Regarded as one of the most influential Greek poets of the 20th century as well as one of the most important figures in Western poetry, C.P. Cavafy was born in Alexandria in 1863, at a period during which Greek communities flourished in many Egyptian cities. Yet the family’s prosperity was to be short-lived. His father’s premature death forced the family to seek refuge in England where he lived from 1872 to 1877. The years he spent in England were instrumental not only to the shaping of his poetic sensibility, but also in the formation of his cosmopolitan character at a period during which European modernism emerged with the appearance of figures such as Joseph Conrad, Thomas Mann and E. M. Foster.

His return to Alexandria did not last long since a military uprising took place in Egypt in 1882; Alexandria was bombarded and Cavafy was among those who abandoned the city to move to Constantinople. It was there that Cavafy wrote his first verses both in Greek and English, as well as prose in the style of encyclopedia entries. Among his first publications were: the prose piece “Coral from a mythological perspective” in the newspaper Constantinople, and the poem “Bacchic” in the journal Esperos in Leipzig. Both, like many other poems and prose pieces of his early years, were signed Constantinos F. Cavafis, and were later silently repudiated.

Around the end of 1885 the family returned to Alexandria, and Cavafy assumed various jobs. He obtained steady employment in 1892, when he was hired by the Third Circle of Irrigation, under British control, where he worked for the next 30 years. He continued to live in Alexandria until his death on April 29, 1933, from cancer of the larynx.

Cavafy traveled abroad only seldom in his adult life – four trips to Greece and one to England and France– preferring to stay in Alexandria, the city to which he was passionately devoted and where he could comport himself as its self-appointed flâneur. Although exceedingly private, Cavafy cultivated a circle of friends who were avid admirers of his poems, including notable writers and prominent literary critics in Greece, England, France, Italy and Alexandria.

The City

[C. P. Cavafy, “The City” from C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems (Princeton University Press, 1975). Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard]

During his lifetime Cavafy was an obscure poet, living in relative seclusion and publishing little of his work. A short collection of his poetry was privately printed in the early 1900s and reprinted with new verse a few years later, but that was the extent of his published poetry. Instead, Cavafy chose to circulate his verse among friends. This novel publication method rendered his equally novel poetry elusive and highly sought after.

The first canonical edition of his poems was published posthumously in Alexandria in 1935 by his heir and literary executor Alekos Singopoulos. During Cavafy’s lifetime, translations of his poems into European languages were rare, appearing most often in foreign-language anthologies of modern Greek poetry. A true translation explosion took place after the second World War and continues to this day, with frequent new editions, even in languages that already boast several prior translations.

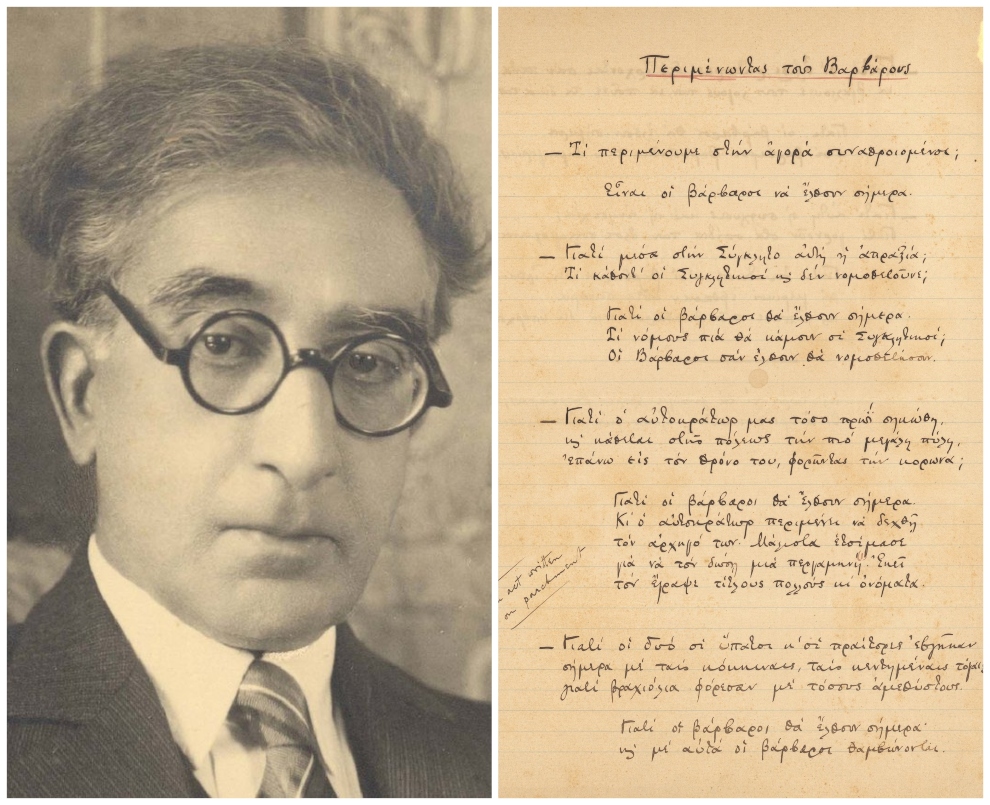

His entire poetic production was later grouped into four categories by G. P. Savvidis: the 154 poems of the “canon,” comprising the poems Cavafy himself put into circulation in his two “volumes” and ten “collections” plus one that was unpublished, but assumed to be ready for printing on his death; the “Repudiated” poems of his early period; the “Hidden” (which Savvidis originally called the “Unpublished”), which were not published in Cavafy’s lifetime; and the “Unfinished,” drafts of poems which the poet never completed.

Waiting for the Barbarians

[C. P. Cavafy, “Waiting for the Barbarians” from C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems (Princeton University Press, 1975) Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard].

According to criticism, Cavafy’s early poetry showed the influence of romanticism; he subsequently passed through periods of Parnassianism and symbolism, to culminate, in the longest and most mature phase of his work, in poetic realism. His ironic language is immediate and powerful, far removed from the obsessions of demoticism; his erotic themes are unapologetic; and the treatment of contemporary events by means of history is perceptible throughout his work. With his lifelong, unfailing devotion to the Art of Poetry, Cavafy spoke of love and death, of the violence and intoxication of power, of political opportunism and the failure of great ideals.

Cavafy was also an avid student of history, particularly ancient civilizations, and in a great number of poems he subjectively rendered life during the Greek and Roman empires. He was admittedly an historian manqué who always felt he could have written history had he not written poetry. What he produced was, in essence, a literary hybridization that combined both of his passions. In his essay “The Poetry of C.P Cavafy”, English novelist E.M. Forster hailed Cavafy for providing a compelling alternative to conventional renderings of ancient Greece, and he described Cavafy’s perspective as “intensely subject; scenery, cities and legends all re-emerge in terms of the mind”.

Cavafy’s more erotic poems treat themes similar to those addressed in his historical verses. Ultimately, Cavafy’s erotic poems and historical verse are products of a singular vision, one which explores, in various ways, the gratifications, and ramifications, of the pursuit of pleasure. Eroticism, history, and death are all part of what George Seferis, writing in On the Greek Style, calls “Cavafy’s panorama,” and he observes, “All these things together make up the experience of his sensibility—uniform, contemporary, simultaneous, expressed by his historical self”.

A.R.