Michalis Sotiropoulos is a historian of modern Europe, currently employed as a post-doctoral researcher at the Research Center for the Humanities in Athens. He received his PhD in History from the University of London and has taught at the Universities of London and Athens, while during 2016-17, he was a post-doctoral research associate at Princeton University. His research interests lie in the history of ideas in the long nineteenth century, with an emphasis on Southern Europe. Greek News Agenda* had the opportunity to interview him on the intellectual origins of the Greek State, Greek liberalism and the historiography of the Greek revolution of 1821.

Your research has focused on the trajectory of Greek liberalism in the 19th century. What are the main features of this ideological current and how did they help shape the Modern Greek State?

This is the basic question I posed when I started my thesis. It took me about four years and 250 pages to reach a conclusion. Let me start by saying what Greek liberalism was NOT. And I start from this because one of the greatest problems of Greek historiography is its reluctance to shake some of its many foundational myths. In my case, it is the pervasive ‘modernisation’ saga that unfortunately does not inform only historical scholarship. How often do we hear about Greek society lacking this and that compared to ‘Europe’, about Greeks being unruly, and so and so forth? Apart from the rather underdeveloped comparative skills they show, such arguments and the outdated epistemological frameworks on which they are based do not advance research. Although many European historiographies have abandoned these frameworks, to a large extent we have not. And the crisis added insult to injury.

So, the problem I faced from the outset was that for most historians, Greek liberalism was backward, underdeveloped, not more than a bad copy of some ‘core’ European or Western liberalism. But this last thing is a post-war historiographical fiction. As historians have for some time argued, liberalism included different currents (conservative, elitist, moderate, radical, you name it) and was a political language -and this is the word increasingly used and not ideology- that was open-ended, heterogeneous, inclusive but also conscious of and adaptable to local political contexts.

The primary contribution of my research is to put Greek liberalism into this discussion. In doing so, I came up with a rather complicated picture. First, Greek liberalism was not only alive and kicking in the 19th century. It was also rather original. The reason of course was that the political context—that of the making of a state that had come out of revolution and secession from an empire—was rather original. That was also what made Greek liberals be rather eclectic in the intellectual sources they drew upon. The result was very rich: a fusion of liberal idioms of their times with Enlightenment civilizational discourses that took a new life after the 1820s.

A second feature was the heterogeneity of Greek liberalism. And it was this feature that made it into a versatile force in nineteenth-century Greek politics. To be sure, they were things everyone agreed on: the emphasis on rights, putting checks on power, the press, an active civil life, on European civilization and its right to rule over ‘underdeveloped’ or uncivilised peoples. More importantly, Greek liberals did not embrace a narrowly understood legal individualism. For them individual rights originated in law and political institutions, not against them. They thus embraced the state and the monarchy seeking to transform both. In other words, Greek liberalism was developed as a language of statehood, an idiom that legitimised the state and did not seek to put limits to its exercise of power.

