Kostas Karyotakis is the poet most emblematic of the turbulent interwar period in Greece. Though traditional in form, usually with end-rhyme and regular metres, Karyotakis’ poetry is modern in content, often pessimistic and bitingly satirical.

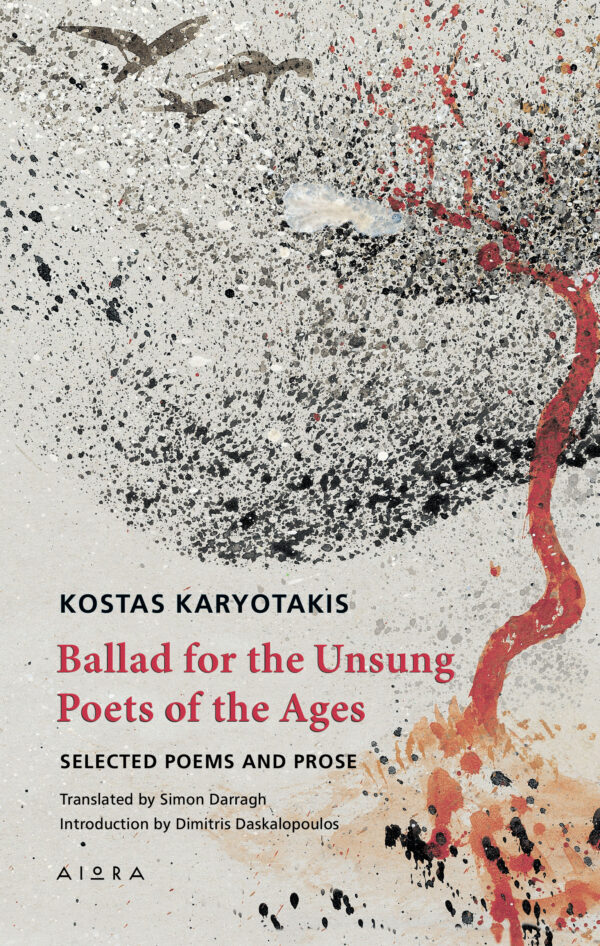

In a recently published bilingual edition titled Ballad for the Unsung Poets of the Ages (Aiora, 2024), selected poems and prose of Karyotakis are made available for English-speaking readers. Masterfully translated by Simon Darragh, they convey the main traits of his poetry, which combines reverie with sarcasm, a stifling sense of everyday reality with poignant irony. This is verse that is both piercing and resonant.

STANZA 3

You told me of your life,

of the loss of youth,

of our love which laments

its own death,

and, as a flashing tear

passed in your eyes,

a cheerful sun

broke through the window.

In the introduction to the book, Greek poet Dimitris Daskalopoulos notes that Karyotakis’ poems “encompass realism and symbolism, and also show the influences of chiefly French poets, such as Jean Moréas, Charles Baudelaire and José Maria Hérédia”. His poetry has as its main themes erotic love and death, and is “imbued with a pronounced air of pessimism and a manifest painful suffering arising from a life lacking fulfilment”. At the same time, contrary to scholars’ early beliefs that the Generation of the 30s viewed Karyotakis adversarially, there are clear reverberations of the Karyotakis strain in several emblematic poets of the 30s, while his influence has been marked among later poets, including those of our times.

The tragic end of his life was very much talked about by young people at the time and a trend emerged of morbid versifying and literary emulation going by the name of ‘karyotakismos’ but it disappeared after a while without leaving any significant literary work. The important thing is that Karyotakis’ suicide brought this rather neglected poet to the limelight, promoting him as someone who stood out in the era’s mediocre poetic production. It also set a hallmark of sincerity and authenticity on his output. “His personal misfortunes, the fixation with death in many of his verses, and the marked satirical of his poems, which occasionally turns into self-deprecation, managed to transform his individual drama into ‘an active metaphor of human destiny’”.

STANZA 2

Free from all, I want

to float on the world’s chaos.

If I still had a friend,

let him leave, let him pass.

And when death asks for

the riches I have amassed,

you, my boundless bitterness,

you will be all I have to show.

Karyotakis was for a long period undervalued and misconstrued. The reception and wider recognition of his poetry stands typically as a case of belated reaction and faulty aesthetic appreciation. A substantial reassessment of his work arose in the 1960s, when a two-volume literary edition edited by G.P. Savvidis was published as Apanda ta Evriskomena [Collected Works]. This was followed by several extensive papers and articles in periodicals about his life and work. Since then an ever-expanding literature has yielded an extensive chronology of his life and times, a tabulated glossary culled from his poems, a draft bibliography and scholarly congresses regarding his overall output, according him his rightful place in twentieth-century Greek poetry.

In the words of Daskalopoulos, the poetry of Karyotakis “signalled the end of this traditional poetic expression, prior to the emergence of modernism – though it did not in itself mark the arrival of modernist poetry in Greece”. Thus Karyotakis “holds a special position between tradition and free verse, and remains an active force in contemporary poetry”.

A.R.

*Simon Darragh was a poet and translator. He translated among other things the works of Nikos Kavvadias. Foreign Correspondence (Peterloo, 2000) is a volume of Darragh’s own poetry. Darragh was a Hawthornden Fellow, and a Translator in Residence at the University of East Anglia. He lived in the Northern Sporades for 25 years. He died in 2023.