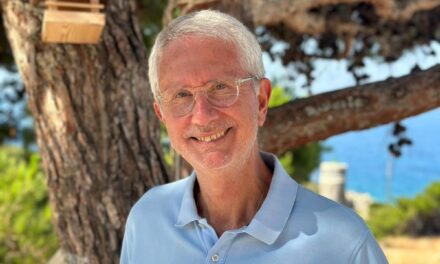

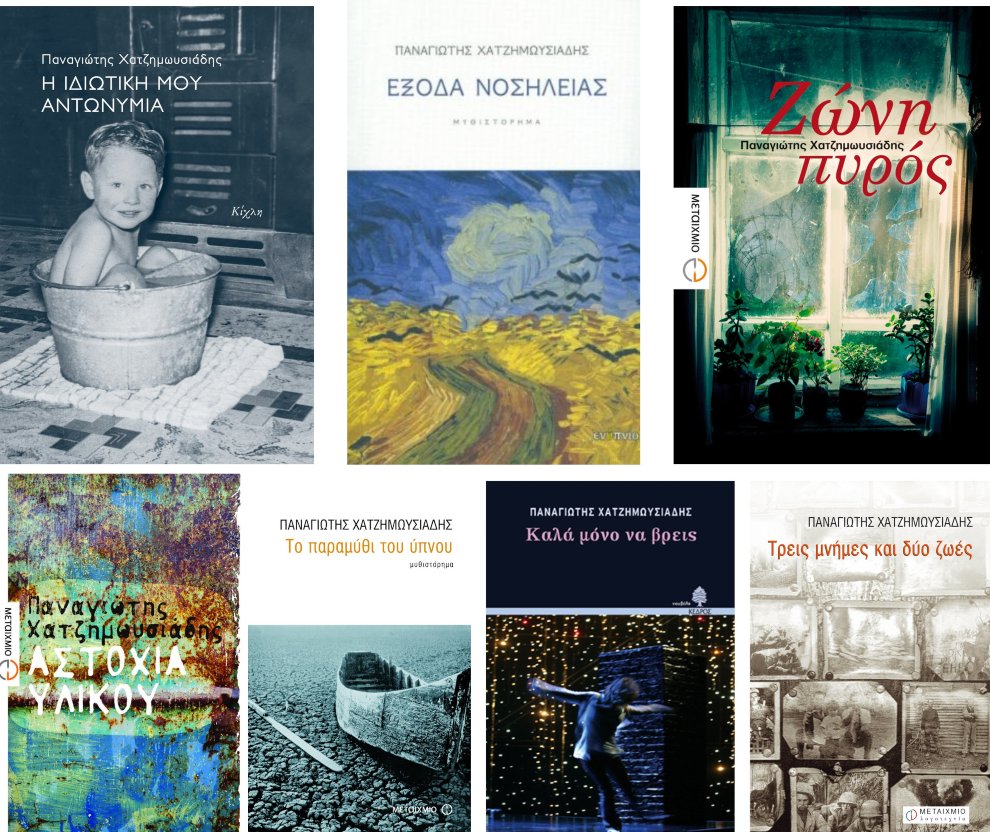

Panagiotis Chatzimoisiadis was born in 1970 in Dytiko, Pella. He works as a high school teacher. He received the Special National Prize for Literature 2021. He has published the following books: the short story collection Three Memories and Two Lives (Metaixmio, 2005), the novella Good is What you Find (Kedros, 2006), the novel Τhe Tale of Sleep (Metaixmio, 2008), the novel Hardware Failure (Metaixmio, 2010) the short story collection Fire Zone (Metaixmio 2014), the short prose Μy Private Pronoun (Kichli, 2018), the novel Medical Expenses (Enypnio, 2020), the novel The Snow of Agrafa (Kichli, 2021).

Short stories, novellas, novels throughout a period of almost twenty years. What has changed and what has remained the same in this writing course? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your books?

The first book contains, as it has been argued, all the following, that is to say, even in raw form, the thematic patterns, the technical features and the linguistic choices of the writer. Looking back at my collection of short stories Three Memories and Two Lives, published by Metaixmio in 2005, I can indeed say that the social look, the realistic writing, the oral style still characterize me. On the other hand, I would remain static, just repeating myself and thus be literary disarmed if I were content with the same and the same. My aim is to set the writing bar higher, to test my limits, to stretch the endurance of language, to enrich my prose both thematically and technically.

I must admit that from time to time I flirted with postmodern writing, at others I turned to a meta-realistic narrative technique, while I also tried dialectical linguistic forms and essays, and I enriched social issues with an existential and erotic content. Lately I find myself struggling with humor, which have tortured me for long, but I am still not willing to surrender.

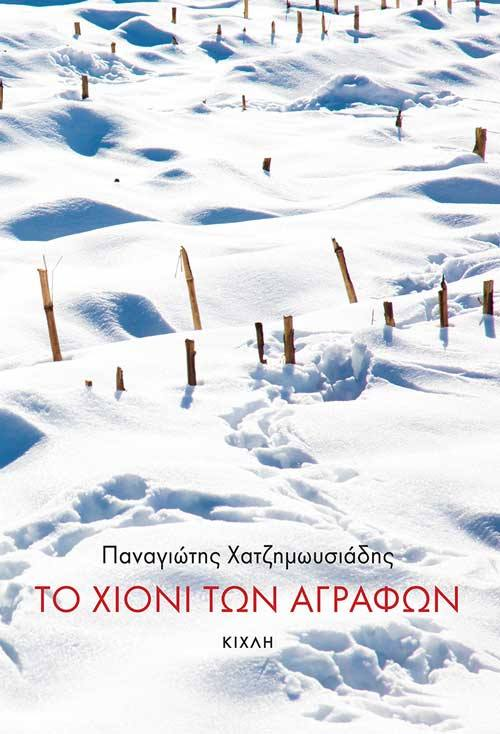

Disillusionment, ideological collapse, vain hardships, death are among the main themes your latest book The snow of Agrafa touches upon. Tell us a few things about the book and the way it converses with history. Where does the collective meet the personal, where does the political become existential?

1948 was a crucial date for the outcome of the civil war with the tide turning in favour of the National Army and the internal processes of the Democratic Army with the gradual marginalization of Vafiadis and the old ELAS chiefs. This double “civil war” between the Democratic and the National Army and within the Democratic Army was quite dramatic and became even more explosive in the case of the Unarmed Brigade, which started on February 18 from Agrafa to transfer reserves to Macedonia. This dramatic course under conditions of frost, hunger and the relentless pounding of the National Army I narrate in my book, trying to stay as close as possible to the historical events.

Of course, let me note that I am a writer and not a historian, which means that I always put the aesthetic dimension as a first priority through the fictional coverage of historical gaps, especially when the focus is not on the main characters of the course but on invisible militias and when my intention is not to do politics but to highlight the human, existential and political drama, so that through the Civil War I can talk about our time and the human cause over time.

More generally, how does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to shed light to unknown historical moments and make them accessible or even more comprehensible to a broader public?

I write in the basement of my house, in a rural community of the municipality of Pella, where I live, and I prefer the very night hours for reasons of devotion. But what seems here as a kind of privacy and detachment from the world around me only describes the act of creation and not my relationship with the surrounding reality. Like so many other writers I am a hiker, a reader and a listener, while I also happen to be a teacher, I have two daughters and I never stop being a citizen of a country. I draw my material from others, the world that surrounds me is my source of inspiration, based on my belief that the ego is understood only in its historical and social context and always in relation to the self.

The study of history lies within this framework, given that no literature is made in the absence of history even if the literary topic is far from historical. Literature can shed light on minor historical events, bring the history of the invisibles to light, open cracks in the body of the official historical narrative, turn the past into a living present or make the present a valuable source for the historians of the future. Thus, not only its aesthetic but also its historical responsibility is pivotal, and as a teacher I reckon it could prove valuable, setting historical teaching at school free from the deep yawns that it usually causes to students.

Critics have commented on the power of your literary language, the beauty of your literary speech. What role does language play in your writings?

I do not have the right to judge what is said about my work, so let me just say that in my aesthetic perception prose is less a subject and more a technique and language. The best subject is buried when the other two parameters lag behind, and what may seem like the most boring topic at first, can yield a great book when language and narrative take it to the next level. As far as language is concerned, let me note that I do not wish to treat it as the underlying thread of narration, neither do I want to reduce it to a simple tool of the plot. In my perception, it constitutes a major aesthetic parameter of the aesthetic whole, which requires care in terms of rhythm, melody and tonicity, even in the case of prose – hence my belief that a novelist has a lot to gain from his apprenticeship in poetry.

“Literature is not just an activity among others. For me, it is a necessity of life, a kind of balance and communication, defense and resistance, beauty and pain”. Tell us more.

I was quite moved when one of my students confessed to me that during a deep psychological crisis, it was literature that kept her upright. In a different context, this is exactly what I experience myself when writing. I mean that for me writing is not a technical activity, a means of self-promotion or ahobby but rather a need for expression, communication, action and, above all, life. It’s through literature that I exist as an aesthetic, political and individual being, it’s there that lies my dream and my hope for the world, its there that lies my existential anguish, my stubbornness and endurance, it’s there that lies my offer and my imprint.

Do you agree with those who argue that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives?

There is no shortage of great novelists – I will avoid mentioning names because I will be unfair to some. But for various reasons, mainly related to history, the absence of a strong bourgeoisie, the tradition of literature, the means of its dissemination (eg newspapers in the past or the internet today) it is in the short form that we have excelled. And I do not think that’s necessarily bad, since brilliant texts have not stopped being written. Let me note that the short form allows prose to approach poetry, while it also enables hybrid forms of longer narrative to be written, such as the composite novel.

“Writing and reading have always been a lifesaver for me and I could not help but wear it now faced with rough seas”. How has the current pandemic affected both reading habits and publishing trends? In turn, what role is literature called to play in times of crisis?

Very good books that were published during the pandemic never reached readers, the activity of small and medium-sized houses was reduced, while for various reasons the public didn’t take the opportunity to turn to books to a great extent. On the other hand, the use of electronic media has left a valuable legacy, since the absence of traditional ones has proved their value in our conscience. Restrictions imposed proved in practice that the literary obsession of the previous decades on confined spaces, on introspection, on the sad choice of loneliness, have their limits. Sincethebeginning of my writing career it is my firm belief that literature is a public aesthetic expression and this public character weighs both upon literature and its creator, even more in times of crisis. When the aesthetic pleasure is accompanied by the awareness of this burden, then I think we are talking about great works.

Thank you very much.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE