Life in the Tomb (1924) by Stratis Myrivilis is a landmark war novel, and by far the most famous work written in Greece on the subject of the First World War. Just like Erich Maria Remarque’s international best-seller All Quiet on the Western Front –which it predates– it is inspired by the author’s own harrowing experiences in the trenches.

Greece in WWI

The outbreak of the First World War found Greece already in a state of turmoil; already from the turn of the century, strong anti-monarchist sentiments were stirred, especially due to the king’s overt involvement in politics. This division, expressed in the tension between the Crown and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, was deepened during the Balkan Wars (1912-14).

Venizelos’s disagreement with Constantine I over Greece’s stance in WWI (with the former wanting to side with the Allies and the latter insisting on neutrality) led to the “National Schism”, with the country split between two governments. Greece was eventually united and officially joined the Allies in 1917; its involvement proved beneficial for the national causes, since it was rewarded with territorial acquisitions – although a large part of these were subsequently lost to Turkey in the Greco-Turkish War that followed.

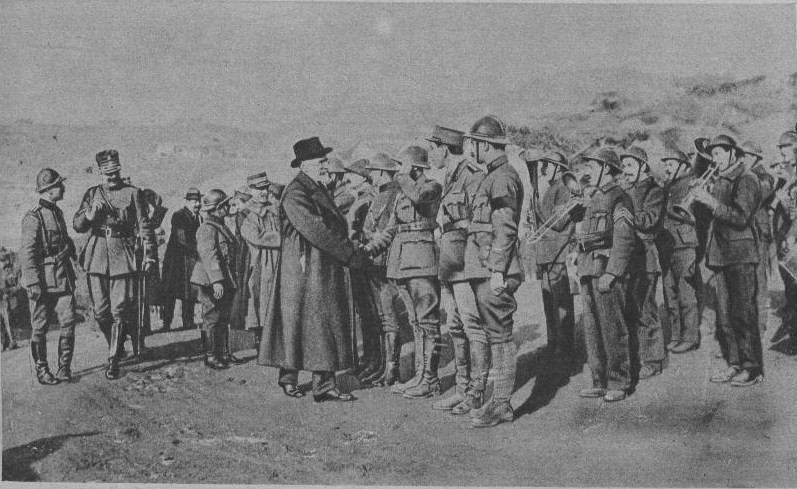

Eleftherios Venizelos with French General Auguste Gérôme, inspecting the Greek Army, December 1918 (From Le Miroir n°222 via Wikimedia Commons)

Eleftherios Venizelos with French General Auguste Gérôme, inspecting the Greek Army, December 1918 (From Le Miroir n°222 via Wikimedia Commons)

To date, WWI and the Greek involvement in it is not often discussed in the country’s public discourse. The “Great War” is largely perceived as a foreign conflict, unlike WWII, where Greeks spontaneously united against armies invading their own lands. Overshadowed by the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 and the ensuing tragedy known as the Asia Minor Catastrophe, as well as eclipsed by the heroic deeds of the Greek Army and Resistance in WWII, the First World War remains largely “unsung” in Greece, making Life in the Tomb all the more valuable for its depiction of an important chapter in the country’s history.

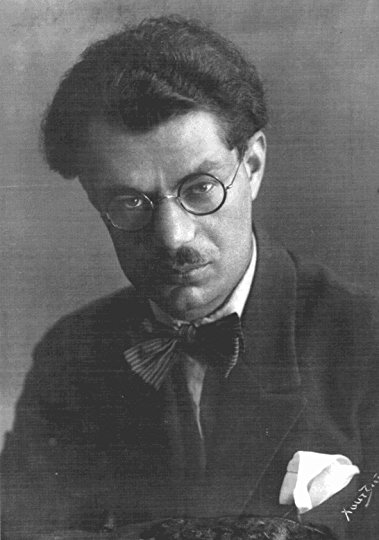

Stratis Myrivilis

Myrivilis was one of the most prominent representatives of the so-called Generation of the ’30s, Greece’s dominant Modernist movement in Arts and Letters, which combined folk and modern artistic elements in a quest for the concept of “Greekness”.

Born Efstratios Stamatopoulos in a village on the island of Lesbos (at the time still part of the Ottoman Empire) in 1890, he received an education there and became a schoolmaster, before deciding to enroll at the University of Athens in 1912. Later that year, however, he would volunteer to fight in the Balkan Wars (where Greece and its allies faced the Ottoman Empire and then Bulgaria). He was wounded in the Battle of Kilkis–Lachanas against Bulgaria in 1913 (Second Balkan War), receiving a medal for his service; he consequently returned to Lesbos and settled in Mytilene, the island’s capital.

In Mytilene, he worked at the newspaper Salpinx (Trumpet) writing vignettes. There he published his first book, a short story collection, under the pen name Myrivilis, which he had used since his first venture as a writer (a short story for a contest); the pseudonym was inspired by the name of a mountain slope in his home village, and he kept it for his entire career.

In Mytilene, he worked at the newspaper Salpinx (Trumpet) writing vignettes. There he published his first book, a short story collection, under the pen name Myrivilis, which he had used since his first venture as a writer (a short story for a contest); the pseudonym was inspired by the name of a mountain slope in his home village, and he kept it for his entire career.

Myrivilis was an ardent supporter of Eleftherios Venizelos. When Greece entered the “Great War”, he once again enlisted to fight on the Macedonian Front; during his service, he starts writing his book, inspired by his own experiences. In 1920, he married Eleni Dimitriou, a young Greek refugee from Asia Minor. He also fought in the Greco-Turkish War; following Greece’s defeat in 1922, he returned to Lesbos and resumed his collaboration with Salpinx and other local newspapers, publishing short stories, articles, vignettes and poems.

In 1923 he founded the weekly newspaper Kambana (Bell), where he was editor-in-chief and expressed the antimilitarist ideas he had developed through his experiences in combat; Life in the Tomb was first published in this newspaper.

In 1923, Ilias Venezis, a young Greek from Anatolia, arrived in Lesbos to join his refugee family, having just been released from the notorious Turkish Labour Battalions in Asia Minor; Myrivilis met him and incited him to record his experiences as a survivor of the labour camps. The result was the autobiographical novel Number 31328: The Book of Slavery, which Myrivilis would publish in Kambana in serialised form, in 1924. Venezis would go on to become a successful writer –also part of the “Generation of the ’30s”– especially famous for his book Land of Aeolia.

Myrivilis moved to Athens with his wife and children in 1932; there he continued working for newspapers and magazines (including some of the capitals most important printed media, like Kathimerini, Acropolis and Nea Hestia), and became a member of the Journalists’ Union of Athens. Later he would also collaborate with Athens Radio Station, the first radio station in Greece, while from 1946 to 1950 he was Programme Director at the National Radio Foundation, the country’s public state broadcaster.

Apart from Life in the Tomb, which remains his most important and famous book, his most prominent works include the novels The schoolmistress with the golden eyes (1933) and The mermaid Madonna (1949), which form –together with Life in the Tomb– , an unofficial trilogy on Greek (war) history of the first quarter of the 20th century; they are in fact his only works to have appeared in English.

In 1940, he shared with Ilias Venezis the prize for best novel (for The blue book and Serenity, respectively) at the 1939 State Prizes for Literature. In 1958, he became a member of the Academy of Athens. He was a three-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature (1960, 1962, 1963). In the final years of his life he suffered from cancer; he died in Athens on 19 July 1969 from bronchopneumonia.

Greek troops at Strymon River (near the Bulgarian borders), 1917/18 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Greek troops at Strymon River (near the Bulgarian borders), 1917/18 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Life in the Tomb

Inspired by the format of the epistolary novel, Myrivilis wrote the book as a series of letters addressed by the young Sergeant Antonis Kostoulas to his loved one, and supposedly discovered following his death in combat. In these letters (some of which mostly resemble diary entries) Kostoulas describes his experiences from the trench warfare on the Macedonian Front in 1917-1918.

Drawing from his own life, the author presents the realities of war through various anecdotes, creating a heterogeneous but vivid narrative. He portrays the horrors and bloodshed of the front, while also offering his unique perspective into the human condition. Through his tragic, but also bittersweet and –even, sometimes– funny stories he foregrounds “the voice of the soldier”, dismissing and the fables of “pseudo-chivalry” presented by those who decide to wage war out of “fear, fanaticism or vainglorious conceit”. As John Taylor writes in his book Into the Heart of European Poetry (2008), Life in the Tomb is “the diary of a volunteer who lose his illusion and grows capable of the most penetrating self-observation”.

The book draws its title from a famous phrase used in the Greek Orthodox Matins of Holy and Great Saturday, celebrated on Good Friday night, a service known as The Lamentation at the Tomb; it is the first verse of the first section of the Enkomia (“Lamentations/Praises”), sung before the Epitaphios (an icon symbolising the body of Jesus Christ following his deposition from the cross). The words I zoi en tafo (“Life in the grave/tomb”) are part of the phrase which roughly translates as “Christ, Thou (who art) Life hast been laid in a grave”.

In Greek, the word tafos (grave) is similar to the word tafros, which means “ditch” or “moat”, but was also used to signify “trench”. Hence, the title is a pun, alluding to the soldiers’ lives in the trenches, but also to their potential death, as well as the loss of their youth, innocence and hopes.

In Greek, the word tafos (grave) is similar to the word tafros, which means “ditch” or “moat”, but was also used to signify “trench”. Hence, the title is a pun, alluding to the soldiers’ lives in the trenches, but also to their potential death, as well as the loss of their youth, innocence and hopes.

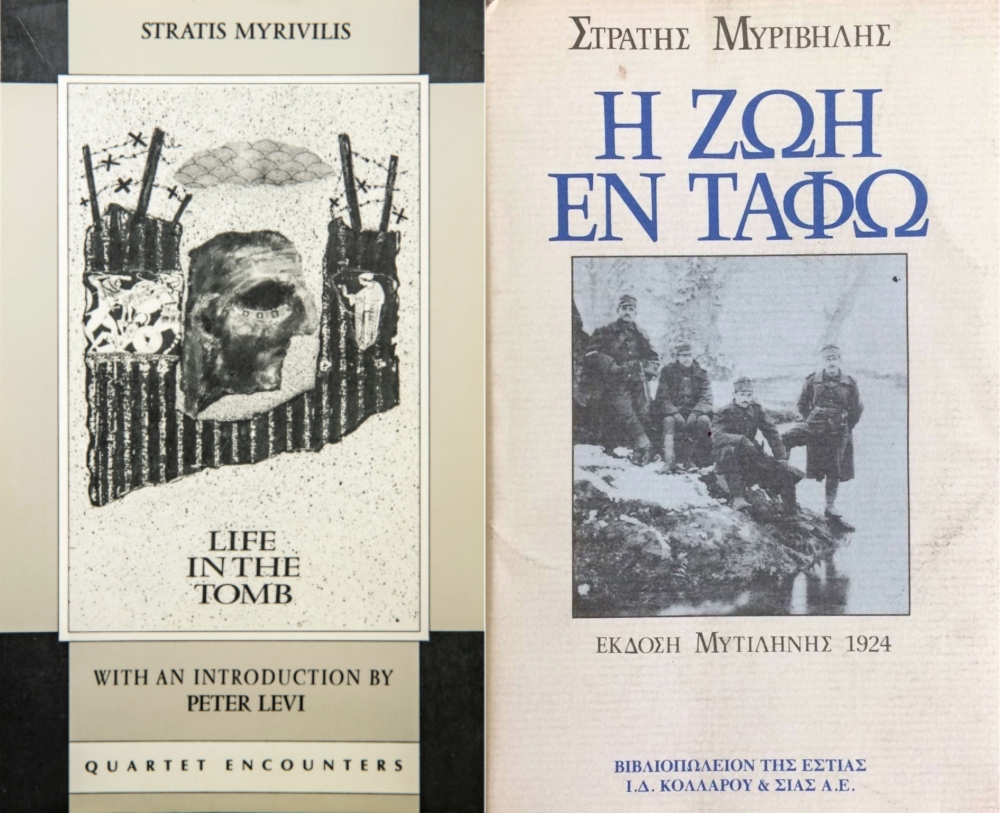

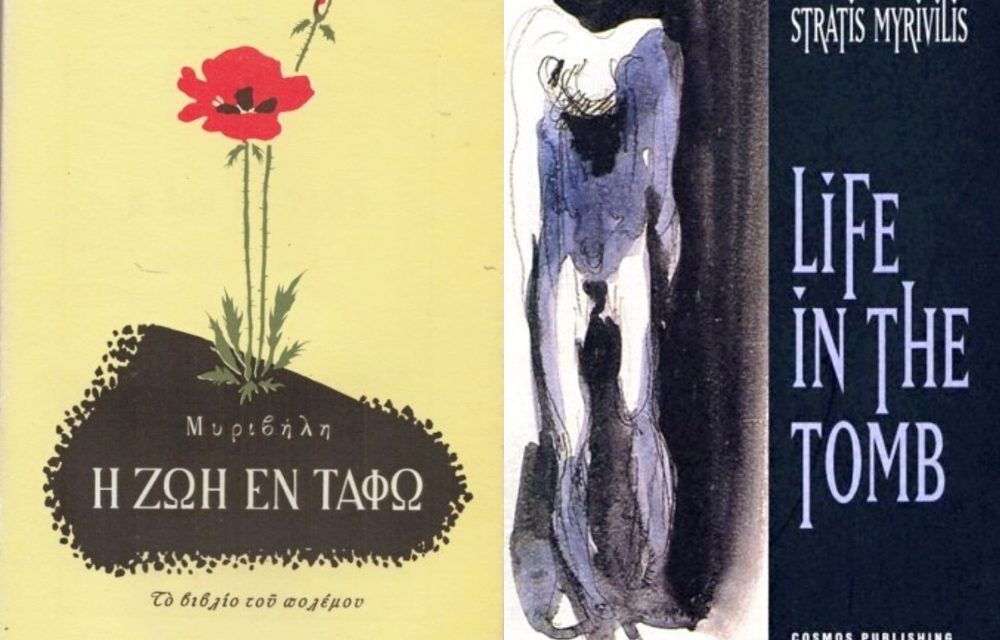

A chapter of the book was published in the newspaper Nea Ellada (New Greece) in Thessaloniki in 1917, when Myrivilis was still in active service. The novel was serialised in the Mytilini-based newspaper Kambana, from April 1923 to January 1924, and then released in a single volume in 1924.

Six more editions followed (in 1930, ’32, ’46,’49, ’54 and 1955), sometimes with significant changes, including the addition and/or the split of chapters by the author, which even result in the addition of characters and storylines. Myrivilis basically saw his magnum opus as a work in progress throughout his life. The first and second –notably more concise– editions are today available in Greek. It was in fact the 1930 edition (the second one, which already had 16 more chapters than the first one) that had made Myrivilis a household name, thanks to its impressive success.

The book has been translated into 14 languages; it first translation was in Albanian, in 1932. It has since appeared in French, Serbian, Russian, Romanian, Polish, Czech, Italian, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Turkish, German and Spanish. It was published in English in 1977, translated by Peter A. Bien; it was based on the book’s third edition, which featured 57 chapters. C.M. Woodhouse had written in the Times Literary Supplement that the translator had “turned a Greek masterpiece into something not much less than an English one”.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: “Land of Aeolia” by Ilias Venezis; “Freedom and Death” by Nikos Kazantzakis; Lesbos – An island of culture and history; The tradition of the Epitaphios procession

N.M.

![Reading Greece: A tribute to [FRMK], a Literary Magazine on the Poetic Phenomenon and its Relation to Arts and Society](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/03/frmk_INTRO_1-440x264.jpg)