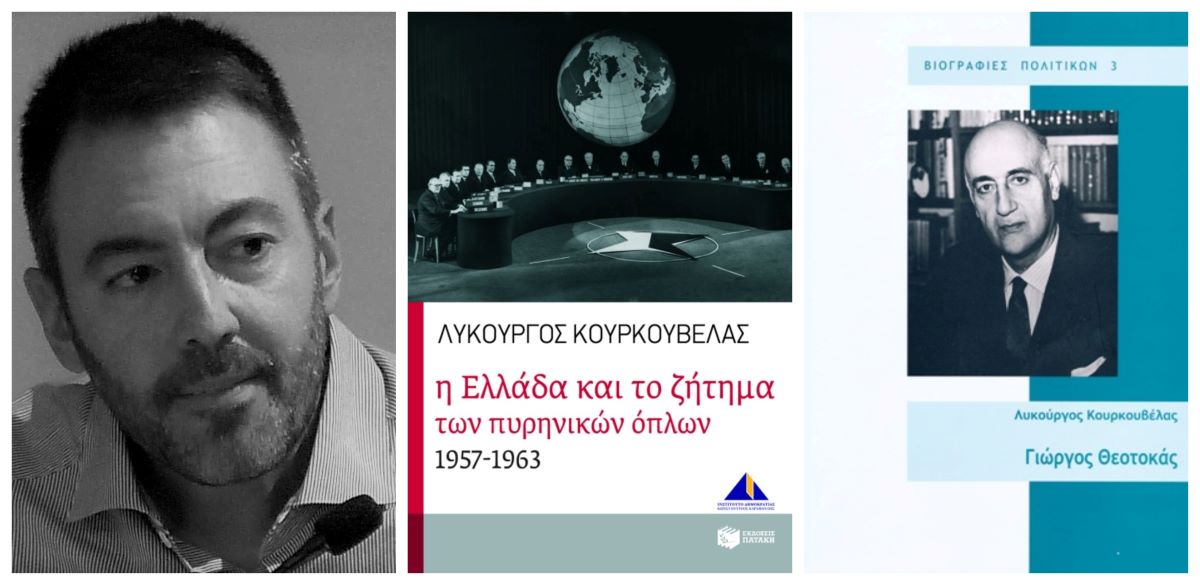

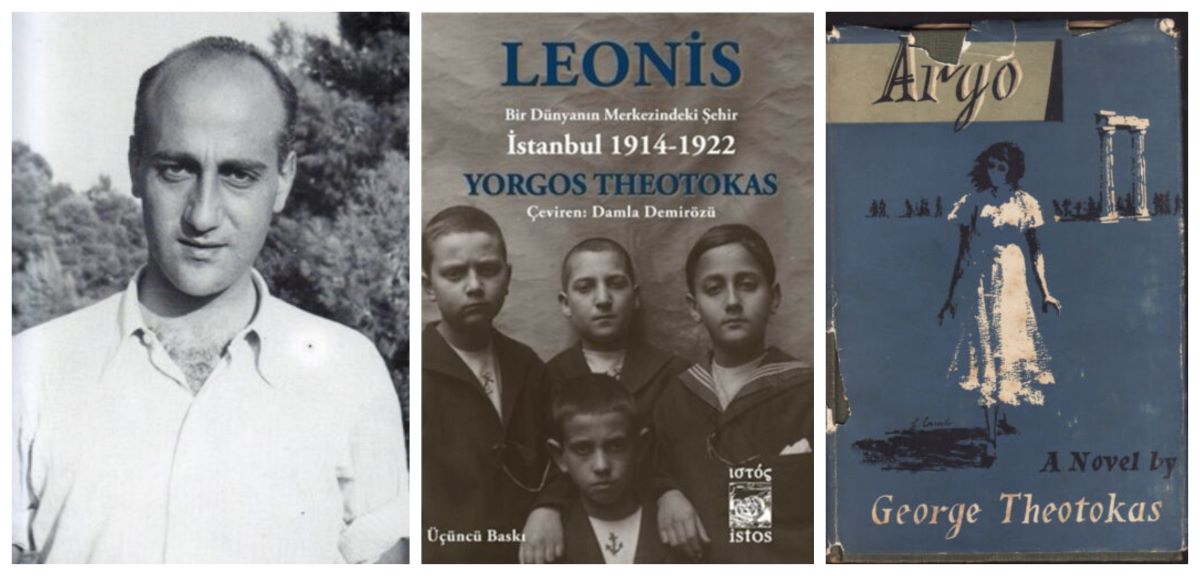

Lykourgos Kourkouvelas is Assistant Professor in the Department of Port Management and Shipping of the School of Economics and Political Science of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. His research interests and publications are on the history of international relations and the cultural Cold War as well as on the history of political and cultural thought in the twentieth century. He has published two books, “Greece and the Issue of Nuclear Weapons, 1957-1963” (2011, in Greek) and “George Theotokas: Political Thinker” (2014, in Greek) which was nominated for the Literature Award of the Greek State. He has published extensively in Greek and English-speaking academic journals and has participated in various academic conferences.

Lykourgos Kourkouvelas spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the cultural and political importance of “Generation of the 30s”, how public intellectuals from the 1930s to the 1960s understood Greek identity, its relation to Europe and to the prospect of a united Europe; antiquity and/or the Orthodox tradition as constituent elements of “Hellenism”; Georgios Theotokas’s endeavor to define Greek national identity and its relation to European culture, his support of the project of a unified Europe and Greece’s participation in it, his belief in federal state entities as the way forward, and finally, his conception of “New Humanism” as an answer to the ‘crisis of modernity’.

The question of whether Greece, in cultural and political terms, belongs to the East or to the West has always been a central part of Greek public discourse. How did the public intellectuals of the “30’s generation” tackle this issue? Do their answers still hold?

First, I would like to point out that the concept of a ‘Generation’, and its use as an analytical tool in literary and social sciences is a complicated and contentious issue; however, for the sake of the discussion I will stick to the conventional concept of the ‘Generation of the Thirties’ that all of us understand.

The ‘Generation of the Thirties’ is, apart from its artistic achievements, important for at least two main reasons. The first is that it raised several essential issues that are still of outmost importance today, such as the ‘meaning’ of Greek/Hellenic national identity and its relationship with the outside world and especially Europe, conceptions and perceptions of European/Western modernity and questions regarding political and ideological identities. The second is that because it attained ‘power’ within various institutions of the Greek state and society (positions in government, theater, cinema, prominent newspapers etc.) it could exert its ideological and even political influence, at least until 1967 and the establishment of the Colonels’ Dictatorship. I should stress that, when we talk about these important issues, we should also have in mind the general context of Greek intellectual history in the period 1930-1967 and not narrowly focus on the ‘Generation of the Thirties’. In addition, it should be stressed that the intellectual and political ideas and practices of those people went hand in hand with developments in the Western world, mainly what was taking place in the most important European capitals. Hence, especially for the cultural historian and the historian of ideas, these intellectuals and their oeuvre are indispensable for the study of the Greek and Western/European past.

In political terms, developments and historical contingencies had ‘tied’ Greece decisively to the West, considering that the 1946-49 Civil War was won by the pro-Western forces, and that during the Cold War Years, the country participated in central ‘western’ institutions such as NATO and the EEC/EU. However, as it always happens with intellectuals, things are much more interesting and complicated in cultural terms. The public intellectuals of the 1930s-1960s time period adhered to the concept of “dichotomy” that characterized previous attempts to conceptualize the cultural orientation of the Greek nation (‘Hellenism’).

On the one side, the majority of the ‘Generation of the Thirties’ (Giorgos Seferis, George Theotokas, Ilias Venezis, Angelos Terzakis etc.), were bourgeois Venizelists, who we educated abroad, and were unequivocally of the view that Greek and European cultures shared central cultural features and values, especially in the context of ancient Greek civilization and Christianity. This view gave, more or less, a prominent role to ancient Greece, which directly linked, in their view, Hellenism with European culture. On the other side, there were important and prominent intellectuals such as Photis Kontoglou, Zisimos Lorentzatos and even the early Christos Yanarras, who viewed Hellenism as an utterly distinct civilization, mainly due to the specific characteristics of the Orthodox tradition and its historical course. It is evident that this side considered European modernity, especially the advent of the Enlightenment, as the root of the decline of Hellenism, and called for a return to Orthodox values both as a metaphysical a well as a cultural guidance in the modern world. Of course, this description is extremely schematic and overlooks the variety and heterogeneity of intellectual views on those major issues. Τhe complexity of this heterogeneity has not been researched in its entire thematic and chronological span and, in my opinion, this is one of the important stakes in modern history studies.

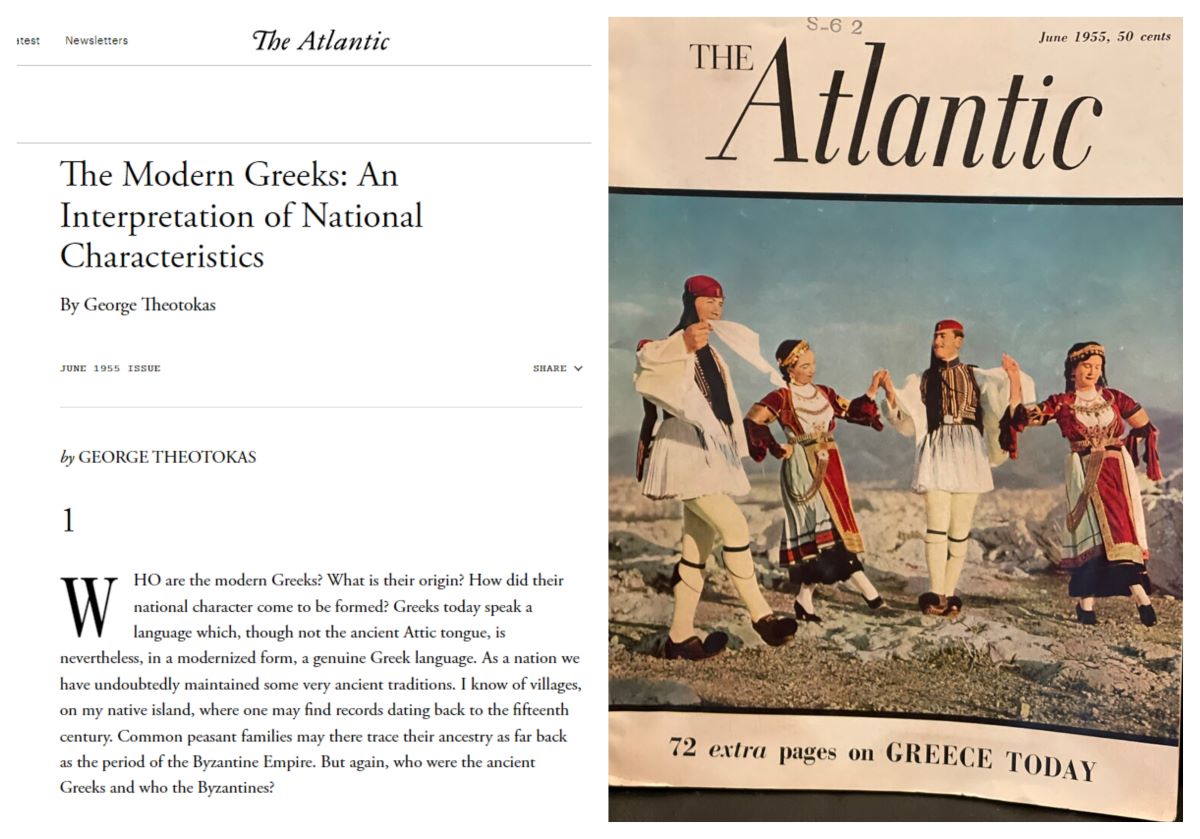

In his article “The Modern Greeks: An Interpretation of National Characteristics” published in the American political magazine “The Atlantic” in 1955, George Theotokas purports that the Greek character is very much shaped by nature; the intensity of the light, the harmony of the landscape, as well as the prevalence of mountains, insularity and the omnipresence of the sea. Would you care to comment?

Throughout his entire intellectual trajectory Theotokas was ‘tormented’ by the idea of the Greek national identity and its relationship with European culture. In different historical periods and at different instances he spoke and wrote of ‘Hellenism’ venturing at finding a ‘solution’ to the problem of conceptualizing the basic features of the Greek national identity. He clearly understood that some kind of a coherent, even if theoretical or conceptual construction of ‘Hellenism’ was necessary in a complex international society that was rapidly moving towards different forms of globalization. He never succeeded. But in his attempts to be as comprehensive as possible, he fluctuated between a cultural and a ‘topological’ conception of “Greekness”. It was an idea that was expressed more clearly and conclusively in the poetry of many of his counterparts such as Odysseas Elytis, Nikos Gkatsos, Yiannis Ritsos etc.

In addition to this ‘topological’ conception Theotokas conceived certain, even, ambiguous or contrasted, features that comprised the idea of Hellenism. Of course, those features were part of his personal value system that was projected in his ‘Hellenism’: ancient Greek moderation, Orthodox Christian metaphysics and cultural values, democratic ideals such as liberty, social justice, political equality, diversity, tolerance and Greek popular culture; all these features found their culmination in important or ‘heroic’ figures or developments of modern Greek history, such as Rigas Feraios, Adamantios Korais, the Constitutions of the 1820s, Makriyiannis, Yiannis Psycharis, Kostis Palamas.

George Theotokas’s article on the “Modern Greeks” was published in the June 1955 issue of the Altantic, which featured a special on Greece, with essays, poems and stories from prominent Greek intellectuals such as Nikos Kazantzakis, Elias Venezis, CP Kavafy, Cosmas Politis, Odysseus Elytis, C. Th. Dimaras, Constantine Tsatsos, Andreas Embirikos, Nikos Engonopoulos, Kostis Palamas, George Seferis, Stratis Myrivilis, Angelos Sikelianos, among others. The full issue is available online.

George Theotokas’s article on the “Modern Greeks” was published in the June 1955 issue of the Altantic, which featured a special on Greece, with essays, poems and stories from prominent Greek intellectuals such as Nikos Kazantzakis, Elias Venezis, CP Kavafy, Cosmas Politis, Odysseus Elytis, C. Th. Dimaras, Constantine Tsatsos, Andreas Embirikos, Nikos Engonopoulos, Kostis Palamas, George Seferis, Stratis Myrivilis, Angelos Sikelianos, among others. The full issue is available online.During the process of Greece’s bid to join the E.U. (European Economic Community, as it was called then), a goal set by prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis as early as 1958, many intellectuals, from the Left and the Right expressed concerns that Greece might lose its separate cultural identity if it became a part of a supra-national organization. How did George Theotokas address these concerns?

Even before the establishment of the modern Greek state, relations with Europe and the West have been characterized by a constant: power relations. Hence, when the Karamanlis government in the end of the 1950s decided to bid for ‘association’ with the newly established European Economic Community (1957) political power and its cultural connotations came, once more, to the fore. We should not forget that even though a large number of the political elite viewed Greek participation in a unified Europe as an ideal, the Greek government and Karamanlis himself, in the context of high Cold War tensions, prioritized political and security needs for Greece’s participation in the European unification bid.

In this context, even many pro-Western/pro-European intellectuals raised concerns for the cultural consequences of Greece’s association (and in the future accession) with the EEC. I speak about pro-Western intellectuals because for the Greek communist Left the EEC was a ‘capitalist club’ of wealthy states that, according to the ‘logic of capitalism’, would necessarily exploit smaller and weaker states and their respective populations. In the case of George Theotokas, concerns culminated publicly in the end of 1958 in the instance of an article that he published in the newspaper To Vima. Konstantinos Dedopoulos and, most importantly, Evangelos Papanoutsos expressed the view that Greece’s integration into a supranational institution that was comprised, compared to Greece, of politically and economically superior European states could have as a consequence the waning, or even the end of Greek national culture.

Theotokas, a staunch supporter of both European unification and Greece’s participation in this development, dealt with this view in two ways. The first was based on a deterministic view of history: due to rapid global economic and technological advancements, history was ‘progressing’ towards large statal entities, in the example of the USA, the USSR and China. For Theotokas, there was only one way for Europe to survive, and that was to follow the example of those ‘continental’ states and, hence, proceed to unification. Accordingly, there was only one way for Greece to survive and that was its participation in the project of European unification. The second way to deal with the concerns that were raised was emotional; Theotokas constantly expressed the view that Greece would retain its most essential cultural features even within a unified Europe, projecting a synthesis between national and supranational identities. The problem is that Theotokas expressed those views axiomatically without dealing with these pressing issues in a systematic/theoretical and rational way. It is that, even if we disregard the specific views that were expressed during this period, questions on the relationship between national and supranational identities remain, albeit in a more complex international context, as pressing today as they were 60 years earlier.

How did George Theotokas and other intellectuals of the “30’s generation” like Konstantinos Tsatsos and Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, with their pro-Europe, pro-West and pro-liberal democracy stance, influence Greek public opinion and/or Greek foreign policy during the Cold War Era?

This is a difficult question because it touches upon an essential epistemological and methodological issue, that of the direct impact of ideas in society and especially in political action. The most obvious answer to that question would be that intellectuals that you are referring to, namely Konstantinos Tsatsos and Panayiotis Kanellopoulos, had also attained political status and power, and therefore their worldviews and ideologies, in one way or another, must have influenced their decisions and actions. For example, we know that Tsatsos played the role of an intellectual ‘mentor’ for Karamanlis, writing his speeches etc. It is also very important that most intellectuals of this generation published articles in everyday or weekly press. To state some obvious examples, Theotokas and Terzakis for To Vima, Aimilios Chourmouzios was Director General of Kathimerini and, to take just an example from the communist Left, Markos Avgeris was a regular columnist in Avgi. Also, there were some important literary journals such as Nea Hestia, Epohes and Epitheorisi Technis.

So the views of the intellectuals were vastly circulated in public sphere; certainly much more than today with the advent of mass society and mass media i.e. television and, most importantly, social media. Still, I have the epistemological view that we can only speculate on the political and social impact of ideas. The best a historian of ideas can do is to place ideas firmly in their respective historical contexts and try to identify the various ways that historical actors ‘used’ ideas in their respective social and historical context. In this way, I stick with the Foucauldian idea of discourse, which he, actually, takes from Nietzsche and his Genealogy of Morality, that views ‘ideas’ as historically shifting clusters of beliefs, values, attitudes and practices that are very often, but not always, embedded in certain practices and institutions.

The horror of the First World War -and later on of the Second World War and the Holocaust- opened up a vivid international debate on the crisis of values in European (and western) modernity. George Theotokas took part in this dialogue with the publication of the essay “Facing a social problem” in 1932, and continued to do so throughout his life. Could you walk us through his concept of “new humanism”, and the role of Hellenism and Orthodox religion?

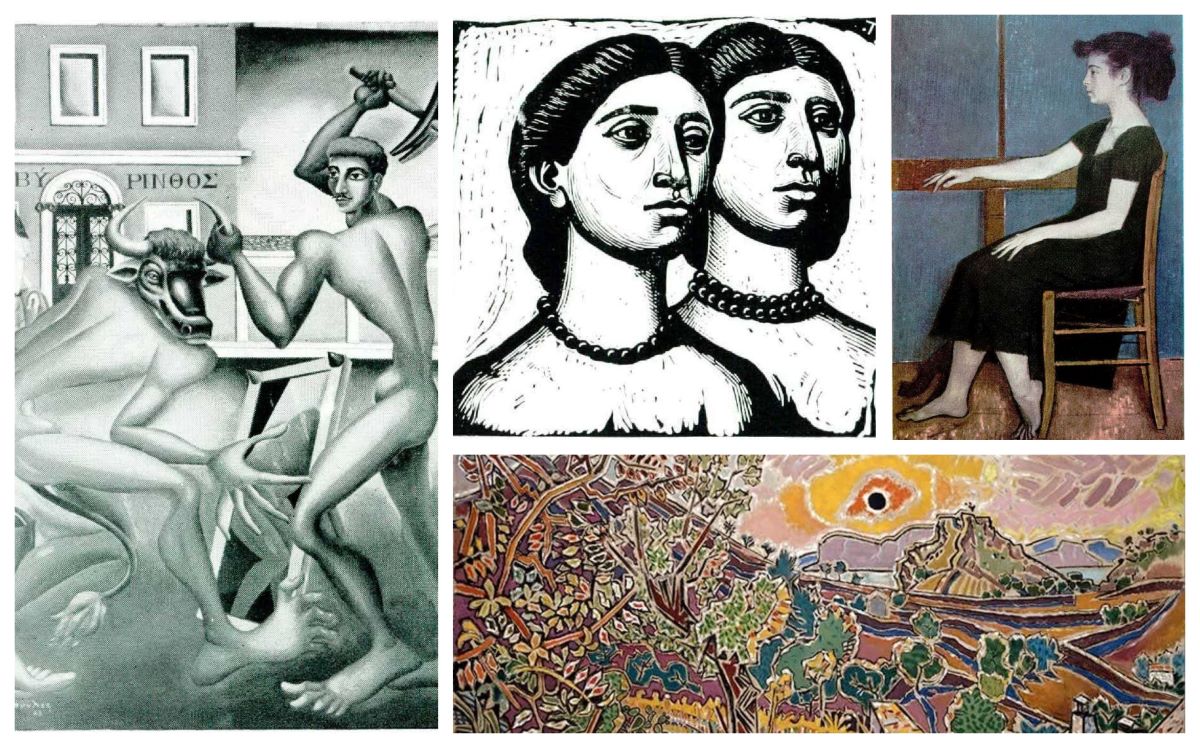

One of the most important aspects of Greek intellectual history that remains understudied has to do with intellectual conceptions, perceptions and critiques of European/Western modernity. It is a question that it was posed most vividly by Nietzsche and his ideas of the ‘Death of God’ and ‘decadence’/’nihilism’ that he associated with his contemporary German and European culture. From then on, artistic modernism and the avant-garde undertook, in a variety of ways, the task of confronting those issues. I raise especially the role of modern art, because in my view, it is through art that we can better grasp the ways Greek intellectuals perceived of modernity.

As far as Theotokas is concerned, some of views on that issue remained constant throughout his life, while some others were modified. More specifically, he believed that the main factors for the ‘crisis of modernity’ were radical technological and economic advances that led to an imbalance in the (Western) human mind and psyche. This extreme imbalance was most evident in avant-garde art movements such as surrealism, expressionism, and futurism. In the 1930s the solution to the ‘crisis of modernity’ that Theotokas offered was a return to core values of the Renaissance and Enlightenment; periods that he associated with ancient Greek values of moderation, freedom, critical rationalism and synthesis. He called this conception ‘New Humanism’ and its aim was, above all, the ‘preservation’ of core Western values that he felt were in danger under the attacks of communism and the degeneration of laissez-faire capitalism and parliamentary democracy.

During this period, in his cultural views orthodox Christianity played a marginal role, since it was conceived mostly as part of Greek historical culture and identity. In the postwar years, Theotokas retained the idea of technoeconomic crisis, embellishing it with the view that I mentioned above, namely that radical economic and technological developments demanded wider, federal state structures. In addition, Christianity, especially Orthodox Christianity (which should not be confused with current Russian Orthodox Christianity) came to the fore in both metaphysical and cultural dimensions. His ‘turn’ to Christianity was not irrelevant to the death of his beloved wife, Nafsika Stergiou in 1959. Metaphysically, Orthodox Christianity was viewed by Theotokas as the solution to the predicament of modern Western man, which brings about the pure loss of existential meaning within industrial, technocratic societies. Culturally, Theotokas expected from the Orthodox Church, as an institution, to play the role of cultural ‘guide’ for the present and future of Hellenism. Therefore, during the postwar period Theotokas had a double, somehow contradictory, vision of modernity. On the one hand, modernity was moving necessarily through radical economic and technical advancements to immense state structures, a process that Theotokas often celebrates. At the same time, on the other hand, this historical process entailed an existential crisis for modern Western man that had to be solved through a return to moderation and Christian metaphysical and moral values.

Read more via Greek News Agenda:

*Interview by: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: MODERN GREEK HISTORY