Professor Roderick Beaton grew up in Edinburgh where he first studied Latin and ancient Greek before going on to Peterhouse, Cambridge, to graduate with a BA in English Literature and a PhD in Modern Greek. He came to King’s in 1981 as Lecturer in Modern Greek Language and Literature, and in 1988 was appointed to the Koraes Chair. For ten years he headed the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies (whose functions since 2015 have been taken over by the Department of Classics), and from 2012 to 2016 was Director of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, part of the Arts & Humanities Research Institute.

From October 2009 to September 2012 he held a Major Leverhulme Fellowship, and during autumn 2010 the Visiting Fellowship of the British School at Athens (BSA), on whose Council he also serves. His book Byron’s War: Romantic Rebellion, Greek Revolution (2013) won the Runciman Award and the Elma Dangerfield Prize and was shortlisted for the Duff Cooper Prize. In 2013 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy (FBA).

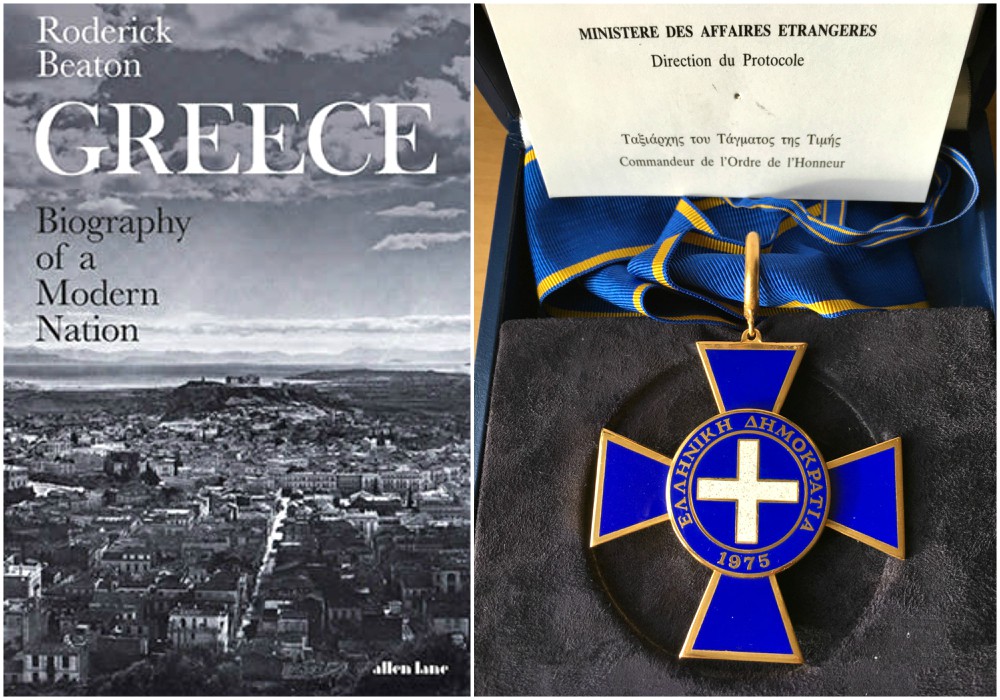

Professor Beaton published his new book Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation, in March 2019.The book sets out to understand modern Greeks on their own terms, revealing how a modern nation was built on the ruins of a vanished ancient civilisation. Beaton chronicles the last 300 years of the Greek nation-state, covering its political conflict, financial crises and vibrant culture, to demonstrate Greece’s “evolving process of collective identity”.

The Financial Times included the volume in their list for best history books of 2019, writing that it “deserves to be the standard general history of modern Greece in English for years to come” and it “captures the full dimensions of Greece’s recent troubles“; Professor Gonda Van Steen, Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King’s College London and Director of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, also commended the publication as a “bold new look on an ever-evolving topic, modern Greek history, delivered by a scholar eminently qualified to address it”.

On 9 September 2019, Professor Beaton was awarded the Medal of the Commander of the Order of Honour, bestowed by HE the President of the Hellenic Republic Prokopis Pavlopoulos, in a special award ceremony held at the presidential mansion, where Pavlopoulos praised Professor Beaton for his exceptional contributions to the study of the formation of Greek national consciousness. In November 2019 he was also included in the “Greece 2021” Committee, responsible for the celebration of the Bicentennial of the Greek War of Independence.

On 9 September 2019, Professor Beaton was awarded the Medal of the Commander of the Order of Honour, bestowed by HE the President of the Hellenic Republic Prokopis Pavlopoulos, in a special award ceremony held at the presidential mansion, where Pavlopoulos praised Professor Beaton for his exceptional contributions to the study of the formation of Greek national consciousness. In November 2019 he was also included in the “Greece 2021” Committee, responsible for the celebration of the Bicentennial of the Greek War of Independence.

Professor Roderick Beaton spoke to the Press & Communications Office at the Embassy of Greece in London regarding his publications, his interest in Greece and its history and his recent his honorary proclamation as Commander of the Order of Honour.

What does the award of the Medal of the Commander of the Order of Honour by HE the President of the Hellenic Republic mean to you as a person and as an academic? What does this honorary distinction mean also for the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature, Centre for Hellenic Studies, King’s College, which you presided over for many years? How do you believe this honour may impact Modern Greek studies in UK’s universities?

It’s the greatest honour of my life! The President was very generous in his citation when he conferred the award, and mentioned several of the books I’ve published over the years, about Greek literature, culture and history. But it never occurred to me that anything I was writing would merit such a response on behalf of the Greek state from its very head! And of course, everything I’ve written, all my lectures and my teaching going back 40 years – none of that I could ever have done on my own. So it’s also an honour for the Koraes Chair at King’s College London, for the College itself, as well as for other institutions that have helped me on my way: the universities where I studied (Cambridge) and gained my first experience as an academic (Birmingham) and the British School at Athens, with which I’ve been associated ever since my student days. As for Modern Greek studies in British universities – well, that’s a continuing story. Every support from Greece is welcome. But the future lies with the students (British, Greek, or from whatever country) who will engage with Modern Greek history, language and literature in years to come. And I wish there could be more enthusiastic, or visible, support for studies of this kind in the UK of tomorrow than there seems to be today.

What motivated you to engage with Greece and its history? Has it to do with British scholars’ long-standing deep admiration for the Greek antiquity and acclaimed British universities’ long tradition with classics or was it the result of a personal discovery from your unmediated contact with the country and its people?

You’re quite right – I did start out as an impressionable adolescent fascinated by the classical tradition. But what fascinated me most, right from the beginning, was the fact that I was starting out to learn a language had been spoken and written for the last 3000 years. I was just 13 years old when a family holiday took me to Greece for the very first time. I was bowled over by the sheer vitality of the place, the rugged lines of the landscape, the loudness of the voices, the brightness of the Greek sun. (You should know that I grew up in Edinburgh, sometimes called the “Athens of the North” – but a darker, greyer place, I assure you!) And I fell in love with Greek music, right from the start. I think it was on a jukebox on Mykonos that I first songs that I later realised must have been by Theodorakis. From that time, I was “hooked”. I studied Ancient Greek for 4 years at school, and it was one of my favourite subjects. But I was not cut out to be a classicist. I always wanted to be a writer. I loved books and literature. For my first degree I chose not Classics but English Literature. When I came back to Greece at the end of my undergraduate degree, it was no longer the ancient world I wanted to study, but modern Greece. And I’ve been doing that ever since!

In your recent book Biography of a Modern Nation you suggest that the recent economic crisis, apart from a financial and economic phenomenon, was the result of a number of interconnected factors, including aspects of the nature of Greek identity, the role of the state and the nation’s place in the modern world. Are there recurrent patterns in Greek modern history that are likely to emerge again and generate fresh challenges in the future? Are there also cultural characteristics and social mentalities that play a role too?

In your recent book Biography of a Modern Nation you suggest that the recent economic crisis, apart from a financial and economic phenomenon, was the result of a number of interconnected factors, including aspects of the nature of Greek identity, the role of the state and the nation’s place in the modern world. Are there recurrent patterns in Greek modern history that are likely to emerge again and generate fresh challenges in the future? Are there also cultural characteristics and social mentalities that play a role too?

I still have a lot to learn about the crisis of the last decade, its immediate causes – and of course it’s far too soon to begin to guess what its longer-term effects might prove to be. Talking with Greek friends, and with others who had the opportunity to spend more of the last ten years in Greece than I did, I’m reminded that the distance that enabled me to try to grasp the whole of the country’s modern history in a reasonably short book also has its downside. That said, I found plenty of evidence that the roots of the recent “crisis” can be traced far back into the events of the past and into mentalities that have developed or have been preserved over at least 200 hundred years. To take just a couple of examples, compare the attitudes to taxation at the end of the 1820s and the 1830s, at the time when Capodistrias was “Governor” of Greece and then when the Bavarian Otto was king, and during the PASOK years. Or consider the foreign loans made to Greece during the Revolution and while it was ending. The lifeblood of the fledgling state came in the form of loans, not gifts. The Greek state has struggled ever afterwards to repay those debts – while a different sort of debt, a cultural one this time, from modern Europe to ancient Greece, can surely never be repaid either!

A very famous Greek scholar[1] wrote in one of the most read books in Greece “When a Greek talks about Europe, he automatically excludes Greece. When a foreigner talks about Europe, we [Greeks] consider it unthinkable that he may not include Greece.(…) Who are we? Are we the Europeans of the East or the Orientals of Europe?” Do you have an answer to his questions?

In my book I argue that Greece doesn’t belong to only the West or only the East, but actually to both. “Europe” as a name and as an idea begins with the Greeks, in the pages of Herodotus’ Histories of the 5th century BCE. Europe is unthinkable without Greece, where so much that we think of as European started. But Greece, as the modern country was created and sustained after the 1821 Revolution, in turn forms an integral part of Europe, and therefore of “the West”. On the other hand, Greece is equally the inheritor of the thousand-year-long Byzantine tradition, in which Orthodoxy represents the “Eastern” form of Christianity, as opposed to the Catholic and (later) Protestant West. So there’s no single or simple answer to the question!

Your interest in Greece has been almost exclusively focussed on two main areas: Greece’s history/politics and its literature. Byron and Seferis engaged in both, as both were renowned poets with an active involvement in Greece’s politics. However they lived and acted in a completely different historic period and context and they have contributed in a completely different way to Greece’s modern history. Why have you singled out these historic figures for further study? How is each of them important in Greek history? Do they share common characteristics?

You’re right – I’ve increasingly been attracted to figures who bridge the gap between what we conventionally think of as “literature” or “culture” on the one hand and “history” or “politics” on the other. I think it goes back to my own university education and the earlier stages of my professional career, when these branches of study were rigorously separated (as they still are, at least formally, in Greek universities). I was taught to read poems and novels without much reference to the world in which they had been written or subsequently read. I think it was because I spent so much of my time in Greece during the 1970s that I began to rebel against this. You can’t teach British students about Solomos without also teaching them about the Greek Revolution of the 1820s. Once they begin to read poems by Seferis, there’s so much they also need to know about Greece’s history in the twentieth century. And so it goes on. I believe that studying history enriches the way we read literature. And I also believe that many “traditional” historians have missed out badly, because they’re reluctant to step “over the line” and examine the evidence that works of literature provide for us about the lives and mentalities of people who lived in the past. So yes, Seferis and Byron are completely different from one another – in the time that they lived, in nationality, in temperament. But they have this in common: they were both towering figures in the literature of their respective languages, who also crossed that line and played a part in events that did (even if only a little) changed the world in which they lived, and we do too.

In a recent interview with Kathimerini[2] you said, “What I am particularly pleased about is that Greeks aren’t straying from the centre of the political spectrum: The previous government was centre-left and this one is centre-right. The pendulum swings both ways, but ends up in the centre, unlike in the UK, in the US and even in Italy, where it swings dangerously close to the extremes”. How do you explain this centrism? Has it to do with historical experiences (civil war, junta) or has it to do with a deep rooted in Greek mentality philosophical principle drawn from Aristotle’s idea of “mesotita“?

In a recent interview with Kathimerini[2] you said, “What I am particularly pleased about is that Greeks aren’t straying from the centre of the political spectrum: The previous government was centre-left and this one is centre-right. The pendulum swings both ways, but ends up in the centre, unlike in the UK, in the US and even in Italy, where it swings dangerously close to the extremes”. How do you explain this centrism? Has it to do with historical experiences (civil war, junta) or has it to do with a deep rooted in Greek mentality philosophical principle drawn from Aristotle’s idea of “mesotita“?

I wouldn’t be too confident in attributing modern political attitudes to Aristotle or the ancient maxim about the “golden mean” (Παν μέτρον άριστον)! Greece has suffered from its share of political extremism in its modern history – and let’s not kid ourselves that the ancients were always able to avoid extreme politics either. Aristotle laid down an excellent principle, but historians like Thucydides and Xenophon tell us what actually happened, and it often wasn’t pretty! But my point was about the recent elections in Greece and the simultaneous turn in politics in my own country. Greeks have suffered vastly more than most British people as a consequence of the financial crash of 2007-8 and the possibly mistaken policies of austerity pursued by the European Union afterwards. But it seems to me that Greeks have also learnt from their experiences. Whereas in Britain a substantial minority, egged on by a partisan press, believe that they have been victimised by the European Union when they haven’t, and seek an extreme remedy in Brexit. British politics are more polarised in the last months of 2019 than they have been at any time since the English Civil War of the 1640s. Maybe, after all, more Brits should read Aristotle!

In your Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation you state, “I believe — indeed with a passion — that Greece and the modern history of the Greek nation matter far beyond the bounds of the worldwide Greek community”, and in a recent interview with Kathimerini, you said, “Greece to me is the present and the future. It’s a work in progress”. Could you please elaborate more on these comments? Do you believe that Greece will continue to attract the interest of next generations of historians and –in the affirmative – why?

I often quote Lord Byron, speaking at Missolonghi in 1824, shortly before he died there in the service of the Greek Revolution. He said: “those principles which are now in action in Greece will gradually produce their effect, both here and in other countries. … I cannot … calculate to what a height Greece may rise. Hitherto it has been a subject for the hymns and elegies of fanatics and enthusiasts; but now it will draw the attention of the politician.” What Byron meant, I think, is that the Greek Revolution was to be a testing ground for a whole new kind of politics. The new country would not merely import a political system from somewhere else: European politicians need to learn from the example of Greece, not the other way round. It hasn’t always worked out quite like that. But the potential has always been there. And let’s not forget that Greece, when it was internationally recognised as independent in 1830, became the first of the new nation-states that would transform the European continent from that time to this.

You have argued that Greece represents the “paradigm nation”, the one that, historically speaking, sets the example, because Greece was the first new nation-state to be established anywhere in Europe after the upheavals of the Napoleonic wars, recognised by an international protocol of 1830. All other modern nation-states have followed the example of Greece. Why, in your opinion, this aspect has never been emphasized by European and other historians? How do you believe this could change the perspective of Greece’s understanding and its positioning in the contemporary world? How do you believe Greece could capitalize on this?

To set the record straight, the phrase “paradigm nation” belongs to my colleague at the University of Athens, Emeritus Professor Paschalis Kitromilides. But I have indeed argued for greater recognition to be given to this simple fact of history. I suppose one of the problems is that when nation-states emerged later, elsewhere in Europe, their leaders were not necessarily thinking about what had happened in Greece in the 1820s and 1830s. It wasn’t that Italians, Germans and Poles (say) set out deliberately to do what the Greeks had done before them. But it’s a fact that the Greeks had done it before them, and in that sense they set in motion a process that has been going on ever since. Think of the great “national unifications” in Western Europe in the 1860s: of Germany and Italy. Later, after World War I, came the creation of a whole swathe of new nation-states to replace the Austrian and Ottoman empires. The collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989 had a very similar effect – most devastatingly in the Balkans, where the wars in the former Yugoslavia led to the creation of new independent nation-states, most recently Montenegro in 2006 and Kossovo in 2008. The other reason is down to the way Greeks themselves have told their story, from Zambelios and Paparrigopoulos in the 1850s and 1860s until very recently. By emphasising the revival or regeneration (παλιγγενεσία) of Ancient Greece in the achievement of the modern nation, these historians have detached that achievement from its immediate context in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe and presented the Greek case as unique and exceptional. In fact, most nations build and project their modern identity by drawing on aspects from a more-or-less distant past, so the Greek case isn’t unique at all. More remarkable than Greece’s legacy from antiquity is the achievement of modern Greeks in being the first to build the kind of modern state that is now the norm throughout Europe and much of the rest of the world.

Although classics still attract a considerable number of British and international students wishing to explore the Greek antiquity, Modern Greek studies seem to be in decline in the British Universities and elsewhere in Europe. What are, in your opinion, the causes for this decline and how do you think this could be reversed?

Although classics still attract a considerable number of British and international students wishing to explore the Greek antiquity, Modern Greek studies seem to be in decline in the British Universities and elsewhere in Europe. What are, in your opinion, the causes for this decline and how do you think this could be reversed?

Part of the trouble, at least in Britain, has been the decline of interest in learning foreign languages. This goes back several decades and is the result of a mistaken belief that the rest of the world speaks English. And of course that decline has been made much worse by the rise of “Euroscepticism” and the aftermath of the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union. It’s not just Modern Greek studies that are under threat in the UK – even German is going the same way, and most European languages, other than Spanish and French, have disappeared completely from the curriculum. Paradoxically, it may be that if Britain really does leave the EU and we find ourselves isolated from our nearest neighbours, we might find it useful to begin once again to learn their languages, if only so that we can buy our food from them!

You retired from the position of the Head of the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature, Centre for Hellenic Studies, King’s College London in 2018, but you are still nourishing a keen interest in Greece. What are you currently involved in and what are your plans for the future?

I’ve always thought of myself as a writer, and retirement from the university has given me the opportunity to devote myself to writing full-time. I once published a novel, and who knows, I might yet publish more! In the meantime, my next book will be not about Greece but… the Greeks.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Roderick Beaton on the bicentenary of the Greek War of Independence; Rethinking Greece: Roderick Beaton on the study of Greece and modern Greek achievements; 100 years from the founding of the Koraes Chair at King’s College, London ; Reading Greece | Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek

[1]Nikos Dimou, “On the Unhappiness of Being Greek”, 2013

[2]Kathimerini, 14.9.2019

TAGS: HISTORY | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | LITERATURE & BOOKS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES