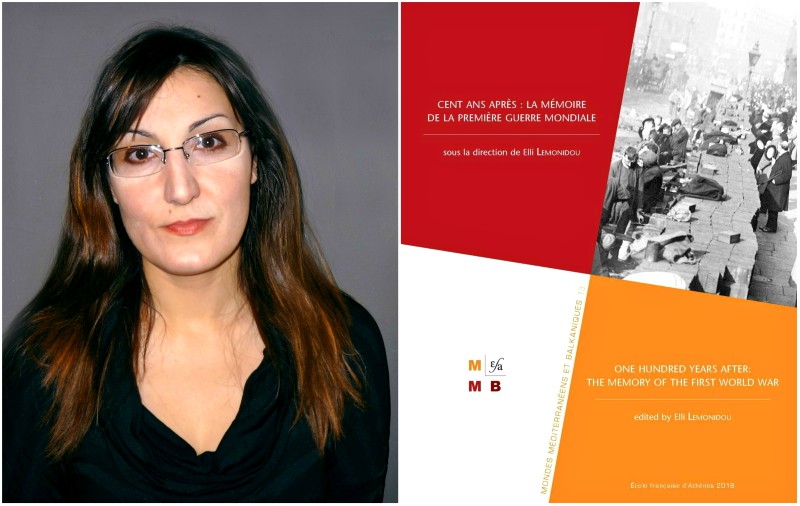

Elli Lemonidou is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Greek and European History at the Department of Cultural Heritage Management and New Technologies of the University of Patras. Her research interests include Modern and Contemporary History, History of International Relations, Cultural History, History and New Technologies, Public Uses of the Historical Past. Her research focuses on the two world wars and the public uses of history.

Her latest book bears the title History on the Big Screen. History, Cinema and National Identities (Taxideftis, Athens 2017); she also edited the collective volume One hundred years after: The memory of the First World War / Cent ans après : la mémoire de la Première Guerre mondiale (French School of Athens, bilingual edition, Athens 2018).

Greek News Agenda’s sister publication, GrèceHebdo, interviewed* Elli Lemonidou about the heterogeneous memory of the Great War in Europe, which remains “a forgotten war” in Greece, contrary to the dominant position of the 1940s in historiography and public debates in Greece. Lemonidou gives a definition of Public History (“Public Uses of History” in France) and speaks of its various expressions in the public space, emphasising the cinema.

Greek troops in Thessaloniki departing for the front (National Historical Museum/ Thessaloniki History Centre)

Greek troops in Thessaloniki departing for the front (National Historical Museum/ Thessaloniki History Centre)

One hundred years ago, the First World War ended; you have edited the recently published bilingual (French and English) volume One hundred years after: The memory of the First World War, which presents the diverse forms of the collective memory of the conflict in Europe. We can certainly say that Europe’s memory of the “Great War” is neither uniform nor homogeneous. Could you tell us what causes collective memories to be so heterogeneous from one country to another?

It is true that there’s no single type of collective memory of World War I in Europe, something reflected in the contributions to this volume, which cover many different national examples. As the professor and academic George-Henri Soutou points out in his text, we can perhaps speak of some points of convergence in the memory of this war on a wider European level, but not of a single narrative.

This phenomenon can be explained in many ways – there is, however, one central point where we must focus our attention. The Great War has dramatically affected almost all countries on the European map, whether they were among the warring countries, the ones that remained neutral or those established at the end of the war. However, the ways memories are triggered and references are made to this war vary considerably, bearing a distinct national character, since they have been shaped to a large extent by the particularities of each country’s national history and socio-political characteristics that prevail in different periods.

Venizelos reviews a section of the Greek army on the Macedonian front during the First World War, 1918, accompanied by Admiral Pavlos Koundouriotis (left) and General Maurice Sarrail (right). (Wikipedia)

Venizelos reviews a section of the Greek army on the Macedonian front during the First World War, 1918, accompanied by Admiral Pavlos Koundouriotis (left) and General Maurice Sarrail (right). (Wikipedia)

Despite the fact that in several European countries the Great War occupied, and still occupies, a central place in the collective memory and the public sphere, in Greece this important historical event is, as you say, “a forgotten war”. How can one understand Greece’s disinterest in World War I?

Several reasons may explain this lack of interest in the First World War. There are three factors contributing to this phenomenon.

First of all, World War I took place in the midst of a decade that was decisive for the history of modern Greece. It began with the military and diplomatic triumph of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and ended with the so-called “Asia Minor Catastrophe” and the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (1922-1923), which marked the final end of the “Great Idea” (Greek irredentism). The glorious memory of the Balkan Wars and the trauma of the Asia Minor Catastrophe almost completely overshadowed intermediate developments, despite their great consequence for the final outcome of Greek issues.

Secondly, official Greek participation in World War I was short-lived, given that it essentially became involved in 1918, the last year of the war. The events that unfolded on Greek soil in the years prior to WW I, despite being directly related to the war, were of a fragmented nature and indelibly linked with the particular issue of the National Schism on the domestic political scene; as a result, it was impossible to form one single dominant narrative regarding the country’s involvement in the First World War.

A third and most decisive factor concerns the critical role of the 1940s, a decade that was traumatic in many ways, overshadowing not just WW I, but also every other event in modern Greek history, both in historiography and in collective memory.

The Greek population of Smyrna watching from terrace of local Greek sport club “Sporting” for entering of Greek navy ships in the Bay of Smyrna, 2 May, 1919 (Wikipedia)

The Greek population of Smyrna watching from terrace of local Greek sport club “Sporting” for entering of Greek navy ships in the Bay of Smyrna, 2 May, 1919 (Wikipedia)

You argue that, unlike World War I, the events of the 1940s and World War II still echo in Greece, whether we refer to historiography and academic research or to public discourse.

It is true that the 1940s still have a dominant position in public and academic debate about Modern Greek history. In fact, the period 1940-1949 has not yet been fully historicised: there is still a significant number of people who experienced the events of that time and who often add their (admittedly much sought after) testimonies to this debate.

Moreover, the extremely traumatic nature of the events of this period, combined with the socio-political conditions of the following decades in Greece, delayed the assimilation of very important aspects of this decade (i.e., the Greek Civil War or the fate of the Greek Jews) into scientific research. There are, thus, many issues that remain open to new approaches, fully justifying the unending interest in the subject.

The experience of recent years has clearly demonstrated that several of the major challenges relating to the history of the 1940s are still relevant and form an essential part of public debate today. Characteristic examples include the issue of German war reparations, the treatment of Greek Jews, and the ideological axes of the Civil War. These questions maintain their dynamic, which explains the enduring interest in the layered history of the 1940s.

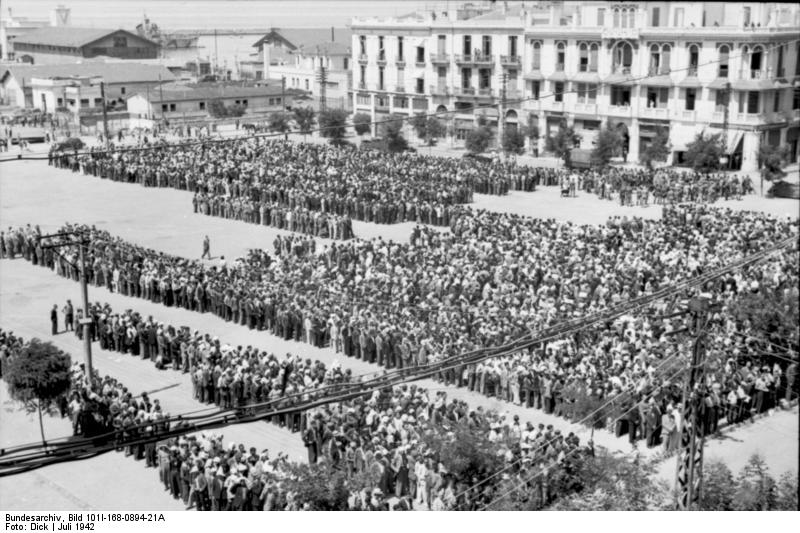

Registration of the male Jews by Nazis at the centre of Thessaloniki, July 1942 (Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv)

Registration of the male Jews by Nazis at the centre of Thessaloniki, July 1942 (Wikipedia/Bundesarchiv)

Let’s talk about “Public History” which is another area of research for you: it is a separate field of history that has attracted academic interest in recent years. What do we mean by this term and what are the main expressions of “Public History” in Greece?

Public History is a relatively new field of study. However, despite its rapid growth in recent years, there is no universally accepted definition of the term. On the basis of the most commonly accepted description, we could say that Public History refers to narratives about important issues of the past, which do not necessarily go through the channels of academic history. To give some examples, Public History includes the management and narration of the past through cinema, museum exhibitions, TV shows, online posts, as well as school-taught history or institutionalised memory via national commemorations and celebrations.

In Greece, systematic Public History research and study has been with us for about two decades, although examples of such studies actually have deep historical roots – one need only consider how deeply perceptions of the past are influenced by factors such as literature and public ceremonies and celebrations. In recent years, Public History has been enriched by a spectacular expansion and proliferation of related actions and initiatives – we can mention, for example, an increased interest in oral history, the organization of historic walks and frequent broadcasts of history programmes on radio and TV.

Hands up, Hitler (Psila ta heria, Hitler), 1962, de Roviros Manthoulis.

Hands up, Hitler (Psila ta heria, Hitler), 1962, de Roviros Manthoulis.

You mentioned cinema and I know that you have recently written a book about the relationship between history and cinema (H Iστορία στη μεγάλη οθόνη [History on the big screen, Athens 2017). Could you tell us how Greek contemporary history has been rendered in Greek films?

Although there have been a significant number of Greek films drawing themes from contemporary Greek history, their imprint is still rather limited compared to other national film industries. In the heyday of commercial cinema (1950s-1960s), Greek directors had, with few exceptions, treated historic subjects in a conventional and one-dimensional manner, due to the political and social restrictions of this period. It wasn’t until after 1970 that the New Greek Cinema -with Theo Angelopoulos and Pantelis Voulgaris among its major representatives- attempted a fresh look at recent controversial historic events, while after 1990 the attention of filmmakers focused on the burning issue of migration and identities within Greek society.

The traveling players, 1975, by Theo Angelopoulos ©Greek Film Archive

The traveling players, 1975, by Theo Angelopoulos ©Greek Film Archive

You have also focused your research on the ways “sensitive” issues are handled in school. What is the situation today in Greek schools?

This issue today preoccupies many historians as well as education theorists. Sensitive or contentious issues of the past generally come with a traumatising dimension, provoking heated public debate or even social conflict, and thus require extremely cautious management in the classroom. Characteristic examples of such subjects include the Holocaust and the Algerian war at French schools, and the Greek Civil War in the Greek educational system. Modern research converges on the need to include sensitive and traumatic issues in the teaching of history at school. Given that these issues are inherently open to multiple and often contradictory interpretations, their teaching is considered essential for the development of critical thinking and civic awareness among students. As many researchers have pointed out, historicisation is a prerequisite in the process of overcoming historical trauma at a collective level and this is achieved through narration (instead of silence), extensive study of all its aspects and by integrating it in a specific historical context. Thus, unilateral perceptions of these issues may be avoided, while conditions are created for the smooth integration of young citizens into an increasingly complex and demanding social environment.

* Interview by Magdalini Varoucha. Translation into English by Nefeli Mosaidi.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Ntina Tzouvala on the history of international law and its impact on the Balkans; Gavrilis Lampatos on the Communist Party of Greece and the country´s public history; Henriette-Rika Benveniste on the history of Greek Jewish communities and the rise of the extreme right in Europe