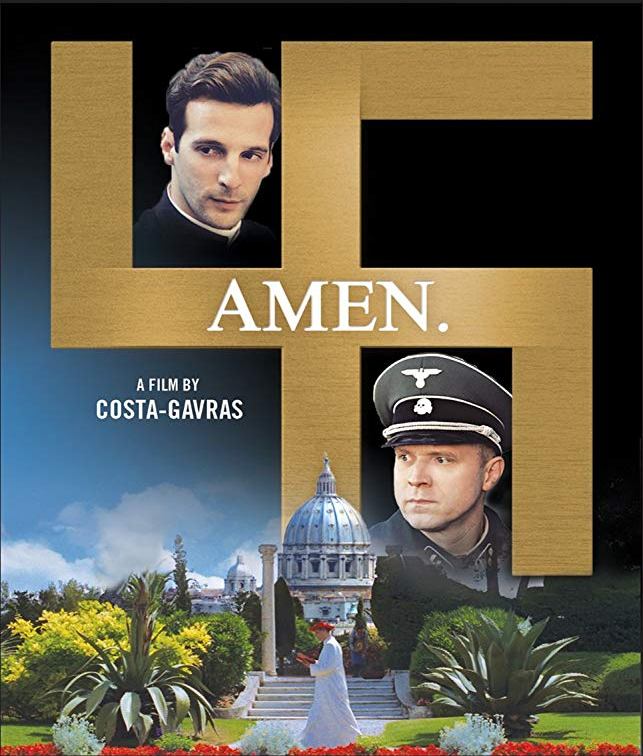

Kostas Gavras was born in 1933 in Loutra Iraias, Arcadia. Following his graduation from high school he went to France, where he did film studies at the French national film school, IDHEC. Following work on several films as assistant director, he directed his first feature film, Compartiment Tueurs, in 1965. His 1969 film “Z”, a fictionalized account of the events surrounding the assassination of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. This was followed by a series of successful films such as L’Aveu (The Confession, 1970), State of Siege (1972), and Missing(1982), which won an Oscar for Best Screenplay Adaptation and the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. His 1989 film Music Box, another film inspired by real events, won the Golden Bear at the 40th Berlin International Film Festival. His more recent films are “Amen” (2002), “Le Couperet” (2005), “Eden is West” (2009) and “The Capital” (2012). Further to his acclaimed directorial career, Gavras is also President of the Cinémathèque Française and founder of the Gan Foundation.

While shooting his latest film, “Adults in the Room”, Kostas Gavras was interviewed by Greek News Agenda and its sister publication Grece Hebdo*. Gavras stressed that what he is mostly interested in his work is a person’s place in society and interaction with power and authority. In his long experience as an internationally acclaimed film director and producer, Gavras elaborates on what constitutes a successful national cinema policy, stressing the need for robust and consistent support from the state. Talking about his experience on filming in Greece, Gavras stresses the positive impact of the new incentives for investments in audiovisual productions in Greece, while he refutes the view that there are no experienced film crews in Greece.

Yves Montand, “Z” (1969)

You have been described as a political filmmaker. Do you think that this description successfully summarizes your work?

This characterization is one by journalists, it is not my problem. I think that the arts in general and not only cinema have a political function in society – not in an ideological sense, but as in influencing our social behavior. Aristotle has famously said that man is a political animal. Why a political animal? First of all, an animal lives in the company of other animals in a group, like human beings. The difference between animals and human beings is that animals only decide about themselves, while humans try to form societies and face difficulties together. Thus, that’s politics for me: what we do in our daily lives and how we interact with power and authority. For me, politics is everywhere; it’s not only about political parties and elections, which is of course a very important part of politics. My films are about our place in society and how we use power. I think that all films are political, even comedies, because they offer us pleasurable moments. A moment of pleasure is important in our life, as long as it’s not vulgar and degrading.

Jack Lemmon, Sissy Spacek, “Missing” (1982)

In your recently published autobiography“Va où il est impossible d’aller” (“Go where it’s impossible to go”) you describe how you left Greece on account of your family’s political history. Which of your films reflects most that period of your life?

My father was labeled a communist, when he was actually only against the monarchy. He had fought in Asia Minor, he saw many of his friends losing their lives, and because he was against the reinstatement of King George at the end of WWII, he was accused of being a communist and repeatedly thrown into jail. He had fought in the Greek resistance with EAM (National Liberation Front) but he didn’t belong to the Communist Party and he didn’t take part in the Greek Civil War. During that period, I wouldn’t have been able to study at a Greek University. The best way for me to study was to escape abroad; as was the case in Greece in 2010, when thousands of young people fled the country. Many went to Australia, others left for the US. I went to France, because it was the only country where I didn’t have to pay fees for my studies. My parents had no money to send me, so I had to work to finance myself.

As far as where this period of my life is reflected in my films, I think that in each of my films there is a part of me as a young man who has lived this kind of adventure. This experience has definitely influenced my work and my choice of films, at both a conscious and subconscious level.

Yves Montand, “The Confession” (1970)

You have worked in France, Greece and the US. In which country and which period did you feel you had more artistic liberty?

I’ve always felt this freedom in France, because the system facilitates those who want to make films. Following the end of the German Occupation in France, a period during which French Cinema was in the hands of the Nazis, all American production of the previous five years entered the French film market and almost wiped out French cinema. The de Gaulle government decided that France had to have national cinema and all subsequent governments continued on the same path, finding solutions to every problem that arose. The advent of television was a threat for French cinema but the state had an answer for that as well. The National Film Centre (CNC) would always find solutions and French cinema enjoys freedom and state support. And support does not only mean money; I’ll give you an example. We filmmakers asked television stations to stop screening films on Saturday nights, because they used to air American blockbusters in that time slot. Now there are no films on TV Saturday night and people go out, view films in cinemas or go to restaurants, instead of watching American blockbusters on TV, as was the case before. We also requested for films not to be interrupted by TV commercials, and only one big channel inserts one commercial break. These facilitations help French film production. That is why 200 French films are produced every year, 30 of which are by first-timedirectors. There are also 30 to 40 films by women filmmakers, which is also unique in the world.

Jessica Lange, Armin Mueller-Stahl, “Music Box” (1989)

Ancient Greek tragedy is recurrent in your films. Your heroes are confronted with Power and Authority in its various forms and they either lose or their victories are hollow. What is the meaning of tragedy for you?

Greece is the birth place of drama. Ancient Greeks introduced tragedy ex novo as a genre and structure. All spectacles in the world follow the rules of Ancient Greek tragedy and follow the same structure as it was defined by Aristotle, having a beginning, middle and end. From the moment we are born, we live with tragedy. The tragedy of life, the tragedy of Greece, which has gone through so many tragedies…then we come to tragedy in drama. For me tragedy is similar to life. Life comprises everything. I don’t really understand those who say we should always be happy. What does happiness mean? We are able to relish happiness, because it’s not something that we enjoy every day. The contrast between happy and unhappy moments in life makes instances of happiness or unhappiness more intense.

And what about power? Has the meaning of power changed in recent years?

We live under authority since childhood; do this, or don’t do that … Power can be positively used, when it is followed by reasoning why something should be done or not. The worst form of exertion of authority for me is when there is no explanation as to why and how. We are endlessly under authority but we also exert authority on other people. This is, as I said before, everyday politics.

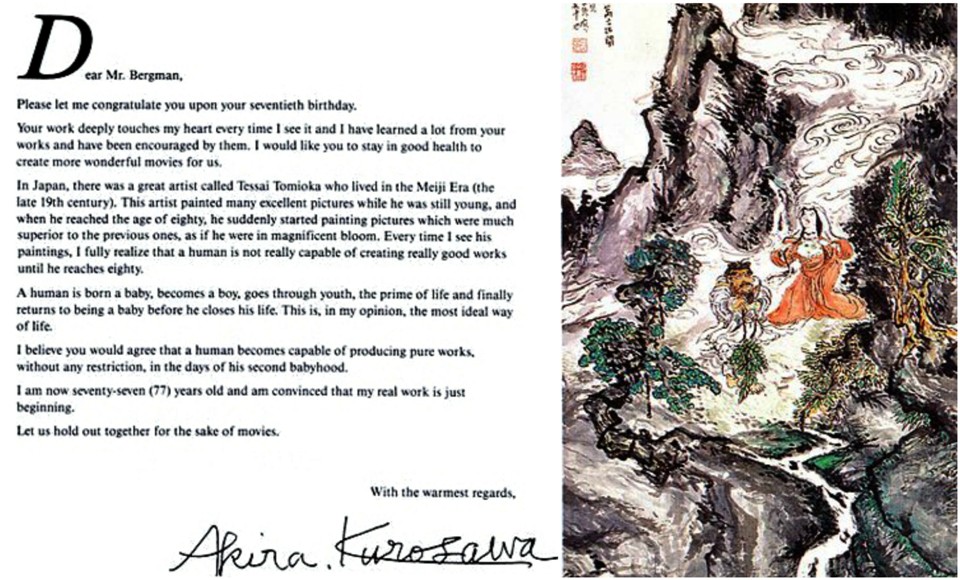

In his letter to Igmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa claims that artists reach their creative peak after the age of 80. How do you feel about that?

I don’t know… it is true that Kurosawa kept making films after he reached 80, but there are certain prerequisites for this, including good physical condition, because film making is like running the Marathon. I myself I’m 86 and I can tell that what changes with age is experience, the way you look at other people and the way you see life. If physical health and experience coexist, then you can expect things. And Kurosawa had both.

Gad Elmaleh, Gabriel Byrne, “The Capital” (2012)

Do you follow developments in Greek cinema?

Yes, I do. At times the state helps cinema, at others it doesn’t. Greek filmmakers feel abandoned. It is not enough to have a National Film Centre; constant help and resolve to support Greek Cinema is necessary, because a Greek film can travel the world and say so many things about Greece. It is imperative to have national cinema with solid and continuous state support and the right legal framework: Greek film makers should be facilitated to shoot in Greek archaeological sites; the Greek Film Centre should enable even “difficult” productions, which are more demanding for the audience. Time and again audiences exceed our expectations and the state must generate those conditions of freedom and support that encourage scriptwriters and directors to create. Many years ago, a Minister of Tourism asked me what changes are necessary to attract foreign productions. I offered him my thoughts, but nothing happened.

Currently there are radical changes taking place regarding the new financial and tax incentives which I find very positive. It’s important to attract foreign producers, because Greece interests them. I know that from discussions with them. They tell me that things are difficult in Greece. These changes are beginning to make things easier for filmmakers and producers. There has to be an ongoing relationship between the state and the filmmakers. If these changes continue, they will bring vast improvements both for economy in general and for filmmakers themselves.

I have to stress that Greece also has excellent crews and technicians. Working on my new film here in Greece, I work with Greek crews and I am really amazed by the quality of their work. First of all, I’m working with internationally acclaimed Director of Photography, Yiorgos Arvanitis, who has a highly competent crew. The sound unit is also excellent and the same goes for the settings. All of the Greek crews I’m working with speak English; they are always prepared and highly skilled. So, it’s not true that there are no skilled film crews and technicians in Greece.

There are small countries with strong national cinemas, such as Sweden or Israel. If smaller countries can do it, why can’t we?

Mathieu Kassovitz, Ulrich Tukur, “Amen” (2002)

In retrospect, do you think that the Golden Era of European Cinema is over? Are you optimistic about contemporary film production?

Film production today is undergoing revolutionary changes, of which we have only seen a fraction, the digital part. The way we think about films, the way we make films and the way films are viewed are changing. The way films are produced is changing. This cuts both ways; the big companies finance films but they impose great limitations to their distribution, in the sense that films can only be available on TV networks. If this continues, the big companies will get more and more power which will escalate to choosing which films are actually produced and which not. We need to fiercely resist this in Europe. Not the system, because the system exists and, from a certain point of view, it has a positive side, in the sense that it offers people living in areas without access to cinemas the ability to watch films in the comfort of their homes. What is negative is that this system can take control of world cinema production, threatening personal and national cinema. But the system does not care about that; it is only interested in the box office. They think they have the recipe for commercially successful films, and this will have bad repercussions on film making.

The notion of National as well as European Cinema must be strongly supported. We frequently appeal to J.-C. Juncker about the actions and steps that need to taken in this direction. Cinema is part of the grand path towards peaceful cooperation that the EU is about. By saying we need to have European cinema I am thinking in terms of financing and a legal framework, because cinema is firstly personal, national and can later become European. Europe must adopt a very positive stance to cinema and we are working a lot in this direction in France.

Would you like to tell us a few things about your work at the Cinémathèque Française?

Would you like to tell us a few things about your work at the Cinémathèque Française?

In the context of film preservation in France, there was an effort to preserve and save silent films (which were never really silent, but this is another issue). Henry Langlois, director of the Cinémathèque, began selecting film and non-film material (scripts etc). Coming to the present, I was asked to become the President of the Cinémathèque with its vast material. We plan to make a European Film Museum and we try to find the necessary funding for that. This project is conducted by the French Cinémathèque but it concerns a European museum, because we have a vast collection in storage which should be exhibited. The young should find out more about cinema history and its educational function in contemporary society. Cinema has helped us come in contact with other cultures, as is the case with Kurosawa, whom you mentioned earlier. When Greek films travel abroad, they inform foreign audiences about the Greek way of life and the Greek way of thinking and this is what makes Greek cinema so important.

Coming back to the purpose of existence of a Cinémathèque, its aim should be to be screening as many films as possible, not only saving them. Every year at the French Cinémathèque we screen about 2.200 films; this means screening four to five films per day. Sometimes we have large audiences, at others we have smaller. That’s what the Cinémathèque is for.

Kostas Gavras interviewed

One last question; are you afraid that home entertainment may substitute cinema screenings?

There is always that risk, but the same has been said about theatre, which is still here after 2.500 years. Cinema is only 120 years old. I believe it will keep on, for the reasons I explained earlier.

* Interview by Florentia Kiortsi (Greek News Agenda) and Kostas Mavroidis (GreceHebdo).

Read also: One more reason to film in Greece: A new legal framework of economic incentives, General Secretariat for Media and Communication boosting Greek Gaming & Animation, Lefteris Kretsos on bringing Greece on the global map of the Game and Film Making Industry.