“We must salute him as he rightfully deserves and shout it from the rooftops: he is one of the greatest, one of the most remarkable poets of our time”. These were the words of celebrated French author Louis Aragon to describe his impressions upon first coming across Yiannis Ritsos’ Moonlight Sonata.

Written and published in 1956, Moonlight Sonata may be read as an intense portrayal of the subject of loneliness and alienation of the uncommitted individual. The scene is set in a dark, decaying, haunted family mansion full of memories, old furniture and collected bric-a-brac, its plaster flaking off and its floorboards lifting and cracking. The former glory of this house and her failure to maintain it have become major burdens for the Woman in the Black, who is the narrator of this poem.

and as the spring breeze blows around us

perhaps we’ll even imagine that we are flying,

because, often, and now especially, I hear the sound of my own dress

like the sound of two powerful wings opening and closing,

you feel the tight mesh of your throat, your ribs, your flesh,

and when you enclose yourself within the sound of that flight

you feel the tight mesh of your throat, your birds, your flesh,

and thus constricted amid the muscles of the azure air,

amid the strong nerves of the heavens,

it makes no difference whether you go or return

it makes no difference whether you go or return

and it makes no difference that my hair has turned white

(that is not my sorrow – my sorrow is

that my heart too does not turn white).

Let me come with you.

alone to faith and to death.

I know it. I’ve tried it. It doesn’t help.

Let me come with you…

The Woman in Black, who has passed her prime, is persistently asking a younger male companion to allow her to come out with him for a walk in the night so that together they might see the city in the relentless moonlight. The silent presence of the young man is felt throughout the lady’s long confessional monologue. The Woman in Black might be an early version of Ismene or Elektra. She lives with a gnawing loneliness and is losing her battle against age and death. Yet in her acute erotic awareness of the young male visitor in the house, she prefigures the more intense eroticism of Phaedra. Trapped in her house of memories, she longs to escape the cloying house and her past and to embrace some real human connections, to embrace the present and the future. In this sense the lady in the poem represents that part of the old world, which Ritsos thinks is condemned to perish with its aristocratic past because of its aversion to adapt and participate in the process of change.

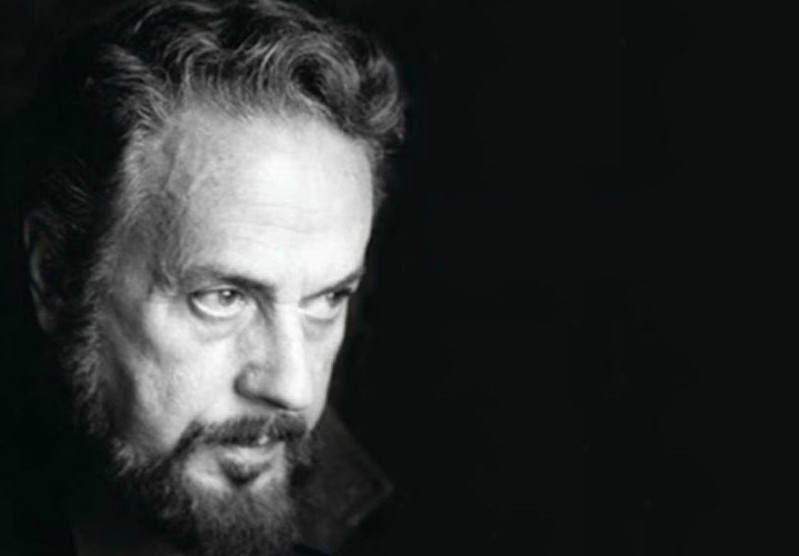

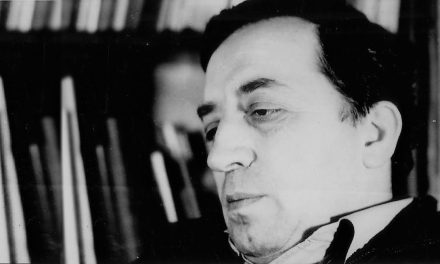

The poet

When Yiannis Ritsos passed away on November 11, 1990, the world of poetry lost one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. “Yannis Ritsos,” wrote Peter Levi in the Times Literary Supplement of the late Greek poet, “is the old-fashioned kind of great poet. His output has been enormous, his life heroic and eventful, his voice is an embodiment of national courage, his mind is tirelessly active“.

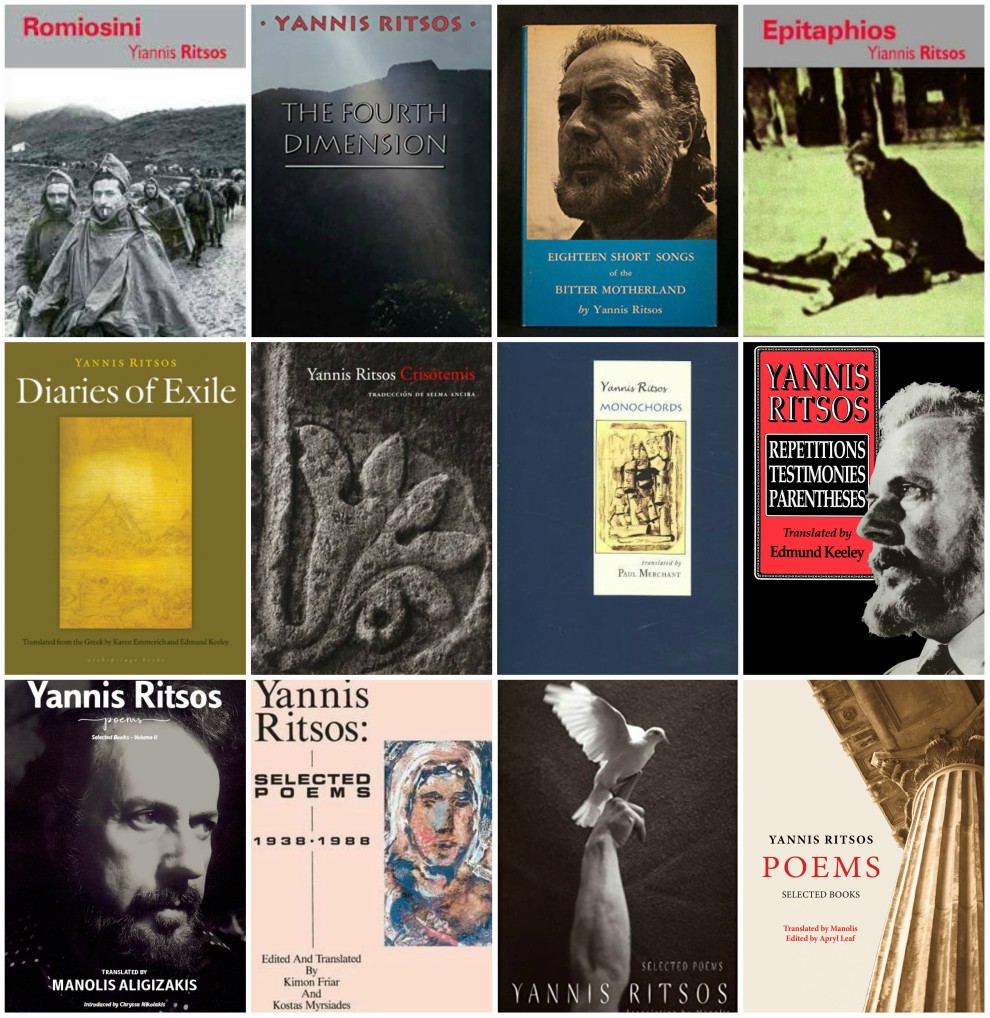

Plagued by turberculosis, family misfortunes, and repeated persecution for his Communist views, he spent many years in sanatorums, prisons, or in political exile while producing more than 100 poetry collections, 9 novels, and 4 theatrical plays. Epitaphios, Romiosini and Moonlight Sonata are three of his best-known works. In 1975 he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. When he won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1975, he was quoted as saying that “this prize is more important for me than the Nobel”. He also wrote countless articles and made numerous translations of other works.

Ritsos’ poetry ranges from the overtly political to the deeply personal, and it often utilizes characters from ancient Greek myths. At their best, Ritsos’ poems, “in their directness and with their sense of anguish, are moving, and testify to the courage of at least one human soul in conditions which few of us have faced or would have triumphed over had we faced them“, as Philip Sherrard noted in the Washington Post Book World. In long poems like his celebrated Romiosini (1947), Moonlight Sonata (1956) and most of his later volumes, Ritsos writes with compassion and hope, celebrating the life, toil, and dignity of the common man in an unadorned and direct language.

To use Pantelis Prevelakis’ words, “Without Ritsos’ eloquence, Greeks would have forgotten how to name a major part of all those things that are there before their eyes. […] Sometimes like an all-seeing sun, sometimes like a lantern-bearing thief in the night, but never devout, never a naturalist, Ritsos verily surveyed Greek space and delved deep in many of its folds”.

A.R.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE