Nicholas J. Cull is Professor of Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication, where he directs the Masters Program in Public Diplomacy. His research and teaching interests are inter-disciplinary, and focus on public diplomacy and -more broadly- the role of media, culture and propaganda in international history.

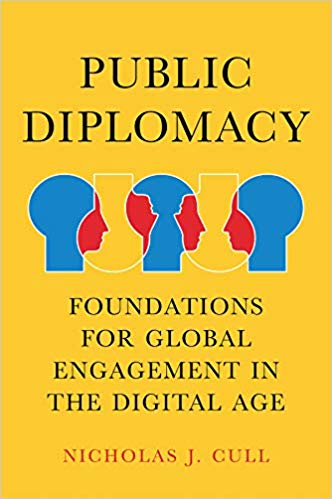

He is a prolific author and his volume on the history of US public diplomacy: The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989 (Cambridge 2008) was named by Choice Magazine as one of the Outstanding Academic Texts of 2009. He has also published, on the same subject, the book: The Decline and Fall of the United States Information Agency: American Public Diplomacy, 1989-2001(Palgrave, New York, 2012). He has published numerous articles on the theme of propaganda and media history. His most recent book is “Public Diplomacy: Foundations for Global Engagement in the Digital Age” (Polity, 2019). He is a former editor of the journal Place Branding and Public Diplomacy; past president of the International Association for Media and History, and a current board member of the Public Diplomacy Council of Washington DC.

Last November Nicholas Cull travelled to Greece to participate in the 4th Annual Conference of the International Place Branding Association organized in Volos (November 27-29) with the collaboration of the University of Thessaly, where he spoke about nation branding and public diplomacy. The event brought together branding experts from academia, practice and policy making for a valuable discussion around the intersection of marketing, tourism, economic development, events organization, heritage management, spatial design, public diplomacy and human geography.

Professor Cull spoke to Greek News Agenda* about the relationship between image and reality in nation branding analyzing the term Reputational Security. He also put emphasis on the public dimension of diplomacy as people are nowadays central to international affairs and global politics because of technological changes, underlining at the same time the importance of evaluating digital media content. Concerning Greece’s efforts to enhance its image Cull suggests that the country needs to listen to understand its strengths and its vulnerabilities in international opinion having though the unique advantage of people’s pre-existing emotional connection to its ancient world.

In your presentation at the IPBA Conference in Volos, you talked about the role of place and nation branding in building and preserving what you have termed Reputational Security. Could you elaborate on that?

My argument is that developing and preserving a positive reputation is not a side issue for a nation state but rather it is part of the core functions and duty: protecting its people. Nations that are known and liked around the world have a palpable hedge against others intruding against their interests. A team from the University of Edinburgh recently showed that there is even a correlation between the level of a country’s international cultural activity and its ability to win votes in the UN General Assembly. Personally, I question the claim that the marketing processes associated with Nation Branding can achieve much on their own but I think that the process of considering a reputation systematically can certainly be an invaluable mechanism for directing attention to the underlying realities. The bottom line is that if you want a better image you should build a better reality, and be relevant to the audience you wish to impress.

In your opinion, why is Public Diplomacy important to nations and states and how is it related to traditional Diplomacy?

Public Diplomacy has always been practiced and appreciated by the wisest leaders. In my most recent book I am able to show examples from Greek antiquity. I identify five core practices: listening, advocacy, Cultural diplomacy, exchange and state-sponsored news which many wise rulers practiced because they understood that the feeling of people underpinned the international actions of the nation state. The difference today is that because of political and technological changes the people are now central to international affairs. All diplomacy has a public dimension and in fact the public are necessarily the final arbiters of global politics; that is why there is so much scrambling right now to capture their attention and, arguably, to keep them divided.

Yiannis Moralis: Sketch for ceramic mural for the Athens Town Hall (1985) – Source nikias.gr

Greece, having overcome a severe economic crisis, is trying to reposition and reintroduce itself to the global community as a land of creativity, innovation and sustainability, leaving behind the prevailing images of recession and austerity. In your opinion, what should Greece do or not do in order to succeed in enhancing its image?

The first thing that every initiative in public diplomacy must begin with is listening. Greece needs to listen to understand its strengths and its vulnerabilities in international opinion. We know that reputations change quickly so the government may be frustrated to find that many international ideas are out of date. This can work in your favour when outside perception is slow to pick up on failings with seem obvious to residents. The US and UK both are seen rather more favorably overseas than many at home would expect. One of the unique advantages of Greece is the pre-existing emotional connection which people have to its places: the site of Olympus or Thermopylae. It seems as astonishing to see these on road signs as it would be to see signs for places in Lord of the Rings or Star Wars. Yet Greece has often done little to take advantage of the link between the inner-mental place and the real world location on Greek territory. At the Volos conference several of the delegates, myself included, described the same experience. We came to Greece keen to see a place we knew from ancient history — for me it was the Pnyx, another wanted to visit the site of Plato’s Academy; another places associated with Hippocrates the father of medicine — and found nothing special there. Greece has done more for the Gods we’ve outgrown than the mortal concepts we are still working with, and I wonder if there is a way to invite the world to share in the memorialization and further perpetuation of those ideas.

In your latest book “Public Diplomacy: Foundations for Global Engagement in a Digital Age”, you explain how the advent of digital and social media has changed the landscape of cultural diplomacy. Could you provide some examples?

I wrote my book to show that even though we live in a digital world, the underlying principles of public and cultural diplomacy remain, and what worked in the past — listening first; crafting a message with an eye to its shareability; maintaining your own credibility — remain the core to successful public engagement. Yet there are important changes. The worst ideas in the world are no longer limited by geography. Extremists are able to connect with each other. The most disruptive ideas — such as xenophobia, emphasis on one’s own victimhood; cynicism about allies and events — circulate with little restraint among people still ill-equipped to evaluate them. I feel we have a vested interest in helping audiences to evaluate the media of our age; in empowering the voices working to make the world a better place and working together to build a context in which trust can develop. I would like to see less emphasis on the digital as a mechanism of broadcasting and more on it as a forum for mutual engagement and collaboration. We have only just begun to see its potential for such work.

* Interview by Ioulia Elmatzoglou

TAGS: HERITAGE | HISTORY | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | MEDIA