Nikos Papatakis (1918-2010) was an Ethiopian-born Greek filmmaker, renowned for his subversive and provocative works. Startling, subversive, and explosively controversial, the films of iconoclast Nico Papatakis have long been frustratingly hard to see, but they constitute one of the most radical and neglected bodies of work in all of European cinema. His 1967 film, The Sheperds of Calamity, is renowned director Yorgos Lanthimos’ all-time favorite film,

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on July 19, 1918, to a Greek father and an Ethiopean mother, Papatakis spent his early years between Ethiopia and Greece. At 17, he joined Haile Selassie’s army to resist the fascist Italian invasion of Ethiopia. After After the defeat by Benito Mussolini’s forces, he was driven into exile, first in Libya and then Greece, before finally settling in Paris in 1939.

In Paris, Papatakis initially worked as an extra in films and eventually owned the famous nightclub La Rose Rouge, a hub for intellectuals and artists. Performers like Juliette Gréco made their debuts there, while luminaries such as André Breton, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Boris Vian were regular patrons. During this time, Papatakis befriended Jean Genet, who dedicated his poem “La Galère” to him, “Nico, the Greco-Ethiopian God.” Their friendship was tumultuous, marked by both collaboration and conflict.

In 1950, Papatakis funded and provided the location for Genet’s film Un Chant d’Amour, which, due to its explicit content, was banned but later circulated as contraband. After a three-year marriage to the actor Anouk Aimée, with whom he had a daughter, Manuela, Papatakis left for New York, in disgust at France’s colonial war in Algeria 1957. There, Papatakis got to know the actor John Cassavetes, and co-produce with him Shadows (1959), Cassavetes first film as director.

While in New York, Papatakis had an affair with the German-born model and singer Christa Päffgen, who took the professional name of Nico from her lover. Papatakis would meet Päffgen near the start of the 1960s, On a lark he asked her if she had ever considered a career as a musician, and so it happened that Papatakis ended up enrolling Nico in her first singing lessons, which eventually led to her performing with the Velvet Underground.

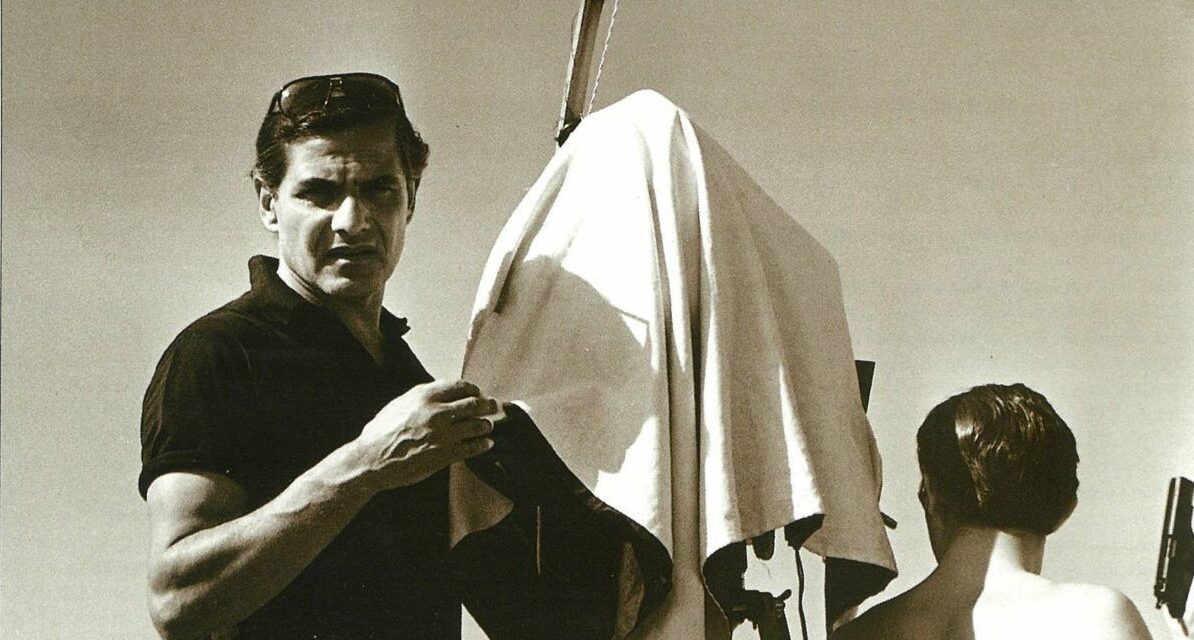

When he returned to Paris after the Algerian War, Papatakis decided to try his own hand at filmmaking, with Les Abysses (1963), an adaptation of Genet’s 1947 play, The Maids. Both The Maids and Les Abysses dramatize the lurid story of the Papin sisters, servants who murdered their employers in the 1930s. Papatakis submitted Les Abysses to the Cannes Film Festival and the selection committee boycotted it, but after Sartre and de Beauvoir lobbied on his behalf the festival eventually screened the film to uproarious scandal.

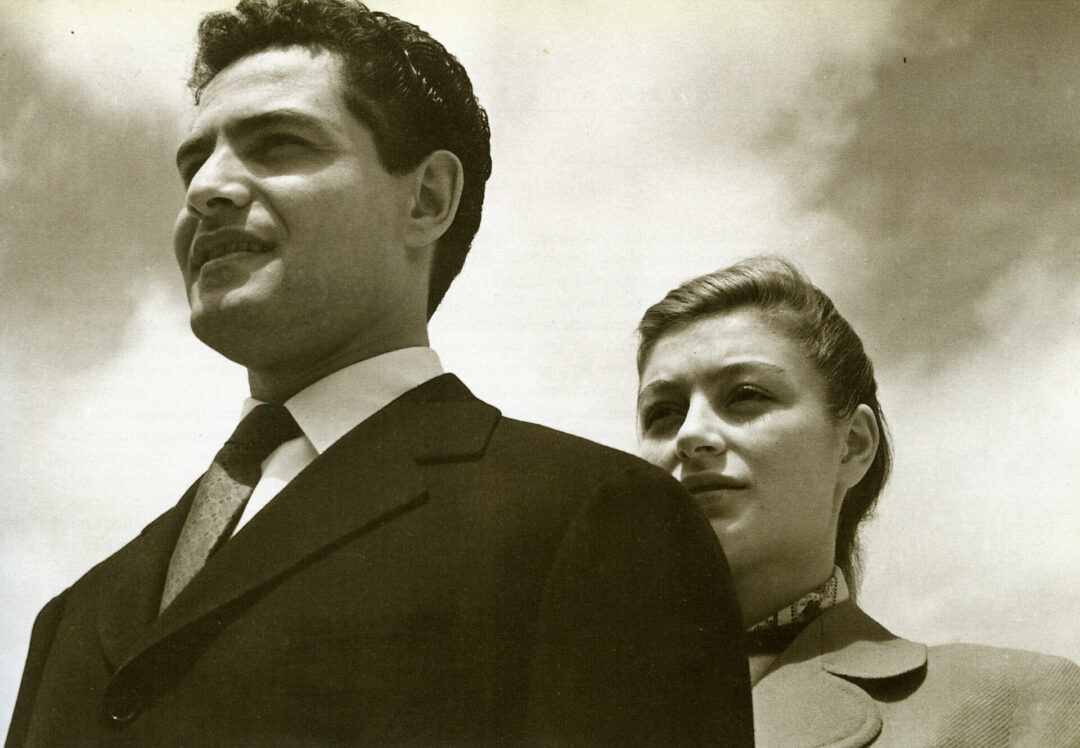

His subsequent works continued to challenge social and political norms. Papatakis returned to filmmaking a few years later in Greece with Thanos and Despina (1967), also known as Shepherds of Calamity or The Shepherds, a tragic love story set against the backdrop of the Greek military junta. It starred his second wife, Greek actor Olga Karlatos, with whom he was active in campaigning against the regime of the Greek colonels.

Tim Markatos writes for Commonweal magazine: “Shot in striking black and white, Thanos and Despina is clearly a more refined film than Les Abysses in nearly every regard, the manic energy of that freshman film still intact but doled out in smaller doses. Papatakis made the film the same year the Greek military overthrew the government, though you’d be forgiven for assuming this tale of creeping authoritarianism must have been shot after the fact. […] It is rare to find a movie that engages with Eastern Orthodoxy as directly as Thanos and Despina does, and rarer still to find one set entirely between Holy Saturday and Pascha, the holiest forty-eight hours in the Orthodox liturgical year ” It starred his second wife, Olga Karlatos, with whom he was active in campaigning against the regime of the Greek colonels.”

According to four time Academy Award nominated filmmaker Yogos Lanthimos, The Shepherds Of Calamity is “definitely one of the greatest Greek films ever made.” Similar to Lanthimos’ own work, this classic film takes a simple plot and makes it strange. It tells the story of a poor farmer trying to marry her son to the daughter of a rich land owner, but through director Nico Papatakis’ eye, it becomes something bigger and weirder. “I could have never imagined something so modern, absurd, anarchistic set in a bucolic environment and made in Greece during the ’60s,” Lanthimos said of the movie. “ I’m always taken by surprise when I re-watch it.”

Gloria Mundi (1975), was a disturbing drama starring Olga Karlatos as an actor who plays an Algerian terrorist in a film directed by her husband, but who has to face degradation and torture in reality because of her belief in a revolutionary ideal. It was withdrawn when the extreme right threatened to plant bombs in the cinemas where it was showing, and had to wait until 2005 to be screened publicly again in Paris.

Papatakis’ films are noted for their intense, expressionistic style and themes of power, revolution, and social upheaval. His last two films, I Photografia (The Photograph, 1987) and Walking a Tightrope (1992), further explored these motifs: The Photograph, in which an emigrant from the military dictatorship in Greece goes to Paris, was a fairly potent political allegory. According to the critic Yannis Kontaxopoulos, Papatakis’s oeuvre “revolves around one single theme: the relations between master and slave, humiliation and revolution, on both a political and personal level”. His last film, Walking a Tightrope, dealt with a famous gay writer who tries to make the young Arab boy he loves into the world’s greatest tightrope walker. The main character, played by Michel Piccoli, was a thinly disguised version of Genet.

Nikos Papatakis passed away on December 17, 2010, leaving behind a legacy of films with expressionistically heightened style and transgressive themes. His radical and influential cinema that inspired contemporary Greek filmmakers like Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari. Despite his films’ initial obscurity – his five films were difficult to track down in English until they were restored in 2018 for a brief theatrical run in New York City – they are now accessible to new audiences, via various streaming platforms, solidifying his place in the pantheon of groundbreaking European directors.

According film critic Tim Maratos, “Papatakis would never enjoy such success in his lifetime, but it was never his intention as a filmmaker to look for it. Despite his proximity to wealth and celebrity, Papatakis’s firsthand experiences of fascism, war, poverty, and exile seem to have kept him from ever turning his desire to unsettle the audience into a brand or a means of securing funding for his next project.”

In a featurette shot for the Criterion retrospective on Papatakis, Athina Rachel Tsangari recalls some foreboding advice Papatakis passed down to her at the start of her career: “Don’t try to imitate life. You’re a descendant of Euripides and Aeschylus—it’s all about creating this archetypal violence. Make the audience uncomfortable!”

I.L., with information from the Guardian, Criterion, Commonweal Magazine and Farout Magazine.

TAGS: ARTS | cinema | GLOBAL GREEKS | GREEK FILMS