Emilia Salvanou is a historian of modern and contemporary History, specialized in issues of memory, migration/refugeehood and historical culture. She studied History at the University of Athens, obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Aegean, and continued with a post-doc at the University of Athens. She has worked in European and Greek research projects, and taught at the University of Thessaloniki and is an an adjuct faculty member at the Hellenic Open University. She has published on issues of memory, migration and forced population movements in academic journals. She is the author of “The making of refugee memory: past as history and practice” (in Greek, Nefeli 2018) – which was recently translated to Turkish – and of “How do we learn history without being taught of it: Historical culture, public history and history education” (in Greek, Asini 2021).

Emilia Salvanou spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the integration of 1,2 million refugees from Asia Minor to Greece during the interwar period as “an excellent example of the synergy of political will, state policies, the implementation of reforms and the active participation of refugees”, but not without difficulties and obstacles; how the refugees strived and succeeded in maintaining their cultural identity; the process through which refugee trauma and lived memory turn into a “cultural memory” for all Greeks; the need to look at the refugee movements of the extensive World War I in their international context, as people fled their homes to escape the violence of war throughout Europe and finally, how this year’s centenary is an opportunity to study the uprooting of Asia Minor Greeks and history of the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922 in its wider historical context, as the end of a historical era and through which the political entities, identities and institutions that we know today, were formed.

About 1,200,000 refugees from Asia Minor arrived in Greece in 1922. Their integration, although not without obstacles and challenges, is largely considered a very successful process. What was the dynamic of the relationship between the state, the natives and the refugees?

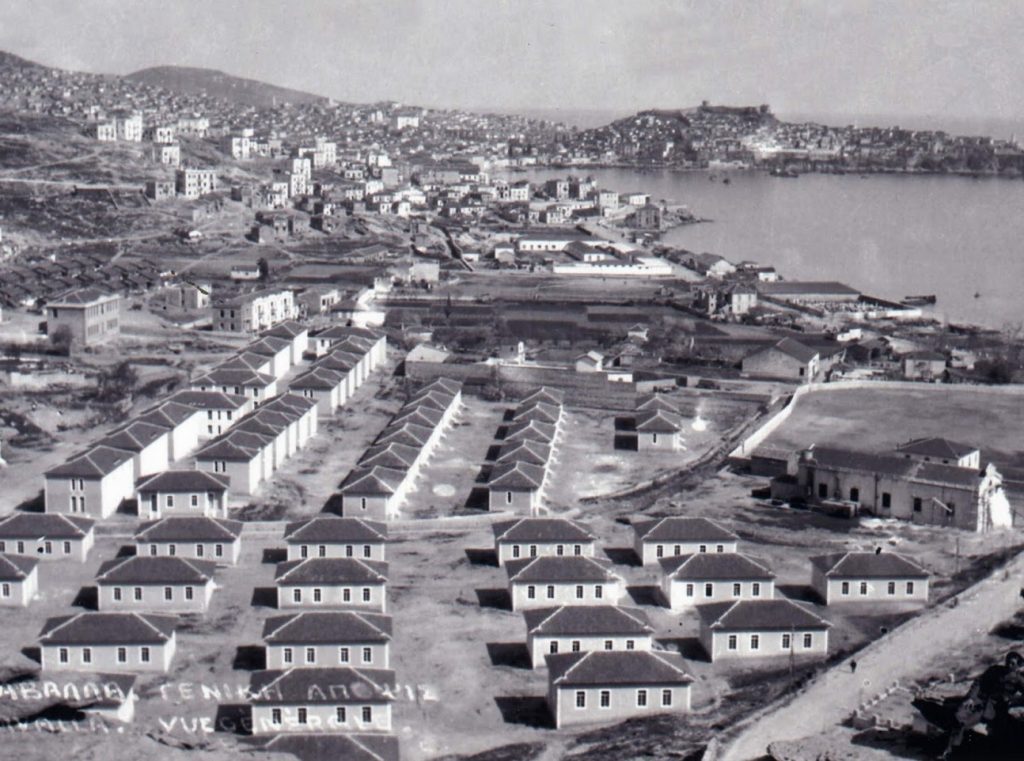

Indeed, the integration of refugees in the interwar period is an excellent example of the synergy of political will, state policies, the implementation of reforms and the active participation of refugees. The challenge came mainly from the size of the refugee population (up to 1/5 of the country’s total population) and from the fact that it was not a temporary phenomenon, but a permanent one. The initial difficulties of the first year were addressed with the help of international humanitarian organizations – the Red Cross, Near East Relief, the League of Nations, and the Refugee Rehabilitation Committee. But very quickly the Greek state had to deal with the situation relying on its own forces.

From the beginning, the state wanted the refugees to be acommodated in the direction of autonomy. Thus, it implemented a series of reforms, some of which matured for a long time, such as the agrarian reform and the decision to expropriate the land and redistribute it, in order to give land to the refugees. At the same time, the state used the refugees to demographically boost the so-called New Lands, especially Macedonia and Thrace, dealing thus with the territorial aspirations of neighboring countries. The other package of reforms launched thanks to the presence of refugees was that on employment, social security and public health – reforms imposed by the demographic change caused by refugees in general, and in the work landscape in particular, changes that eventually transformed Greek society as a whole.

Maintaining a balance was important during this process. The need to integrate the refugees could not fuel the anti-refugee sentiment that already existed within Greek society. It was not uncommon for the masses of refugees to evoke feelings of distrust and competition, especially among the working classes of the native population, as the overabundance of the labor force posed a real risk of falling wages. Thus, the need to preserve the social peace is often present in the rationale of the reforms – sometimes even explicitly.

Finally, the refugees themselves became actively involved in the process of their rehabilitation and integration, appointing their political representatives and participating in practices that facilitated their integration into the national imaginary. But we will talk about these issues later.

However, the process seems successful from above and from the outside; from the perception of the state. If we look at the experience of the refugees themselves, things appear very different. These people were uprooted, they lost their community-organized world, and they blamed state policies for that. After all, many spoke of harmonious relations with the neighboring peoples while in Asia Minor, before national ideologies and wars cultivated intolerance and violence. Besides, the refugees’ experience was not just one of uprooting. The transition from displacement to rehabilitation was not automatic – and often proved to be just as traumatic. Many suffered having to move from place to place when they we living Asia Minor, and then had to do the same again in Greece. And all of this was happening against a background of violence, the aversion of the locals, diseases and loss. It is no coincidence that the term “refugee sorrow” prevailed: sorrow refers not only to what is left behind, but also to their suffering in the new situation. After all, if the settlement had been so successful, the refugees would not have turned to the Left, nor would they have filled the ranks of the National Liberation Front during the Nazi Occupation. The refugee identity was forged not only from the experience of uprooting, but also from what it meant to be a refugee in Greece – and the corresponding practices they developed to cope.

Maintaining their identity was one of the biggest concerns of the refugees, at least in terms of those who were in a somewhat better social and economic position and had the comfort of dealing with issues that went beyond those of daily survival and the immediate consequences of uprooting. These were mostly Greeks from Asia Minor that had already settled in Greece before the wave of refugees that arrived in the country during the turbulent years of the First World War, and mainly after the collapse of the Greek front in the Greek-Turkish war of 1919-1922 and the decision of compulsory exchange of populations. These Greeks from Asia Minor had pursued distinguished careers in science, politics and culture. When the uprooting took place, they acted as “mediators of memory.” So what did they do? Although the refugees had to face distrust from the locals, distrust that often amounted to what we today would call social racism, their political rights were secure. Since the refugees had been granted Greek citizenship, it was believed that sooner or later, they would be integrated into Greek society and the initial reactions of the locals would be surmounted through coexistence. Indeed, as the years passed, refugees and locals had to face together social, political and national challenges, culminating in the Occupation and the Resistance, the old dividing lines faded, giving way to new ones. What preoccupied the aforementioned “intellectual” refugees during the interwar period, was whether this integration would lead to assimilation – and that was the point at which they chose to intervene.

Why not assimilation? Identity retention is paramount to building resilience in new environments. This can be seen in the modern refugee and immigrant communities, which come together around religion, language, the preservation of morals and customs, immigration associations, and even insist on wearing the traditional dresses of their homeland. And all this even true for people who had a much more relaxed relationship with tradition before leaving their place of origin. Many times this resilience in the refugees has to do with the adversities they face. The nostalgia refugees and migrants feel is not just about wanting to return. It is often an emotional process that allows the processing of the past, the preservation of identity in new circumstances, the invention of ways of adapting to the new situation without losing oneself.

The refugees from Asia Minor who acted as mediators of memory, all of them with a prominent social position, pioneered the establishment of associations that functioned as reference points for the uprooted refugees. On a second level, however, these associations set the tone for integration and laid the foundations for the formation of the refugee memory. The largest of these associations, and those that, if you will, managed to secure political and social support from the Greek state, became involved in magazine publishing. Already in their very first issues of these magazines a clear concern was expressed, that cultural identity should not be sacrificed at the altar of integration, and that these magazines were to function as “memory arcs”.

The refugees’ past was “translated” through the magazines in a way that was recognizable by established national memory, reflecting in fact some of its main historical junctures. Articles published in these magazines made use of archeology, history and the folklore studies to highlight the continuity of Greek presence in Asia Minor, from antiquity to Byzantium and from the existence Greek communities of the Ottoman Empire to the modern era.

Hellenism in Asia Minor and refugee experience are now fundamental elements of historical memory in Greece. How did the refugee trauma turn into a “a site of memory” for all Greeks? How was Greekness redefined after the end of Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922?

We are talking about the process through which lived memory becomes cultural memory. The way in which the refugee memory was formed, in harmony and in line with the national memory, to a large extent created the conditions for its general acceptance. When the Greco-Turkish War ended in 1922, the public debate was mainly concerned with the defeat and its causes, as well as the end of the policy of national expansion (“Megali Idea”). The refugee experience was not part of the debate. When the refugees occupied the public discourse, it was mainly in the context of their need for rehabilitation. They were treated as the “refugee problem”, which mean the refugees were defined by factors external to them. Light was shed on the refugee experience only gradually and initially at the margins of the relevant discourse. I am referring here to the three ways through which the refugee experience was illuminated the first years after 1922: the recording of the cultural traditions of refugees by Melpo Logotheti-Merlier (work that later became the basis for the establishment of the Center for Asia Minor Studies, the capturing of the uprooting and refugee experience by literature and refugee magazines -in the latter case, highlighting the refugee past and refugees themselves as active social subjects rather than talking only about experience of uprooting.

The fact that the refugee experience became visible, gradually contributed to opening up space for receiving the relevant memory. Here we start with two facts: one was that a relevant experience already existed, due to the previous expansions of the Greek state. Every time the borders changed, new areas were integrated along with their past, with the notion of Greekness expanding to include them in the national narrative – no longer abstractly, but with the materiality of the monuments, the customs and traditions, the local history, of the local idioms etc. Secondly, the Greekness of Asia Minor had already been cultivated as an ideology and the request for the areas integration into the Greek state has been prepared already from the beginning of the 20th century, if not from the end of the 19th century. The problem was not ideological, but the shock that came from the defeat (it was no longer about integrating areas, but about managing defeat and integrating the uprooted) and from the encounter with cultural diversity. This meeting had already embarrassed the consuls who were sent to Asia Minor and met a different picture than what they had imagined. So what needed to be done was to make it common knowledge that this cultural diversity that the native Greeks encountered was an aspect of Greekness that they were not familiar with – just as had happened with previous state expansions. Only this time they would no longer talk about “New Lands”, but about “Lost Homelands”.

The great opening of Greek society to the refugees took place in the 1960s, on the occasion of the celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922. We usually attribute this ‘opening’ to the way events of the time, such as the Burning of Smyrna were described in Dido Sotiriou‘s novels, for example, or to the approaches explaining how European expansionist policies contributed to Greece’s defeat, or to the fact that the Left played a prominent role in organizing the commemoration of that anniversary. Apart from these, there were additional factors that helped shape a different narrative. In the 1960s there was a general shift towards the history of ordinary people, towards memory, and the study of how great events affected everyday people’s lives. During the same time, for example, the researchers of the Center for Asia Minor were collecting testimonies, and refugee memory, which had been schematically formed in the previous period by journals, took on flesh and blood from the voices of ordinary people and became familiar. And besides, time had past: The experience of the turbulent 1940s had faded previous dividing lines, the first generation of refugees was growing old and slowly passing the baton on to the second, and the reality of social integration allowed for the memory of uprooting and the initial hardships of settling to be narrated from a distance. Furthermore, it allowed to be narrated as part of a common national memory. To this, the role of cultural production was pivotal: the fact that memory was at this point was not any more communicated only by stories shared within the refugee community, but through literature, songs, anniversaries, newspapers, etc. to much wider population groups, meant that it was slowly transformed into cultural memory that was relevant not only to the refugees, but to the nation. It was only a decade later, at the early 1970s, that the narrative of how the refugees contributed to the development of the Greek economy had been consolidated.

From the mid-1970s and especially from the 1980s onwards, the tone of memory changed. Until then, the relevant memory had an epic tone: it spoke of the titanic work of the state that managed to accommodate so many refugees and of the decisive contribution that refugees made to economic development, as they managed to overcome the initial difficulties and get ahead in life. That was just one side. At neighborhoods and at the villages there was another side to the story. At local celebrating holy patron saint of the “lost” hometown or village, the refugees from that place who were scattered throughout Greece, gathered together and remembered again. They danced, sung, and cultivated memory. It then turned it into what is called in a history a traumatic memory, organized around the concepts of trauma and genocide. Of course, there was a trauma before this period, but then it emerged as its pre-eminent component – the component that colors it in. This turn echoed the country’s political climate, with the Macedonian issue becoming prominent the late 1980s and the reception of the first refugees from the Balkans and the former USSR. But there was also a broader shift in cultural and historical studies towards traumatic memory, especially in historical settings where other outlets and visions for the future seemed to have disappeared. This new memory for the refugees and for 1922 imposed a regime of truth about the past, dictated the context through which it should be approached and received institutional recognition in Parliament. It was transformed into a political memory, framed by political rituals and as one of the central junctures of national memory.

In your book you suggest that we should look at 1922 the presence of refugees in the context of the large population movements that marked the whole of Europe at the end of World War I. Can you tell us more about that?

Indeed, this need to broaden the horizons of World War I and its aftermath is increasingly recognized by historians studying the period. The issue has been highlighted by the discussions that have taken place with regard to the hundred years of the First World War internationally. From these discussions it seemed that it is not accurate to define the First World War in the narrow boundaries of 1914-1918. There were wars that should be considered a prelude to it, such as -in our region- the Balkan Wars, as well as wars that the First World War itself produced, such as the Russian and Finnish civil wars, the Irish War of Independence, and the wars between Poland and Lithuania, between Poland and Ukraine, between the USSR and Estonia and between Latvia and the USSR. These wars include the Greek-Turkish war of 1919-1922.

The same goes for refugees. During and immediately after World War I, the reality of people fleeing their homes to escape the violence of war haunted Europe. Belgians fled to France, the Netherlands and England (1914-1915), Serbs to Corfu, Corsica and Tunisia (1915), Russians to Central Europe, the Balkans and Africa after the October Revolution, Armenians to the Middle East and Russia, Jews from Galicia and Bukovina of Eastern Europe to Vienna, Bohemia and Moravia (1914-1915) and so forth. An entire geography of Jewish settlements and cities was lost, especially in Eastern Europe, where the collapse of historic empires also meant the loss of space that allowed multinational societies. The total number of refugees during that time is estimated at around 13,000,000. For each of the communities forced to be displaced, the refugee experience has been registered as a trauma and as being unique – a national exception.

Your latest book deals with issues of historical culture and public history. What opportunities can this year’ centenary since the end of the Greco-Turkish war give us to reflect on our past?

This year’s centenary is an opportunity to see the history of the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922 in its historical context. We are used to approaching it self-referentially, through the lens of the Greek exception. But it was not so. An estimated thirteen million people were deported during the wars of the second decade of the 20th century. Many lost their lives along the way, and most never managed to return to their homes, paying the price for the dismantling Europe’s historic empires and the re-organization of the world into nation-states. Seeing the persecution, the expatriation and the resettlement of refugees from Asia Minor from this perspective does not detract from the drama of uprooting. On the contrary, it helps to understand it in its historical context, as a process that accompanied the end of a historical era and through which the political entities, identities and institutions that we know today, were formed. This also applies to Muslim refugees that were moved from the Balkans to Turkey; they did not have the opportunity to cultivate their memory. Now they are very interested, which is why my book has been translated into Turkish.

Another perspective, emerging from the recent pandemic experience, is to look at its non-strictly war aspects. Forced relocation, overcrowding at intermediate stations and camps, poor sanitation and nutrition, exacerbated the epidemics that anyway plagued people in those years. The Spanish flu, cholera, smallpox, typhoid, tuberculosis and malaria were just some of the diseases that refugees faced. How were they treated? What reforms were caused by them? How, for example, is the establishment of an autonomous Ministry of Health, public health policies and major infrastructure projects, such as drainage and modernization of water and sewerage systems, related to the emergence of a public health discourse after the great demographic change caused by the influx of refugees?

Finally, and returning to the issue of the need to move away from the perception that 1922 was a Greek exception, while commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the uprooting, it is impossible to ignore that the same places are now receiving new refugees. The press of the time and the testimonies of the refugees leave no doubt that then, as today, there was intense moral panic, anti-refugee discourse as well as instrumentalization of the refugees. Nor, of course, does it leave any question as to how traumatic their incarceration in all kinds of closed reception centers, mainly decontamination centers, was, often for months, before they were allowed to start their lives in the new place. Here we need to approach history in an exemplary way, looking not only for what happened, but how the experience of then converses with the experience of now. But mainly, to think whether the vindication of traumatic memory is possible only through the treatment of the corresponding trauma in the present.

*Interview and translation to English by: Ioulia Livaditi