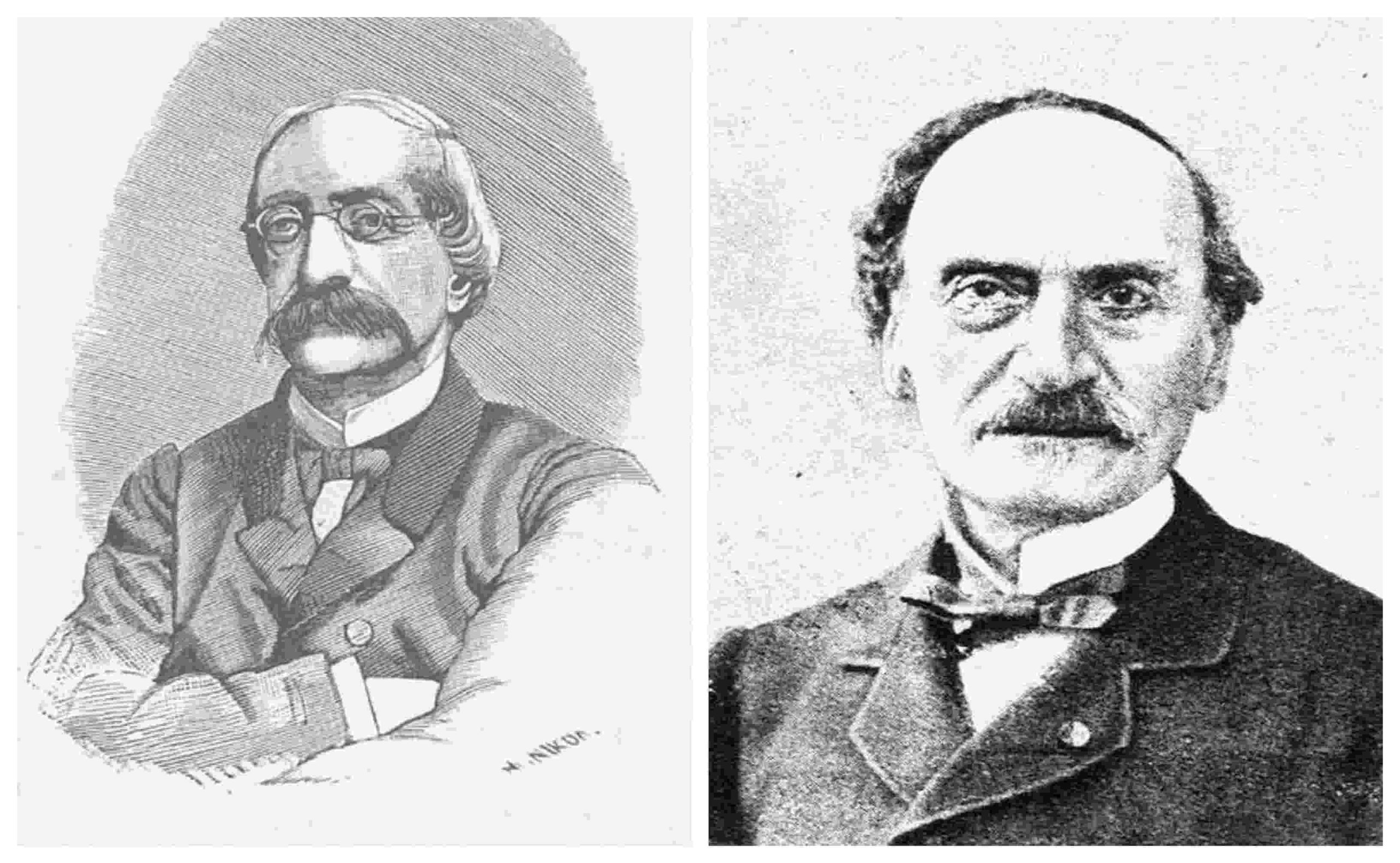

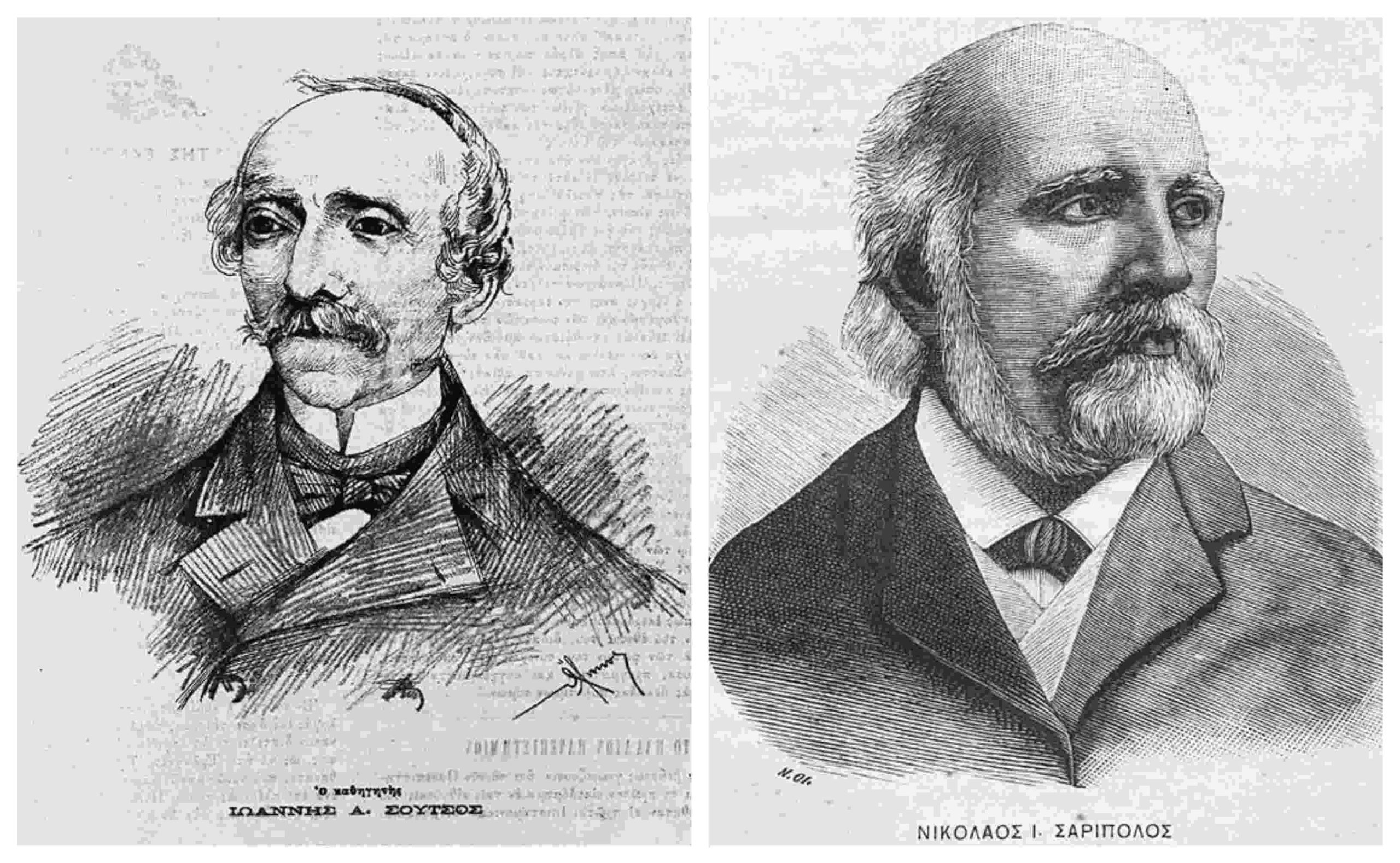

But it was here, on the state and its relation with society where strong disagreement occurred. Some liberals, like for example Pavlos Kalligas, Markos Renieris, or Petros Paparrigopoulos (mostly civil lawyers, the ‘Romanists’ as I call them), developed an elitist or ‘contractual’ current that focused on two ideas: private property as the material foundation of a strong and independent society and a rule-based administrative state (‘Κράτος Δικαίου’, Rechtsstaat) that would work as the manager of the country—a provider of services rather than an embodiment of power. It is important to note that these scholars never questioned the sources of political legitimacy of the monarchical state, but sought to transform it through nonpolitical reforms.

Others such as Nikolaos Saripolos or Ioannis Soutsos developed a more radical current, the ‘constitutionalist’. Drawing on the revolutionary tradition of rights and national sovereignty (J.B. Say, Sismondi, ‘industrialism’, Benjamin Constant, but also eighteenth-century sources) and trying to make individuality compatible with the national state, these scholars shifted the emphasis from personal freedom to the rights of society and the ‘public’. Worried about rulers concentrating power, they sought to expand political participation and crucially to put more contestation in the representation of national sovereignty. These scholars, spoke in terms of sovereignty as self-rule and of the state as a moral person.

What was probably more important in the long run was that these ideas informed a ‘transformation of thought’, which, in light of the failure of monarchical policies, was made into a political alternative to monarchical statehood. This was developed through a jurisprudential and political activism, politicking, participation in the government, as well as through their prolific writing and teaching. These were not armchair liberals. They played a key role in the major political transformations of the era and especially in the revolution of 1862 (a long liberal moment that saw the formation of the opposition against King Otto, and a constitutional revolution that lasted more or less until 1875. In that sense, the way I see it, Greek liberalism provided the intellectual foundations upon which the nineteenth-century modern Greek state was built.

Would you argue there was a difference in the conceptualization of the State between Greek and other European liberal currents?

It depends on the comparison. In general, I think that Greek liberalism has many common traits with continental liberalism. But compared for example to the French, Greek liberals were more attentive to the revolutionary tradition. That is not to say that they were necessarily radicals. The Romanists were not. This became clear even during the period of the Constituent Assembly of 1862-64, when they opposed efforts to expand political participation and representation and fell back to advocating very narrow property qualifications in suffrage. And yet, like the German Rechtsstaat thinkers of the 1840s and 1850s they stood to the left of the French Doctrinaires.

The same goes for the more radical strand, the ‘constitutionalists’, for whom central concern was how to give political expression to national sovereignty eliminating, at the same time, the chance of the usurpation of this sovereign power. In emphasizing political participation, public action and a robust political life, they were influenced by Constant, and Tocqueville among others. And yet they stood to the left of them as evidenced by several propositions they made: the need to expand political participation and to give expression to different opinions and partial interests, or the importance of political institutions and of the state for the welfare of the citizens. To these we should add the two key arguments that played out in the revolution against Otto: the criticism against the curtailed sovereignty which the Great Powers had imposed on Greece; and the claim that royal power was part of the sovereign power of the nation, not external to it or neutral, as the 1844 constitutional arrangement (and Constant) had it.

What were the main ideological opponents of Greek liberalism at the time? Were there competitive theoretical currents with different social origins in the Greek public sphere?

Although we need more work on that, I think that the main ideological opponent was the Bavarians. We are not used to seeing intellectual opposition as something important for the period, but gradually the main opponent was not the monarchy as such, but its specific ideas of governance. These were informed by the theory of the Police state, the Polizeistaat, which was associated with ‘enlightened absolutism’ and aimed at enhancing the ‘happiness of the state’. This last one was not understood in terms of individual self-realisation but in terms of the ‘well-being’ of the ‘population’. Although liberals formed their visions against this political technology emphasising individual virtues and rights, they never lost sight of society, the ‘public’ and in particular of the role of the state. The reason was that they saw the state as an agent of an alternative liberal governmentality that would ‘produce’ a national economy based on private property, and a contractual legal framework. More important in the context of a failing monarchy, was the constitutionalists’ claim that the nation as sovereign should be on its toes, in case its power is usurped. In other words, for them the right to revolution was a constitutional right.

Were you able to discern cases of personal ideological transformations? Or would you say that the positioning of 19th century intellectuals in Greece was static?

If there is a word that these scholars would probably NOT have known is the word static. And this should not be considered as a disadvantage. Ideological rigidity could not be part of their way of being in the world and of their thinking. We should not forget that they were key players in a political project which was in the making—we should not forget that the very existence of the new state, its survival and its changing conditions of being were questions that needed different at times answers. In such conditions, rigidity was a luxury they could not afford. It is easier today to be sure. Apart from this structural, so to speak reason, there is also a sociological reason for their intellectual flexibility. These were people who were children of the Greek revolution in the sense that they had to move because of it—they were too young to participate in it. Saripolos moved from Cyprus to Trieste, Kalligas from Cephalonia to Trieste, Rallis from Istanbul to Vienna etc. This mobility characterized also later their professional lives. At times, they were lawyers, judges, professors at the University, ministers, members of legislative committees. In a way they personify what Giorgos Dertilis has identified as a trait of Greek society, which is difficult to translate: ‘πολυέργεια’. When you are a master of many trades, it is not very easy or practical to be ideologically rigid. You see, multitasking was not invented in the 21st century. But if there was a change that was the most important was in their attitude towards the Bavarians. The reasons were of course ideological. But they were informed by the crisis of the 1850s-60s, and the failure of monarchical policies. A failure that jeopardised the already precarious place of Greece in the geography of European civilization and possibly its very political existence. Something had to give and it was the King.

You have suggested that the antinomy between legalist views of freedom and more substantive understandings of its social conditions remained at the heart of Greek political debate until 1974. Do you discern changes and continuities in the post-1974 period?

I am not a historian of the metapolitefsi period. And I don’t think that history has lessons to give for periods closer to our own. Different periods, different contexts, different questions, different answers. Yet, what I can say, because I am a member of this society is that, as evidenced by the crisis (financial and the so-called refugee) the substantive understanding of freedom is alive and well—thanks to grassroot mobilisations, to local initiatives, to people’s political engagements. What has changed is the non-articulation of this understanding within academia. Although this is not a general phenomenon, I am afraid that the discourse generated by some of the most relevant departments is troubling: positivism without critical engagement, and a sterile combination of methodological nationalism and Euro-centrism which ironically does not follow European trends. University and society are parting ways, so to speak. The same goes for the relationship between society and the established political class. It is amazing to see the extent to which some established political circles, most of them self-designated liberals, speak on a level of abstract generality and become anxious when this is abandoned. Think for example the continuous reference to the ‘people’, or the nation, and the fear when this ‘people’ sets out to express itself—though political movements, local initiatives, grassroots mobilization, referenda etc. Why? Because at these moments that abstract category becomes sociologically specific. For these liberals, this is dangerous, because it shows that there are social differences, inequalities, that the whole edifice of national unity is artificial.

The interesting thing is that such an anxiety is a legacy of the French revolution, not the Greek one. In fact, in Greece we have a long history of competing political currents with open and sometimes completely different views about Greek society and the social groups they stood for. For these currents people had specific characteristics. But today, the obsession with ‘consensus’ leads to an avoidance of disputes or of opposing alternatives. This is like trying to get rid of politics. Greek liberals of past times would never have understood this. Because they understood that a legalist understanding of freedom is too narrow a vision for the wealth of political society.

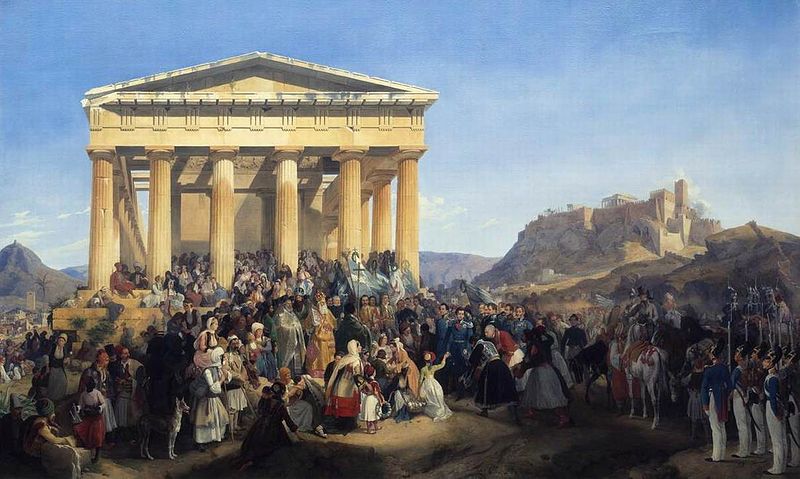

The imminent bicentenary of the Greek revolution of 1821 has been generating a series of scholarly events and research projects in recent years. What would you consider to be the main stakes in Greek historiography regarding this period?

The bicentenaries of other revolutions in places such France, the States, or Haiti generated a wealth of scholarship that changed the historiographical scene. I hope we do the same, not least because the Greek revolution is surprisingly underexplored. It is not the place to say why this is so. But you are right that many things seem to come up. The question is to use the occasion productively and not for show off. In my opinion, there is one key aspect that we need to take into account when studying the revolution: that it was part and parcel of the Age of Revolutions. With some very important exceptions, historical scholarship on the revolution has failed to take this into account and incorporate the Greek case within recent scholarship that has reassessed the Age of Revolutions in important and novel ways.We need to address the absence of Greece in these discussions. We need to start discussing with scholars of other cases and to give back to the revolution its edge. The good news is that the pre-conditions for research are surprisingly good in terms of sources. In fact, these are being made more and more available to researchers and the public in novel ways. A good case in point is the ‘Digital Archive of 1821’, organized by the Research Center for the Humanities. But what is at stake is to exploit these pre-conditions, do research and communicate it as far as possible both within academia and the general public.

*Interview by Dimitris Gkintidis

D.G.

TAGS: HISTORY | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | RESEARCH