Maria Boletsi is Endowed Professor of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Amsterdam, where she holds the Marilena Laskaridis Chair since January 2018. She is also assistant professor at the Film and Literary Studies Department of Leiden University. She has been a Stanley Seeger Research fellow at Princeton University (2016) and a visiting scholar at Geneva University (2016) and Columbia University (2008-2009).

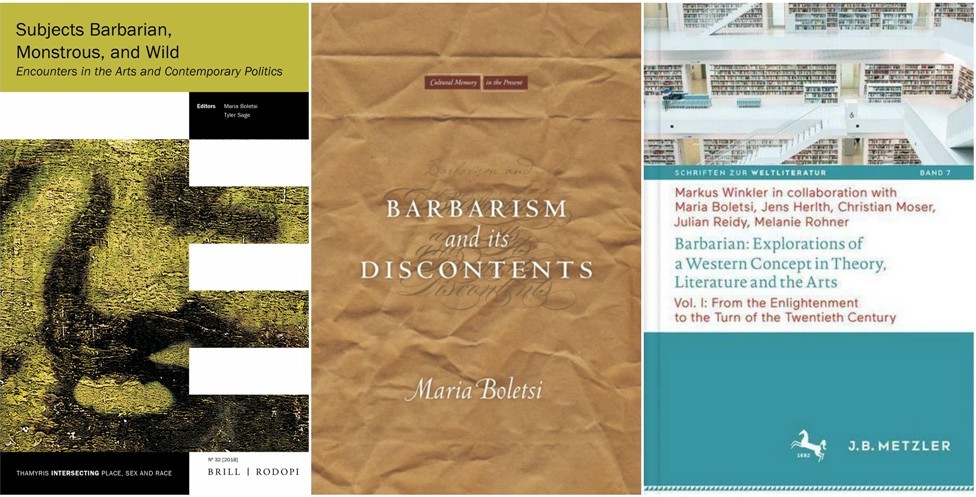

Professor Boletsi’s work is situated in the fields of Modern Greek literature and culture, comparative literature, literary and cultural theory, conceptual history, and cultural analysis. She has published on several topics, including the cultural history of barbarism, the concept of crisis, post-9/11 literature and political rhetoric, Modern Greek, English, and Dutch literature, and alternative ‘grammars’ and subjectivities in the context of the Greek crisis. She is the author of Barbarism and Its Discontents (Stanford UP, 2013) and co-author of Barbarian: Explorations of a Western Concept in Theory, Literature, and the Arts, Vol. 1(Metzler, 2018), and Of the Lightness of Literature (published in Dutch: De lichtheid van literatuur, Acco, 2015) on the role of literature in the multicultural society. She has co-edited the volumes Barbarism Revisited: New Perspectives on an Old Concept (Brill 2015) and Subjects Barbarian, Monstrous, and Wild: Encounters in the Arts and Contemporary Politics (Brill, 2018). She is currently writing a book on spectrality in the poetics of the Greek poet C.P. Cavafy and his poetry’s contemporary afterlives.

Maria Boletsi spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the cultural and literary encounters between Greece and the Netherlands, on the work done by the Department of Modern Greek at the University of Amsterdam and the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation, and on how the shift from language to culture and history in Modern Greek studies programmes can yield innovative results. She discusses her concept of Cavafy’s “poetics of the spectral” and using his poem “Waiting for the Barbarians” as a starting point for exploring the trajectories of the term “barbarism” and the ‘civilization versus barbarism’ scheme in Western public rhetoric. On the subject of Greek art during the crisis, she posits that although we should resist exoticizing or colonially inflected frameworks, disavowing the politicization of Greek art is not really an option. Overall, Boletsi argues that “there is definitely a momentum for shaping a critical field of Modern Greek studies; using this momentum, we can turn the ‘islands’ of Modern Greek departments into dynamic networks—or archipelagos.”

In your inaugural speech as Marilena Laskaridis Professor of Modern Greek Studies you referred to the special connections between Greece and Netherlands. Could you talk to us about that?

When thinking about cultural encounters between Greece and Holland historically, the first example that probably springs to mind is Adamantios Korais, who lived in Amsterdam as a young man between 1771 and 1777. Although he failed as a merchant there, Amsterdam broadened his intellectual horizons and brought him in contact with European mentalities and bourgeois values. The picture that his servant Stamatis Petrou sketched in his Letters from Amsterdam—of a Korais susceptible to the temptations of this liberal society—is a delightful source of information about Korais’ Amsterdam years. But there is a lot more about (and by) Korais to be found in the special collections of our library at the University of Amsterdam—one of the richest library collections in Byzantine and Modern Greek studies in Western Europe. We keep, for example, Korais’ correspondence with the Dutch philhellenist and philosopher Jeanne Wyttenbach-Gallien, who corresponded with Korais about giving financial aid to the Greek Revolution.

Beyond Korais, what is perhaps less known is that the first edition of Cavafy’s poems was published in the Netherlands, in 1934: it comprised twenty-five poems translated by neo-Hellenist and byzantinologist Gerard Hendrik Blanken, who got to know Cavafy’s poems through professor D.C. Hesseling. Hesseling had received some of Cavafy’s feuilles volantes—the pamphlets with his poems Cavafy circulated to friends and people he respected—and passed them to Blanken (his daughter still has them, as she told me). Blanken continued translating and studying Cavafy throughout his life. Besides Blanken’s translations, other valuable Dutch translations of Cavafy continue to be published—this year only, a revised edition of Cavafy’s collected poems by Hans Warren and Mario Molegraaf and a new translation of 73 poems by LudovieK Jansen-Stubij appeared. Cavafy is a beloved poet in the Netherlands. I still remember my surprise when I accidentally ran into his poem “Κρυμμένα” (“Hidden Things”) one evening, written in Greek on the wall of a building in Leiden. It was one of the “wall poems” spread throughout this city, and Cavafy was the only Modern Greek poet included in this project. That was when I first came to the country in 1999, but the poem was still there when I last checked.

If Blanken’s was the first ever foreign edition of Cavafy’s poems, the first history of Modern Greek Literature in a foreign language, written in 1921, was also by a Dutch scholar: professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek in Leiden D.C. Hesseling. It was not the last: the most recent one is Peter Borghart’s Inleiding in de Nieuwgriekse literatuur (Introduction to Greek Literature), an excellent introduction to the history of Greek literature for Dutch-speaking audiences, of which a substantially revised edition has just been published. And there is of course the work of Wim Bakker and Arnold van Gemert—both former professors at the University of Amsterdam—on the Cretan literature of the early modern period and the Renaissance, which was seminal in the field of Modern Greek literature. The department of Modern Greek at the University of Amsterdam—at the moment, the only such department in the Benelux—has contributed greatly to scholarship in Modern Greek literature and history. We hope to extend this contribution towards the future, also through the newly founded Marilena Laskaridis Chair of Modern Greek studies. To that end, the Laskaridis Foundation, chief sponsor of the chair, has decided to sponsor a number of visiting fellowships per year for scholars from Greece and elsewhere wishing to do research in Modern Greek Studies at our university; the first call for applications will be announced this January.

There is of course a lot more happening beyond academia. Dutch translations of Modern Greek literatureabound thanks to remarkable translators. The most prolific one is Hero Hokwerda, who has given us so many excellent translations of Greek and Cypriot poetry and prose. A wonderful anthology of Modern Greek short stories also appeared in 2013, translated by my colleague in Amsterdam, Arthur Bot, and by Anna Dekker. Not to mention the many Greek artists and musicians who live in the Netherlands and are making a mark in the country’s artistic life. The composers Aspasia Nasopoulou and Calliope Tsoupaki are two great examples from the music scene. Calliope Tsoupaki, who has been living in Holland since the early nineties, has just been appointed “Composer Laureate” of the Netherlands for the next two years—not a small achievement!

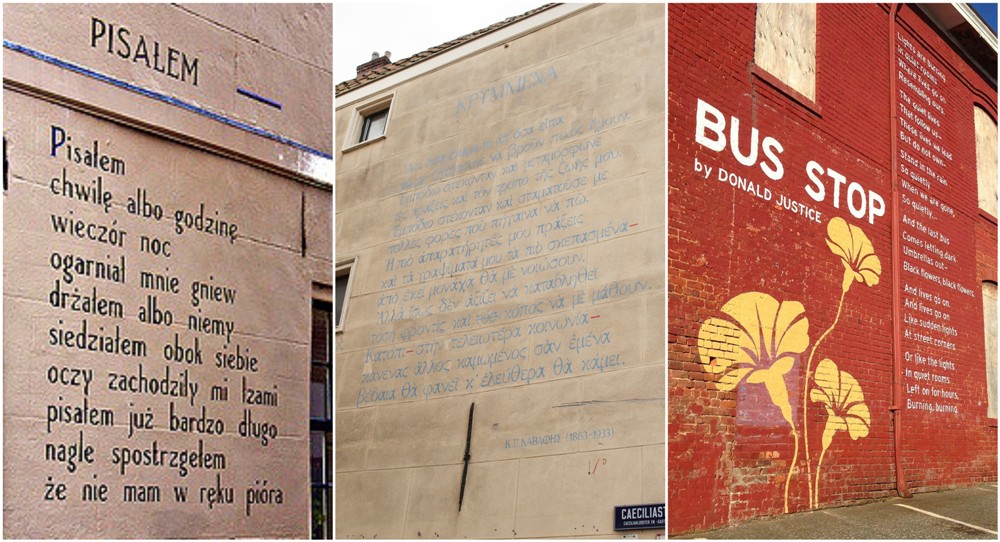

Wall poems in Leiden, Cavafy´s poem “Κρυμμένα” (“Hidden Things”) in the middle

Wall poems in Leiden, Cavafy´s poem “Κρυμμένα” (“Hidden Things”) in the middle

The recent shift in our curriculum has indeed foregrounded culture and history and de-emphasized the place of language and linguistics. Literature remains part of the program, although its presence is unfortunately less prominent than before. This change was the result of a decision taken by the Faculty Board and had to do with budget cuts that have affected not only Modern Greek but all departments of modern languages and cultures at the University. As a result, our program now includes more joint courses with other departments, placing Greek culture and history in transnational and transcultural frameworks: in Europe, the Mediterranean, the world. Greek culture and history are studied in comparative frameworks, and collaborations with other departments become indispensable. This may be a recent change for our department, but such approaches have of course been a reality for quite some time in other Modern Greek departments in the U.S. and some European universities.

Although this shift comes with certain losses and frustrations, we have to focus on the promising prospects it opens up and exploit them to the fullest. We already see this year that in joint courses, student numbers have increased significantly, allowing us to bring students of other programs in contact with Modern Greek culture and history; this is very important. Collaborative teaching and input from students with different backgrounds can make our program more dynamic and competitive but also help us probe blind spots and parochial attitudes in our respective fields. So, one of the challenges that come with our new curriculum is to engage audiences beyond Modern Greek studies: in comparative literature, cultural studies, European studies, philosophy, history etc.

I need to stress something here, however, that I consider crucial. Debates in Modern Greek studies often present a “cultural studies” approach as diametrically opposed to a “philological approach.” There is surely a gap between these approaches, and the way they materialize in the work of their practitioners often makes the gap seem unbridgeable. But seeing the approaches as such as incompatible can be limiting. Certain philological skills can be valuable tools we could offer our students when practicing what many call “cultural studies” and what I prefer to call “cultural analysis.” This a term proposed by my teacher and mentor, Mieke Bal, for an interdisciplinary research practice she developed in relation, but also in opposition, to “cultural studies.” “Cultural analysis” resists the tendency we sometimes trace in cultural studies to use cultural objects as illustrations of a pre-existing argument or theory or treat them superficially through generalizations. It requires attentive engagement with an object of study—be it a poem, artwork, film, or something else—through a close reading that often requires philological competencies as much as it unfolds in dialogue with theoretical concepts and with the contexts surrounding this object—both past and present.

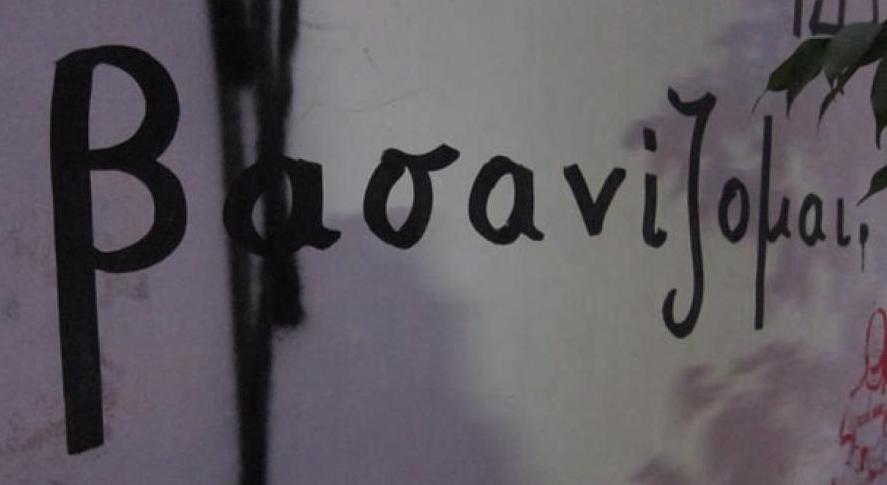

In fact, some of the most exhilarating moments in my research involved projects that reconfigured philological tools and categories and combined them with literary, political, and cultural theory. For example, an article I wrote in 2016, revolved around a popular Greek wall-writing, featuring the word βασανίζομαι (vasanizomai – I am in torment), which led me to develop a larger project on the workings of the “middle voice” (a grammatical voice in which the subject undergoes the action expressed by the verb) as a broader expressive modein contemporary Greek art, literature, and cinema. In this project, I ask whether (and under which conditions) the “middle voice” could help articulate alternative accounts of the present and of subjectivity, agency, and responsibility that deviate from dominant narratives of the Greek crisis.

So to return to the shift in our curriculum: this shift requires us to be even more attentive to the particularities of each object we engage with. Being part of an interdisciplinary field of Modern Greek studies with a broader appeal means that this field becomes much less delimited and more diffuse: and this means that with each research project, article or course we teach, we are called to form a new field on unstable ground. This is challenging, difficult, and exciting, and it may not always work optimally, but it can yield innovative results in teaching and research.

“Vasanizomai” wall-writing at Romvis street, Athens, 2014. Photograph by Maria Boletsi

“Vasanizomai” wall-writing at Romvis street, Athens, 2014. Photograph by Maria BoletsiThe crisis in Greece and the media attention it generated has increased global interest in all things Greek. The Greek arts scene has been said to have flourished during the crisis. Can this momentum be channeled to attract more students in Modern Greek Studies?

The cliché that art thrives in crisis-times is true in this case—at least in certain domains, such as cinema, public art, poetry, theater—despite limited financial means. The international attention this “cultural renaissance” (as some call it) has drawn is remarkable. A June 2018 article in the New York Times by Charly Wilder with the title “Athens Rising” casts the city as “emerging from the wreckage as one of Europe’s most vibrant and significant cultural capitals.” I have come across so many articles in the foreign press about the booming street art scene in Greece. Films by Yorgos Lanthimos, Athina Rachel-Tsangari, and other remarkable filmmakers—some associated with the so-called ‘Greek Weird Wave,’ despite their resistance to this label—have put Greek cinema in the international spotlight. Poetic anthologies of recent Greek poetry in translation—such as those by Karen van Dyck and Theodoros Chiotis—have reached broad English-speaking audiences. And there was of course Documenta 14 using Athens as its second city-venue: a major event, notwithstanding the controversy it sparked.

All this certainly creates an opportunity for attracting more students. Even outside of Modern Greek departments, foreign students are showing interest in what is happening in Greece. At the Film and Comparative Literature department in Leiden, where I have been teaching since 2010, two of our students just wrote their theses on recent Greek cinema and last semester another student wrote a brilliant paper on a short story by Christos Ikonomou. The way non-Greek students approach and theorize Greek cultural production is often extremely refreshing.

Sparking students’ interest in Greece requires structuring our courses around questions that make Greece and its culture part of transnational debates. Next semester, for example, I will teach a Master’s seminar in Amsterdam on “Crisis Rhetoric and Alternative Narratives in Literature, Art and Theory” in which we will scrutinize the Greek context of the crisis in relation to other Mediterranean crisis-scapes, through the languages of poetry, short stories, films, and street art, and guided by readings in literary and cultural theory, anthropology, and conceptual history. The response has been encouraging so far: the seminar is full and has a waiting list.

So, there is surely a momentum for shaping a critical field of Modern Greek studies that addresses students or scholars with no exclusive interest in things Greek. As other colleagues have also stressed, including Dimitris Papanikolaou in his interview for Rethinking Greece, this is already happening: scholars around the world working on topics related to modern Greece are creating platforms that have energized critical debates on Greece, essentially redefining the field of Modern Greek studies. So despite the shrinking of Modern Greek departments abroad, there is new energy, partly owing to promising young scholars. And we cannot forget of course that much innovative scholarship on Greece is being produced by scholars in other departments—anthropology, history, sociology, comparative literature, archeology etc. Using this momentum, we can turn the ‘islands’ of our Modern Greek and other departments into dynamic networks—or archipelagos.

C. P. Cavafy has been a constant reference point in yours and in the work of other Modern Greek Studies researchers and academics. In what terms is Cavafy’s oeuvre relevant in the current conjecture?

Cavafy’s poems keep returning like specters, claiming, and being claimed by, our present and its desires and anxieties. To me—and so many others—these poems have been constant partners in thinking, not just texts I study and love. They are epistemological and affective machines that have guided the ways I read and experience other texts and objects. And they have been that for so many people and communities: ‘tools’ for thinking our relation to the past and the future, understanding the self and its others, the self in relation to the social and for rethinking or imagining communities.

In a book I am writing on Cavafy, I broach the question of his relevance in the present through the concept of haunting, by exploring what I call his poetics of the spectral: poetic strategies for conjuring the past and making past moments, people, or objects—including the poems themselves—active forces in future presents. I trace the spectral as a central conceptual metaphor in Cavafy’s modernist poetics but also as a lens that helps us account for his poetry’s bearing on our present, from post-Cold War realities in the West to contemporary Greece.

One of his poems with a powerful bearing on our present is “In A Large Greek Colony, 200 B.C.” (“Εν μεγάλη Eλληνική αποικία, 200 π.Χ.”): the poem stages a present of stifling crisis, in which the future of a colony is outlined by the speaker as a binary choice: either violent external reform or preservation of the status quo. In my book, I read the poem as posing a challenge: how to create space in language for hope and justice even when a framework of crisis imposes the seeming necessity of dualistic choices. In other words, how does the poem foster a space for alternative, unpredictable futures, beyond the limited probabilities that govern its colony’s present? A very topical question in Greece today.

Cavafy haunts, also because his poetry is deeply concerned with haunting. Haunting in Cavafy translates into strategies of conjuring the past and resisting death and finality, without, however, appealing to eternal life or the permanence of poetic truth, language or history. Cavafy’s poetry could actually be seen as a response to the same question that returns in many guises: What are the conditions that make the dead return in our present, albeit temporarily? This includes his own poems: How can one make poems that come alive in future presents? Deeply aware of loss and death, Cavafy tests ways of animating the past in the present through poetry. He knows there is no magic potion for eternal life, and if it did, that would be boring. “[S]peech is condemned” when it remains invulnerable to time, Cavafy wrote in an early essay known as “Philosophical Scrutiny” (1903), as “things cannot and should not be lasting.” No truth or perspective is safe in his universe; presences are fleeting, spectral, threatening to dissipate, but this precariousness makes his writing all the more capable of haunting future presents unpredictably.

Using Cavafy’s poem “Waiting for the Barbarians” as a starting point you have explored the concept of barbarism in European History. Would you like to expand on that?

Cavafy´s poem “Waiting for the barbarians” is a striking example of the contemporary afterlives of his poetry I was talking about before; a poem with a haunting presence in the Western cultural and political imaginary, regularly evoked by journalists, politicians, scholars, and other authors as an allegory for post-Cold War realities and current political and cultural crises.

When I was writing a paper about this poem for my Master’s degree, I started noticing the term “barbarian” everywhere in the press, in political speeches, in the media. These were the first years after the attacks on ‘9/11’ and during the ‘war on terror,’ which led to a dynamic comeback of the rhetoric of ‘civilization versus barbarism’ in the West. So I took this as a starting point for developing a doctoral project around barbarism, in which Cavafy’s poem and its international travels in literature and art had a prominent part.

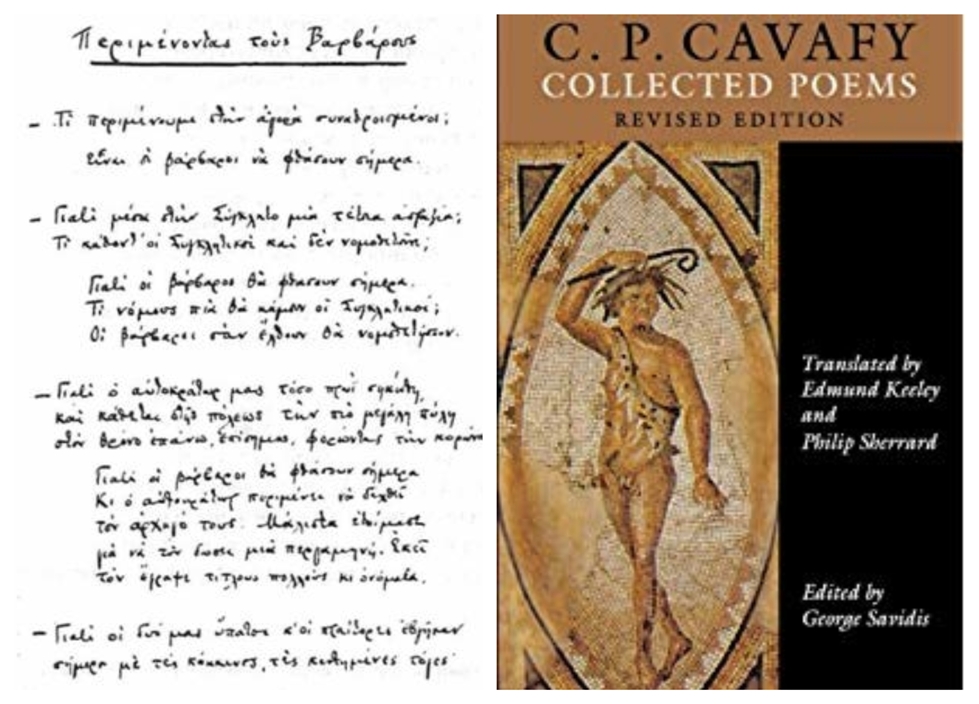

“Waiting for the Barbarians” manuscript and C. P. Cavafy’s Collected Poems Princeton University Press; Revised edition (1992)

“Waiting for the Barbarians” manuscript and C. P. Cavafy’s Collected Poems Princeton University Press; Revised edition (1992)Today, the rhetoric of ‘civilization versus barbarism’ shows no signs of waning: it is intensely mobilized by populist politics, by the alt right, but also by mainstream politicians, most notably in responses to terrorism and the ‘refugee crisis.’ Politicians and journalists regularly tap into the narrative of ‘barbarian invasions’—e.g., in reactions to the refugee situation—forging simplistic analogies between the present and the Roman Empire. Such analogies, which create the impression that history repeats itself, have pervasive consequences for how we perceive others. For example, I recently looked into uses of the term ‘barbarian’ in international responses by politicians, officials, and organizations to terrorist attacks in Europe and the U.S. in the last few years. What stood out was that “barbarism” or “barbarian” were extremely popular for referring to terrorist acts by Muslim perpetrators, but when the perpetrator was white, the term “barbarian” was completely absent: the latter perpetrators are usually cast as “lone wolves,” “confused kids, “mentally disturbed” etc. Using the term “barbarian” for Muslim perpetrators enables their identification with a whole culture that is considered external to the West. By contrast, framing ‘white terrorists’ as deviant individuals de-culturalizes their acts: it casts them as exceptional deviations from the spirit of Western civilization rather than linked to systemic conditions.

This shows how powerful words can be in shaping our realities. So exploring the European history of ‘barbarism’ is crucial for a critical understanding of its contemporary workings. The ‘barbarian’ is central in the European imaginary since Greek antiquity, so its history is also a history of the shifting contours of European identity. This has been the focus of the collaborative project Barbarian: Explorations of a Western Concept in Μodern Theory, Literature and the Arts, the first volume of which was just published by Metzler in 2018; with scholars from Germany and Switzerland (and, recently, England too), we are researching the concept’s modern European history with an emphasis on the role of literature in its changing functions. In a chapter I wrote for this book, I returned to Cavafy’s poem, to trace how it converses with the ‘barbarian’ figure in European literature and how it relates to philosophies of history and the concept of crisis. I probably haven’t devoted more pages to any other literary work than this poem. So I am inclined to say that now I am done writing about it—but you never know!

Some theorists claim that Greek “crisis art” is a form of self-exoticizing. Do you believe Greek art/literature has become overly politicized? Is there a way to rethink Greece and challenge post-colonial narratives on the crisis and “crisis art”?

Much of the international attention recent Greek art has been receiving is in one way or another framed by reference to the ‘crisis.’ So scrutinizing the popular frame of ‘crisis art’ and being attentive to the (self-)exoticizing tendencies that often pervade it is necessary. The tendency to reduce artistic forms of expression in Greece to by-products of the ‘crisis’ risks turning crisis into a master-narrative that appropriates cultural products and often determines their reception in restrictive ways.

That said, disavowing the politicization of Greek art is not really an option. We cannot deny that Greek artistic and literary works operate within, and often intervene in, the Greek sociopolitical landscape as shaped through the crisis, and thus relate to it, regardless of their makers’ intentions. What we could do, then, to resist ‘crisis’ as a reductive master-narrative for art is, first, probe crisis itself. Crisis is never just a descriptive designation but a discursive and experiential framework with profound consequences: a framework that privileges and legitimizes particular narratives of the present while precluding others. Although the term crisis in ancient Greek denoted ‘choice,’ ‘judgment,’ and ‘decision,’ the framework of crisis today often works to limit the space of choice in politics (think, for example, of how austerity politics were cast as a ‘one way street’) and the imagination of alternative futures. Resisting this framework, artists, filmmakers, and literary authors in Greece have been concerned with forging new imaginaries and alternative ‘languages’: modes of speaking, looking or relating to others that challenge ‘crisis’ as a master narrative and prompt new, sometimes radical ways of engaging with the (Greek) past as part of the present and the future. Engaging with such alternative ‘languages’ and modes of expression takes center stage in my current work as well as in our research group on ‘Crisis, Critique, and Futurity,’ which I have initiated in the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA) together with Eva Fotiadi.

So without necessarily thematizing or addressing the ‘crisis’ explicitly, art and literature can be political in a more profound way: by intervening in what Jacques Rancière calls the “distribution of the sensible” or by reconfiguring what Cornelius Castoriadis described as a society’s “instituted imaginary.” Many fascinating works of art, literature, and cinema in recent years try to do just that, and such works deserve our attention for their political thrust. To resist exoticizing, reductive, or colonially inflected frameworks for the reception of such works we need to approach them not just as objects symptomatic of certain sociopolitical conditions, but as agents of what Arjun Appadurai calls a “politics of possibility”: a politics that opens up the present and the future to modes of being and thinking we cannot fully calculate or predict based on existing frameworks. This seems essential for thinking Greece beyond the framework of crisis.

Read more on Modern Greek Studies via Greek News Agenda:

- Dimitris Papanikolaou on Greek exceptionalism and the “Holy Greek family”

- Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek

- Vassilis Lambropoulos on New Greek Poetry and Modern Greek Studies

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | RESEARCH