Dimitrios Koutsogiannis is Professor Emeritus of Educational Linguistics at the Department of Linguistics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and associate president of the Center for the Greek Language. His research interests and publications focus on teaching of Modern Greek as a first and second language, educational discourse analysis, teacher’s training, and digital literacies. He has been a research associate at the Centre for the Greek Language since 1997, responsible for the development of digital resources for the Greek language (e.g., Portal for the Greek Language). His recent research is related to the teaching of Modern Greek in the Diaspora, and the main conclusions are published in the 2024 book “Διδασκαλία της ελληνικής γλώσσας στη διασπορά: μια ολιστική προσέγγιση” [Teaching the Greek language in the diaspora: A holistic approach].

In his interview for Rethinking Greece* Professor Koutsogiannis discusses the digital tools developed by the Centre for the Greek Language (CGL), its initiatives for teaching Greek abroad, the certification of of attainment in Greek, the profile of people interested in learning Greek and finally, on the need draw up a comprehensive policy for the Greek language and its teaching outside Greece.

Since 2017, February 9th has been designated as International Greek Language Day. Would you like to share some introductory thoughts on this celebration and its impact over the years?

The experience so far points to several positive outcomes. On the occasion of this celebration, several interesting events are held, showcasing aspects of the history as well as of the present of the Greek language. We also see numerous engaging activities taking place in schools, mainly diaspora schools, as well as scientific seminars, debates and conferences in academic institutions. All these events and activities are encouraging and constructive, as they did not exist prior to the establishment of this international day of tribute.

On the other hand, there is a significant risk that the content of these discussions and events might be limited to the familiar rhetoric regarding the Greek language, its history, and its importance. One rarely sees serious analyses placing Greek within the modern global linguistic ecology, and even more rarely the formulation of proposals at the level of language policy. I would say that this day needs to be a day of both reflection and planning, especially for institutions and individuals directly or indirectly involved with the language, in terms of what has been done and what needs to be done in the future. Therefore, I consider this interview to be an important opportunity to discuss specific issues and initiatives of the Centre for the Greek Language (CGL), and I would like to thank you for this opportunity.

The CGL also deals with the examinations for the Certification of Attainment in Greek, a programme that commenced in 1999. How has this initiative progressed? Can you provide us with some quantitative and qualitative data?

Yes, with pleasure.

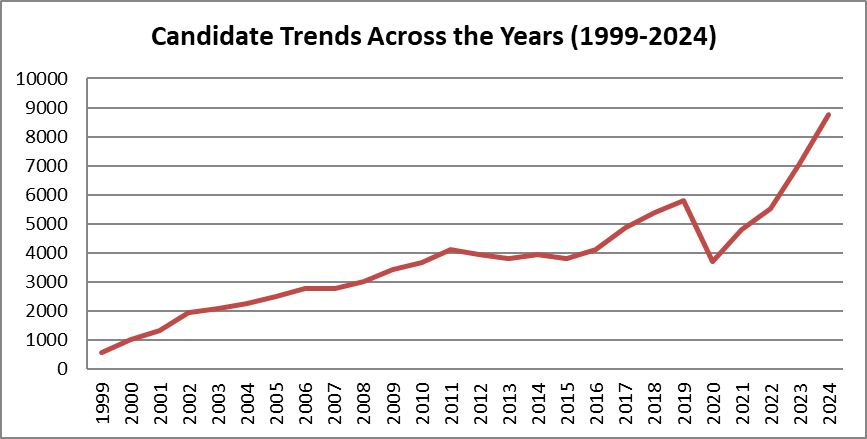

Indeed, this initiative, which began in 1999, has grown into one of our most important programs and a key pillar of our policy for the Greek language. The graph below illustrates the quantitative progress of participation in the Greek language certification exams. We can see that this programme set off in 1999 with very few candidates and a limited number of examination centres. Today, we have 160 examination centres worldwide, even in countries one wouldn’t expect, such as Japan, China, Congo, and Tanzania. The graph also clearly marks a continuous increase in the number of candidates, with the only period of stagnation or even decline being during the pandemic (2020-2021). As shown in the chart, the number of candidates in 2024 reached almost 9,000.

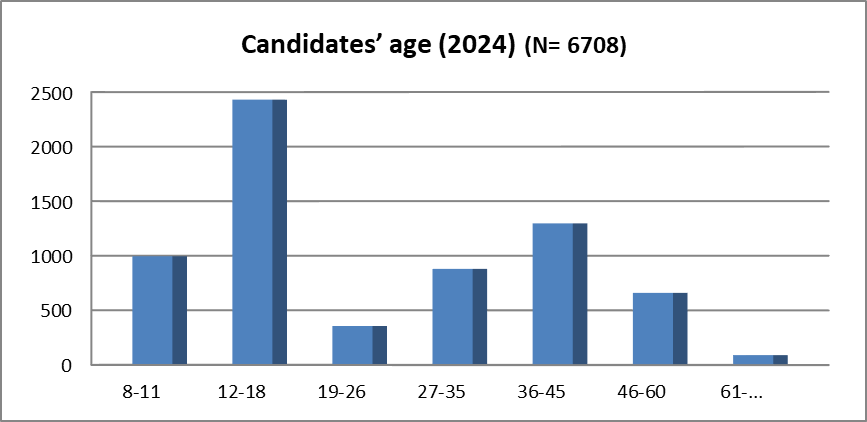

Of particular interest is the info on the age of the candidates[1]. Our data (see next table) indicates that the largest percentage, as might be expected, consists of school-age children (8-18 years old). This critical age group accounts for more than one-third of our candidates. However, there is also a significant percentage of candidates over the age of 35, meaning there is also considerable interest from older age groups in learning the Greek language.

An important aspect is also the profile of the candidates in relation to their connection with Greece. Our analysis shows that the majority (52%) of those taking the exams have some biographical connection to Greece, compared to 48% who do not.

An important aspect is also the profile of the candidates in relation to their connection with Greece. Our analysis shows that the majority (52%) of those taking the exams have some biographical connection to Greece, compared to 48% who do not.

The Certification of Attainment in Greek is a significant programme for several reasons, and I will mention two here. One is that it encourages children to learn Greek in order to use this certificate – which is based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and is recognized both within and in many countries outside Europe – as a qualification for further studies, particularly in educational systems that recognize and support language skills and multilingualism. This is a particularly important incentive for children of the diaspora, who, by learning Greek, not only gain a better command of their heritage language but also acquire an additional qualification that they can use in their studies. The second reason is that it provides a clear framework for teachers and parents to understand their children’s progress in learning the Greek language.

Which groups of people are interested in learning Greek? What is the profile of those who seek to acquire the CGL Greek language certification?

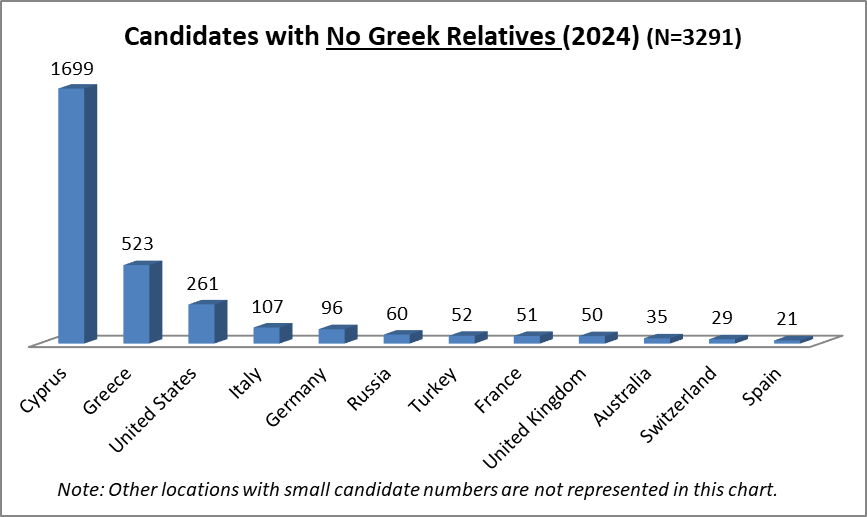

According to our exam data, the number of foreigners learning Greek is significant. As mentioned earlier, it is estimated at 48% of our sample. The two following charts provide some interesting data related to your question. The first bar-chart shows the place of residence of those who do not have any familial connection with Greece and participate in the Greek language certification exams.

It is evident that most of them live primarily in Cyprus, followed by Greece. Knowledge of Greek is thus clearly very useful for them for both social and professional reasons. After Greece and Cyprus, the majority of non-Greek candidates come from the USA, Italy, and Germany, followed by smaller numbers from Russia, Turkey, France, the United Kingdom, etc.

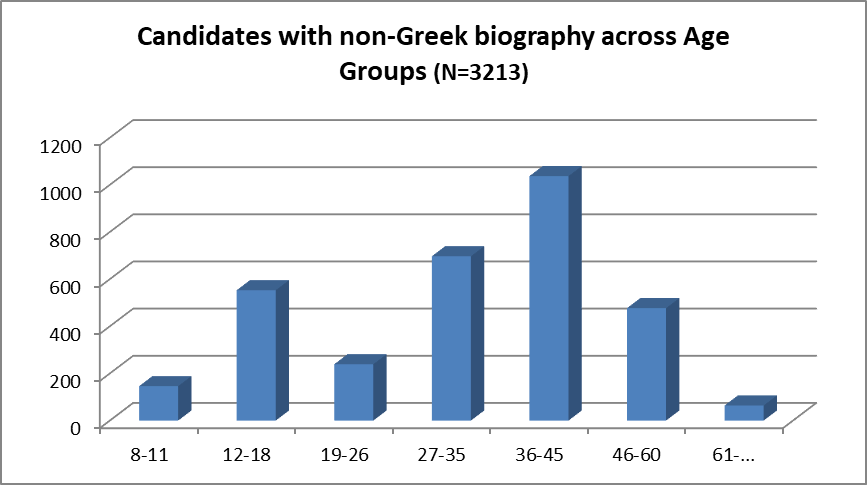

The biggest difference between this group and those of the diaspora is that they tend to learn Greek at an older age, as can be seen from the table below. In contrast to the findings mentioned earlier where the majority of examination candidates are aged 12-18, here we observe that the majority are aged between 27-45.

The above data gives us an initial insight as to your question. However, the issue is not completely covered by our data, primarily because it is only quantitative but also because it is based on those who participate in the certification exams. There are, obviously, thousands of others who are not interested in taking the exam or obtaining certification. In order to get a fuller picture, focused research, both quantitative and qualitative, is needed to attain in greater depth the profile of these individuals, which may vary from country to country and also by age.

Can you briefly tell us about the goals, actions, as well as digital tools the Centre for Greek Language uses, such as the Portal for the Greek Language?

Yes, with pleasure.

At the Centre for the Greek Language we realized quite early, from the end of the 1990s, that the internet was creating a new reality in the field of languages, which is why we made a systematic effort to adapt to the new reality in communication. As a result, the CGL has developed scientifically valid online environments that provide reference tools and a wealth of linguistic material for all periods (ancient, medieval, modern Greek) and fields (language, literature) related to the Greek language and its teaching. The best-known of these are the “Portal for the Greek Language” and the “Digital Resources for the Greek Language“. Through these initiatives, we address a significant condition of the digital age, i.e., that Greek speakers have at their disposal reliable platforms for their daily communication and educational practices. It is no coincidence that these platforms have widespread acceptance and high traffic.

It is important to highlight that our platforms are open and easily accessible from anywhere in the world. In fact, without these digital resources, the online presence of the Greek language would be significantly limited. Furthermore, as the internet plays an increasingly vital role in nearly every aspect of daily life, this absence would be especially harmful as it would deprive the Greek language of a crucial and widely used space for application and growth.

What are the specific challenges of preserving the Greek language for the diaspora? Are there any CGL initiatives for teaching Greek abroad?

There are several CGL initiatives in this direction by way of specific programmes that have been or are being implemented. I will mention two recent ones. As of this year, we began offering remote Greek language teaching courses and we will systematically expand this initiative, the significance of which is obvious, over the coming years.

Another exciting initiative is the establishment of the international group of special scientific interest D.EL.EXO. in 2022. It focuses on the teaching of Greek outside of Greece and provides the organizational framework for developing and advancing debate, criticism and research related to the teaching of Greek worldwide. In other words, it could be said that it is the digital platform for bringing together the scientific forces involved in the teaching of Greek globally. This team has already launched many initiatives, organized two seminars, and is organizing a large international conference (5-7 February 2026) on the teaching of Greek around the world which will involve scientists, educators, and Greek communities.

Additionally, we are already in the process of planning the creation of a digital environment for teaching the Greek language, which will consist of a modern educational teaching platform, accompanied by an abundance of digital language resources that can be used in teaching. At the same time, we have already worked on the utilization of Artificial Intelligence in the teaching of Greek. These are projects that are expected to be ready within the next three years.

I would also like to address the first part of your question, regarding the specific challenges that the preservation of the Greek language for the diaspora involves. This major issue was addressed in a recent study we conducted with children and parents from the diaspora in Australia and Germany, which was funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI). In the volume “Διδασκαλία της ελληνικής γλώσσας στη διασπορά: μια ολιστική προσέγγιση” that is based on this research, we not only highlight the significant challenges that exist but also lay out specific proposals for teaching the Greek language in the diaspora. Hopefully, these will be considered.

What kind of interventions would be useful for a language, especially one with relatively few native speakers like Greek, to survive in today’s globalized digital environment?

This is a critical question and exactly what has guided our actions over the past 20 years. It is now evident that the existence of reliable linguistic resources on the internet is an indispensable requirement for any language, especially for less spoken languages such as Greek. One only has to consider that, as we mentioned earlier, if we removed the tools and resources freely available through the CGL, the needs arising for learning and teaching of Greek would be covered -to a significant degree- by subjective personal opinions expressed on social networks.

However, digital tools alone are not enough; the initiatives and actions undertaken and those we are planning are not enough. It is time to draw up a comprehensive policy for the Greek language and its teaching outside Greece. Such a policy must begin with an analysis of the global linguistic context, place Greek within this framework, register existing structures (both digital and conventional, inside and outside Greece – Cyprus), institutions, and practices (e.g., teaching), and formulate proposals to be implemented by competent ministries and as well as agencies outside Greece. I believe that in the context of such an effort, cooperation with Cyprus should be pursued, as we share common goals and our cooperation so far[2] has been highly productive.

* Interview to Ioulia Livaditi / Translated from Greek to English: Magda Hatzopoulou

Read more from Greek News Agenda

[1] In each table, N denotes the number on which the results are based. This number varies either because some candidates submitted handwritten applications at the local examination centres or/and because answering was not mandatory.

[2] A five-year memorandum of cooperation for Greek language learning is being implemented between the Ministry of Education of Greece and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Cyprus.

TAGS: EDUCATION | GREEK LANGUAGE