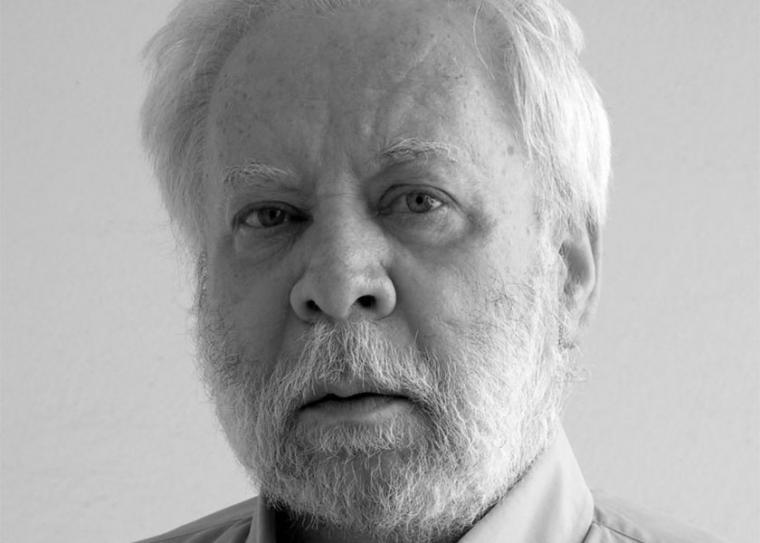

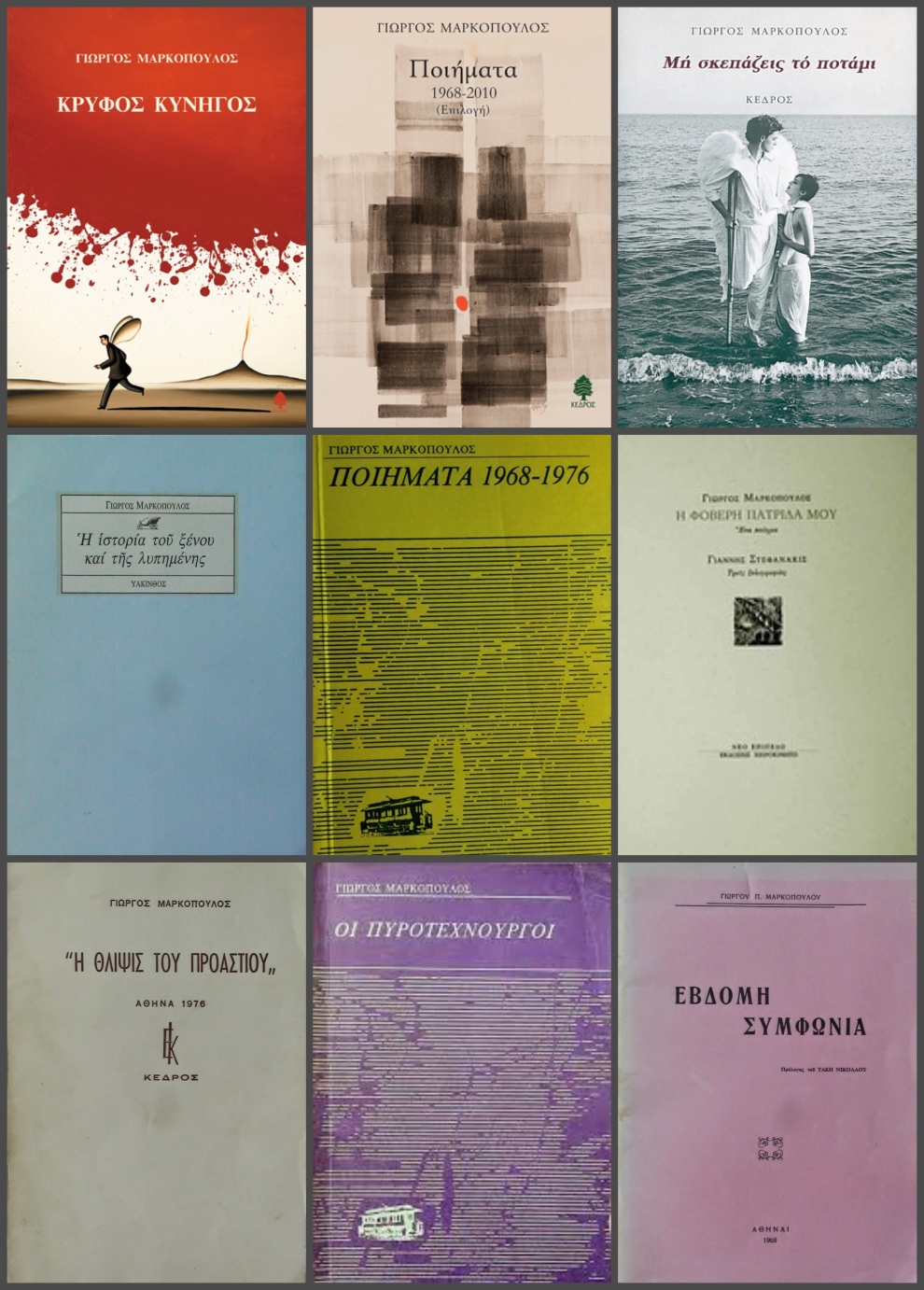

Poet Giorgos Markopoulos (born 1951) is one of the most important representatives of the so-called generation of the 1970s, a literary term referring to Greek authors who began publishing their work during the early 1970s. He has published seven collections of poetry, a book of prose, two monographs (one on the work of Tasos Leivaditis and one on football in Greek poetry), while he has edited a number of books on Greek poetry as well.

In 1996 he was awarded the Cavafy Prize in Alexandria, Egypt and in 1999 the State Prize for Poetry for his collection Do not cover the river (Kedros, 1998). A selection of his work was also translated by Michel Volkovitch in French and published under the title Ne recouvre pas la riviere (Desmos / Cahiers grecs, Paris, 2000). In 2011 he was awarded the National Prize for Poetry for his collection Hidden Hunter and, in the same year he was honored with the Award of the Academy of Athens by the Foundation of Kostas and Eleni Ourani for his entire life’s work. His work has been translated into English, French, Italian and Polish.

Poetry, prose, critical texts, monographies throughout a literary course of more than 50 years. What drove you to writing? Which remains your driving force?

What drove me to reading, in the first place, was a certain inclination I felt already from the first two years of high school, although a conscious love for reading came as early as my last years at primary school. As for writing, which gradually and quite unconsciously followed, I reckon that what drove me to it was my attempt to delve into unanswered personal questions, which could not be dealt with in any other way. This is what remains my driving force until today.

To use the words of Kostas G. Papageorgiou, “a poetry indicative of the mental, spiritual and ideological vibrations and emotional ups and downs of a man who is sensitive, fully socially aware and constantly exposed to the fires of an insidious and frightening reality, yet adamant in his decision to preserve as a valuable treasure everything that he feels that compose and keep his true face intact: memories of people, situations, old and new images that marked him indelibly, words that have halted – despite their fleeting nature – gestures and things that despite their objective perishability, work like fairy tales and strengthen him in his attempt to topically and temporally expand the present”. What is it that characterizes your poetry through all these years? Which are the main issues your writings delve into?

The words of Kostas G. Papageorgiou about my poetry are so insightful and profound that when I read them, I felt that this gifted intellectual person (and a brotherly friend whose death truly broke my heart) opened using his own key the door of my deepest self and brought back to the ‘hiding place’ of everyday life something that he saw there.

As for what characterizes my poetry throughout the years, I would say that it is what I have encountered in my life so far: agony about the human end, the awakening towards freedom in difficult social times, horrible memories from times of disease, the pain caused by love affairs coming to an end and in the last few years the mourning for those dear friends who left this world.

In my poetry, the souls of my parents are shining like two lights on a mountain at dusk, while those of my friends seem to form a whole town at the border of which there is a well, a deep well I have entered for four whole years and my beloved fought again and again hard to bring me back to the surface.

Simple and at the same time lyrical, apt and at the same time disarmingly simple, internal, often endoscopic. Could we say that it is empathy and compassion that characterize your poetic language?

Μοre than any of the characterizations you mentioned, I am flattered because indeed I consider empathy and compassion to be what lies beneath my writing.

I am a barber’s son and since I was five and a half years old, being his little assistant, I came to meet all kinds of human characters while I also witnessed all kinds of human pain, sadness and suffering, which quite silently led me to the way of tenderness and compassion that would accompany me in the years to follow.

You are considered one of the most important poets of the so-called generation of the 1970s. What differentiates this generation from what preceded and what came next?

I must admit that I don’t like the term ‘generation’ so much not only because it is quite abstract but also because it lumps together quite distinct poets, writings and qualities. Instead, I prefer to say: “the poets who appeared shortly before or shortly after the early 1970s”.

This considered, I would say that what differentiates us from the poets of previous decades is that most of us started by raising a strong voice against the dictatorship of 1967 which plagued our country. Gradually, according to his own temperament and talent, each one of us carved his own path, which also led to more internal landscapes, landscapes of the soul, as well as to a more comprehensive and meaningful poetic language.

I cannot speak for all of us, but as far as I am concerned, in my maturity, I drew my inspiration mainly from Greek poets, without of course neglecting foreign ones; from major poetic figures such as Solomos, Kalvos, Cavafy, Seferis, Elytis, Ritsos, Embirikos, Egonopoulos, as well as from all of those who wrote at the same time with them, until the late 1960s. I am really grateful to them all.

Poet Giannis Varveris wrote for you: “He may be the only poet of the generation that appeared in the 1970s that managed to combine the aesthetic emotion with the popular wisdom and thus remain from his early start to his poetic maturity the most aristocratic popular voice of his generation”. How does your poetic creation converse with the world it inhabits? Would you say that art constitutes an autonomous act or that is closely related to the historical background in which it takes place?

Giannis Varveris and I were brotherly friends since we first read our poems in 1976 at the second young poets meeting at the ‘Ora’ Gallery of Asantour Baharian until the moment – alas, that moment – that he left this world and you cannot imagine how many things I learned from him.

As for your question and his words for me, I don’t believe I deserve them; I am sure there are just words of love. But let just be it.

Regarding art, it is both an autonomous act and at the same time closely related to the historical background in which it takes place. A strong personality knows how to combine them all and offer us, in the end, something really true and beautiful.

As for my own writings, this combination has been there since my beginning; at first there was a tendency towards the exterior, until Πυροτεχνουργούς [Pyrotechnicians] (1979) when I consciously started to look towards the inside, without however neglecting the outside.

“If you don’t start by realizing this defeat against decay, time and death, I don’t think you can dive deep”, you once stated. What is it that makes you characterize the poet “as a person defeated by nature”, not so much politically but rather existentially?

It is exactly what you mention: the realization of the human end, which despite the ‘cloudiness’ and the bitterness of defeat that brings to the soul, pushes our soul to become better – indeed defeat does so. To love people, to understand them and most of all to carefully close the door of our friend, when we leave his house at night.

You remain active in current poetic affairs. What is your opinion about contemporary poets? Do they bring something new to the poetic art?

Younger poets are in their majority quite talented, composed and serious, precociously mature, who, from their early start, delved into more internal landscapes, what I call “landscapes of the soul”, so as not to lose valuable time until they are led to this way, which bears solid and undeniably timeless fruit to whoever is talented.

Yiannis Kontos, Veis, Varveris, Kostas G. Papageorgiou and I have loved these young poets very much and have helped them selfishly. As I used to say to my friends: “We received so much love from our elders and we owe to offer this love to the younger ones in practice and in time”. The three of them are now gone and the two of us, Veis and myself, who are still alive, do whatever we can with the strength of our pens.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE