Antonis Chaldeos is a historian, writer and Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg. His research focuses on the history of the Greek Diaspora in Africa. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Johannesburg, has published several articles in peer-reviewed journals, as well as 10 books on the Greek presence in Africa, including: The Greeks in Morocco during 1904-2012; The Greek presence in Tunisia (16th-21st century); The Greek presence in Mozambique; The Greek community in Sudan (19th-21st) century; The Greeks in the horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia); The Greek community in Tanzania; The Greek community in South Africa; The Greek community in Malawi, and more. He maintains an active blog, Greeks of Africa as well a Facebook page by the same name where he publishes excerpts of his research.

In 2017, he was honored with the St. Marcos Holy Cross by the Patriarchate of Alexandria and All of Africa for his contribution to the promotion of the Hellenism in Africa.

Antonis Chaldeos spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the political and economic circumstances that resulted in the Greek presence in Africa, the Greeks’ contribution to the host countries and relations to the local population, their activities in agriculture, construction, trade and industry, the unknown history of Greek communities in Sudan and Mozambique and Ethiopia, and finally, on the future of the Greeks in Africa.

What were the political and economic circumstances that resulted in the Greek presence Africa? Are there any distinct (geographical, chronological or other) trends to Greek migration in Africa, like for example to North Africa as compared to sub-Saharan Africa?

Greek presence in countries that were also part of the Ottoman Empire, such as Tunisia and Libya, dates back to the 16th century. As far as sub-Saharan countries are concerned, Greek immigration started during last quarter of the 19th century, as a result of the political and social conditions in the wider south-eastern Mediterranean area, and the strategy of the European colonial powers in Africa. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the duration of the journey from Europe to Asia decreased and new ports were founded to refuel the ships making this journey. Gradually these ports became the starting points for exploration into the unknown, but rich in natural resources, Africa.

It was the period of intensified competition between European countries for the exploitation of Africa that created the background and the conditions for the migration and settlement of European citizens in that Continent. In addition, the need for infrastructure, both to move European military forces in a continent where the landscape was covered by desert, jungle and large rivers, and to open up trade routes, led to a high demand for a skilled workforce. Finally, we should note the key role of the introduction of steamships, which facilitated long-distance migration, especially for the Greek islanders.

The majority of the Greek immigrants in Africa settled in urban centers as they were more attractive locations for those who wanted after a relatively short time of work to return to Greece or invest their money in a small business. Most of them were involved in trade. However, in Eastern Africa, a significant number of Greeks engaged in agriculture and livestock development that were strenuous activities with low prestige and uncertain profit.

In Kenya, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, Nyasaland and Mozambique, many Greeks had farms and livestock. They took advantage of the lack of interest of the political and economic elite that avoided dealing with the difficult, demanding and less profitable agriculture sector. Greeks dealt with the intensification of the existing crops and introduced new ones, such as tobacco. They were pioneers, they invested money, and they laid the foundations of the industrialization in many countries such as Sudan, Mozambique and Zambia.

Greeks know a lot about the Greek community in Egypt, but no so much about the Greek presence in other African countries. In which other country (or countries) would you say the Greek community had a particularly significant contribution?

Between the late 19th and the early 20th century, Greeks gradually emigrated to more than 25 countries throughout Africa. Although they were not numerous in most of the countries where they settled in, their role in the local economy and society was decisive. Greeks had a fundamental role in the history of Sudan till the 1880, were responsible for the industrialisation of Mozambique in the 1940s, dominated agriculture sector in Tanzania and Malawi and controlled coffee trade in the horn of Africa.

The Greeks who settled in Sudan during the 19th century were widely dispersed within this huge country -the third biggest in Africa, settling even in the most desolated areas, when no other European had ever been. In the first decade of the 20th century the number of the Greeks living in Sudan grew steadily as there was a strong demand for work force. That time, almost 2,500 Greeks resided in Sudan while the total number of the Europeans including the British colonial administration was 3,100 people. Due to the construction fever that Khartoum experienced between 1899 and 1902, thousands of workers arrived in the capital of Sudan. Most of them were of Greek origin. Gradually, more Greeks settled in the city making the Greek community the largest among the Europeans of the Sudanese capital.

Apart from being the most populous European community, Greeks proved to be protagonists in Sudanese economic history. The majority of Greeks turned to trade, both import and export. Those who were export-oriented bought raw materials from the domestic market and distributed them primarily to big trading houses that had office branches inside or outside Sudan. A typical case of a Greek tradesman was G. Contomichalos, owner of the largest import-export firm in Sudan that also participated in numerous international businesses ventures.

Some Greeks went into the construction sector, making the most of Sudan’s burgeoning development and the effort to build land and maritime infrastructure. In the late 19th century, Greeks became also involved in the industry sector and established the first factories in Omdurman and Khartoum in tobacco, flour mills, oil, sesame oil and cottonseed oil.

The Greeks of Sudan focused their professional activity on two main categories throughout the 20th century, trade and constructions. However, few of them owned coffee shops and restaurants. Typical is the case of “Great Britain” that belonged to Panagiotis Pagoulatos. It included a restaurant, pastry shop and bar. Gradually, it evolved into one of the largest bars of Khartoum.

As mentioned before, the Greeks were pioneers in the industrialization of Mozambique, investing money and laying the foundations for new industries. The Greeks’ role was also in fundamental in the constructions sector, as they took up one of the biggest transport projects in south eastern Africa, the building of a bridge in lower Zambezi which linked Malawi with Mozambique in the 1930s. The Greeks’ industrial activities in Mozambique were focused on tobacco, food processing (milk, juices) and plastics.

Greeks who immigrated to Ethiopia in the late 19th century implemented a wide range of infrastructure works in Addis Ababa and other cities. Those who dealt extensively with trade managed to overcome difficulties -such as increased mortality due diseases and extreme geophysical conditions- in order to provide even the most remote regions of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia with products.

Lots of Greeks marked the history of host countries. Two examples that stand out in my mind are, firstly, George Stravelakis, an enslaved Greek who as a child survived the massacre of Chios in 1822, to be sold as a slave and raised by the family of the local Bey in Tunis. There he was converted to Islam and was given the name Mustapha. He managed to climb to the highest offices of the Tunisian state: he became state Treasurer (Khaznadar), lieutenant-general of the army, Bey in 1840 and finally to president of the Grand Council from 1862 to 1878.

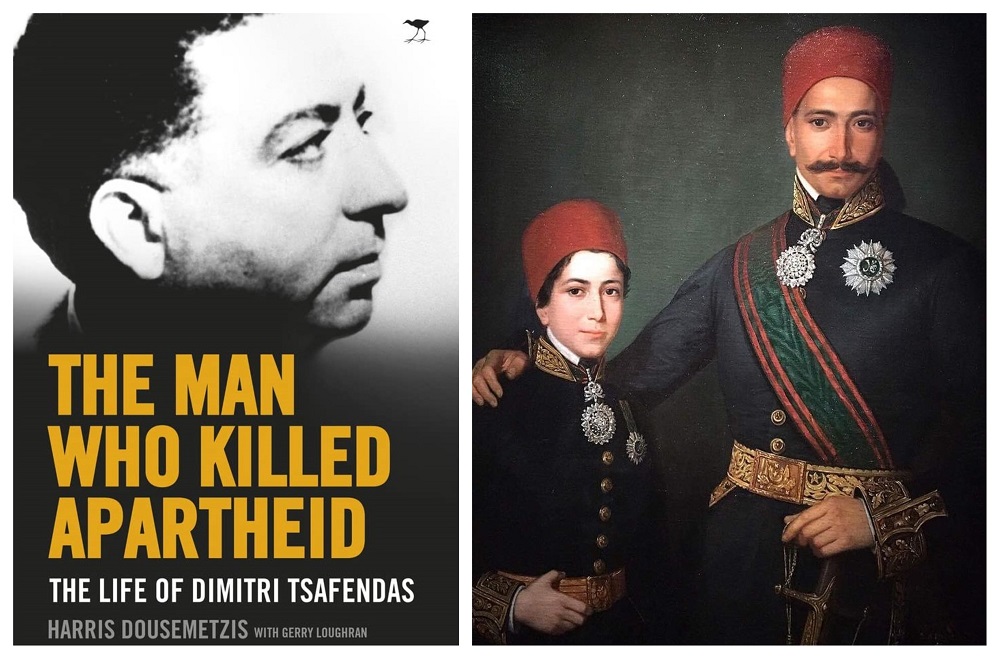

The story of Dimitris Tsafendas, the man who in 1966 assassinated the South African prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd -commonly known as the architect of Apartheid- is also fascinating. Dimitris Tsafendas was born in Mozambique, Lourenço Marques in 1918.His father, Michael Tsafendis had emigrated from Crete in 1915 and his mother was Amelia Williams, a Mozambican of mixed race. In his adolescence, Tsafendas worked as a labourer in South Africa, where he was organized in the Communist Party due to his political beliefs and also because no other political party (including the African National Congress) accepted people of mixed race.

In 1957, Tsafendas participated in the unarmed demonstration of 20,000 black South Africans in the town of Sharpeville, a few kilometers outside of Johannesburg, where 20 police officers killed 69 people and wounded 830, including Tsafendas himself. According to the Apartheid laws, he was a mulatto and as a result, he had difficulties finding a job; also he was also unable to marry the woman of his choice, because Apartheid laws did not allow marriages between people of different race.

In July 1966, Tsafendas found a temporary job as a messenger in the Parliament of South Africa. On September of the same year, he assassinated the prime minister of South Africa Hendrik Verwoerd, who died three days later. The trial started lasted four days and Tsafendas refused the defense lawyer, declaring “I did my duty. Kill me”. Initially, the judges condemned him to death. Nevertheless, to avoid political ramifications, the judges changed their initial verdict and declared him not guilty by reason of insanity. Tsafendas was sentenced to life imprisonment and transferred to a high-security prison in Pretoria where he was tortured.

He died in 1999 and the Greek community of Krugersdorp covered the cost of his funeral. He was buried without a gravestone, only with a stone with the number J59 inscribed on it, the number he had as a prisoner.

Tsafendas had became a symbol of the struggle against the apartheid, and in the great demonstration of 1976 in Johannesburg, people chanted rhythmically “Tsafendas inyanga yezizwe” (Tsafendas liberated the nation). However, he passed into oblivion soon after the end of apartheid. Recently, interest in his life has been rekindled and his memory as a hero of the anti-Apartheid is being restored.

The range of the professional activities of the Greeks community, as they have been shaped over the years, defined the social status of the Greek community. From the mid-19th century, the majority of the Greeks who settled in Africa were farmers, merchants, railway workers and people without professional experience. Migration was considered a one-way street due to the economic and social pressures for personal and family survival in Greece. From the 1930s, the identity of the Greek migrant changes, as a significant number of educated and experienced Greeks came from Asia Minor, the islands of the Aegean and Cyprus to settle in Africa. Many Greeks have shown great determination and managed to advance to a higher social status. After 1930, a small group of Greek settlers had evolved into industrialists, owners of large estates and building contractors acquiring wealth and fame.

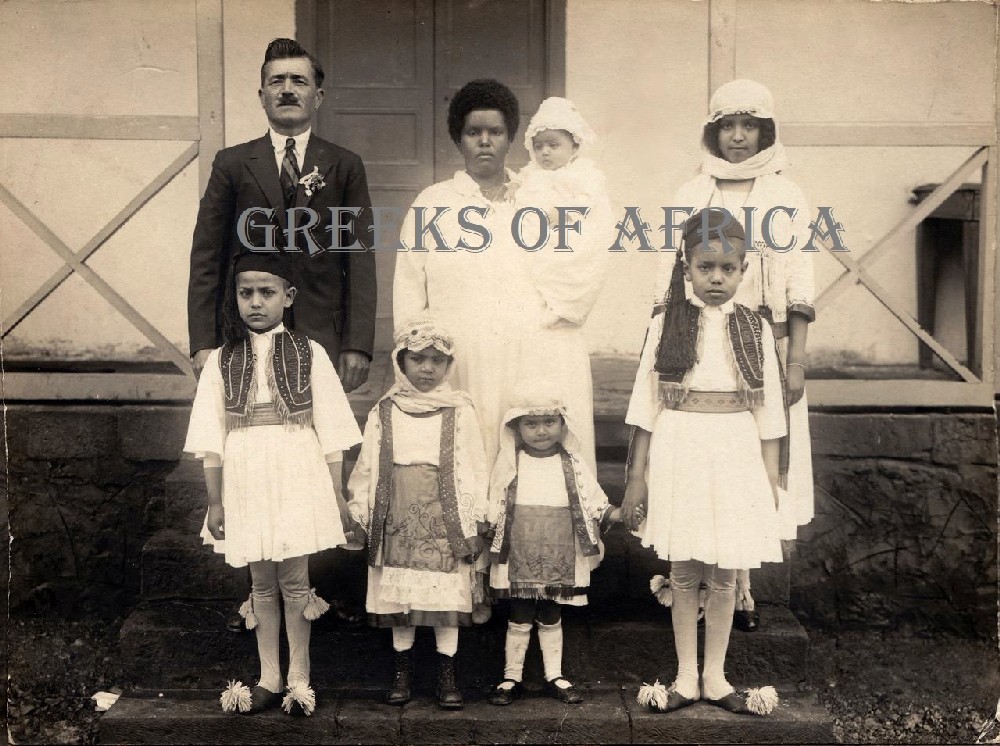

Although Greeks were among the first Europeans who settled in Africa in the 19th century, they were considered as second-class Europeans. As Greeks experienced a kind of marginalization, they chose deliberate isolation from the colonial elite. This attitude was also derived from their need to preserve their ethnic identity within a multicultural society: Greek communities, until the first quarter of the 20th century were characterized by introversion and endogamy. The first migrants, who were usually men, after their first decade in Africa visited Greece and married spouses from their place of origin. Of course, at this point it should be noted that some Greeks from the late 19th century to the first two decades of the 20th century have established marriages with local women.

What were the relations like between the immigrant Greeks and the indigenous people in African host countries? How were they affected by colonialism?

The long-standing presence of the Greeks in Africa has been the reason for creating friendship bonds with the indigenous people of the continent. Greeks treated indigenous Africans as equals. An important factor determining these relationships was the professional activities of the Greeks: from the late 19th century, Greeks’ involvement in trade and agriculture brought them with close and direct contact with the local population; these relationships were favored by the fact that Greeks learned to speak the local languages.

What does the future look like for Greek communities in Africa in a post-colonialist era? Are there any countries were Greek presence is still particularly strong or that it is increasing?

Today, although the official data do not provide us with a very accurate picture, the total number of Greeks living in Africa is estimated at 100,000 people, excluding the descendants of mixed marriages who do not have Greek passports and who resided mostly in Ethiopia, Sudan and South Africa. The majority of the Greeks live in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Congo and Nigeria. However, in the last few years, the Greek communities in Africa experience are slowly increasing again, as a result of the crisis that plagued Greece.

In particular, Greeks who used to live in Africa and returned home in the 1980s or 1990s have, due to the difficulties in finding work in Greece, re-emigrated to several African countries and either invested money in their compatriots’ businesses or started their own activity as entrepreneurs. As a result, the Greek presence in some countries such as Nigeria, Malawi and Zambia the Greek presence is still strong.

*Interview by: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: DIASPORA | GREECE-AFRICA RELATIONS