Art historian Dr. Alexandra Kouroutaki spoke to Greek News Agenda* about the development of art, especially painting, in the newly-founded Greek state, its influences, its evolution and the nascence of the notion of “Greekness”, focusing on the ways Christmas scenes have been depicted by Greek painters of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Alexandra Kouroutaki works as a Lab and Teaching staff (EDIP member) at the School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete. She holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, and a Postgraduate Diploma in French Literature from the School of Humanities of the Hellenic Open University, and is an honours graduate of the Department of French Language and Literature of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

During Ottoman rule, with the exception of some islands, Greece was not influenced by the cultural climate of the Renaissance. At what time did western art begin to be practiced in Greece?

Indeed, the areas of Greece under Ottoman rule were not influenced by the cultural impact of the Renaissance. Two tendencies prevailed at the time: religious painting, which continued with Byzantine tradition, and folk painting. The evolution of Greek painting towards a European art would essentially begin after the liberation, with the declaration of the independent Greek state in 1832-1833. It is considered that the history of Modern Greek painting began with the arrival of the Bavarian prince Otto as the King of Greece.

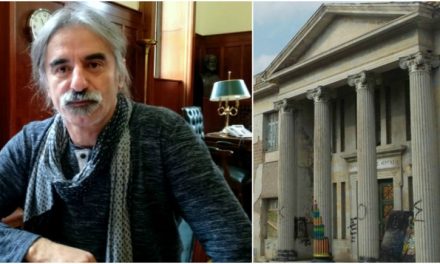

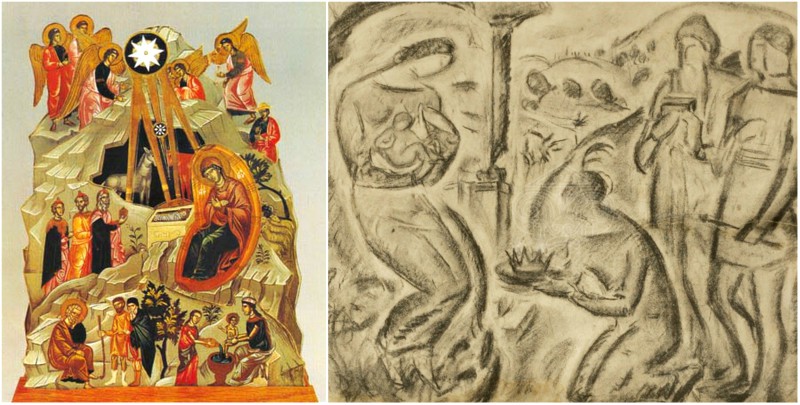

Left: Alexandra Kouroutaki, Right: Theodoros Poulakis (1622-1692), The Nativity of Christ, 1675 (Museo Correr, Venice)

Left: Alexandra Kouroutaki, Right: Theodoros Poulakis (1622-1692), The Nativity of Christ, 1675 (Museo Correr, Venice)

However, we must point out that, long before their union with the mainland, the Ionian Islands and Crete had already developed a remarkable painting tradition, influenced by Western, and in particular Italian, art. It is well established that the Cretan School, since the 16th century, combined elements of Byzantine and Renaissance art, whilst the influence of Italian painting on the Ionian Islands in the 18th century is quite obvious.

A very good example of a work that depicts Christmas and combines Western influences in abundance with elements of Byzantine art is The Nativity of Christ, a work of the progressive iconographer of the 17th century, Theodoros Poulakis, who came from Chania, the Kydonia region, but lived and worked in Venice and Corfu.

What is initially surprising is the fact that the Nativity scene unfolds inside a building, an element of iconography that was introduced to Byzantine art from the West. At the center of the composition, the Virgin Mary surrounded by angels is portrayed holding Baby Jesus with affection, in a composition flooded with light, colour and movement. The liveliness depicted, the animated gestures, the facial expressions and postures, the tendency towards portraiture, the emphasis on expression, the realistic rendering of details such as the folds in the clothing, and of course the evident aim for perspective -aided by the architectural elements of the composition- are influences the artist received from the naturalism of the Flemish school and Mannerist Baroque.

How much did the founding of the Athens School of Fine Arts in 1837 contribute to the development of Greek painting?

Immediately after the establishment of the Greek state and the transfer of the capital from Nafplio to Athens, the School of Fine Arts was founded as a department of the Athens Polytechnic School in 1836. The “School of Arts”, as it was then called, contributed to the development of Greek art, but also to the wider cultural development of the capital and of Greece in general. Unsurprisingly, art on behalf of the state was officially undertaken by foreign artists, mainly Germans, who were invited to Greece by King Otto. They created works of ethnographic character, depicting scenes of the young King’s arrival in Greece and portraits of fighters of the Greek War of Independence. Apart from the foreign artists, there were also notable Greek artists teaching at the School of Arts, such as Nikephoros Lytras, who taught painting at the School for 38 years, urging his students to be open to innovative European movements.

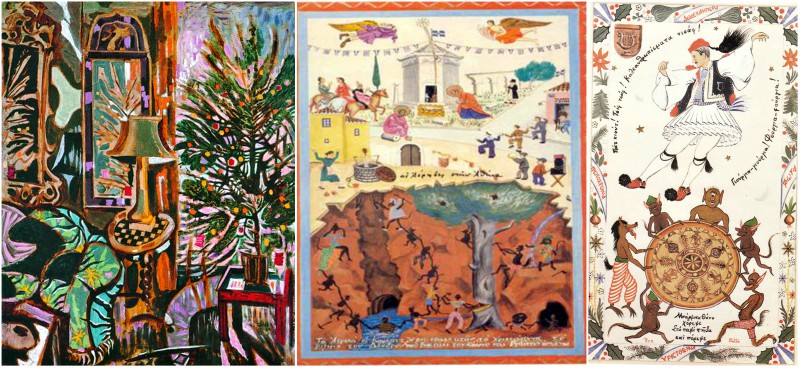

Spyros Vikatos (1878-1960), Christmas tree, c. 1932 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens)

Spyros Vikatos (1878-1960), Christmas tree, c. 1932 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens)

A very popular subject in Modern Greek painting and Modern Greek art in general is Christmas. Who, in your opinion, are the founding fathers of Modern Greek painting and how do they depict Christmas in their works?

Two well-known Christmas works of ethnographic interest are Carols by Nikephoros Lytras, who is considered the patriarch of Modern Greek painting, and the Christmas tree by Spyros Vikatos. Both Lytras and Vikatos were professors at the Athens School of Fine Arts, had studied in Munich and are considered representatives of the Munich School in Greece. They embraced the principles of Academic Realism, i.e., their paintings depicted scenes, whether real or imaginary, of painstaking exactitude and treatment of colour, as well as with a narrative mood.

Lytras’ painting Carols is a realistic and extremely sensitive portrayal of the life of Greeks in the countryside. Greek art takes us with sincerity, simplicity and earnestness on a journey of Christmas customs. Using simple means, Lytras creates an especially lyrical atmosphere, as the moon slowly rises onto a grey yet still luminous sky. A group of boys, of different nationalities, sing carols in the yard of a farmhouse. The housewife, cradling a baby in her arms, listens to the boys holding pomegranates for tipping. Popping his head over the stone fence, a little boy peers curiously at the scene. The artist enters the inner world of the young carol singers so that their expression renders feelings. Moreover, many elements of the composition work on a metaphorical level, and with the use of symbols, Lytras rises above the simple narration of his tale.

In the Christmas tree, the influence of the Munich School is clearly identified. The flawlessness, diligence and meticulousness of the painting are typical of the work of Vikatos in general. Nonetheless, the artist distances himself from the static character of German academism, adopting a milder version. In particular, the painter espouses techniques relevant to the meaningful deepening in colour that remind of the Flemish school of the 17th century. The completeness of form, light, and colour is remarkable in this composition, distinguished for the richness and sensuality of its colours, the variations in light, the use of shadow-light contrasts, the harmony in the whole, and the animation in movements.

Which school influenced most the artists of the newly established Greek state?

As mentioned earlier, 19th century Greek art was chiefly influenced by the “Munich School”. Besides, the rise of Otto to the Greek throne contributed in this direction. The main representatives of the “Munich School” in Greece, other than Nikephoros Lytras, were Konstantinos Volanakis, Nikolaos Gyzis, Georgios Iakovidis and Spyros Vikatos. It should be noted, however, that Greek artists got ahead of sterile academic conservatism, emphasising the expressiveness of figures and the open rendition of emotions.

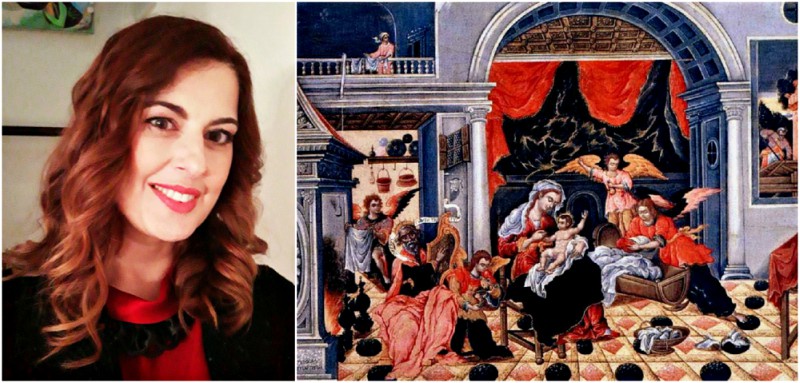

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901), Mother of God, 1898 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens) & Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901), Mother of God, 1898 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens) & Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus

Would you like to tell us something about Nicholas Gyzis, and how he represents the birth of Christ in his works?

Nikolaos Gyzis’s symbolic art really has a special significance in Modern Greek art. A major figure in Modern Greece, Gyzis was obviously influenced by the “Munich School” and academic painting. However, in his religious works he depicts the Virgin Mary in an allegorical and idealistic way, approaching the spirit of European Symbolism. In his Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus painting, the figures are represented as a vision. Gyzis focuses on the tonality of colours in order to reproduce the proper lighting of the scene. The contrast between shadow and light also works allegorically, while the divine infant is portrayed as a source of light and a promise of salvation and redemption for the faithful.

Mother of God is a particularly impressive work by Gyzis. The Virgin Mary is sitting on the throne holding Baby Jesus on her lap, with the cross of martyrdom behind her increasing the dramatic effect. The presence of two radiant angels in prayer accentuates the mystical atmosphere of the scene. The infant Jesus radiates a transcendental light. The angels, as celestial beings symbolise divine transcendence and the triumph of Good, whilst at the bottom of the canvas, Evil, in the form of a snake, appears vanquished. All of these symbols bear witness to the artist’s metaphysical concerns about life after death.

In terms of iconography, what trends and attitudes have been adopted?

Western models have influenced religious painting in Greece since the middle of the 19th century. Church iconography followed the neo-Renaissance style of the Nazarenes, moving away from Byzantine tradition. It must be noted that the establishment of a new ecclesiastical art in Greece had been an imperative need of the State since its founding and demonstrates the wider disposition and effort to transform the country into a modern European state.

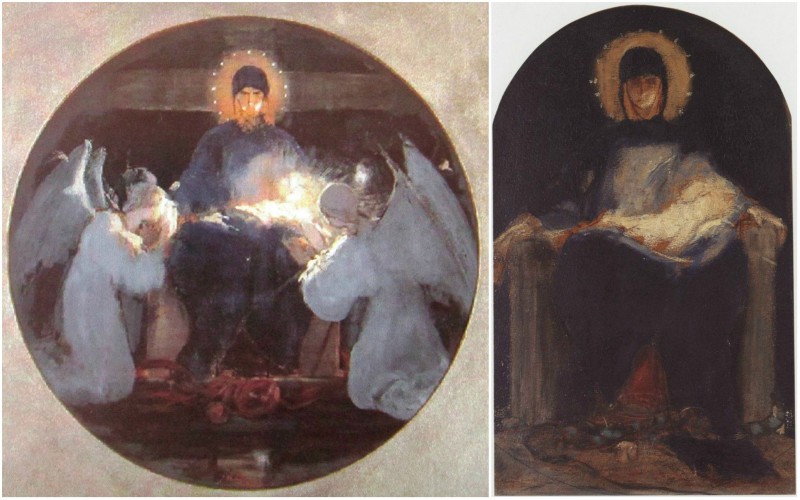

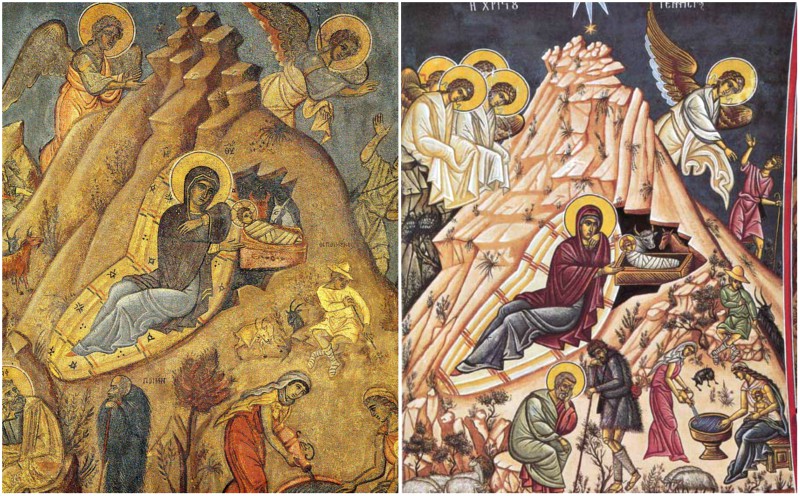

Fotis Kontoglou (1896-1965), The Nativity of Jesus, 1932 (Fresco, Pesmazoglou family chapel, Attica) & The Birth of Christ, 1946 (Fresco, Zoodochos Pigi in Liopesi, Attica)

Fotis Kontoglou (1896-1965), The Nativity of Jesus, 1932 (Fresco, Pesmazoglou family chapel, Attica) & The Birth of Christ, 1946 (Fresco, Zoodochos Pigi in Liopesi, Attica)

After 1950, however, we notice a shift towards Byzantine art, thanks to the catalytic presence of icon painter Fotis Kontoglou. In his paintings, Kontoglou depicts the Birth of Jesus with the spiritual holiness recounted by the Gospels. It is a sacred art that is not simply “painting,” but theology and transcendence. For this reason, the Nativity scene is related with modesty, devoutness and spiritual beauty. The image, of course, retains its historical elements but is not bound by it, while perspective and shadows are eliminated.

Kontoglou painted two frescoes depicting the Nativity of Jesus, one at the family chapel of G. Pesmazoglou, in Kifissia, and the other at the church of Zoodochos Pigi in Liopesi (Paiania). These frescoes appear to be influenced by the frescoes of the monasteries or chapels of Mystras dating from the 14th century. Kontoglou continues in austere style the post-Byzantine artistic tradition without deviations, and manages through the frescoes to depict Christ’s incarnation as a historic as well as spiritual event that combines the celestial with the terrestrial.

Among Kontoglou’s students were two major artists of the “Generation of the ‘30s“, Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos. Engonopoulos painted Virgin Mary in byzantine style, in the strict manner of his instructor. He used Byzantine elements even in his surrealist compositions. Yannis Tsarouchis retained the figurative post-Byzantine form in the depiction of the Nativity scene. In his work Nativity the painter adopts and assimilates creative elements of the Byzantine tradition, such as the clear and austere outline and the muted palette. Light earthy colours and unobtrusive light create a particularly luminous effect.

Yannis Tsarouchis (1910-1989), Nativity, 1946 & Konstantinos Parthenis (1878/1879-1967), The Adoration of the Magi, 1919-1920

Yannis Tsarouchis (1910-1989), Nativity, 1946 & Konstantinos Parthenis (1878/1879-1967), The Adoration of the Magi, 1919-1920

Could you tell us more about the artistic generation of the 1930s and how its main representatives depicted Christmas?

At the beginning of the 20th century, Greek art is strongly influenced by modernism, while the subject of tradition and Greekness becomes an issue of debate. New artists and writers are coming to the forefront: It is the famous “Generation of the ‘30s” that looks for the characteristics of Greekness and combines them with the achievements of the European artistic avant-garde.

Konstantinos Parthenis is one of the most important representatives of Greek art. His work contributed to overcoming conservative academic trends and broke with Munich’s artistic establishment. He defended the artist’s right to seek and create his own personal mode of expression. In his work The Adoration of the Magi, for example, Parthenis depicts with form-shaping freedom aspects of the Byzantine style.

Without doubt, the scene of the adoration of the Magi is distanced from realism, and figures are rendered subtly. Light and shadows are of particular interest. The Virgin Mary, standing on the left of the composition, with Christ in her arms, is surrounded by the indistinct architectural element of the arch, while the Magi worship and offer the gifts. It is worth noting that Parthenis painted religious works that were not however intended to decorate places of worship. These works retain elements of Byzantine art, but are closer to the Western iconographic tradition.

In another allegorical and symbolic composition on the subject of The Birth of Christ, Parthenis retains elements from Byzantine tradition but combines them with modernism. Western influence is found in the colours and in the abstract forms of figures without elements of portraiture. It is an idealistic art that exudes spirituality.

Konstantinos Parthenis (1878/1879-1967), Virgin with Divine Infant – Crucifixion, 1940 – 1942 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens)

Konstantinos Parthenis (1878/1879-1967), Virgin with Divine Infant – Crucifixion, 1940 – 1942 (National Gallery–Alexandros Soutzos Museum, Athens)

A representative work of the idealistic and symbolic art of Parthenis is Virgin with Divine Infant – Crucifixion. Figures are placed in a transcendental space, time is abolished and elements of the visible world are morphed into spiritual depictions. The elemental extinction and the transcendental light refer to the symbolic extensions of the composition. In a particular, idealistic and poetic way, Parthenis combines elements of Byzantine iconography with the achievements of European art and Symbolism in particular.

Parthenis’ student, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, is fittingly considered a member of the legendary “‘30s Generation”. Hadjikyriakos-Ghika uses intense light and colour in his paintings, at a time when the “Generation of the ‘30s” is looking for the characteristics of Greekness.

In his work The Christmas tree, Hatzikyriakos-Ghika renders forms subtly but with impressive aesthetics and elegance of outline. An imaginative game is attempted with scales, with simultaneous layering at different levels. Interesting elements of the project include the intense colour variety, the gleaming shades and the rhythmic organisation of the composition, elements that generally reflect the artist’s contribution to the development of Greek art. Hatzikyriakos-Ghika had said himself he was deeply influenced by the work of Henri Matisse, the subversive French painter who used colour as an architectural device. Equally important was the influence by the cubist artists Braque and Picasso in Paris, in the ‘20s. He thus succeeds, in a unique way, in integrating in his work the achievements of modern European art.

Finally, two works of Panayiotis Tetsis attempt to portray the popular beliefs regarding the Kallikantzaroi, the mischievous goblins of lore. According to a legend prevalent throughout Greece, from Christmas to the eve of the Epiphany, these unsightly little creatures living underground engage in sawing the tree that supports the upper world. At Christmas, however, they visit people on earth to tease them with all sorts of naughty tricks and mischief.

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika (1906-1994), The Christmas tree, 1960 (Private collection) & Panayiotis Tetsis (1925-2016), Kallikantzaroi, c.1978 (Book illustrations)

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika (1906-1994), The Christmas tree, 1960 (Private collection) & Panayiotis Tetsis (1925-2016), Kallikantzaroi, c.1978 (Book illustrations)

With vivid humour and imagination, P. Tetsis portrayed the goblins of Greek folklore Kallikantzaroi in Thanos Murray-Velloudios’ book, Spirits, elves and Kallikantzaroi, which is a study of Greek lore relating to the Kallikantzari, complemented with works of well-known painters. This work depicts the appearance of the Kallikantzaroi in Aerides (a small neighborhood surrounding the Tower of the Winds in Plaka, Athens) on Christmas Eve. The nativity scene is combined with the presence of ordinary people engaged in everyday activities along with the folk legend of the Kallikantzaroi. The work is narrative and it exudes optimism.

In his second work, Tetsis portrays the Kallikantzaroi and their favourite habit, dancing in a pan. The Kallikantzaroi are shaking the pan and the Greek in the pan -who is portrayed in Greek traditional costume (fustanella)- is shrieking joyfully.

In conclusion, Modern Greek artists transplanted in an imaginative, vigorous and original way the atmosphere of Christmas in their artistic creation. Both the artists of the newly established Greek state and those of the legendary “Generation of the ‘30s” adopted elements from the European art of their era, but they also evolved and adapted them to their specific, personal artistic idiom.

*Interview by Marianna Varvarrigou (Intro picture: Nikephoros Lytras [1832-1904], Carols, 1872 [Private collection])

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Athens School of Fine Arts celebrates 180 years; Nikephoros Lytras, the Artist behind Greek Christmas’ Most Celebrated Painting; Konstantinos Volanakis: the Father of Greek Seascapes; Fotis Kontoglou: From “LOGOS” to “EKPHRASIS”; The home and workshop of Yannis Tsarouchis οpens again; Yannis Tsarouchis: Illustrating an autobiography; Nikos Engonopoulos: The Colours of the word and the word of Colours; In Tribute of Panayiotis Tetsis; Ghika – Craxton – Leigh Fermor: Charmed lives in Greece