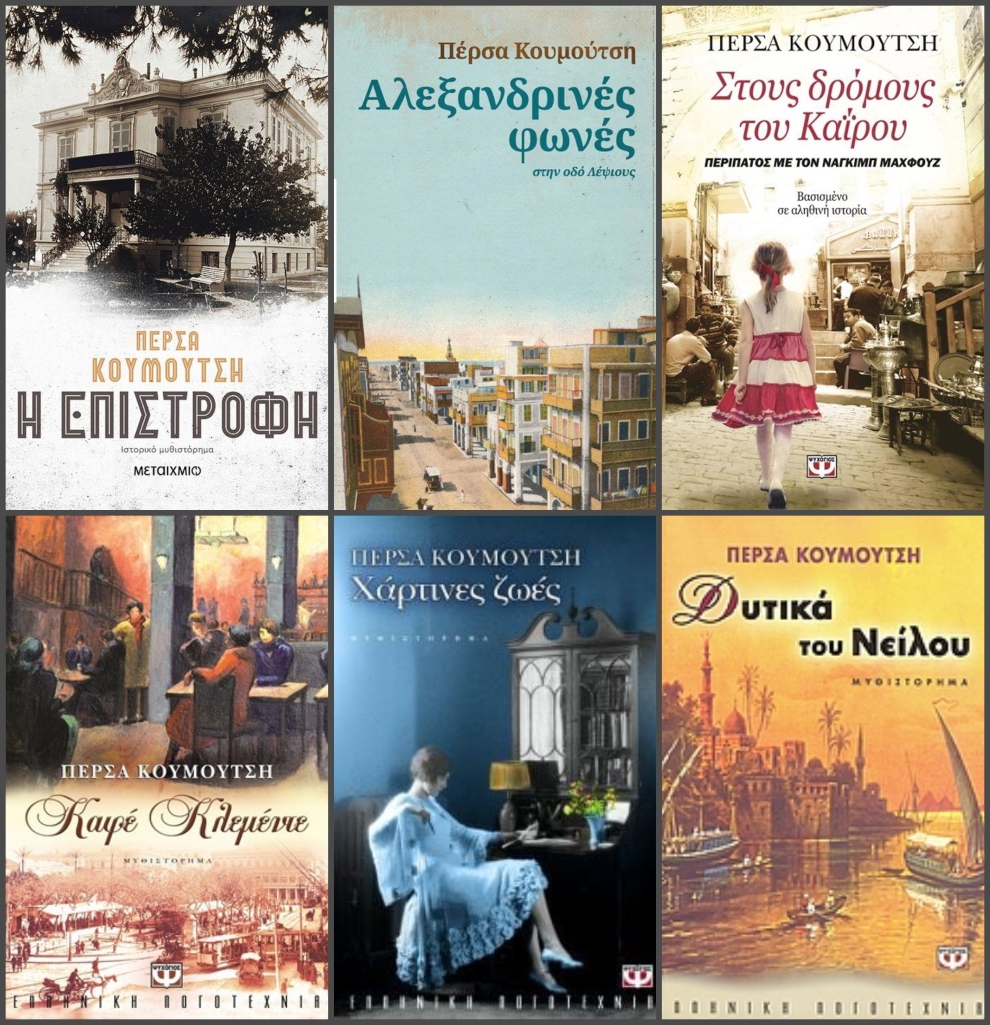

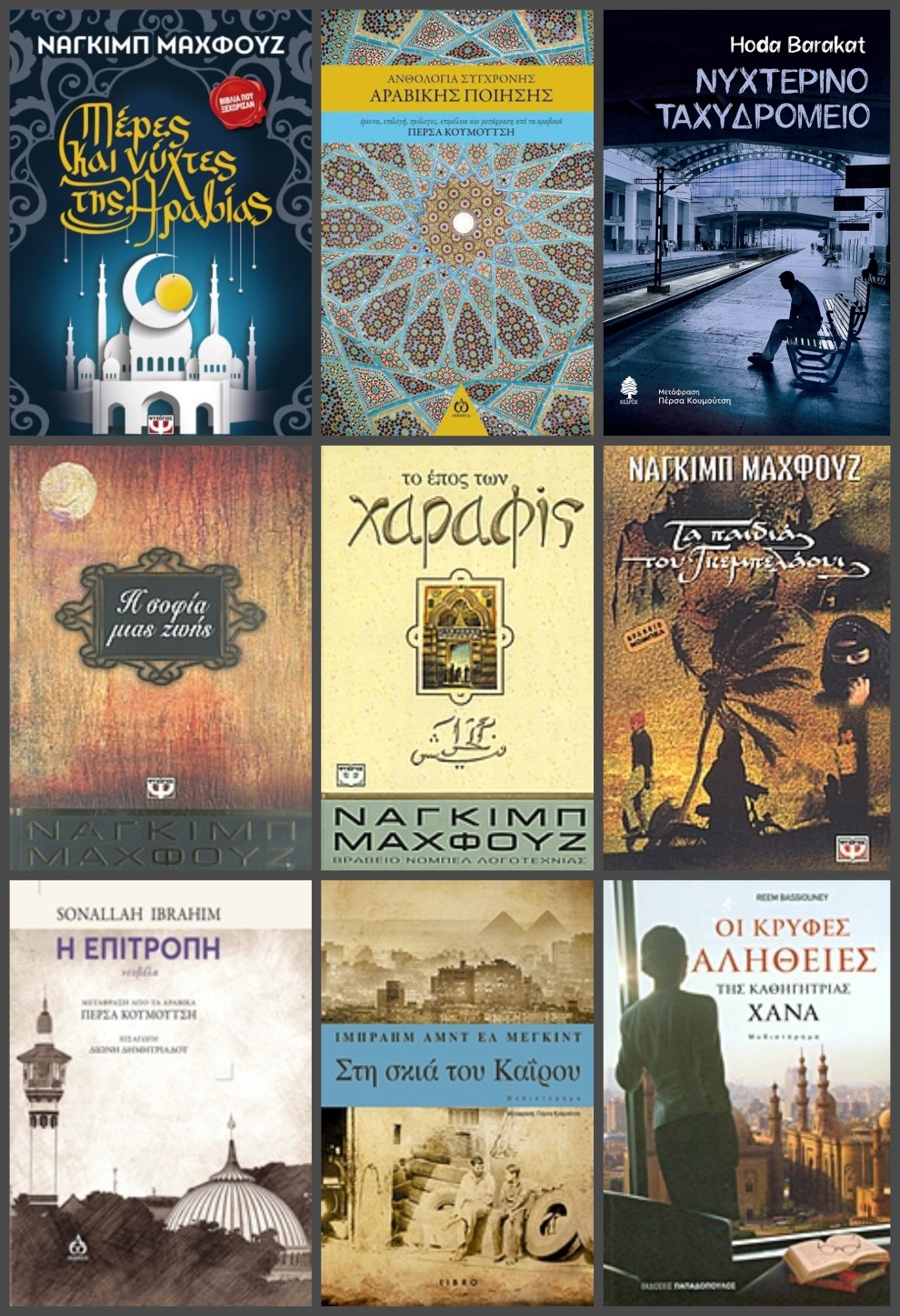

Writer, literary translator and essayist Persa Koumoutsi was born in Cairo. She returned to Greece after completing her studies at the Faculty of Arts of Cairo University. For the first few years she taught in Secondary and Higher Education, while from 1993 she works as a translator mainly of Arabic literature into Greek. Among the works translated from Arabic are 14 novels by the Nobel Prize winning Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz as well as many works by other distinguished Egyptian and Arab writers and poets. Her bibliography also includes the first Anthology of Contemporary Arabic Poetry in Greek, for which she received the Award of the Hellenic Society of Literary Translators in 2017.

She has been also been awarded the Cavafy International Prize in 2001 for her translation work, and received a special distinction from Department of Greek and Italian Studies at Al-Azhar University in 2015 for the entire body of her work, which includes more than 40 titles of Arabic literature both prose and poetry, and eight personal novels, most of which promote and are based on intercultural dialogue themes. Her personal work has also been distinguished and a significant part of it has been translated into Arabic. She collaborates with European universities on interculturalism and translation programmes. She has written articles, critical texts and essays on literature as a means of understanding the Other. Since 2020 she directs the Centre of Greek and Arabic Literature and Culture, which aims to strengthen the cultural ties between Greece and the Arab world, through targeted actions and programmes aiming to promote, inform and raise awareness on issues of contemporary Greek and Arabic literature, such as poetry, language, forging important cooperations with other cultural institutions in Greece and abroad.

Alexandria and Cairo during the interwar period, Cavafy, cosmopolitanism, the Greek community in Egypt, play a leading role in many of your novels. To what extent are your personal memories of your life in Cairo reflected in the writing of your books? How does the personal experience turn into a historical narrative?

Personal memories and experiences, history, the literature of the Greek community in Egypt clearly played and continue to play an important role regarding the themes and the atmosphere that prevail in my books. Yet, equally important in my writings has been my engagement with contemporary Arabic literature and, above all, the work of Nobel Prize winning author Naguib Mahfouz, which effortlessly penetrates almost all my books, sometimes discretely or subtly and at others more intensely or clearly, as for example in my book On the streets of Cairo, a walk with Naguib Mahfouz, which connects personal experiences with the literary heritage of Egypt. The autobiographical elements that govern the narration in the first part of the book are based on personal experiences, memories, and constitute the vehicle for the expression of emotions and thoughts, while the second highlights the influence of the great author’s work on the course of my life and my developpment both as a writer and as a human being, with many references to his work.

“Although I have been living in Greece for many years now, I still carry on me experiences and features common to those of the writers of the Diaspora around theworld, who, in their majority, cannot overcome three ‘woes’: the idea of ‘returning’ to the place of birth, nostalgia, and the conflict between here and there, before and after. They feel in limbo or divided between two conflicting, often contradictory forces”. Tell us more about these ‘woes’.

Of course, I didn’t use the word ‘woes’ literally. What I referred to were the obsessions that haunt a creator, a writer in this case. The writers of the Diaspora, indeed, cannot easily move away from these dilemmas, while they always move back and forth between two places, the one to which they culturally belong, but also the one that hosts them and which inevitably exerts the greatest influence on their formation and evolution.

You have characterized writing and translation as interrelated arts. Which is their binding thread?

I return to the book I mentioned above as it is a case in point. The novel moves on three levels. The first is personal or autobiographical. The second is historical, with reference to the modern history of Egypt, while the third level is philosophical, where Mahfouz emerges as the most important writer in the Arab world. “It is the combination of these three parameters that gives the book its great value at a literary level”, wrote, among others, Dr.Hisham Darwish, professor of Contemporary Greek Literature at the University of Cairo, in his critical note on the book.

On his part, Egypt-born director Kostas Ferris pointed out that apart from the experiences and the atmosphere of Cairo, the most important element of the book is that it creates a new genre, which may or may not be autobiographical, may or may not be fictional, may or may not be historical, but it is a book of rare beauty, above all it is poetry. It attributed its special traits to my Egyptian upbringing and education; I attribute them to the combination of the two arts I am engaged with, writing and translation, which are interwoven here in a unique way. Without my in-depth engagement with the translation of Mahfouz’s works, and my translation experience in general, the book could not have been written the way it did.

You have translated works by prominent Arab writers and poets, including the award-winning Naguib Mahfouz. What were the main challenges you faced in your year-long engagement with Arabic literature?

To be honest, although this may sound a bit extreme, the biggest challenge for me was to find the time to translate as many writers as possible. Translating from Arabic into Greek was and still is for me an almost natural process, since apart from the fact that both languages are very familiar to me, I have always practiced “translation”, even unconsciously, since I was a child, when I translated playing with the other kids on the streets, at school with my teachers, at university with my classmates, until it became second nature to me. I feel privileged in this sense.

You have said that what connects Greek with Arabic literature is that they both focus on human beings. What do the two literatures have in common? Where do they diverge?

I firmly believe that literature has no borders, nor is or should be separated since it constitutes a universal language that transcends tangible borders. Yet, if we are to speak of Arabic and Greek literature as a means for the dissemination of the special traits of a culture, then I could say with certainty that there are indeed similarities, mainly because the central axis of literature in general is Man himself with their experiences, hopes and dreams, or even their worst fears such as our mortality and so on. All these are topics that we encounter in world literature regardless of the identity each carries. Besides, we are not complete strangers, the Mediterranean and its History is our binding thread, providing inspiration and material to both cultures. Certainly, there are differences, but they are insignificant vis-à-vis the common purpose of literature which, to my way of thinking, is to promote humanitarian ideals and articulate a common language of emotions and truth.

How familiar are Greek readers with Arabic literature? And, in turn, what is the appeal of Greek literature to the Arabic world? How important is the role of translation in the dissemination of a literature beyond national borders?

Contemporary Arabic literature became widely known in Greek in the late 1980s – with the exception of only a handful of books of French-language Arabic literature, while the exoticism and the uniqueness of themes, linked to the specific geographical area, were the main criteria for the selection of the respective titles. The Arab world but foe few exceptions was portrayed through the eyes and books of Western writers, such as Bowles, Durrell, Tsirkas and others, but not through the eyes of Arab writers.

What contributed greatly to the shift in interest in Arabic literature were the translations of the Nobel Prize winning author Naguib Mahfouz, especially those directly from Arabic, which followed at a rapid pace after his award. It was through his books that the Greek reader was enchanted and began to wander in the paths of human activities, realizing that they are all familiar movements of life everywhere. Through his work, he managed to introduce in the heart of the reader the dream magic in its most exquisite version and composition, while at the same time he made the reader come to an unavoidable realization, that everywhere man is the same, while the world he portrays in his work, even in the smallest alley, is actually a micrography of the world in its entirety and refers to all human beings. Its great appeal did pave the way for more translations of Egyptian and Arab writers in Greece. The same happened with Greek literature. The great Greek writers who were translated in Arabic and other languages paved the way for the younger ones.

In general, could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

Certainly. Of course, it’s not enough to translate a literary work mechanically. If the translator isn’t familiar with the cultural background of the writers and the place where a literary work is born, or doesn’t have a deep knowledge of the language he/she translates from, the writer’s motives, his/her more inner thoughts which are often insinuated or not explicitly expressed, his/her ideology and so on, then the effort is far from complete and successful.

Quite recently a new translation funding programme, Greeklit, was inaugurated by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture. How important do you consider its contribution to the promotion of Greek literature abroad?

Extremely important! I consider it a great initiative that will soon bear fruit. Modern Greek book production is not widespread outside national borders and thus, this programme will help works that represent the Greek modern thought become more accessible or known all over the world.

Since 2020, you direct the Centre of Greek and Arabic Literature and Culture (K.EL.A.L.P.), which aims to promote and strengthen the cultural ties between Greece and the Mediterranean countries with an emphasis on the Arab World. Tell us a few things about the initiatives and actions of the Centre.

There are numerous initiatives, available at the Center’s website, among which meetings between Greek and Arab poets and prose writers, book presentations in both languages, while in our plans is an online (bilingual) literary magazine where writers and readers could upload their texts in both languages, so that they become known and accessed by Greek-speaking and Arab-speaking readership. We have quite recently also launched the ‘read in club for culture across borders’, a project that aims to present works which promote the intercultural dialogue between Greece and the Arabic speaking world and others that are related to European programmes of this type.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE