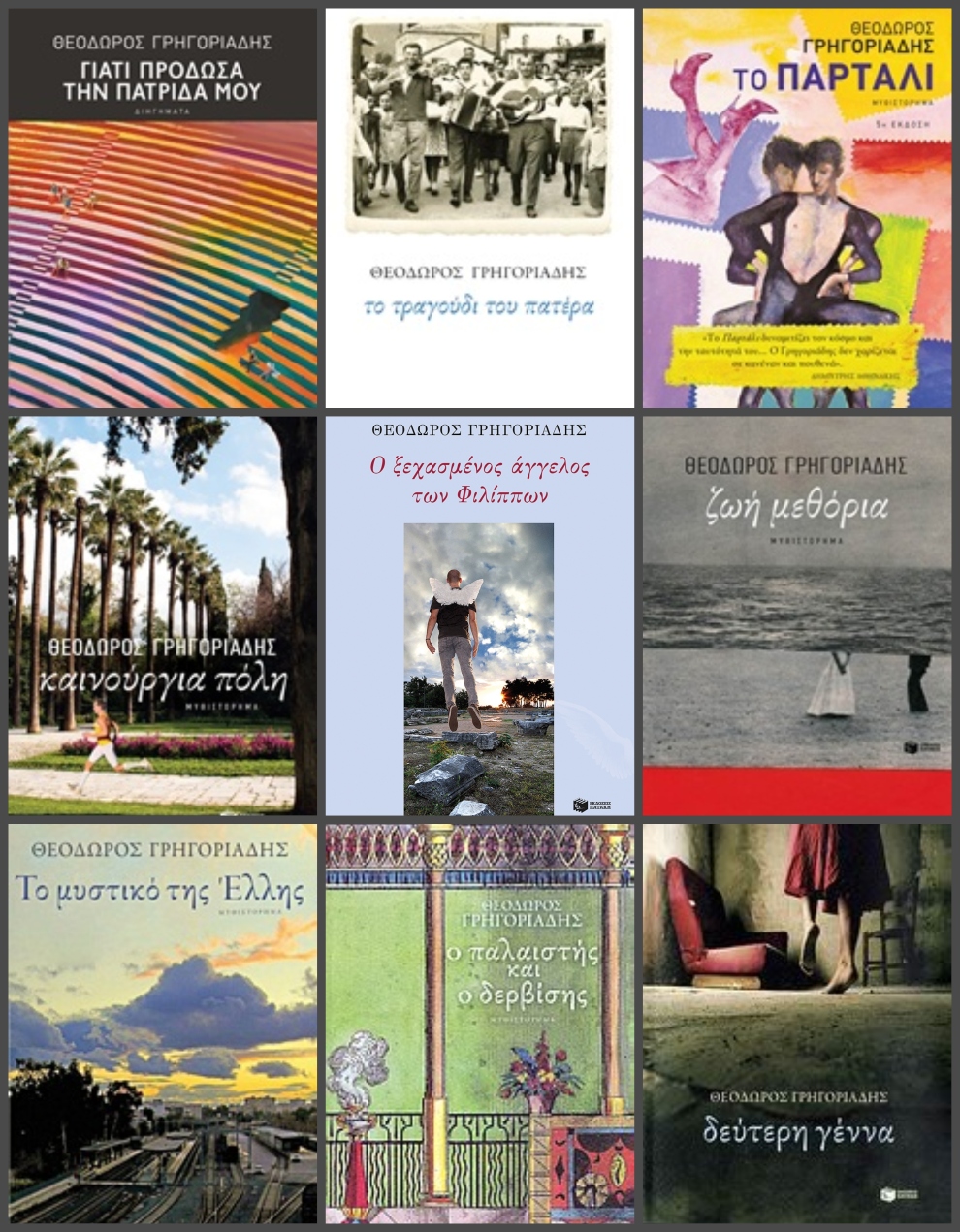

Theodoros Grigoriadis was born in 1956, in Paleohori Kavala, Northern Greece. He studied English Literature at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, taught English in state schools and co-operated with the Public Library of Serres for seven years. He has written eleven novels, four short story collections, a novella and a theatrical monologue. His novel Life at the borders received the State Literary Award for Best Novel in 2016, while The Father’s song received the Nikos Themelis Award of the literary magazine O anagnostis in 2019. His books have been translated in Egypt, Denmark and France.

He presented the documentary series “The reason for writing” on the Hellenic Parliament Channel. In 2019-21, in three cycles of literary seminars, he presented American authors in collaboration with the Athens American Center of the American Embassy. He is a member of the Hellenic Authors’ Society and PEN Greece.

Your new writing venture The nostalgia for loss is expected in spring 2022. Tell us a few things about the book.

It is a collection of thirty-one narrations. I opted for this word in the book’s cover instead of ‘short stories’ as it much better characterizes the narrative voice. Most narrations seem to arise from personal confessions and storytelling although there is also third-person recounting. It is a broad narration verging on a novel, divided in three cycles and an epilogue. Each cycle is united through a specific place (Northern Greece, Thrace, Library of Serres, Athens) and some characters that re-appear in different stories, while each narration cycle leads to the next. Love, loss, memory, mourning, laughter, sarcasm, adventure, self-consciousness are the themes that the numerous ordinary heroes of the stories are confronted with. Yet, there is another element which is more intense compared to my previous one: the bibliophilic one, especially in the second cycle that takes place in a public library.

