Maria Laina was born in Patras in 1947. She studied Law at the University of Athens. She has worked in various jobs, all related to art (translation of essays and literature, edition of artistic, philosophical and literary books, broadcasts and screenplays on state radio-television, teaching Greek language and poetry in English colleges, teaching translation, writing in newspaper literary columns).

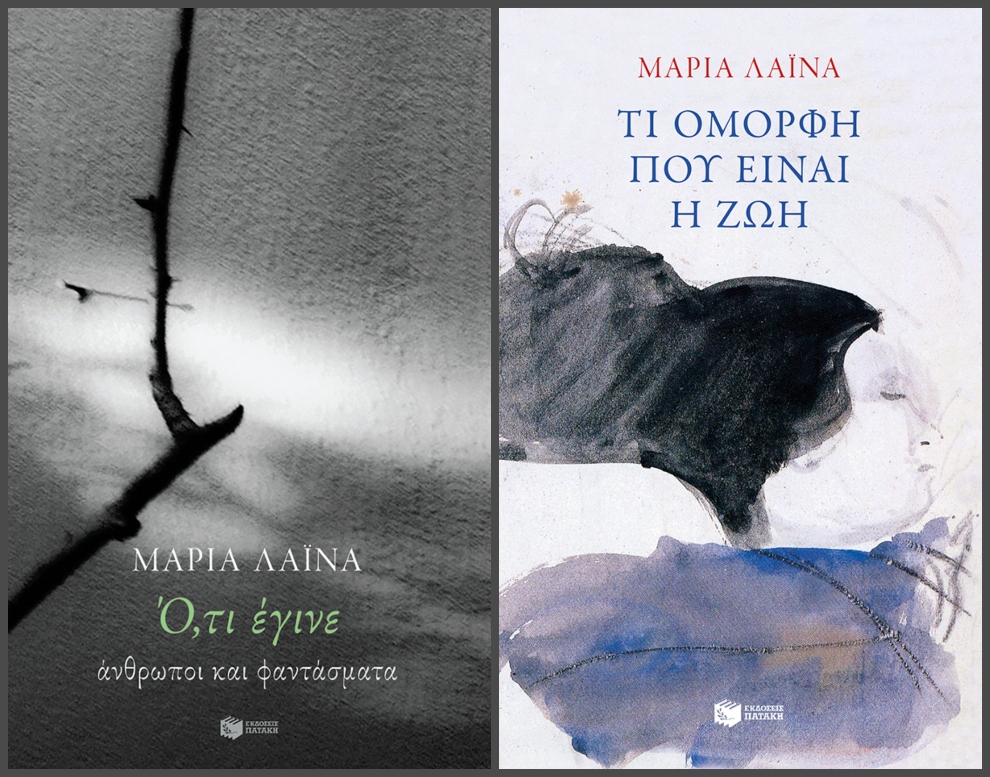

Her work includes nine poetry collections, eleven theatrical plays, five prose books, four critiques and studies, an anthology of 20th-century poetry (a selection of Greek translations). A one-volume edition titled Σε τόπο ξερό [On dry land], which comprises eight poetry collections, from Επέκεινα [Hereafter] in 1970 to Mικτή τεχνική [Mixed technique] in 2012, Θυµάσαι τι είναι ποίηση; Ιστορίες ποδηλασίας [Can you remember what poetry is? Cycling stories] (2018), fifty feuilletons titled “Pedal” written between 2009 and 2011 for the “Vivliothiki” column of the newspaper Eleftherotypia, the novella Τι όµορφη που είναι η ζωή [How beautiful life is] (2020) and the poetry collection Ό,τι έγινε [Whatever happened] (2020) are all published by Patakis.

Her books have been translated in various languages, either on their own or as part of anthologies. He has officially represented Greece both in the US and Europe on several occasions. She was awarded with the State Prize for Poetry (1993), the Cavafy Award (1006), the Maria Callas Award by ERT (Third Programme) (1998). On December 2014 she received the Kostas and Eleni Ourani Award of the Academy of Athens for the entirety of her work, while she received an honorary distinction for her contribution to letters and arts by the University of Patras, her birth place. The German translation of Ρόδινος Φόβος [Rose-Coloured Fear] by Dadi Siveri-Speck received the Munich Award (1995). Although unwillingly, she lives and works in Athens.

Your latest writing ventures, that is the poetry collection Ό,τι έγινε and the novella Τι όμορφη που είναι η ζωή were published in 2020 by Patakis. Tell us a few things about the two books.

Authors, you know, when they talk about something they captured on paper, fall into the trap, without necessarily a malicious intent, of describing that imprint as something they wanted to do or thought they did or thought they could have done if it weren’t for this or that X factor. Yet, the imprint, that is the body of the poetic or prose text, is there, on paper. And the psychological reproduction of the moment, of the instantaneous time– and this is especially true of poetry since we are talking about a mental image or verbal act and about the identification with the creator – cannot exist. In addition, poetry requires something completely different: to enable the reader to feel or even empathize with the result, at least in part. After all, absolute identification would be, if not impossible, rather boring.

Poetry, among the various kinds of written literature, is the pre-eminent vehicle of emotion and feeling, without of course, implying the absence of meaning. What I mean is that a poem is not and cannot be an idea, a well-designed figure, a concept or a project – innovative words that, as far as I am concerned, harass Art and at times harm it – in other words, it’s not necessarily the beginning or its end by definition. This is the reason why I avoid talking about the books I have written: I too would be in danger of giving the wrong impression and the reader would lose his/her own subjective view. Besides, every work of art should keep something of its secret.

Poetry, theatrical plays, prose, literary reviews and studies over a period of thirty years. What led you to writing and which remains your driving force? Which would you say is the binding thread of all those different means of literary expression?

First of all, I have not written studies or prose that exceed a hundred pages. I don’t think I have either the predisposition or the ability or even the mood, I dare say, to write something like that. There is no visible binding thread, at least for all those genres that are part of literary writing. The binding thread may indeed exist in what I write in a way that only an arrogant critic or reader, even myself, may claim to clearly distinguish or to have discovered. The only thread between poetry, short stories and theatrical plays, as far as I am concerned, is the economy, the density of speech and whatever listening ability I may have. The latter sound strange, but sometimes I keep silent and wait to hear what my fictional characters are saying so as not to impose my words on them. Now, in terms of style, I clearly believe it varies from book to book. I have this vice. Sometimes I look at poems or plays that I have written, in amazement, and at others I feel indifferent or puzzled. When I say puzzled, I mean that the following thought crosses my mind: “Did I really write this?” or “but what was I thinking of feeling when I was writing it?” or “how was I when I wrote this?”.

You have characterized poetry as a game, a rather serious game. What does poetry constitute for you? What is your relation with language and its musicality?

I cannot recall describing poetry as a game, not even a “rather serious one”. Although this may remind me of something I have actually said: that poetry, no matter how much aided it is by talent, is essentially something like an adversary at, let’s say, a sport. It’s of course a simile, though not entirely unfortunate: poetry also needs the right equipment, persistent and painstaking exercise, a current assessment of the opponent, choice of the most suitable ground (type of poetry), zeal, imagination, a balanced nervous condition, a quiet loneliness and a prudent courage. Last but not least, insight as to when “the game” is over and you should retire.

As for language and its musicality (I would prefer the word music because it includes its pauses that are an integral part of it, its sharps and flats, the meter and the tempo), others, much more competent, have eloquently expressed it. Mark Stand, a great contemporary American poet, had answered in a similar question that poetry is simply language. Everything else is intermediate gaps. And, much earlier, Mallarmé was even more strict when he said that poetry is written with words and not with ideas, which brings us back to the nonsense about project and concept. The music of poetry, then, is a component of the opting and matching of words, and unfortunately something is inevitably lost more or less (depending on the patience and skill of the translator) in translations. Some analogies should be observed because translations aim to the reconciliation of languages. Unfortunately, the Greek language (by the way, in Greece we rather write poetry than read it) belongs to the languages that are recognized by very few foreign speakers. Yet, I hope that something remains from the meter and harmony of its poetry in translations.

How does poetry relate to the world it inhabits? Where does the personal meets the social in your work?

Poetry is inextricably and in various ways related to “the world it inhabits”. It couldn’t be otherwise. I cannot write like the Ionians or the Aeolians, nor could they use our words. The material of poetry is words and language as it is formed over time. If this material is good, so much the better for the poet. If not, he should try to make it better. Now, as for the meeting point between the personal and the social in my work, I do not have it in mind when I write. There are poets who address the audience directly and can recite their poems in an open stage (e.g. Mayakovsky, and Sikelianos from the Greek ones) and poets who would rather address readers one by one. And if the result is satisfactory, that’s the meeting point. After all, isn’t society a set of people? The unit is a micrography of the entire. And aren’t the important issues or questions that concern us all more or less the same? Akhmatova did both. Tsvetaeva almost only the second.

You are considered one of the most prominent representatives of the so-called generation of the 1970s, the generation of doubt. What differentiates this generation from what preceded and what came next?

I am glad you began your question with “you are considered” since time is ruthless and – using another simile – let’s say that the value of a poet is a stock market share full of surprises. In Greece we had plenty of them. Let me remind you of the not so warm welcome towards Kalvos when he published his first poems, Karyotakis and so many others. On the other hand, we shouldn’t forget the almost concurrent existence of the Palamas School and how time reversed everything. I omitted Cavafy on purpose, who was so harshly criticized in the beginning, yet some had already discerned what would follow.

I don’t like categorizations, classifications by generation, gender or colour. Schools and movements are something completely different. Each one leads its own path; using its own expressive means, his own likes, dislikes and skills. I am not even sure about the term ‘doubt’. I personally don’t remember doubting something; perhaps only when it was presented as something more obvious than the obvious or when I pulled out something hidden behind the coating of the obvious.

How would you comment on the current literary and artistic production in the era of online communication? Could art be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

I wouldn’t like to comment. I am waiting to see what will happen, if of course I am still alive, until a clearer image is formed so that I can express an opinion. The only thing I can say is that am a book lover and that I will miss the paper, its texture and smell if we are overwhelmed by nonsense on the internet here too.

“Art to be used to imagine what could be radically different realities”, there is no such chance. Only the frantic ‘progress’ of technology has this potential. And the future is not bright. Freedom of movement has never been more inconsistent with the multitude of means at its disposal. At the center of all vital human interests is money, which, with is crushing effect, paralyzes almost every human relationship, while at a physical and moral level, it renders pure trust, peace and health even more difficult.

Could a multi-faceted socio-economic phenomenon, such as the crisis or the pandemic, trigger a new poetic ‘cosmogony’, which could possibly lead to a new poetic ‘generation’? If so, based upon which poetic and aesthetic criteria?

To begin with, I see nothing multifaceted in socio-economic phenomena. Quite the opposite. I see something completely one-sided. In addition, I do not see any possibility of a crisis “triggering a poetic cosmogony”, even when in quotations. There will certainly be new poetic generations. The poetic and aesthetic criteria will be decided by them and it’s not possible for me to predict them. But which cosmogony, if such cosmogony actually existed in the past, managed to subvert the beauty, the charm and the dense weave of the poem that I will quote below, which was written between the 6th and the 5th century BC and is attributed to Sappho:

Now read the following two translations, one that actually exists and a non-existent one:

Translation: Mary Yossi

and

Here there is everything: love, time, sadness, loneliness. Why this boldness of the potentially younger non-existent translator? Because the word hour means, already in Homer, not only hour (as a subdivision of the duration of the day), but also season (“the hours of the year”, in this case spring) and the flower of youth. So, what kind of cosmogony do you imagine can eliminate Sappho’s genius in choosing this word and its respective range of meanings?

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE