades the space in the same way as a verse, which, although you may not be fully aware of its meaning, demands a part of your senses. Imagine how many times we were moved by a phrase or melody, without being able to define the reason why we felt this way. I consider that poetry and music are related in that they operate at an emotional level before you are able to logically process and evaluate them and this is their great mystery. With the primordial immediacy of both speech and sound, they cast their spell on their recipient before they become products of his logic, and this is what makes them such powerful arts.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE