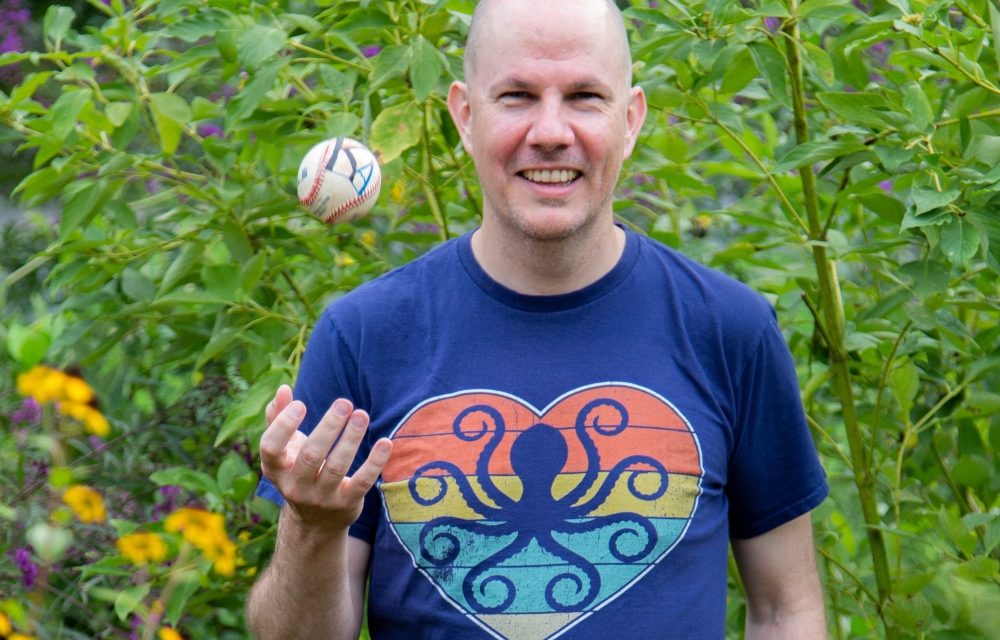

Norman Sandridge is Associate Professor of Classics at Howard University. He began his academic career at the University of Alabama in Huntsville with an undergraduate major in Physics and a minor in Mathematics. He was chosen best physics student by the physics department in his junior and senior years. He was also the president of the Society for Ancient Languages in his senior year and was awarded best leader of an undergraduate academic organization. Dr Sandridge earned an MA in Latin at Florida State University and was awarded the Rankin Prize there. He then earned an MA in Ancient Greek and a PhD in Classics at the University of North Carolina. He has been an ongoing fellow at Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies since 2012.

Dr. Sandridge is a co-founder of Kallion Leadership, an organization devoted to the study of leadership and the training of leaders through the humanities. His research has focused on ancient leadership, including leadership and the emotions, ideal leadership, the process of becoming a leader, and leadership and the contemporary construct of psychopathy. Much of his work relies on the use of digital humanities.

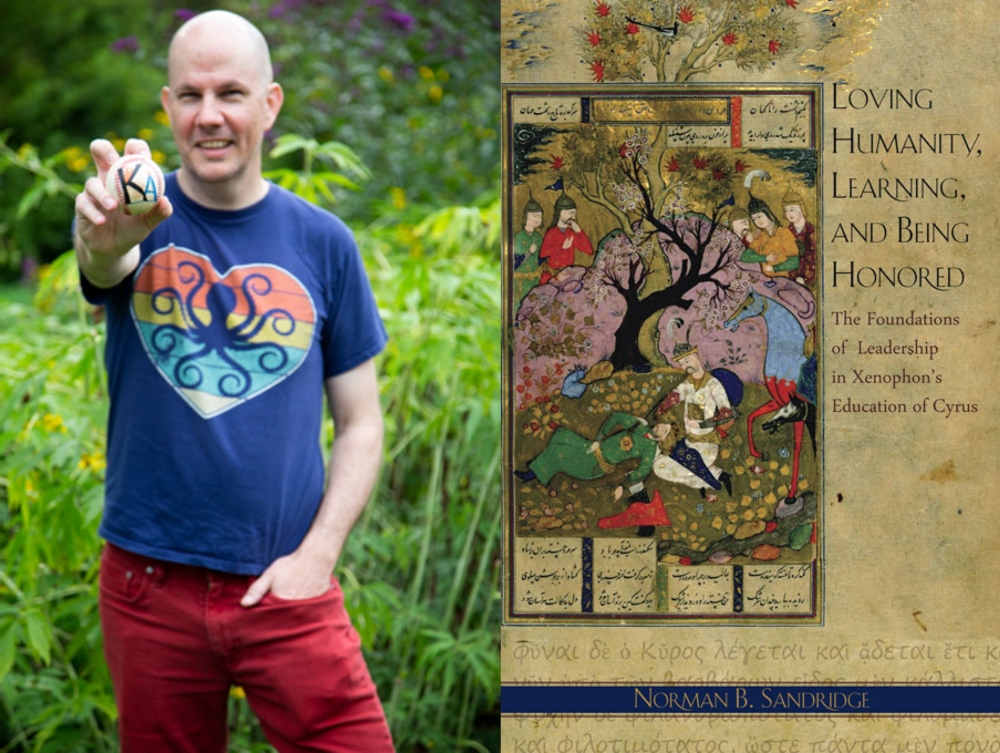

In 2012 he published a book entitled Loving Humanity, Learning, and Being Honored: The Foundations of Leadership in Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus. Currently, Dr. Sandridge is co-editing the Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Greco-Roman Leadership with Dr. Sarah Ferrario and co-editing with Dr. Mallory Monaco Caterine a SAGE series of business case studies on “Becoming a Leader in the Ancient World”.

With the aid of the Public Diplomacy Office at the Embassy of Greece in the USA, Greek News Agenda interviewed* Dr Norman Sandridge on the place of classics in the modern world, the ways in which ancient thinkers can still shape the notion of leadership in contemporary societies, and how these are explored through modern research, including the activities of Kallion organization.

You started off in STEM but then earned two MAs in Latin and Greek and a PhD in Classics. How did the humanities win you over – and was this in spite or perhaps because of your earlier academic career in sciences?

You started off in STEM but then earned two MAs in Latin and Greek and a PhD in Classics. How did the humanities win you over – and was this in spite or perhaps because of your earlier academic career in sciences?

There are two answers to this question. First, I was fortunate to have several important mentors in my academic journey at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, including my philosophy professor, Dr. Brian Martine, my English professor, Dr. Jeff Nelson, and most of all my Latin professor, Dr. Richard Gerberding, who not only built a castle in northern Alabama (yes, a castle) but also introduced me to the study of ancient languages and guided me in my application to graduate school. Secondly, yes, my interest in ancient languages, at least at first, was very scientific, in the sense that I loved learning the rules of Latin and Greek grammar, memorizing hundreds of forms, and being able to comprehend how the meanings of words logically evolved over time in metaphorical ways. I remember learning in one of my first Latin classes that the word pecuniary, which in English means “relating to money”, originally came from the Latin pecus, which means a flock of cattle. It comes to mean money because money is movable wealth and so are cattle!

Your approach to the Classics is a rather innovative, especially with regard to your focus on leadership theory. What can the ancient philosophers teach us about leadership in our complex, ever-evolving modern world?

Ancient thinkers and historical figures teach us so much about leadership, probably first and foremost that leadership is a vastly complex and fascinating phenomenon. For me it was the study of ethics, particularly in ancient epic and tragic poetry, that first drew me to think about leadership. Many of the ethical problems in these works are posed to figures in leadership roles, characters who must decide not only what is best for themselves but also their families, friends, and fellow-citizens. Things like wealth, honor, responsibility, and accountability all make ethics more interesting and these are also typical trappings of leadership. Anyone who hopes to lead today should be aware of these factors from the outset and develop at least some ideas for how to manage them.

Tell us about Kallion Leadership, the non-profit organization of which you are co-founder and Co-Executive Director, and aims to promote leadership development through the study of humanities.

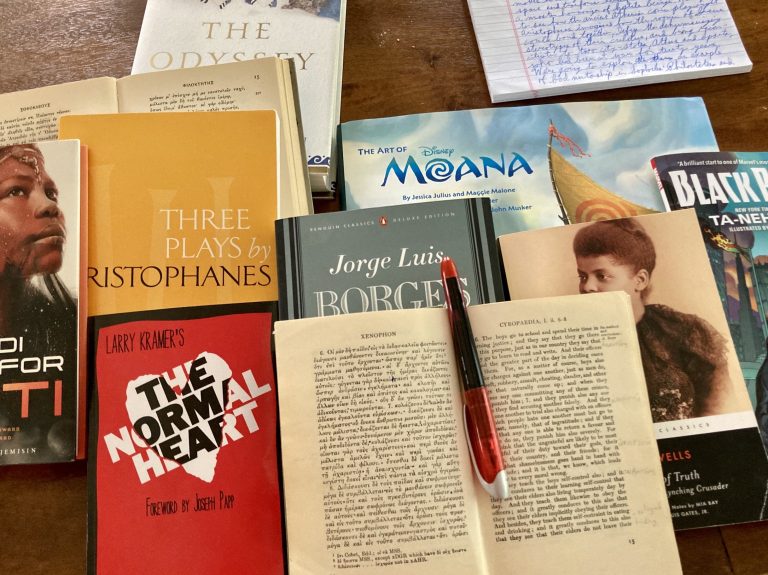

Kallion treats leadership as the art of meeting the needs of other people in individual, group, and institutional settings, a definition we have paraphrased from the ancient Athenian author Xenophon in the Education of Cyrus (1.6.7). We believe that leadership exists in everyone and that delving deep into the humanities is the best way to activate this capacity in a comprehensive way. Specifically, we believe that studying the humanities gives us greater appreciation for what leadership is, it offers us numerous leadership behaviors to contemplate and emulate, and it can help us find more collaborative relationships with others, make better decisions, and improve how others see us and how we see ourselves. We have communities within Kallion that focus on research, leadership training for humanities educators, and leadership development communities outside higher education composed of professionals who want to engage in ongoing leadership development. Kallion also focuses on democratic leadership as a core part of our identity. This summer we are hosting our third annual International Camp for Democratic Leadership online.

Kallion’s name comes from the ancient Greek adjective kalos, which can mean “good”, “fine”, “noble”, or “beautiful”. Kallion is the comparative adjective, which “better”. (Image on the left taken from Kallion.org [courtesy of Jenny Bick])

Kallion’s name comes from the ancient Greek adjective kalos, which can mean “good”, “fine”, “noble”, or “beautiful”. Kallion is the comparative adjective, which “better”. (Image on the left taken from Kallion.org [courtesy of Jenny Bick])

Tell us more about the International Camp for Democratic Leadership (ICDL); how is the study of classics applied in it?

The International Camp for Democratic Leadership is an annual event arising from our partnership with fellow educators in Greece, with the goal of strengthening global leadership one individual at a time. Our guiding assumption is that, in order for a democracy to work, its citizens must have the ability to see and respect the full humanity of each other. One of Kallion’s advisors, Congressman Jamie Raskin, describes democracy as a form of government that “we all take care of together”. Kallion thus promotes forms of leadership that help others take care of their democracy. Our camp is made up of workshops that focus on leadership behaviors like introspection, building trust, and avoiding vanity. We also look at things like the role of drama (comedy and tragedy), rhetoric, and history in a healthy democracy. Our facilitators bring many different cultural backgrounds and educational experiences (including the ancient Greek world), to ensure that we are always able to think with the totality of what it means to be human.

You have published the monograph Loving Humanity, Learning, and Being Honored: The Foundations of Leadership in Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus, while you are also one of the primary collaborators on Cyrus’ Paradise, the world’s first comprehensive, online, communal commentary for a Classical text: Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus (Cyropaedia). What is it that makes this text so important?

Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus, written around 365 BCE, is a highly fictionalized account of the life of a historical figure, Cyrus the Second (or “the Great”), who loomed very large, both intellectually and materially, over much of the ancient Mediterranean and Near Easter world. Cyrus was the founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire which lasted until the time of Alexander (“the Great”) of Macedonia, a period of over 200 years. Xenophon’s quasi-biography of Cyrus was highly influential in Xenophon’s own time (it was seen as a response to Plato’s depiction of the Philosopher King in the Republic), in the time of Alexander (who styled himself as a second Cyrus), and in later Roman times: Julius Caesar was said to have been reading a copy of the work on the days leading up to his assassination and reflecting on the best way to die. The work has been treasured by many over the years, both during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment periods in Europe. It was read by several of the Framers of the US Constitution, and Thomas Jefferson had two copies (in ancient Greek!) in his personal library. In the 20th century it was recommended by the eminent researcher on business management theory, Peter Drucker, as the best book on the subject. I enjoy the Education of Cyrus for many reasons, including its exploration of what it truly means to be a lover of learning (philomathēs), a lover of honor (philotimos), and a lover of humanity (philanthrōpos). These questions are of course taken up by many later authors (and even some before), but Xenophon’s lively descriptions of Cyrus as a boy and then as the elder wise king at the end of a legendary career provide me with endless fascination and reflection.

Taking into account your STEM background, what are your thoughts on the disregard for the humanities often expressed (overtly or silently) by younger people with academic or work careers in the STEM or business sectors?

Taking into account your STEM background, what are your thoughts on the disregard for the humanities often expressed (overtly or silently) by younger people with academic or work careers in the STEM or business sectors?

Another ancient work I like from Xenophon is a short dialogue called the Hieron. It’s about a fictionalized encounter between Hieron, a famous tyrant from the town of Syracuse in Sicily, and the poet Simonides of Ceos. The dialogue is sparked by the fact that Hieron has lived his life both as a private citizen and as a tyrant, and Simonides wants to know which of the two lives is the happier one. Well, I have never lived my life as a tyrant, but I have lived my life as a scientist and as a researcher in the humanities, and I can tell you that we all need both. Moreover, I really don’t like it when people say “I’m not a science person” or “I’m not a music person” because I feel like these kinds of identities sell us short. We should pursue –and we should have the opportunity and encouragement to pursue– all of these identities even if they won’t become our life’s profession. I’m terrible at the guitar, but it brings me great catharsis and clarity!

As far as the disregard for the humanities goes, I think we are paying for that shortsightedness individually and collectively. Speaking for myself, I can say that studying the humanities since my days in college, and even before that, has given me much more clarity about my own thoughts and feelings about the world and the tools to express that to other people. It has also enabled me to take that most important of all journeys, the journey into the minds of others, which Odysseus took so many times in his trip homeward to Ithaca. The leadership abilities that the humanities has helped me cultivate have enabled me to connect better with my students at Howard University (who come from all over the country and all over the world) and to do things like co-found Kallion, an organization made up of people from countless different backgrounds and leadership roles.

The Classics’ value in the contemporary society has come under increasing scrutiny, and recently the very concept of “Classics” is challenged. What is your take on this contentious issue?

This question deserves a lot more space than we have time for here. But I will give you some of my shorthand ways of answering it. I rarely use the term “classics” anymore to describe my chosen field of graduate study, which is the languages and literature of the ancient Greco-Roman world. I don’t think the word “classic” is very helpful or accurate in most conversations; “influential” may be better. To me, how you read and that you read are as at least as important as what you read. In Kallion we promote the practice of reading in diverse communities and “building your own canon” of books and other works of art that have shaped who you are and continue to guide you. It’s important to have works like that and it’s important to share those works with others, even in an evangelical spirit (“You must read this! It’s so awesome!”). But it’s also important to realize that these works may be less relevant to other people than they are to you and that you yourself might outgrow them over time. In my early twenties I used to live by the fictional works of Ayn Rand; now they mostly seem naive and narcissistic to me. We don’t need to figure out exactly what books a young person should read over the course of their brief college careers. We need to set them up to be citizens of the world–true cosmopolitans– who are committed to reading about the thoughts and experiences of human cultures for their entire lives.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Also watch: Dr. Sandridge explains the meaning of the word “philanthropy”, as part of the series “The Greek Word of the Month”, a digital initiative by the Embassy of Greece in the USA.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Dr Rebecca Flemming, first A. G. Leventis Chair in Ancient Greek Scientific and Technological Thought; Beyond Socrates – Greek philosophers you might not know; Professor Michael Scott: By studying the ancient Greeks we learn more about ourselves