Novels, novellas, short stories throughout a period of more than thirty years. What brought you to writing and which continues to be your driving force?

There are two different aspects to my writing career. Τhe apparent one, as a writer of books that have been published since 1990 and short stories published in literary magazines since the 1980s. Yet, there is also a hidden, uncategorized material which started long before and continues to this day: Diaries, notes, narration drafts.

This urge towards writing started at the age of fifteen and is due to reading literature. I was an avid reader, as a teenager, especially of classical literature. Now, if there is a gene that added to this inclination, I cannot say. Writing for me was something natural from the start. My studies in English Literature along with the rest of my readings further strengthened this course and gradually led me to create a writing persona, the one with which I continue to publish, without neglecting the writer of that other material, the more personal one. After all, a great part of those texts is used in my current stories.

“I am literary attracted to people, their peculiarities, their obsessions, their loves; I am interested in the other, the stranger, the different, our hidden self“. Would you say that this interest in human nature constitutes a recurrent theme, a kind of ‘literary obsession’, in your writings?

My material consists mainly of humans, their stories, people close to me, simple and strange, different and marginal. All people are interesting, they always have something to say when you are eager to listen to them. The stories I write, however, should concern me; they are not just drawn from the news or a distant surrounding. I reckon that I have given voice to dozens of characters all these years, is my so many stories. Gay and transvestite characters especially in Partali, the story of a cross-dresser or refugees and foreigners in The wrestler and the dervish as well as many women – they might outweigh my male heroes.

You have stated in an interview that your homeland is mainly its language, its culture, its literature and art. How are the notions of time and place defined in your work? What role does language play in this respect?

As I already mentioned, the human material is out there somewhere, yet the language tools are inside me. It is thel anguage that comes and gives voice; it is the way that shapes every story and every character. Those unique words, the phrases, the rhythm. Language has its secrets and it is both marvelous and challenging to look for it and expand it. Yet, contrary to the poet, I do not start with words and ideas, I discover them in the process of writing. Fortunately, the Greek language is rich; I spoke it, searched it and read it in numerous texts of different eras.

In some of your most recent books, there are references to the socio-economic conditions of the last twenty years. How has the recent socio-economic crisis as well as the current pandemic imprinted in your books?

Each of my novels represents a respective decade of my life. Especially during the last decade, it describes what preceded in Life at the borders and Τhe new city, and led both socially and financially to the crisis. Elli’s secret takes place at the beginning of the economic crisis and was characterized as representative of its era.

However, from the choices of characters, defense of the weak and minorities, especially refugees, becomes evident. The pandemic has not yet been depicted in my texts; it is quite early for that. Yet, my new collection The nostalgia for loss was written under the influence of the pandemic – I believe that it will appear in the thematic changes I have made. And just one, the last short story, talks about the days of the pandemic amid a sci-fi atmosphere.

Internationally there is a growing trend, called autofiction, which combines autobiographical elements, but with a dose of fiction. How is this trend to be explained?

Ιt was only natural that following the great fiction written by the classical realists at the end of the 19th century, modernism would bring about a different approach to narrative. In the mid-20th century, there were numerous first-person narratives that combined fiction and autobiography. Especially in France, there were quite a lot and it didn’t take us long to gradually integrate them into our own literature. What else could a first-person narrative be? A need to become more credible, to act as a testimony. Let’s consider the prose of Melpo Axioti, Giorgos Ioannou, Margarita Karapanou and so many others. In our times, when our whole life constitutes a daily post on the social media, auto-fiction is becoming more acceptable. We need personal testimonies, those short personal narratives and this is what auto-fiction offers; a sense of closeness and participation even in the guilt and the secrets of the writer.

Do you agree with those who argue that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives?

Indeed, there is a strong tradition in short stories that starts from the early days of Greek prose. It may be due to the Greek temperament, our climate and geographical position, our habits. Long narratives have found no place in Greece. Let us not forget how close to short narrative were our demotic songs, the prose songs, how vivid a story they told. Most Greek writers start by publishing short stories in magazines. Yet, we must admit that short stories are not popular on commercial terms. Literature is one thing and the market is quite another.

How do Greek writers converse with world literature? Where does the global meet the local/national?

Greek literature has always “read” and was informed of foreign literature. We have a large number of translations from every country; in this respect we are at a very high level. Influences are more than evident in crime and fantasy fiction. Auto-fiction also begun to penetrate our prose, while migration and refugees as a global problem also provided Greek writers with enough material. Unfortunately, though, due to the lack of translations of Greek literature, our own contemporary literature has little effect on contemporary foreign literature. Whatever influences are traced back to the ancient Greek literary canon. Foreign writers, instead of reading Greek literature, prefer to be inspired directly from our country and especially our islands; an ‘islomania’ as Lawrence Durrell eloquently put it!

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE