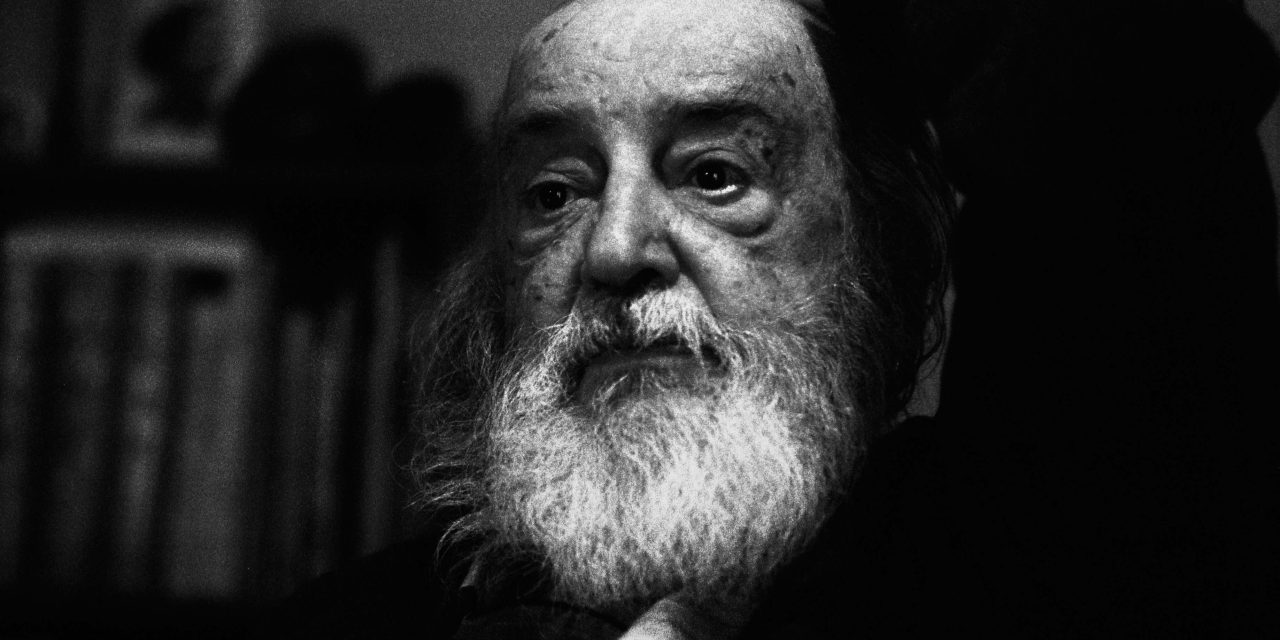

Miltos Sachtouris (1919-2005), a native of Athens, Greece, was one of the leading Greek poets of the postwar era. When he was young, he aborted his law studies to follow his real passion, poetry, and adopted the pen name Miltos Chrysanthis, under which he wrote his first poem The Music of My Islands in 1941. In 1960, he began publishing When I Talk to you and The Spectres, or Joy on the Other Street. Two years later, he received the Second State Poet Prize for The Stigmata.

He later wrote The Seal, or The Eighth Moon (1964) and The Utensil (1971) from the publishings of Keimena. During the last years of his life he worked on Colorwounds (1980), Ectoplasms (1986), Sinking (1990), Since (1996) and The Clocks Turned Upside Down (1998). He received the Grand State Literature Prize in 2003 for the entirety of his work. His work has been translated and published in several languages including English, French, German, Russian, Polish, Italian, Spanish, Dutch.

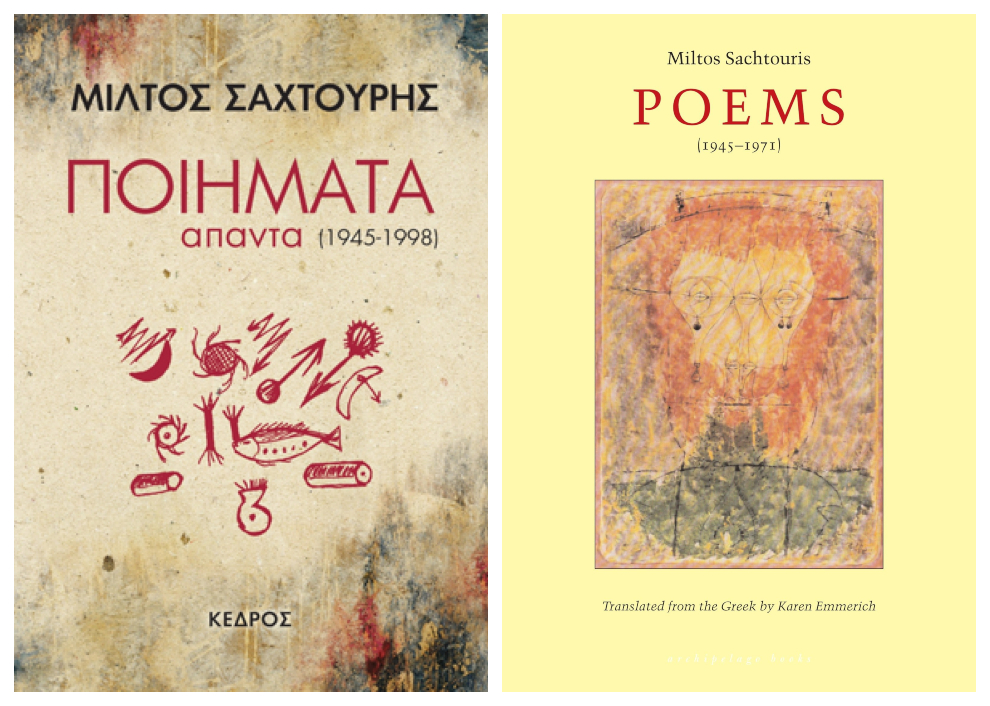

Poems (1945–1971), first published in 1978 contains work from the nine volumes Miltos Sachtouris wrote during the most productive period of his poetic career. The first of these volumes was written during the Axis occupation of Greece, and the last was published thirty years later during the military junta of 1967–74. Part poetic auto-biography, part historical document, this collection thus chronicles the writer’s reaction to three decades of intense social and political upheaval in a nation experiencing the successive horrors of occupation, civil war, and military dictatorship.

The titles of his collections (The Forgotten One 1945, Fantastic Lays 1948, When I Speak to You 1956, The Spectres or Joy in the Next Street 1958, The Stroll 1960, Stigmata 1962, The Seal or The Eighth Moon 1964, The Receptacle 1971) could be categorised in multiple ways. The first two allude to our folk poetry; the fifth and eight collections denote a predilection for surrealism by their very title; the remainder seem to move neutrally between the two margins, albeit with a latent tendency towards a modernistic point of reference.

WINTER

[Translated by Karen Emmerich]

How beautifully the flowers withered

how perfectly they withered

and this crazy man careens through the streets

with a frightened swallow’s heart

winter came and the swallows all left

the streets filled with puddles

two black clouds in the sky

lokk one another angrily in the eye

and tomorrow the rain will come out

hopeless on the streets

dispensing umbrellas

the chestnuts will be jealous

and form yellow wrinkles

the other peddlers will come out too

the man selling ancient beds

the man selling hot sheeskins

the man selling steaming salep

and the man selling boxes of snow

for the poor hearts

Evocative and deeply moving, Sachtouris’s poetry builds up, block by linguistic block, an unforgettable vision that speaks even to those who inhabit worlds different and distant from his own. As translator Karen Emmerich suggests, “Miltos Sachtouris’s rather nightmarish view of the world emerges from his response to a cruel contemporary history and his need to evoke its hidden reality“. To use Vangelis Hatzivasileiou’s words, “What Sachtouris sees in the Occupation, the Civil War and the social and political amoralism during the first couple of decades after the war is the inability of people as a collective body to prioritise certain moral values and solutions as an antidote to the crisis of the times. Nevertheless, although Sachtouris observes the same things that others of his generations also ponder on, he reaches rather different conclusions: the dead of the armed conflict and the civil strife are not unvindicated people fallen for a just cause, but tremulous heroes of an epic in which both victims and persecutors take equal part. History is not transformed into indelible memory but rather into a contemporary tragedy, which is being staged with the very same intensity to our own day“.

As Dimitris Maronitis eloquently put it, “the poet’s poetic production is characterised by a complex frugality with regard to both quantity and content; his poetry forms a system of ultimate equilibrium, which is ensured thanks to the subtle weighing of minute differences. There are no feverish, external antitheses to be found; the fever burns the poem from within, whilst the surface usually remains untroubled, just like snow, or glistens like ice […] I believe that he offered himself as a vessel of choice and expression for the post-war absurdity, and suddenly modern Greek surrealism rejected its ornamental opulence“.

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE