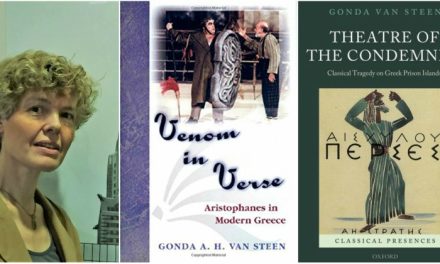

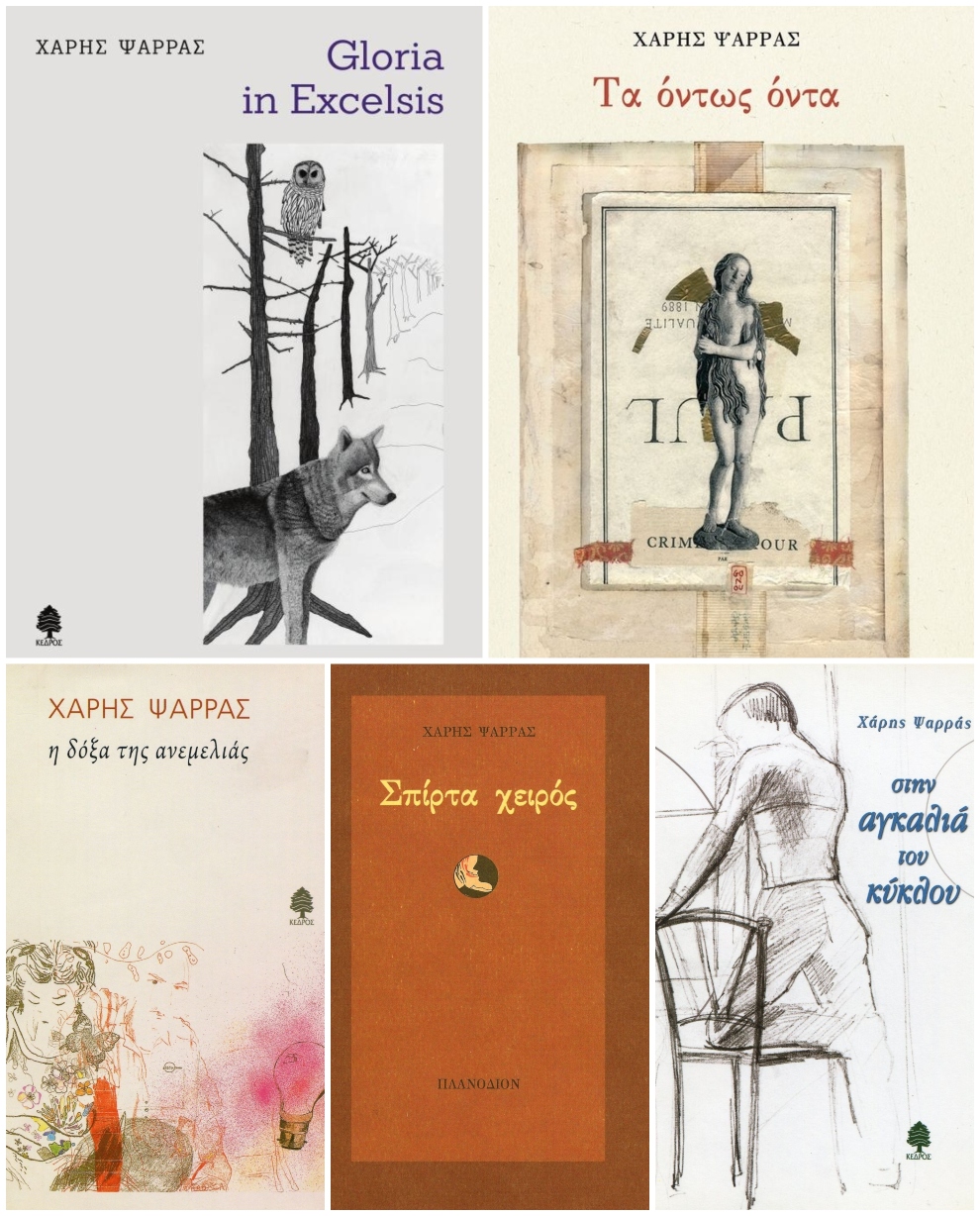

Haris Psarras has published five poetry books. Translations of his poems have appeared in anthologies and periodicals in Europe and North America. He has also contributed poems, short stories, and essays to journals and edited volumes. He studied law at Athens, Oxford, and Edinburgh. He has held academic posts at Edinburgh, Cambridge, and Southampton.

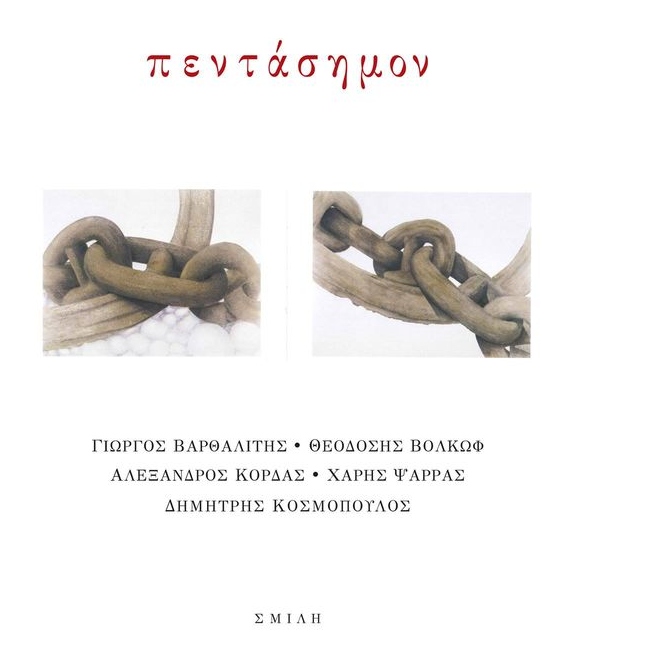

Πεντάσημον, recently published by Smili (2020), is a collective work of five poets united under “a common poetic perception”, that is a preference for verse poetry, in the words of Euripides Gargandoudis. Tell us a few things about the book.

Alexandros Kordas, Dimitris Kosmopoulos, Giorgos Varthalitis, Theodosis Volkof, and myself share an interest in the rhythmic structure of verse and the sonic features of poetry, including meter and rhyme. In Πεντάσημον (transliterated as Pentasēmon) we each collected a dozen previously unpublished poems. Though each one of us has his own style and preferences, we all treasure metrical verse, free verse, and prose poems. By putting together a co-edited volume in which all three of these poetic forms are represented we intended to make a statement: Form in poetry matters, but what form a poem is written in does not.

How would you comment on the ongoing debate as to whether and to what extent free verse is in crisis (some poets and critics defend it as the predominant form in modern Greek poetry, while others criticize or even reject it, as they attribute it to generalized amorphism)?

The current prosodic climate in Greek poetry is more complex than a polarised debate on metrical and free verse suggests. In fact, one can find notable contemporary Greek poems written either in free verse or in metrical patterns. Since the postwar years the majority of noteworthy Greek poems have been free-verse poems. But the number of good poems written in meter (or in meter and rhyme) or, more generally, in stricter prosodic forms —stricter than the open form of poetry that is normally associated with free verse— started increasing exponentially in the early 90s and has been at strikingly healthy levels ever since.

An argument can be made that free verse underwent a crisis in Greece around the 80s and the 90s. Though good free-verse poems were also published at that time, the rhythm and form of some among them were less innovative or less artfully crafted than, say, their imagery. Moreover, in the case of less promising free-verse poems, loose prosaic verse made line breaks strike readers as redundant or capricious, thus impairing the fusion of content and form that poets are normally expected to achieve. However, free verse overcame stagnation and regression quite quickly. More recently good free verse has been produced through the incorporation of metrical elements in free-verse poems as well as through the moderation or diversification of formal rhythmic patterns.

This refreshing free-verse practice in early-21st-century Greece owes much to the aforementioned revival of poetry written in stricter prosodic forms. It now appears that both traditions are developing hand in hand. The clearest indication of this is that a number of credible poets write some of their poems in meter and others in free verse or reinvigorate traditional forms while they also write poetry in open forms or in prose. This climate and level of achievement is highly satisfactory in terms of the progress of Greek poetry over the past twenty years and a sign of a promising future.

Since your first poetry collection in 2002 till today, almost twenty years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your poetic work?

Since your first poetry collection in 2002 till today, almost twenty years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your poetic work?

My approach to poetry has not changed. From the start I have had an interest in rhythm, imagery, diction, and in finding a balance between experience, emotions, and intellect. My intention has been to put together poetry books that would be divergent from one another in terms of content and style as much as it would be needed for each of them to have a distinct character and for all of them to serve the same poetic vision.

“The best poems are as unpretentious as the objects of the natural world and, at the same time, as subtle as the works of a craftsman”. In this respect, what purpose does language play in your writings?

Thank you for highlighting this remark. It comes from a note on poetry that I wrote for the Culture Now magazine in 2014. In an exemplary poem, language serves the purpose that I tried to capture in this phrase. When language is carefully crafted, but sounds as clear, transparent, and spontaneous as if it were not crafted at all, then the poem resembles a natural object, though it is an artifact. Of course, this happens rarely. Many good poets may feel that they have never got there. But trying not to fall too far below this standard is a formidable source of motivation.

How does poetry relate to the world it inhabits? Could poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Inspiration for poetry comes from experience, memory, and imagination. As such, poetry is a reflection of various representations of the world in poets’ minds and hearts. But it is also a reflection of various representations of the world stored in a language: the language which this or that poet writes his or her poetry in. Given that language (the medium of poetry) is more a matter of convention than mediums of expression in the visual arts, music, and other arts, and considering that breaking convention in language is often more challenging than in visual, auditory, and audiovisual communication, poetry can be said to be somewhat less receptive to what you describe as imagining ‘radically different realities’.

How do Greek poets nowadays converse with world literature? Where does the global meet the national/local in their work?

Since the early 19th century Modern Greek poetry has been in dialogue with poetry written in other European languages —mostly, in Italian, English, French, and German. Also, American poetry has been highly influential in poetry circles in Greece for most of the 20th century. Present-day Greek poetry is now more than ever under the influence of poetry written in the English-speaking world, which is perceived by some as more alert to current global-scale aesthetic, political, and moral challenges than poetry written in other languages.

Meanwhile, Greek poets who started publishing in the early 21st century have gained easier, faster, and wider access to foreign audiences than Greek poets of the 20th century. Unsurprisingly, when it comes to translation, English is the most popular target language. English translations of recent Greek poems have been widely published in anthologies and print or electronic journals. They have also been presented in poetry workshops, literary festivals, and performance art events in various countries in Europe and North America. French, German, and Italian translations of Greek poems written in the early 21st century are also remarkable.

Regarding the intersection between the global and the national or local element, it should be noted that modern Greek poetry has always been particularly open to cross-cultural blends that tend to emerge from such intersections. It seems to me that the three most significant reasons for that are (1) the global appeal of classical antiquity, which has been a source of inspiration to poets writing in Greek and in many other languages for over eight centuries, and still enables Greek poets to engage with the ancient Greek tradition through its representation in the work of poets from all over the world, (2) the Greek diaspora, which has been growing larger and even more successful in recent years, and (3) a particular set of socioeconomic and political circumstances in Greece in the post-war era and, subsequently, in the post-cold-war years; circumstances that have led to a reconfiguration of Greek national identity in terms of a cultural identity that incorporates Balkan, Mediterranean, European, and universal elements.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE