art by Mali Skotheim

By Johanna Hanink*

Virginia Woolf’s essay “On Not Knowing Greek” was published in 1925, the same year as Mrs Dalloway. The title gestures not to Woolf’s (nor to anyone’s) ignorance of Ancient Greek syntax, morphology and vocabulary, but to the impossibility of knowing today “how the words sounded, or where precisely we ought to laugh, or how the actors acted.” The essay is nevertheless an encomium of ancient Greek thought and literature, and, ironically, a testament to Woolf’s own fine command of the ancient language.

I think of it sometimes when I reflect on two frustrations I have about “not knowing” Modern Greek: a version of Greek in which you can, in fact, hear words, laugh on cue, and watch actors act. The first is with myself, because I wish I knew the language better. The second is with the field of Classics, for not institutionally valuing—and for even dismissing—any aspiring classicist’s efforts to learn it. After all, the thinking goes, those hours would be better spent on Homer and Thucydides (or even “German for Reading”: leave it to us to kill off a living language).

Classicists like equally to brag and complain that they have to learn a lot of languages. Most American PhD programs require exams in Ancient Greek, Latin, German, and either French or Italian: if you know either French or Italian, the thinking goes, you can fake your way through the other.

These languages are the tools of the trade, but they are also metonyms for the philological traditions that we are expected to put on a convincing show of knowing—with, say, the occasional name-check of Wilamowitz. Once you decide to get serious about the field, you learn to take these traditions for granted as the most inherently valuable. The history of European classical scholarship is entangled with the esteem that Greek and Latin have enjoyed in countries where German, French, Italian, or English is spoken. Many scholars who identify with the European classical tradition assume that any scholarship worth reading, or at least citing, will be in one of those four languages.

On the one hand, the modern language requirements of Classics PhD programs should really start to reflect that interesting and important things have been said and are being said about Greco-Roman antiquity in countless languages other than English, German, French, and Italian (why not accept Turkish or Arabic or Chinese—isn’t, after all, scholarship really just a form of “reception”?). On the other, the absence of Modern Greek from the list of discipline-approved languages is itself curious, and stranger still if you consider how classicists love to spend time, and to talk about spending time, in Greece.

Like fourteen European countries and two other former British colonies (Canada and Australia), the United States has a home base for its archeologists and classicists in Athens, at the American School of Classical Studies. It should go without saying that plenty of scholarship has been and continues to be written in Greek; Greek universities often have enormous Classics departments. There is simply more information in Greek about Greek archeological sites, both at the sites and in print. And for better or for worse Greek antiquity is more urgently present in national conversations (and at bookstores and on social media) in Greece than anywhere else.

Like fourteen European countries and two other former British colonies (Canada and Australia), the United States has a home base for its archeologists and classicists in Athens, at the American School of Classical Studies. It should go without saying that plenty of scholarship has been and continues to be written in Greek; Greek universities often have enormous Classics departments. There is simply more information in Greek about Greek archeological sites, both at the sites and in print. And for better or for worse Greek antiquity is more urgently present in national conversations (and at bookstores and on social media) in Greece than anywhere else.

So why does Modern Greek still not have a seat at the classicists’ table?

This is, bluntly put, largely because our discipline continues to take a colonialist view of, among other things, Greece, Greeks, and (Modern) Greek. Historians and anthropologists who work on Greece have been much more willing than classicists to acknowledge the country’s legacy of metaphorical colonization: not by the Ottomans, but by the early European antiquaries and travelers who planted their flags in the ruins of Greek antiquity.

At a time when European powers were scrambling to expand their empires, the travelers’ influential approach to the Ottoman-held “Classical Lands” was, as historian K.E. Fleming points out, “representative of a different form of colonialism, in which the history and ideology, rather than territory, of another country” is “claimed, invaded, and annexed.” Viewed through the lens of the present, the people who undertook this more “symbolic” colonization of Greece look a great deal like early versions of classicists.

Thanks to their proprietary attitude toward antiquity, they largely discounted local knowledge and described local people as apathetic to the ancient past whose ruins they seemed to live so blithely among (see here for evidence to the contrary). This kind of thinking was in turn used to justify, among other things, the removal of antiquities from Greece to countries where, supposedly, they would be better appreciated and cared for. All of this makes for a very long and complex story—one in which Greeks were hardly passive participants.

One of the story’s many legacies is that classicists trained in the “Western” classical tradition tend to disregard Modern Greek as a scholarly language, while Greeks who want to participate in the tradition—to have their voices and ideas heard abroad— earn degrees in other countries and publish their research in English, German, or French. Granting Modern Greek a more valued place in the professional conversation would be a positive step for a field that, on the point of colonialism, has a lot to answer for.

Beyond the political argument—and on the more personal, spiritual level that Woolf evokes in her own essay—the struggle to learn Modern Greek can bring a special kind of joy to those of us who first came to the language in its ancient form. That joy is the main reason I recommend that classicists spend at least a little time on Modern Greek, and ignore the gnawing voice that will say it’s a waste of time.

In a recent blog post (“What does the Latin actually say?”), Mary Beard makes an important point: for a lot of people it is hard for people to learn dead languages because we learn them passively. “It is both the plus and the minus of Latin,” she writes, “that we never have to ask for a pizza, or the way to the swimming pool, in it.”

My own learning style is certainly more “verbal” than “logical.” I like to talk, so I make much slower progress at learning dead languages passively than at learning living languages actively (my German is bad, but I could think of no greater waste of my own time than a “German for Reading” class). Modern Greek, of course, is not Ancient Greek: the linguistic politics here are particularly delicate and complex for historical reasons. The pronunciation can be a psychological barrier, and the language has changed since antiquity: classicists are often especially surprised to learn that infinitives have long since passed out of use. Greek also brims with borrowings from Turkish, Albanian, Italian, French, English…. But so what? Classicists’ own modern language requirements count Italian and French as substitutes for each other.

There’s no denying that having to decline Greek nouns when I order a pizza, or manipulate Greek verbs when I ask the way to the swimming pool, has brought even the ancient language to life for me. After years of studying Modern Greek, I have a far better recall for vocabulary, handle on verb forms, and instinctive sense for accentuation. The time I have dedicated to Modern Greek is some of the best I have spent as a classicist, since it has given me a sounder, more internalized sense of the ancient language (a better Sprachgefühl, as a more responsible classicist might say).

It’s fun, too, to learn how meanings of words have changed over time. For years ὁφόρος was, in my mind, the tribute paid to Athens by its Delian League allies. Now the word just means “tax” (inasmuch as tax ever “just” means tax). Being αγαθός nowadays is not usually such a good thing. A στήλη can be a “column” in a newspaper (or on Eidolon). In chapter 4 of thePoetics, Aristotle observes just how much pleasure people take in learning and inferring: in looking at an image of someone and recognizing, “Oh, that’s him” (οὗτοςἐκεῖνος, 1448b). Making connections between two things—hearing a new word and realizing you already know it, just differently—sends a spark of joy through the brain. And anyway there is something to be said for a language that allows you to describe a tall, fit guy as a kouros in everyday conversation.

The twists and turns of Greek linguistic history also mean you can play specifically with avoiding Ancient Greek. Oftentimes there is a choice between describing something with a “high-register” word with ancient roots or a “low-register” vernacular or foreign word. Liver, for example, is συκώτι (derived, like Italian fegato and French foie, from a word for “fig”), but when the matter is a disease of the liver the more classicist-friendly ήπαρ is common. Speaking of liver, who would you buy it from: the κρεοπώλης or the χασάπης? The one features in beginning Ancient Greek textbooks; the other comes from Turkish. A Greek professor of Latin once told me that he revels in speaking English precisely because it offers similar opportunities to play with the nuance of register: between Anglo-Saxon, French and Latinate diction (to use a classic example, does Elizabeth II strike you as queenly, royal, or regal?).

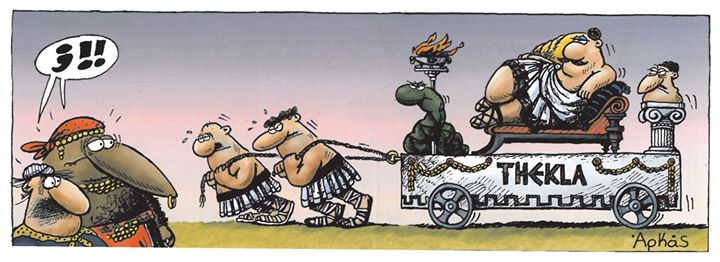

The Facebook page Ancient Memes exploits the space between these levels by captioning “high-register” artworks with dialogue in very modern, “low-register” Greek. Reading things like Ancient Memes, or my few copies of “Aristophanes in Comics,” has introduced new playfulness into my approach to Ancient Greek. And play, of course, is one of ways we learn best.

The Facebook page Ancient Memes exploits the space between these levels by captioning “high-register” artworks with dialogue in very modern, “low-register” Greek. Reading things like Ancient Memes, or my few copies of “Aristophanes in Comics,” has introduced new playfulness into my approach to Ancient Greek. And play, of course, is one of ways we learn best.

So what is still keeping many classicists (again, leaving the more political argument aside) from seizing the real practical benefits that Modern Greek has to offer: the opportunity to spend time in Greece more comfortably, the chance to collaborate with Greek colleagues more substantively, the opportunity to bolster our grasp of the language and its extremely longue durée, and to procrastinate by laughing at Ancient Memes?

When I posed a version of the question to a professor in Thessaloniki, he had a good answer. Classicists, he suggested, are easily embarrassed and afraid to make mistakes. Making mistakes is crucial for language acquisition, and sometimes the mistakes will be horribly embarrassing ones (I have, in polite conversation, said τσιμπούκι when I meant τσιμπούρι). Once, after I paid for books at a bookstore in Greece, I overheard the woman who had just rung me out ask a colleague with genuine bewilderment: “What does she want with an Ancient Greek book if she can’t even speak Greek?” In a field that already demands so much posturing, so much pretense of knowing Greek and Latin, risking mistakes and “not knowing” means risking a lot of your ego.

But it’s worth it. Learning Modern Greek, at least to the extent that I have managed to learn it, has made both my life and my relationship with my work all the richer. I haven’t even mentioned the unique pleasure that modern Greek literature offers the classicist. That sheer enjoyment aside, few people have been more influential in shaping modern views of Greek antiquity than George Seferis, or have problematized the periodization of Greek poetry more than Constantine Cavafy (translated into English most recently by critic and classicist Daniel Mendelsohn). I first came to Modern Greek after reading Seferis’ essay “Delphi” (Greek here), but since then have actually come to prefer paddling around in Greek literature’s less classical waters.

Nevertheless, since I’m teaching ancient Greek mythology again this semester, the text I’m most excited about right now is Auguste Corteau’s Νεοελληνική Μυθολογία. It is a parodic re-imagining of ancient Greek myths: on one page, Erebus makes a move on his sister Nyx: “Hush you idiot,” she replies, “Mom’ll hear and call Social Services.” Later, Kronos appears on the beach and informs his father he’s come to play paddle ball. “But I don’t see any balls,” says Ouranos. “Nor will you ever again,” says Kronos.

Nevertheless, since I’m teaching ancient Greek mythology again this semester, the text I’m most excited about right now is Auguste Corteau’s Νεοελληνική Μυθολογία. It is a parodic re-imagining of ancient Greek myths: on one page, Erebus makes a move on his sister Nyx: “Hush you idiot,” she replies, “Mom’ll hear and call Social Services.” Later, Kronos appears on the beach and informs his father he’s come to play paddle ball. “But I don’t see any balls,” says Ouranos. “Nor will you ever again,” says Kronos.

Now, with the prospect of a long plane ride ahead of me, I’m looking forward to having a few quiet hours with the book—no matter how much of it I manage to understand, or how often I know when I ought to laugh.

*First published (Sep 8, 2016) in EIDOLON online journal as part of a bimonthly column, Disciplinary Action, in which Johanna Hanink addresses the politics of the Classics field.

Johanna Hanink is Associate Professor of Classics at Brown University, US. Her recent book, The Classical Debt: Greek Antiquity in an Era of Austerity (Harvard University Press 2017), explores how Western ideas of classical antiquity have created a particularly fraught relationship between the European West and Greece, especially in the context of Greece’s recent “tale of two crises.”

Read this article in Greek, translated by Konstantinos Poulis: Για την άγνοια των (νέων) Ελληνικών