Artemis Leontis is C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek and Comparative Literature and chair of the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan. Her field of specialization is Modern Greek Studies and her research interests range from the study of Greeks and the Greek language to the idea of Greece cultivated in the West in the modern period. Her latest book, Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2019), tells the story of an atypical American philhellene, while at the same time addressing larger issues such as the modern reception of Classical Greece and the challenges posed to the West by Modern Greece. Greek News Agenda* had the opportunity to interview Professor Leontis on her recent research on the life of Eva Palmer Sikelianos, as well as on the present and future of Modern Greek Studies in American academia.

Your recent monograph, Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins (PUP, 2019) depicts the life and work of this atypical American in Greece. How did her vision of Greece differ from established foreign and native views at the time?

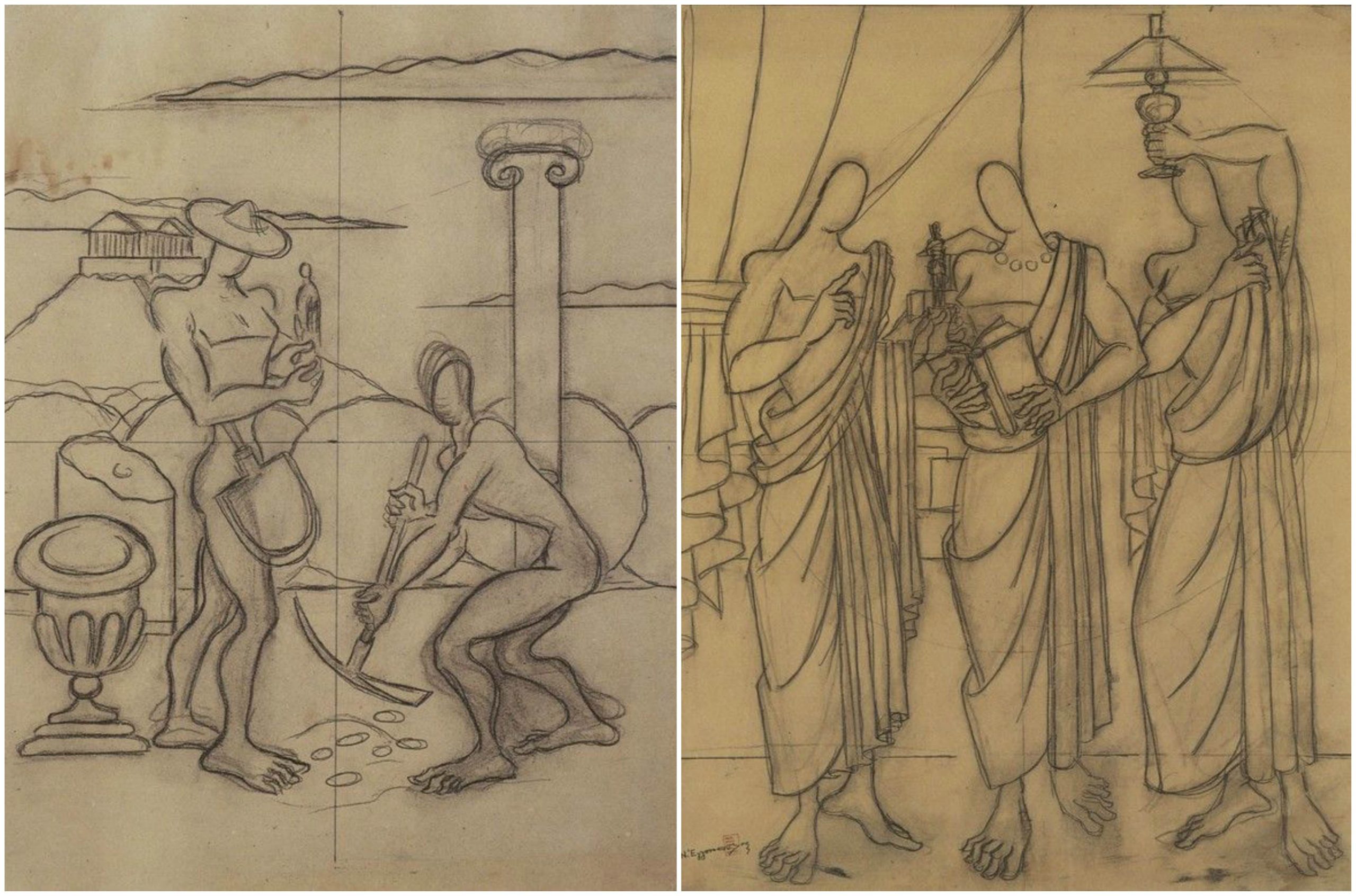

Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952) was a countercultural figure. A New York debutante, she studied ancient Greek and Latin briefly at Bryn Mawr College but left school to pursue an unconventional artistic life. She became a crucial member of the lesbian circle of Natalie Clifford Barney, then moved to Greece and married Angelos Sikelianos. She studied weaving among village women, became proficient in modern Greek, and achieved the status of “master of Byzantine music.” She planned an international school of non-Western school with Khorshed Naoroji, a Parsi woman from Bombay who later joined Gandhi’s non-violent revolution, then abandoned this plan to produce the Delphic Festivals with Sikelianos. In her direction of Prometheus Bound, she brought together techniques from all her previous pursuits. Now, deeply in debt, she returned to U.S. to make a living by directing theater; but the Great Depression followed by World War II limited her prospects. Impoverished and struggling to put a roof over her head, she followed international politics obsessively in the 1940s with an eye to identifying the sources of political repression in Greece. She wrote over two thousand letters to American newspaper editors and politicians supporting democratic forces against the “imperialist tangle” of British and American interests. In 1951, now blacklisted for her criticism of American imperialism, she was denied a visa to travel to Greece in the “Return to Greece” European Recovery Plan. A few weeks before her death, she did manage to return to Greece and was given the funeral of a national hero.

Though classicizing in her interweaving of the Greeks with every aspect of her life, her vision does not align either with established foreign viewpoints, which typically see Greece as an archive of the past, or with Greek views that claim elements of the Greek past as native traditions. I would call it an “in-between,” or “queer” in the fullest sense viewpoint: it problematizes not only gender and sexuality but also nationality, class, politics, and temporality in ways that do not fall neatly into categories.

What I find truly fascinating and actually quite current is her restless striving to realize herself by making herself different: by running against history’s course to reach an impossible transcendent untimeliness.

In what sense does your biographical study of Eva Palmer Sikelianos address larger social issues?

The book addresses the erasure of women, particularly queer women, and other marginal groups from history. This is a major social issue. Patriarchy and homophobia are major social problems. As a cultural biography of Eva Palmer Sikelianos drawing on the abundant, diverse, and richly layered archives of modern receptions of Greco-Roman antiquity, it brings special attention to the kind of systematic erasure of women, gays and lesbians, and other undervalued users of the Greek past from the archive of Greek learning.

Eva Palmer Sikelianos has been strangely invisible in cultural history, even though she is a crucial link connecting the search for new identities and artistic forms in the early twentieth century with classical learning. In Greece, where she is known as Sikelianos’s wife and helper, her story was censored in order to promote a particular legacy of Angelos Sikelianos. Sikelianos actually wrote her out of his account of the making of the Delphic Festivals, and his literary executor, Anna Sikelianos, worked to make inaccessible the sources of Eva Sikelianos’s life that revealed the scope of her polyamorous attachments with women. After her death, people covered over her political opposition to the monarchy. Her work was fitted to the procrustean bed of patriarchal, nationalist, and heteronormative discourses.

This kind of systematic erasure is a matter of social concern because it has shaped the stories we tell ourselves in ways that short circuit our understandings of how things came to be and what they are. For example, the erasure of the transnational, gender queer aspects in the staging of the Delphic Festivals contributed to a Greek national reading of the events. By this I mean that diverse performance aspects developed through her wide range of collaborations have been ignored: from her work on lesbian theatricals to her collaboration with Konstantinos Psachos and intense dialogue with Khorshed Naoroji. This huge oversight has for years given free rein to Greek national interpretations of the popular aesthetic derived from the festivals.

Case studies such as Eva Palmer Sikelianos draw attention to nonspecialist users of ancient sources who turned to Greek antiquity to imagine their social alterity. Moreover, we recognize the contribution of these undervalued creators to cycles of renewal that revise old codes of interpretation to make Greek sources relevant to new generations.

Your work on Eva Palmer Sikelianos reminds us of the inevitable weight of classical heritage on the imagination of modern Greece—on academia included. In what ways can the discipline of Modern Greek Studies negotiate this ambivalent relationship?

I can address the academic side of your question. From the time when Modern Greek Studies emerged as a field in the early 1970s in the U.S., it has been negotiating its relationship with the field of Classics. This has been an institutional matter, since many Modern Greek programs are located in Classics departments; it is also an ongoing, dynamic intellectual concern.

The first Modern Greek programs were housed in Classics departments for an odd assortment of reasons: because a faculty member happened to know modern Greek; graduate students working in Greece wished to learn to communicate in the language; no other modern language department presented itself as a better home; etc. To bridge the disciplinary gap, the first-generation of scholars drew connections of recent Greek literary works with the classical heritage. They pointed to the persistence of good writing from Homer to Cavafy, Sikelianos, Seferis, and Elytis—some of the poets they singled out for their powerful self-expression against the background of a weighty literary inheritance.

A decade later, scholars studying contemporary Greece from a broader set of disciplines took a more critical, nuanced stance on the relationship of Greece with the past. Many works stand out: Ours Once More(1982), Michael Herzfeld’s account of the emergence of folklore in nineteenth-century Greece, mapping out the intertwined perspectives of newly liberated Greeks and Westerners who expected them to prove their ancient ancestry; Vassilis Lambropoulos’s Literature as National Institution(1988) identifying the nation building aspects of Modern Greek literature; Stathis Gourgouris in Dream Nation (1996) advancing the argument that Greece functioned figuratively both as an alibi for the cultural ideal of colonialist Europe, and as an unpredictable institution unraveling the certainty of European history. My first book, Topographies of Hellenism (1995) on the contrapuntal relationship of foreigners’ projections of their idea of Greece on the Greek landscape and Greek literary modernist’s reterritorializations of them, was part of this project.

I bring these up as examples of the kind of politically conscious scholarship appearing in Modern Greek Studies in the 1980s and 1990s that identified the classical as part of the self-figuration of the West and represented contemporary Greece as a living, changing context within which the classical has been continuously reworked and reimagined. With respect to Classical studies, scholars in Modern Greek studies were trendsetters in their insistence on paying attention to the contexts in which the cultural construct of a classical heritage gained its enduring power and versatility.

In important ways, Modern Greek Studies functioned as a precursor to Classical Reception Studies, the subfield of Classics emerging in the late 1990s that studies the contexts in which the texts, materials, and ideas of Greece and Rome have been received and reimagined. At the University of Michigan, the endowment in 1999 of the C. P. Cavafy Professorship in Modern Greek contributed to the creation of “Contexts for Classics,” the interdisciplinary faculty consortium that explores the reception of classical antiquity. Modern Greek Studies thus became a crucial voice making Classics aware of the critical importance of context and ideology.

Today, the classical and its legacies in the West are under scrutiny as never before. As Chair of the Department of Classical Studies, I am seeing the most concerted effort from within the Classical studies to dismantle the Eurocentrism of the field. It is an unfortunate sign of the lingering power imbalances handicapping Greece, however, that only a few classicists—Joanna Hanink stands out—point to the ways that idealized classical imagery is deployed to denigrate Greeks still today.

Meanwhile Modern Greek studies programs institutionally located in Classics departments continue to grow in numbers, with the University of Illinois at Champagne-Urbana, UCLA, and UC Santa Barbara announcing the most recent new hires. This puts scholars of Modern Greek in a position of responsibility as never before. We must continue to bring attention to the ideological construction of a classical heritage that excluded people living in supposedly classical lands. This work requires allying ourselves with scholars in other fields and working side by side with them to dismantle exclusive claims of ownership of the past.

What would you consider to be the main developments in the study of Modern Greece, and how do these communicate with more general trends in the Humanities?

I’ve already referred to several major developments: studies that pay attention to gender and sexuality; work that is comparative and crosses national lines; critical, politically engaged work on heritage. Once upon a time, we studied Modern Greek figures and sources in isolation. Now our view of Greece has become transcultural, transnational, and comparative. I’ve also talked about the shifting relationship of Modern Greek studies within Classics, which speaks to the more general trend to foster diversity in the Humanities by dismantling old hierarchies of power. These are all developments in Modern Greek studies that communicate with more general trends.

Another very exciting trend is the relatively new field of Modern Greek archaeology. This is a form of historical archaeology dealing with material sources for which there are written records and oral histories that help to contextualize them. Susan Sutton was a pioneer as an anthropologist working on the Nemea Project. Yannis Hamilakis’s archival and material excavation of the concentration camps on Makronissos was groundbreaking. Kostis Kourelis’s trans-Atlantic Deserted Greek Villages project moving between abandoned Greek villages and immigrant neighborhoods in Philadelphia is truly innovative. Some students of Classical archaeology have begun to draw lessons from these projects to apply their methods to interface more directly with surrounding communities in Greece and other countries where they work.

In undergraduate education, we have been introducing new pedagogies in language instruction, including classroom technologies that bring students in contact with their peers in Greece. Translation has reappeared in language classes at an advanced intermediate level to help students build linguistic and cultural knowledge and appreciate the challenges of intercultural literacy. These connect with trends in the Humanities that highlight evolving pedagogies and recognize the dynamic and omnipresent role of translation in a globalized world where translators are active participants bearing ethical responsibility in geopolitical conflicts. These and other pedagogical innovations place Modern Greek studies at the cutting edge of efforts in the Humanities to train students not just as learners but as culturally literate citizens in a global world.

The heavy emphasis on the relationship between Greece and “the West” is a recurrent theme in works pertaining to Modern Greece. Would you consider that this runs the risk of recasting structural asymmetries into “cultural difference”?

It depends on how precisely the work addresses the relationship of Greece and the West. Let’s take the example of English-language articles on Greece’s relationship to Europe during the debt crisis. These have tended to do exactly what you say: posit Greece’s fundamental cultural difference from the West to make claims that Greece does not belong as an equal partner in the West. In this case, cultural difference is part of the discursive practice of the West that creates structural asymmetries by stereotyping and degrading, and so justifying actions that subjugate them. A complement to this is cultural work that asserts something exceptional and fundamentally non-Western about Greece. The latter is a strategy of setting Greeks apart that partakes in the same discursive practice separating the West from the rest even as it tries to overturn structural asymmetries.

The scholarly strategy that matters today differentiates itself from the preceding by actually highlighting structural asymmetries in the relationship of Greece in the West. It addresses questions of power and analyzes the complex set of ideas and images that have made ancient Greece a cornerstone of the West while marginalizing contemporary Greece. By analyzing how the West, in its execution of power, asserts its superiority in the world, and how Greeks adapt notions of themselves borrowed from the West in ways that sometimes overturn them—this strategy has the opposite effect. It recasts cultural difference to bring to light the kinds of structural asymmetries that have been haunting Modern Greece since its inception.

You were recently appointed C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan. What are the new initiatives planned from your new position?

Two prevailing conditions mark my taking this position. One is the status of Modern Greek studies at the University of Michigan. For the past twenty years, I have been part of the development of full-fledged Modern Greek Program offering a major and minor in Modern Greek and PhD opportunities in many departments. Under the leadership of Vassilis Lambropoulos, with the crucial contribution of Despina Margomenou, we have taught thousands of undergraduates, granted nearly 200 degrees, supervised honors theses and prize winning PhDs work, placed and supported students in internships and jobs, hosted hundreds of events featuring scholars from across the world, organized exhibits, built a substantial library collection, and communicated by way of our program’s website with the broader community worldwide. The position of the C P. Cavafy Professorship is endowed. This is a beautiful, strong, wide-ranging program.

The second condition is the canonical status of C. P. Cavafy. When Michigan named the endowed professorship in Modern Greek after Cavafy, he was already the best known poet in Modern Greek. I curated the exhibit “Cavafy’s World” with Lauren E. Talalay in 2002, and hundreds of people attended the opening. We extended the exhibit several months to accommodate visitors. Our companion book “‘What these Ithakas mean…’: Readings in Cavafy,” went through its first run quickly. The Times Literary Supplement listed it as one of the best books of the year. Our work was good, but its reception also showed that Cavafy has a central place in the universe of writers.

In this environment, my strategy is not to duplicate what has already been accomplished but to work selectively for maximum impact. Modern Greek studies at Michigan will remain at the cutting edge through attention to pedagogies, curriculum, and support of scholarly and artistic exchange. Regarding Cavafy’s work, I will continue to publish new work on the Cavafy Forum, a platform on our program’s Modern Greek website supporting debates, bibliographies, scholarly commentary, and creative work. For example, last fall I published “Greek Necropolis,” a poem by Peter Jeffreys accompanied by his essay, “The Greek Necropolis at Norwood.” I’ve just learned that the publication has inspired a campaign to restore he monuments of West Norwood. Next will be a bibliography of the substantial body of musical compositions and songs responding to Cavafy’s poetry.

Cavafy is canonical, as I said before, and so I consider it my responsibility also to bring attention to forgotten or undiscovered work. Of older authors, who has been overlooked and is crying out for translation? Of contemporary artists, who should be supported? Here are two initiatives:

One is to offer short visiting residencies by emerging scholars and artists, including poets, writers, translators, musicians, and visual and performing artists from Greece. I began this work in 2016 with the invitation of Cacao Rocks and Olga Alexopoulou, artists in residence at the Institute for the Humanities. These are made possible by a recent gift from Kathleen L. Vakalo, wife of the late Emmanuel George Vakalo, professor of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan, and daughter-in-law of artist George Vakalo and poet Eleni Vakalo. The Vakalo name is known throughout Greece for the wide range of contributions to the arts, education and cultural activism. I want to open the door for young people from Greece with worthy projects to make use of the resources of this university and inspire and be inspired through dialogue with faculty and students.

My second planned initiative is to create and edit an active Anglophone book series for exciting interdisciplinary work in Modern Greek Studies with the University of Michigan Press. Nothing analogous to this exists, even though there is marvelous work in line to be published. I saw some of this work during my five years as the Humanities editor of the Journal of Modern Greek Studies. I am hopeful that this will happen, and if it does, I think it can be a game-changing project.

*Interview by Dimitris Gkintidis

D.G.

TAGS: ARTS | EDUCATION | HISTORY | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | LGBTI | LITERATURE & BOOKS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | WOMEN & GENDER